ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF EXCESSIVE DEER POPULATIONS

advertisement

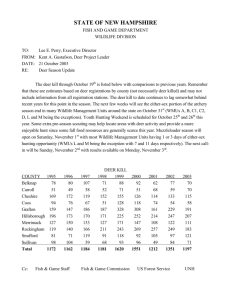

ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF EXCESSIVE DEER POPULATIONS Summary For many years volunteers of the North Branch Restoration Project (North Branch) have been observing the increasing impact of browsing deer. The first mention of deer in the records of the Project was when a doe was observed in Miami Woods in 1980. Populations increased slowly during the following years until about 10 or 15 years ago when negative impacts began to be observed by volunteers as some herbaceous species began to disappear and browse lines appeared on woody vegetation. Since then, the deer population has erupted and negative impacts have greatly increased. Extreme adverse impacts currently exist in Miami Woods and St Paul Woods. It appears that impacts are intensifying in other North Branch sites, but there has been no systematic assessment. In an attempt to quantify negative impacts on vegetation, a rapid assessment of impacts on woody vegetation was made during the summer of 2012 and combined with longer term observations of impacts on herbaceous vegetation. The pattern of adverse impact on ecological health with increasing abundance of deer illustrates the need for management of deer beginning at low densities. Background Browsing by white tailed deer is a natural part of healthy prairie and woodland ecosystems. It is not harmful when populations are of light density and in balance with the vegetative community. Historically, predators held deer populations in check at a density of about one per 40 acres of natural area or 16 per square mile. (Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, et. al.) Currently within the North Branch watershed densities are far in excess of that number. Studies have shown that above a density of 16 per square mile, vegetative quality begins to deteriorate together with insect and bird populations that rely upon the diminishing plant species. Currently within the North Branch watershed densities are far in excess of 16 per square mile, some sites by a multiple of 10 or more. At a “normal” level of browsing there is no negative impact on the populations of plants preferred by deer such as lilies and orchids, and those plant populations can be sustained without special protection from deer. However, as densities increase, a continuum of plant species decline in abundance and eventually disappear entirely. The assessment method discussed here is focused on five levels of adverse impact. The “no affect level” can be thought of as being the zero level at the base of the five point scale. Woody Vegetation To assess the impact of the unmanaged herd, a rapid assessment of conditions has been made by reviewing the condition of woody plants within the sites being restored by the volunteers of the North Branch Restoration Project. A checklist was developed and visits were made to all North Branch sites during the period from July 31 to August 3, 2012. The primary focus of the assessment was on the intensity of browsing on shrubs and on tree seedlings and saplings. A key indicator was the presence of a browse line along wooded edges adjacent to lawns, parking areas and paths. A second focus was on the intensity of browsing on native woody species and on common buckthorn. This provided a rough assessment based on visual impressions. Observations were made by briefly walking through the sites and taking notes. The five level classification of adverse impact on woody vegetation is summarized below. 1. No visible browse line No obvious browsing of native woodies or buckthorn. 2. No visible browse line. Native woodies lightly browsed, buckthorn not browsed. 3. Partial browse line, Native woodies heavily browsed, but some still present in edges. Buckthorn browsed, but foliage extends to the ground. 4. Browse line continuous Native woodies and buckthorn heavily browsed, but buckthorn foliage extends to the ground. 5. Line sharply defined, Native woodies & buckthorn twigs gone up to five feet. Forbs The woody assessment gives a rough picture of the relative severity of impact by deer on North Branch sites, but it does not address the question of the impact on the remainder of the vegetative communities. This is particularly the case with broad leaved plants (forbs). Deer do not eat grasses or sedges except for a brief period in early spring when the new growth of some sedges and grasses is eaten. This stops when new growth of broad leafed plants becomes available and has no obvious lasting impact on the browsed plants. Deer have a hierarchy of preferences among food plants which is generally consistent although some have individual preferences, probably learned as fawns from their mothers. The result is that as deer densities increase, preferred plant species are progressively impacted and then disappear. At very light densities deer have little obvious impact on woody species, but impact on preferred forbs begins long before browse lines appear or native woody species are negatively impacted. Therefore even if a site falls into category one based on assessment of woody species, negative impacts may be under way in the forb populations. By the time buckthorn begins to be eaten in stage three, substantial damage will have been done to the forb community. Ideally deer browse would be light enough to allow all native plants to survive in numbers sufficient to sustain their populations, i.e. plants such as orchids and lilies could survive on their own without being placed in cages. Unfortunately, this zero level of adverse impact does not exist within the Forest Preserves along the North Branch. A listing of deer preferences for broad leafed species is shown below. It is based to a large extent on observations in Miami Woods, but includes information from other sources as well. As preferred species are eliminated, pressure increases on plants in the next preference category which are reduced and then eliminated. The resilience of species within a preference category varies considerably so not all plants in a given category disappear at the same time. The five forb categories can be roughly equated to the five levels in the woody assessment. During woody category 1 the level 1 forbs are being preferentially eaten and premium plants such as orchids and lilies may disappear. As woodies reach level 2, more level 1 species will disappear and level 2 forbs will decline. As woodies reach level 3, most level 2 forbs will be gone and level 3 forbs decline. As woodies reach level 4, most level 3 forbs will be gone and level 4 forbs will decline. At woody level 5 virtually all lower level forbs will be gone, leaving only species that deer will not eat. The forb classification system is still in development and will be refined. For example there is some question as to whether Indian plantain / cacalia, sneeze weed / helenium, and clear weed / pilea belong in category 3 or 4. The plants in level five can tell a story not by their decline, but by their abundance. If deer pressure is intense, they tend to become the predominant members of the forb community. Compared to the woody categories, assessment of forb populations can provide a finer scale interpretation of impacts, but it is somewhat dependent on the availability of baseline information. If various species were not present when deer densities began to increase, the deer can not be blamed for their absence. Nonetheless, the absence of preferred species can provide valuable information. When Is Deer Management Needed In some cases evidence of very severe damage has been required before management of deer populations has been initiated. Unfortunately, this approach allows degradation of biodiversity and ecological health until low levels are reached. A key question for managers and for the public is whether it is acceptable to allow high quality habitats to degrade to some depleted level where brows lines occur and many plant species disappear before deer are effectively managed? If diversity and good ecological health are to be protected, especially in high quality areas, deer management must be initiated during the early stages of deer impact. The 2012 assessment of deer damage within North Branch restoration sites illustrates the damage occurring at all levels. A listing of deer preference as observed in North Branch Restoration Project sites follows. 1. Preferred / First to disappear Aquilegia Canadensis* Wild columbine Aster azurureus* Sky blue aster Aster Laevis* Smooth blue aster Astragalus Canadensis* Canada milk vetch Camassia scilloedes* Wild hyacinth Cypripedium candidum White lady’s slipper Dodecatheon meadia* Shooting star Baptisia leucantha* White wild indigo Baptisia leucophaea* Cream wild indigo Gentiana crinita** Fringed gentian Gentiana puberulenta** Downy gentian Habenaria leucophaea* Prairie white fringed orchid Heuchera richardsonia* Prairie alum root Hydrophyllum virginianum* Virginia waterleaf Lilium philidalphicum* Prairie lily Lilium michiganence* Turk’s cap lily Tradescantia ohioensis* Spiderwort Trillium grandiflorum* White trillium Petalostemum candidum* White prairie clover Potentilla arguta* Prairie cinquefoil Prenanthes racemosa* Glaucous white lettice Saxifraga pennsylvanica Swamp saxifrage 2. Second Preference / Second to disappear Amorpha canascens** Lead plant (new growth & flowers) Arabis laevigata* Smooth bank cress Arisaema dracontium* Green dragon Asclepias purpurascens* Purple milkweed Circium altissima* Tall thistle Circium discolor** Pasture thistle Corylus Americana* American hazel Desmodium illinoensis* Illinois tick trefoil Desmodium canadense* Showy tick trefoil Eupatorium purpureum Purple Joe Pye weed Gentiana flavida* Yellowish gentian Geranium maculatum* Wild geranium Heracleum maximum* Cow parsnip Impatiens capensis* Orange jewelweed Iodanthus pinnatifidus* Violet cress Lysimachia quadriflora* Prairie loosestrife Lobelia siphilitica* Great blue lobelia Lonicera prolifera* Yellow honeysuckle Petalostimum purpureum** Purple prairie clover Polygonatum canaliculatum* Smooth solomon seal Rhus glabra* Smooth sumac Solidago riddellii* Ridell’s goldenrod Trillium recurvatum** Prairie trillium New growth on all shrubs except Tartarian Honeysuckle & Barberry All seedlings and saplings less than five feet tall 3. Intermediate Preference / About the same as buckthorn Apocynum cannabinum Indian hemp dogbane Arisaema atrorubens* Jack in the pulpit (seedlings occur, but no flowering plants) Asclepias sullivantii** Sullivant’s milkweed Carex sp new spring growth eaten on some sedges Cornus racemosa Gray dogwood (all new growth eaten in Miami) Crataegus sp Hawthorn sp (all new growth and seedlings eaten in Miami) Helenium autumnale Sneezeweed Lespedesia capitata** Round-headed bush clover Penstamon calycosus Smooth beard tongue Rhamnus cathartica Common Buckthorn (new growth and seedlings eaten) Rosa setigera** Illinois rose Rosa blanda** Early wild rose Rudbeckia subtomentosa Sweet black-eyed susan Silphium laciniatum** Compass Plant Solidago rigida** Stiff Goldenrod Solidago ulmifolia* Elm-Leafed Goldenrod Aster novo-angliae** New England Aster Aster Sagittifolius Drumundii** Drummond’s Aster Aster Shortii* Short’s Aster 4. Next to Last Preference / Seldom Eaten Asclepias incarnate Swamp milkweed Asclepias syriaca Common milkweed Asclepias tuberosa Butterfly weed Cacalia tuberose** Indian plantain Eupatorium maculatum Spotted joe pye weed Iris virginica Blue flag Iris Mimulus ringens Monkey flower Pilea pumila Clearweed Parthenocissus quinquefolia** Virginia creeper (all leaves eaten) Potophyllum peltatum Rosa multiflora Solidago altisima Solidago graminifolia Solidago nemoralis Senecio paupericulus Vernonia fasciculate May apple Multiflora rose (new growth eaten) Tall goldenrod Grass-leaved goldenrod Old-Field Goldenrod Balsam ragwort Common ironweed 5. Virtually Never Eaten (populations favored by excessive deer browsing) Berbis thunbergii Japanese barberry Bidens frondosa Beggar’s ticks Eupatorim rugosum White snake root Hackelia virginiana Stick-seed Hypericum pyramidatum Great St Johns wort Erechtites hieraciflora Fire weed Eryngium yuccafolium Rattlesnake master (browsed early, but not impacted) Liatris aspera Prairie blazing star Liatris pychnostachya Buttton blazing star Lithospermum latifolium Broad-leaved puccoon Lonicera tatarica Tartarian honeysuckle (except fresh resprouts) Monarda fistulosa Bergamot Polygonum pensylvanicum Pennsylvania smartweed Pychnanthemum Mountain mint Seymaria macrophylla Mullen fox glove Tovara virginiana Woodland knotweed Utica procera Tall nettle Grasses (except briefly in early spring) Sedges (except early spring) *Species lost from Miami Woods since 1981, mostly during the last 10 years **Species abundance greatly reduced in Miami Woods during the last 10 years Kent Fuller, Volunteer Steward Miami Woods and Prairie North Branch Restoration Project