Introduction – Strategic Vision - University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee

advertisement

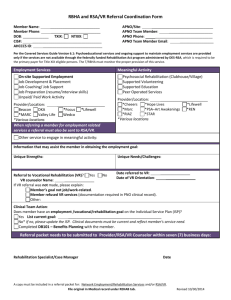

Introduction – Strategic Vision Children’s environmental health genomics-2013 New interest group in children’s environmental health genomics NIEHS supplement for pilot project to Tonellato, Laiosa, Carvan Construction of Pipeline-undergoing testing TALENS-Carvan, Heideman West end facility to stimulate conversion to specific pathogen-free facility Biobanking of zebrafish tissues has begun. Personal air pollution sensing: collaboration of Chen and Etzel IR detection of metabolism of NO, O2, etc (Hirschmugl) New programs/activities described in 2012 are activated in 2013 1. Mission The vision of the (NIEHS) is to provide global leadership for innovative research that improves public health by preventing disease and disability from our environment. (NIEHS) will require partnerships and coordinated strategies to achieve these Strategic Goals..........................NIEHS Strategic Plan The mission of the Children’s Environmental Health Sciences Core Center (CEHSCC) is to contribute powerfully to the prevention of environmentally-related diseases and disorders that affect development during the period from conception to maturation and to do so particularly among City of Milwaukee children. The Center sees itself as a regional partner with NIEHS, supporting the Institute’s national leadership aims. This section describes how Center members, assets, programs, and activities work together to achieve this mission. 2. Overall Objectives and Specific Aims Primary objective The Center will stimulate and sustain the development of the regional community of scientists that conducts significant and innovative research and community engagement in environmental health impacting children in Milwaukee and elsewhere. Working individually and in teams, scientists will conduct research along the basic, translational, clinical/public health science continuum. Their findings will move the Center toward national leadership in research on identifying and addressing environmental contributions to childhood disease. Complementary objective The CEHSCC will convert scientific understanding into effective strategies to prevent environmentally-induced childhood disease. In cooperation with partners, the community outreach arm of the CEHSCC will engage with local and regional communities effectively to understand the burden of environmentally-related childhood diseases and to act in effective ways to reduce them. The following specific aims serve as the framework to meet these objectives.1 The Center will [1] provide a rich program that attracts leading and promising scientists from diverse disciplines into a stimulating research community; [2] encourage researchers to address and collaborate on significant problems in children’s environmental health; [3] enhance investigators’ research and engagement with a wealth of resources and professional staff; and [4] offer investigators multiple options to link their expertise and knowledge with communities through outreach and engagement. 3. Children’s Environmental Health - the Challenge and Opportunity Human development, beginning with embryogenesis and continuing through adolescence, is a particularly sensitive period during which environmental factors play a pivotal role in immediate health status and lifetime health outcomes (1). Children may confront a daunting array of challenges that severely compromises their health and longevity. These include exposure to toxic contaminants, inadequate nutrition, and adverse environmental and social conditions in the home and surrounding environment (2-6). Research indicates that environmental factors contribute to birth defects, asthma, learning and behavioral deficits, and possibly, obesity (7-10). Moreover, it is increasingly clear that some adult diseases find their origin in fetal and early childhood development (11). There is strong evidence, for example, that low birth weight results from environmental exposures during gestation, predisposing infants to diseases as adults (12,13). Of particular concern are health inequities that children suffer in families with lower socio-economic status, typically, racial/ethnic minorities. For example, exposure to tobacco smoke and addictive drugs (low birth weight, stunted development); household allergens (asthma); lead (depressed learning and other neurological outcomes), etc. are all substantially higher in children born into poverty (14-18). Milwaukee mirrors the health problems and inequities that children face in urban centers across the country and is, in some respects, among the worst in the nation. Thus, City of Milwaukee infant mortality rates for all races/ethnicities, as well as for non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics in 2005-2007 and 2008-2010 were significantly higher than the comparable U.S. infant mortality rates in 2005-2007 (the most recently available data) (19a,b). Preterm birth is the major contributor (68%) to infant mortality in the U.S (19b). In Milwaukee, at least a 2-fold difference exists between zip codes in infant mortality rates (2-2.5-fold), and the prevalence of preterm birth and low birth weight (19a,c). 4. Overall Vision for the Center 1 Abbreviations: AAF, Aquatic Animal Facility; AAMFC, Aquatic Animal Models Facility Core; App, Appendix; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CDP, Career Development Program; CEHSCC, Children’s Environmental Health Sciences Core Center; CHHS, Children’s Hospital and Health System; COEC, Community Outreach and Engagement Core; CRI, Children’s Research Institute; EBAC, Exposure and Biological Analysis Core; ICO, Institutional Commitment and Organization; IHS, Institute for Health and Society; IHSFC, Integrative Health Sciences Facility Core; LSIP, Laboratory System Improvement Program; MCW, Medical College of Wisconsin; MeHg, methylmercury; MFBS Center, Marine and Freshwater Biomedical Sciences Center; MHD, Milwaukee Health Department; NBTF, Neurobehavioral Toxicology Facility; PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon; NIEHS, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; SFS, School of Freshwater Sciences (UWM); TALEN, transcription activator-like effector nuclease; UWM, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; WSLH, Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene; ZSPH, Zilber School of Public Health 4.1. Background The NIEHS Children’s Environmental Health Sciences Core Center (CEHSCC) evolved from a predecessor NIEHS Center, the Marine and Freshwater Biomedical Sciences (MFBS) Center (1978-2008) when it formed a partnership with the Children’s Research Institute (CRI) in 2006 to support joint research and community engagement (Figure 1). The aim was to establish a powerful, cohesive program of research and community engagement involving basic, translational, public health and clinical investigators to improve the health of children in general and, particularly, in the immediate region. To realize this vision, a strategic inter-institutional partnership was established between the University of NIEHS CHHS Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) and the CRI of Children’s MFBS Center CRI UWM MCW 1978-2008 Hospital and Health System (CHHS) and the Medical College 2006 of Wisconsin (MCW) (Figure 1). As the CEHSCC commenced in 2009, UWM and its partner institutions were CHHS MFBS CRI UWM Center about to experience significant expansion of their academic MCW programs and faculty. With the Center’s formative support, UWM has inaugurated two new schools, the Zilber School of Public Health (ZSPH) and the School of Freshwater Sciences CHHS NIEHS Children ’s UWM EHSC Center (SFS) that play important roles in the alliance. Soon, a thriving MCW 2009 research community emerged as the Center became the U WM Zilber Sc hool MCW CTSI of Public H ealth organizational hub for regional investigators who are engaged C R I U nex plained Infant D eath U WM Sc hool of in children’s environmental health studies. Center Fres hwater NIEHS 4.2. Moving forward The Center’s vision is to Sc ienc es Children’s Other U niv er s ities EHSC Center accelerate the development of the regional children’s Milw auk ee 2012 H ealth D ept. environmental health community into a system of resources, Laboratory of H y giene interactions, and collaborations that addresses key Figure 1. Evolution of the CEHSCC environmental health problems, developing in and/or emerging during childhood. The Center’s deliberate will continue to encourage individual and multi-disciplinary teams of scientists to work on the vexing health problems of children living in adverse environments. Its distributive and diverse institutional and scientific foundation makes possible the Center’s broad portfolio of research, extending from basic to human studies and promotes many opportunities in the realm of community engagement. To illustrate, the UWM School of Freshwater Science (SFS) brings together environmental and environmental health scientists to address issues of freshwater and children’s health. Zilber School of Public Health (ZSPH) scientists provide robust translational expertise in the sphere of children’s population health, epidemiology, and health inequities. CRI and MCW researchers offer access and depth in pediatric medicine. To serve the public, Center members’ collective scientific knowledge needs to reach the Milwaukee regional community and beyond. Thus, the CEHSCC is committed to engaging with ethnic communities and related governmental bodies and officials, teachers and students, and health professionals in order to improve children’s environmental health understanding and outcomes. The process begins with a career development model that emphasizes community engagement as an integral part of the professional life of scientists and links this with the programs of the Center’s Community Outreach and Engagement Core (COEC). 5. Overview of Research Base The CEHSCC considers its basic mission to advance and sustain a regional Figure 2. Regional Full Membership and Disciplinary Expertise community of scientists that strongly contributes to children’s environmental UWM (23)1 behavioral, developmental, and reproductive biology, health research and engagement. Science bioinformatics, biochemistry, biophysics, endocrinology, microbiology, neuroscience, public health nursing, public health policy and law, physics, thrives on the combination of long-term, toxicology focused research and inquiries into new MCW (25) biostatistics, cell biology, genetics, molecular biology, areas and questions. The Center facilitates pathology, pediatrics, physiology, toxicology depth and novelty by supporting a research UW-Madison (4) molecular genetics, nutrition, toxicology community that attracts investigators from Marquette U (3) biology, biomedical science, microbiology Concordia U (3) analytical chemistry, biophysical chemistry, toxicology various institutions and many backgrounds. MKE Health Dept. (1) environmental health, microbiology Figure 2 summarizes the breadth of organizations and disciplines represented in 1Number of members. Membership list in Table 1 (NIEHS Table B) of the Center’s membership. Included are Administrative Core, section 4. three major and one local university, a nationally recognized medical school, a first rank Children’s Hospital, and the Milwaukee Health Department. With the participation of scientists from the ZSPH and SFS at UWM and key units within MCW/Children’s Hospital (CRI and Unexplained Infant Death Center [UIDC]) etc., members with many backgrounds come together in a unique inter-institutional research community (Figure 2). The resulting concentration of expertise provides the capacity and opportunity to form diverse research teams and the flexibility to find new collaborators as interests evolve. Section 7 summarizes the blend of deepening research, novel initiatives, and new and established collaborations that is occurring within the CEHSCC community. 6. Introduction to Research Portfolio and Environmental Health Identity The Center’s environmental health identity stems from the wealth of multi-disciplinary expertise that is gathered into three major areas of research in children’s environmental health and extending along the translational pathway from basic to children’s research (Figure 3). At the level of “Pathways of Toxicity,” interests coalesce around gene-environment Communities interactions and other basic mechanisms of toxicity, the zebrafish model organism as a key tool for studying developmental toxicity, and the generation of novel methods that support toxicological study. In the area Children Children Children’s Health of “Developmental Toxicology,” scientists seek to & Inequities understand organ-based toxicity, including Lab Animals Lab Animals neurobehavioral toxicity and pathology that originates Pathways Developmental in waterborne exposures. Finally, “Children’s Health of Toxicology Toxicity and Inequities” research seeks (1) to understand the underlying etiology of children’s health inequities in the urban environment, particularly the city of Milwaukee Cells & tissues Cells & tissues and (2) to contribute formatively to the emerging area Biomolecules of children’s environmental genomics, and the understanding of the epigenetic origins of childhood Figure 3. Major themes of the Center’s Research Portfolio and adult diseases. Impact of research on environmental health The Center’s long-term research objective is to favorably impact children’s health. To approach this goal in the near- and mid-term, the Center will support strong, innovative research projects and encourage the formation of scientific teams that connect basic and translational researchers. In order for this strategy to deliver changes in children’s health, two additional tactics must be implemented. First, high impact research that is potentially high risk needs to be encouraged. Second, collaboration with experts in community outreach and engagement and environmental health policy must be increasingly emphasized (long-term impact). 7. Center Investigator Research and Engagement Portfolio 7.1. Relationship of Research and Engagement to NIEHS Strategic Plan 2012 The Center assesses its research portfolio in part in relationship to the NIEHS Strategic Plan 2012 (www.niehs.nih.gov/about/strategicplan/). Focal areas of Center research that overlap with the Strategic Plan are listed in Figure 4. Figure 4. NIEHS Strategic Plan 2012: 7.2. Introduction to Research and Engagement Research Areas of congruence with Center research portfolio progress reports by Center investigators are gathered in Appendix (App) 1. Some of the strengths and highlights of research progress Fundamental Science: child development, and/or plans for future research by Center members are described life-span analysis, model organisms, geneenvironment interactions, high throughput below by focal area of collective strength as illustrated in Figure 3. methods In toto, the summaries portray the environmental health identity of Exposure Science: new tools and the CEHSCC and its impact on children’s environmental health. technologies, analytical measurements, Where possible, results across the translational research-community sensors, linkage with ”omics” technologies Translational Science: bench to bedside engagement continuum are included. The role of Center support in and community, public health policy and advancing research and engagement is woven into the narrative. practice, gene-environment interactions in 7.3. Pathways of Toxicity Zebrafish model organism medicine (Fundamental, Exposure, and Translational Science, Figure 4) Health Disparities: vulnerable populations Model organisms provide opportunities to study living systems. and interaction of chemicals, infectious agents, nutritional factors, and social Mammals play key roles. The zebrafish is an excellent, stressors in communities complementary model for discovering pathways of vertebrate Knowledge Management: bioinformatics, developmental toxicity, screening (mixtures of) chemicals, and computational tools, data integration probing the impact of non-chemical environmental stressors. Its attributes of rapid external development, large numbers of optically clear embryos, and facile genomics argue for a central role in understanding gene-environment interactions that lead to disease in children. In the 1990s the Center made a long-term, high risk commitment to advance the zebrafish model toward acceptance as a regulatory model organism. Center members R. Peterson and W. Heideman were among the first to utilize the favorable characteristics of this model organism for developmental toxicological studies (20, 21). Working with J. Postelthwaite, M. Carvan and P. Tonellato constructed the first annotated genomic maps comparing zebrafish, rat, and human chromosomal DNA sequences and demonstrated their striking gene and syntenic similarities (22). D. Weber assembled powerful technology to study life-stage dependent behavior of zebrafish in the Center’s Neurobehavioral Toxicology Facility (Aquatic Animal Models Facility Core, AAMFC, 4.5) (23,24). H. Tomasiewicz and K. Kosteretz developed procedures to obtain the superb embryo survival rates needed to support quantitative studies. In 2013, the Center assembled new resources that advance the zebrafish as a prime toxicological model, including specific pathogen-free fish (AAMFC, 3.4) and transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN) gene-disruption methodology (AAMFC, 5.5.1). A bioinformatics pipeline for nextgeneration genome and transcriptome sequencing (Integrative Health Sciences Facility Core (IHSFC, 9.2.5) and routine biobanking of zebrafish tissues (Exposure and Biological Analysis Core, EBAC, 4). have been instituted. Together, they stimulate research, particularly linking environmental health with genomics. Gene-environment Interactions (Fundamental and Translational Science, Knowledge Management) The premise that health outcomes derive from gene-environment interactions underlies a significant segment of members’ research. For example, across the translational path, beginning with basic research, W. Heideman (genetics) and R. Peterson (toxicology) study TCDD as a developmental toxin (App1: 1.1.3,1.1.4). Having demonstrated the extensive similarity between the gene regulatory Ah receptor system in mammals and zebrafish as well as the disruption of cranial-facial and cardiac development in zebrafish by TCDD, they have shown that there is an epigenetic component to its effects and are investigating its mechanism (25, 26). To facilitate epigenomic/transcriptomic research in zebrafish, Dr. Tonellato, Director, Bioinformatics Subunit, IHFSC, has built the first workflow computational system for Next Generation Sequencing data analysis (App1: 1.2.9). Several investigators are testing the system with pilot project funding. Methylmercury (MeHg) is a potent neurotoxin that presents itself to the fetus through maternal consumption of fish (27). M. Carvan, D. Weber, P. Tonellato, and co-investigators J. Dellinger, A. Udvadia, and D. Petering have undertaken a far-reaching study of its effects on the neurobehavioral development of the zebrafish (23,28). This medium-to-high risk (not used consistently below) project has been supported by a pilot project and the AAMFC, EBAC, and IHSFC Cores (see abbreviations and 8.4.5). After exposing fish to nM MeHg for brief periods during development, adverse effects on visual startle responses were identified in adults (App1: 2.1.24). The results were explained by a MeHg-dependent increase in threshold activity levels of retinal bipolar cells. Notably, dietary Se antagonizes this effect of MeHg (23,28). Subsequent generations not exposed to MeHg retain similar behavioral and physiological deficits, revealing a serious epigenetic impact (App1: 2.1.24). This is a highly provocative finding with major public health implication because many, if not the majority, of fetuses are exposed to MeHg. The bio-chemical basis for these outcomes is being examined: Carvan and Tonellato are conducting a detailed inquiry into the perturbations that MeHg causes within the genome and transcriptome following exposure of larval zebrafish. Moreover, Carvan and D. Petering have determined the organ distribution of MeHg (App1: 1.2.5), using special methods offered through the EBAC. Hg concentrates in the eye. Future studies will use EBAC laser dissection to isolate segments of the eye for proteomic analysis of binding sites of Hg and (epi)genomic/transcriptomic outcomes of MeHg exposure. An inter-institutional partnership between N. Tabatabai and D. Petering demonstrated at the chemical level how cadmium (Cd2+) causes a component of human kidney failure, urinary glucosuria (App1: 1.1.12). Cd2+ down-regulates sodium-dependent transporter (SGLT) protein synthesis by inhibiting transcription of their mRNA sequences (29). This process is disrupted when Cd2+ displaces Zn2+ from a key transcription factor, Zn3-Sp1, that ordinarily binds to the sglt gene promoters (29,30). EBAC (P. North, MD, collaborator) provided elegant immunocytochemical support for the intracellular location and quantification of SGLT transporters. NEW The field of personalized medicine has emerged as a novel approach to individualize and improve the diagnosis and treatment of patients through the use of genetic data. Under the leadership of Dr. P. North, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin is the first pediatric hospital in the country to routinely genotype all patients for 15 common conditions. Generally, current strategies focus on the use of genetic information. But this approach has not been successful in linking genetic variation to common diseases (31-33). Other factors need to be integrated with genetic information; in particular, patient environmental context. Thus, the Center has established a new high risk initiative supported by EBAC (P. North, genomics), IHSFC (P. Tonellato, bioinformatics), and AAMFC (zebrafish model) to integrate environmental health discoveries with pediatric genomics, based upon the gene-environment paradigm. Members, who constitute the Translational GeneEnvironment research interest group, include A. Pelech who focuses on the genetic and environmental etiology of cardiac birth defects (App1: 3.17), R. Lane, newly appointed Chair of Pediatrics who studies the epigenetics of fetal growth restriction (App1: 1.1.10), C. Bradfield with interests in transcriptomic signatures of children’s diseases (App1: 1.1.1), MCW, H. Jacob, Director of the Human and Molecular Genetics Center and a leader in individualized pediatric genomics, MCW (App1: 1.1.9), M. Carvan, who studies gene-environment interactions in zebrafish (App1:2.1.2) along with Drs. North and Tonellato, and M. Laiosa, conducting a comparative mouse-zebrafish study of the genetic impact of MeHg (App1: 1.--). The effort will leverage the research expertise and tools of these investigators. For example, a major resource is the Cardiac Birth Defect Registry, founded by Center member, Dr. A. Pelech. The Registry is unusual in that it contains 2000 medical records with extensive data about environmental conditions of children with heart defects and their blood samples available for genetic analysis, and (34). In the engagement arena, Center members have engaged with Hmong, Native American, and African American communities during the past decade to communicate the risks of fish consumption in relation to exposure to MeHg and polychlorinated biphenyls (35,36). Recently, J. Hewitt, R. Hutz, and M. Carvan developed and tested a new approach to such risk analysis in the local African American community (37). Reciprocally, the research focus within the Center on MeHg developed in part because of the concern within Hmong and Native American communities about the safety of fish contaminated by MeHg. Exposure Methods Research (Exposure Science, Knowledge Management) Center investigators are devising methods to measure exposure and outcomes of exposure to environmental chemicals. For example, there is wide ranging need to define molecular binding sites of metals and metalloids: M. Carvan and D. Lobner study Hg (23, 38); C. Myers, Cr (39); N. Tabatabai and Petering, Cd (29, 30); D. Weber, Pb (40), and Ramchandran, As (App: 1.1.11). In response, D. Petering has undertaken high risk, innovative research to develop methods that define the localization of toxic metals and metalloids in zebrafish and their protein targets in cells and tissues (toxico-metalloproteome) (App1: 1.2.5). Using a new gel electrophoresis method that maintains relatively native protein structure and provides excellent protein band resolution, the distribution of toxic metals and metalloids among proteins can, in principle, be defined by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (EBAC) and relevant proteins identified by mass spectrometry (41). NEW J. Chen, M. Gajdardziska-Josifovska,C. Hirschmugl, and M. Weinert are engineers and physicists who are designing next generation nano-sensors that selectively measure gaseous pollutants with high sensitivity (App1:1.2.2) (42). A key finding is that two-dimensional graphene (carbon) surfaces have favorable properties to serve as such sensors (43). Research has extended their range to the aqueous phase and water soluble pollutants. This is high risk research because of the difficulty in producing practical sensors. By joining the Center, these scientists will find partners across the translational path, such as R. Etzel, who provide complementary research expertise needed for their work. Once developed, such devices will greatly advance the capability to measure air pollutant and other ambient exposures of children (IHSFC, EBAC). 7.4. Developmental Toxicology The Center’s research portfolio emphasizes understanding the impact of chemicals on embryonic and early development (Figure 3). Commonly, these studies are reversetranslational, starting with diseases and disorders in infants and children that are hypothesized to involve environmental exposures and then testing the strength of such relationships in model systems. Neurotoxicology (Fundamental and Translational Science) Several researchers provide the Center with a robust base of research on the development of the zebrafish nervous system. J. Gutzman studies the control of brain morphogenesis (start-up support). Abnormalities resulting from abnormal brain morphogenesis include neural tube defects and mental health disorders such as autism and schizophrenia. This research provides the basis for investigating environmental contributors to these problems. Zebrafish have been used by several scientists to investigate if embryonic exposure to chemicals results in adult neurological deficits (Carvan, Svoboda, Weber). To illustrate with Pb 2+, a metallic contaminant of great consequence for children, , D. Weber has used new high-speed videography capability in the AAMFC to demonstrate that developmental exposure to 10 nM (2 ppb) Pb2+ (2-24 h post fertilization) results in a deranged startle response in adulthood without compromising long-term survival (App1: 2.1.22) (40). Dr. Weber has also partnered with R. Tanguay (Oregon State University) on an inter-center pilot project funded by the CEHSCC, to characterize the neurobehavioral toxicology of bisphenol A (BPA), a constituent of many plastics and, therefore, a contaminant of processed food and water (App1: 2.1.21). Embryonic exposure to nM BPA resulted in larval behavioral dysfunction and subsequent pronounced learning deficits in adults (44). As with other agents, early exposure that does not compromise overt development causes subtle neurological injury that persists into adulthood (AAMFC support). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are anti-depressant drugs designed to inhibit serotonin reuptake, thereby influencing signaling mechanisms within the brain. Low levels of such compounds have been found in the freshwater environment and in drinking water systems. In the work of R. Klaper, supported by the Director’s Opportunity Fund and the AAMFC, exposure to the SSRI fluoxetine causes fathead minnows to become aggressive at the beginning of exposure (App1: 2.1.8) (45). During chronic exposure, behavior changes to obsessive, e.g. nest cleaning, quantitatively increases. Parallel transcriptomic changes in genes involved in neurogenesis and plasticity are observed. These high profile results sustain the concern that pharmaceuticals in freshwater may exert toxic effects on the community’s health, especially children. A. Kalkbrenner is an environmental health epidemiologist who recently joined the ZSPH. She extends the neurotoxicology theme to the level of children with her studies aimed at testing potential connections between air pollution (outdoor and passive smoking) and the development of behavioral problems in children, including the on-set of autism spectrum diseases (App1: 2.1.5-2.1.7) (46). Neurotoxicological research has been abundantly translated to communities. COEC’s key participation in the Milwaukee Community’s Cleaner Valley Coalition (J. Hewitt and K. Bartholomew) provided the scientific voice about Hg toxicity that helped to convince WE Energies to convert its downtown coal-burning power plant to natural gas. Recently, the coalition received a major award for its success (COEC, 4.4). Research has also been translated into experiment modules implemented by high school students in COEC’s pre-college education program (COEC, 5.2) (47, 48). M. Carvan, K. Svoboda, D. Petering, H. Tomasiewicz, and D. Weber have contributed to this engagement program. Notably, the stimulus for Dr. Weber’s research on the behavioral toxicology of Pb was COEC’s feed-back from the community about the large numbers of children with elevated blood Pb concentrations. In turn, some of his work has inspired student experiments. Embryonic Toxicity-Neural Crest Developmental Outcomes (Fundamental and Translational Science) During development, the neural crest provides progenitor cells for a variety of tissues. Several Center members have focused their research on understanding how genes, environmental chemicals, and nutritional factors combine to cause developmental deficits related to neural crest cell differentiation in zebrafish and other model organisms. Unexpectedly, K. Svoboda and V. Lee, an expert in neural crest development, have shown in a high risk pilot project involving zebrafish and mouse models that nicotine exposure targets neural crest cell differentiation, leading to abnormal cranial-facial development (AAMFC, EBAC) (App1: 2.2.2). This is highly significant research that supports a prominent role of nicotine in birth defects. S. Smith and M. Carvan jointly use zebrafish and chick models to understand the genomic-ethanol interactions that disrupt neural crest differentiation (AAMFC, EBAC) (App1: 2.2.1). Dr. Smith has also discovered a strong nutritional synergy in a rat model between ethanol exposure and iron-deficiency in the mother during gestation and outcomes of altered neuro-behavior including learning (49). Research in this area moves into community engagement through the Center’s pre-college education program and its emphasis on zebrafish as a model for fetal alcohol syndrome (COEC, 5.2) (47). Similarly, other research by K. Svoboda undergirds the pre-college program’s focus on the embryo toxicity of nicotine. Cardiovascular Toxicology (Fundamental, Translational Science) Cardiac abnormalities constitute the major cause of spontaneous abortion during pregnancy and birth defects. Dr. A. Pelech, a surgeon who operates on infants with cardiac birth defects, has established the Wisconsin Cardiac Birth Registry and leads an on-going effort to probe whether environmental chemicals are a cause of abnormal cardiac development (34, 50). Recently, J. McGraw and A. Pelech were awarded a pilot project to probe the relationship between polybrominated diphenyl ethers, nutritional factors and such birth anomalies, using biological samples from infants born with hyperplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) (App1: 2.3.3). They have discovered high levels of a PBDE metabolite correlates with this cardiac birth defect. With IHSFC support, G. McCarver has completed an important prospective study (high impact) of infants born with cardiac defects. Intrauterine exposure to 14 volatile organic compounds and 4 halogenated hydrocarbons was determined by measuring their concentrations in offspring meconium (App1: 2.3.2). Exposure to high levels of two trichoroethylene (TCE) metabolites (trichloroacetic acid and/or dichloroacetic acid) were associated with a 3-4 fold increase in the risk of particular cardiac defects. In addition, high level exposure to these TCE metabolites was linked with an increase of congenital heart disease among children of mothers with at least one copy of ADH1C*2, a genetic variant that influences how efficiently these metabolites are produced. Lung Toxicology (Fundamental, Translational Science) Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a debilitating lung disease that develops in 20-25% of very low birth-weight infants (birth-weight < 1500 grams), remains the major cause of pulmonary morbidity and mortality in infancy. The Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) signaling pathway plays critical roles in regulating protective pulmonary responses against environmental toxicants, oxidative stress and bacterial-derived toxins. V. Sampath and R. Hines hypothesized that functional genetic variation in the TLR signaling pathway genes would modulate susceptibility or severity of BPD in premature infants (App1: 2.4.4). Their clinical study, supported by a Center pilot project, demonstrated that polymorphisms in the TLR pathway correlated with the incidence of BPD (51). These results supported the hypothesis that TLR pathway genetic variants modulate vulnerability to environmental lung injury in premature infants. Sampath is now addressing the hypothesis that environmental suppression of the immune system by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contributes to bacterial pathogenesis in newborn infants (App1: 2.6.5). Freshwater Toxicology (Fundamental, Translational, Health Disparities Science) The CEHSCC has its roots in the NIEHS MFBS Center and continues to emphasize toxicological issues related to freshwater toxic exposures (Figure 1). Both D. Lobner and T. Miller study neurotoxins synthesized by algae that are becoming prevalent in lakes due to climate change. Dr. Lobner has determined that β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), a non-protein amino acid that causes human neurodegenerative disease, acts synergistically with MeHg to damage fetal mouse neurons (App1: 2.1.14). It appears to do so by depleting cellular glutathione and, thereby, stimulating oxidative stress (52). Miller, recently funded by NIEHS and supported with Director’s Funds, seeks to establish whether toxins such as BMAA bioaccumulate in edible fish (App1: 2.7.13). He has partnered with M. Carvan and K. Svoboda to measure the neurotoxicity of algal toxins in zebrafish (AAMFC). These studies are significant because of increasing algal blooms and the potential for exposure of children. M. Gorelick and S. McLellan have conducted an important study (high impact) of the built environment to understand the relationship between admittances of children to Children’s Hospital with acute gastroenteritis and the water distribution system in Milwaukee (Pilot Project, App1: 2.7.12) (53). Spikes follow heavy rain events. Using McLellan’s expertise in finger printing pathogenic bacteria, it appears that inflow into the compromised water delivery system stimulated by heavy rains contaminates the drinking water, leading to illness. Such results raise the possibility that during these and perhaps less severe events, children and others are exposed to elevated concentrations of chemical pollutants as well as microorganisms (IHSFC, AAMFC). This research became the basis for a State of Wisconsin study of the potential human health consequences of increased storms due to climate change (App1: 2.7.3, 2.7.10). Dr. McLellan’s work also stimulated a highly original analysis of the impact of the Gulf of Mexico oil spill on beach microbial integrity (AAMFC, IHSFC) (App1: 2.7.11) (54). Dr. Hewitt sits on the External Advisory Board for the University of Texas Medical Branch’s work that provides follow-up with Vietnamese and Houma Nation fishers affected by the spill. 7.6. Children’s Health and Health Inequities NEW Children’s Health Inequities Research (Translational and Health Disparities Science) Introduction Children in Milwaukee face disease, disorders, even death among African American infants at rates worse than those seen in many developing nations (19d). The Milwaukee community, starting with the Mayor, has urgently called for action to reduce the health inequities suffered by its children. The CEHSCC has the responsibility to assume scientific leadership in addressing this dismal situation. It has made a long term commitment to support and integrate environmental and social epidemiologic research and community engagement to resolve these issues. A coalition of Center investigators has initiated community-based, epidemiologic research to understand the environmental-social basis of these health inequities in Milwaukee. Two new Center members play leading roles in environmental health equity research during the next grant period. Ruth Etzel, a world leader in children’s environmental health, brings a record of distinguished research-development of cotinine as the prime biomarker of exposure to cigarette smoke; recognition (and removal) of volatile mercury in indoor house paint; first in-depth investigation of Native Alaskan health and disease, their underlying determinants, and more (55-57). In the spring of 2013, she began an environmental epidemiological study of apparent life threatening events among children in the city of Milwaukee supported by Center start-up funds (App1: 3.3). Included in this study is a focus on new biomarkers of lung injury in relation to infant death. Dr. Etzel’s arrival has stimulated a new collaboration with the Milwaukee Health Dept. in which she and Raymond Hoffmann (MCW) will work with Eric Gass, Research Director, MHD, D. Petering and D. Weber, experts in metal/lead toxicology, to design an analysis of the Health Department’s extensive records to test the hypothesis that childhood Pb exposure adversely affects later teen pregnancy outcomes in the City of Milwaukee (58). Lorraine Malcoe also has a distinguished record of research addressing both environmental and social determinants of health. Dr. Malcoe is well known for her superfund-related research into Pb poisoning among Native American children in Oklahoma (59). She and A. Kalkbrenner are conducting an analysis of linked environmental (air pollution)-social determinants of children’s health in Milwaukee (pilot project) (App1: 3.8). Other research Dr. P. North has organized the Unexplained Infant Death Center (UIDC) in the Children’s Research Institute (Appendix 2). Beginning its second year, the UIDC researchers investigate the underlying causes of the epidemic of infant deaths in Milwaukee. Other Center investigators focus on air pollution and mortality and morbidity in children. J. Hewitt has undertaken an epidemiological study in Milwaukee County that assesses the contribution of air pollution and traffic on risk of preterm and low birth weight, leading factors in infant mortality among African American infants (App1: 3.6) (IHSFC). In a related study evolving from a pilot project, V. Sampath, MD, has begun to test his hypothesis that exposure to PAHs leads to the development of bronchodysplasia in infants (App1: 2.4.4). J. Meurer and R. Hoffmann have played major roles in defining the environmental health status of Milwaukee children, particularly their rates of asthma and environmental conditions within the home that promotes the disease (60). At a more general level, A. Kalkbrenner examines the linkages between exposure to cigarette smoke or air pollution and neurobehavioral outcomes in children (App1: 2.1.5-2.1.7) and has just received a pilot project to include Milwaukee children in her studies (App1: 3.8). Addressing other aspects of the local environment, S. Johnson, with the support of the IHSFC and Biostatistics Division Director, R. Hoffmann, has undertaken a community-based participatory research pilot project to understand the hazards associated with growing vegetables in soil contaminated with lead and other toxic chemicals, a common activity within the city of Milwaukee (App1:3.7). Her early results have been rewarded with a major grant to continue her research. In this vein, Simpson and Pelech received pilot funding to examine the geographical relationship between toxic waste sites in Milwaukee and the homes of children with cardiac birth defects (App1:3.20). Beyond the City, J. Dellinger heads a large program that focuses on the impact of the environment, including MeHg and PCBs in edible fish, on maternal-child health in Native Americans (App1: 3.1.17). Policy expert K. Bartholomew links research to improved housing (App1: 3.1). 7.7. Analysis of Research and Researchers The contents of Appendix 1 have been analyzed as shown in Figure 5. The 87 total projects strike a good balance: 33% are categorized as basic research; 38% translational science; and 29% as public health or clinical studies. Importantly, the number of multi-investigator projects approximates those involving single investigators along the entire translational path. Equally significant, many multi-investigator projects involve scientists at different institutions-64% of the basic studies, and close to 50% of the rest. The CEHSCC emerged from a MFBS Center. Thus, it was not surprising that many projects utilized zebrafish [33]. Nevertheless, it is important for the Center’s development that many projects also utilize mammalian model systems [22]. Significantly, supporting the Center goal to involve physician-scientists in children’s environmental health research, 16 physician-scientists contribute to 24 projects, 28% of the total, and are well represented in multiinvestigator and inter-institutional research. 7.8. Community Outreach and Engagement The CEHSCC is committed to a model of scientific inquiry that values relevant engagement with local communities. The COEC Director leads a coordinated effort throughout the Center to communicate with three broad groups-ethnic communities, governmental and business officials, and science educators and health professionals. COEC has established important programs for each of the groups. These include (1) durable partnerships in African American and Hispanic communities focused on local needs expressed in a 2009 Town Hall meeting with NIEHS officials; (2) initiatives with community governmental and business representatives to improve health outcomes, and (3) a premier, NIEHS-funded program for high school teachers and students, linking biology and children’s environmental health and (4) an inter-center collaboration with the Harvard University COEC to educate health professionals about environmental health (60). In each of these areas, Center members make important contributions. In the future, COEC’s relationships and programs will increasingly focus on converting education and engagement into effective public health outcomes that improve children’s health. 7.9. Research Grant Base and Relevance to Environmental Health Figure 6 lists the grant funding of members that supports their current and proposed research activities (Appendix 1). The titles of the awards make clear that the large majority of the grants are explicitly directed toward research problems in environmental health (Table A.1). Others support basic biological research Figure 6. Center Investigator Grant in key areas of the Center’s scientific portfolio. In aggregate, current grants Support 2013-2019 total $75,100,000 in direct cost funding. For the time frame of this application, Current $75,100,000 Center investigators have grant funding that is well distributed throughout the 20131 $17,900,000 2014-2018 period (Figure 6). Among the competitively funded grants are 11 2014 $24,600,000 2015 $16,300,000 from NIEHS, including 3 RO1s (Miller, Heideman, Peterson), 1 R00 (K99) 2016 $ 6,000,000 (Laiosa), 1 R25 (Petering), 1 R24 (North), and the current CEHSCC P30 2017 $10,300,000 NIEHS grants 11 grant, 25 from other NIH institutes and numerous other awards. The end Other NIH grants 25 dates of 3 of the NIEHS grants (Heideman, Miller, and Peterson) fall beyond Other Federal grants 11 the February 13, 2015 requirement. During 2009-14, the Center has Other grants 25 averaged 5.5 R01 and R21 awards per year. 8. Strategic Program of the Center 8.1. Overview The CEHSCC is devoted to providing effective support for member’s research and community engagement. It does so through the program that the Center offers. The program is introduced here; other parts of the proposal provide the details to understand and evaluate it. 8.2. Organization (Aims 1-4, from section 2) Inter-institutional Foundation of the Center The CEHSCC was founded as an inter-institutional alliance (Figure 1). It will continue to develop as a regional center of children’s environmental health research and community engagement. Center Organizational Structure The administrative structure organizes and delivers the Center’s program support for research and community engagement (Figure 7). The Administrative Core oversees three facility cores that provide an abundance of research support for members across the translational path (8.4.5). Complementing the research infrastructure, the COEC integrates the Center’s scientific expertise with the needs of local communities. In addition, the Administrative Core supervises a robust and effective Pilot Project Program and leads the entire Center in supporting a diversity of career development initiatives for members and others related to the mission of the Center. These programs and activities are discussed below and elsewhere in the proposal. Center Leadership: Center NIEHS Director, Deputy Director, and External Advisory Others The leadership challenge Administrative Core Committee Institutions Directors: Petering, North J. Stegeman, Chair is to facilitate and integrate the UWM, CRI Ad. Staff: Schmidt, Gripentrog MCW, Children’s Pilot Project Program: Hoffmann, Petering talents and resources distributed Internal Advisory Hospital Career Development:Avner, Etzel, Sampath Committee among different physical sites and across the translational research spectrum. The executive team of Integrative Health Sciences Community Outreach Exposure & Aquatic Animal Facility Core & Engagement Core Biological Analysis Director and Deputy Director from Models Facility Core Hewitt Etzel, Hoffmann, Tonellato, Core Tomasiewicz, UWM and CRI/MCW bring to this Weber,Kosteretz -Epidemiology Research Unit North, Tomasiewicz , -Aquatic Animal Facility -Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Petering task complementary expertise and Stakeholders -Neurobehavioral Research Unit -Imaging and Histology Advisory Board common purpose. They contribute Toxicology Facility -Genomics -Exposure Assessment -Genome Modification diverse backgrounds in basic and Facility translational science, deep commitment to community Figure 7. Center Administrative Structure engagement, extensive, relevant administrative experience, and, importantly, a history of working closely together within the Center. Director David H. Petering is University Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry (UWM) and Adjunct Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Dr. Petering directed the NIEHS P30 MFBS Center between 1987 and 2009 and has overseen its transition to a full CEHSCC. He has been continuously funded by NIEHS for more than 30 years. In 2005 Petering ranked in the top 5% of investigators in cumulative NIH funding since 1980 (personal communication, Pierre Azoulay, MIT Sloan School of Management). With 220 publications in the broad area of metals in biological systems, Petering has an extensive record of research in metal toxicology, including studies of (i) the chemical-biological mechanism of cadmium inhibition of sodium-dependent nutrient transporters in kidney proximal tubule (29,30); (ii) chemical, biochemical, and cellular properties of the heavy metal binding protein, metallothionein that participates in protection against metals, oxidants and electrophiles (61); (iii) chemical and cellular mechanisms of heavy metal interaction with zinc-finger transcription factors (29, 62); and (iv) analytical tools to define the essential and toxic metal proteomes (30). A hallmark of his work is its interdisciplinary character, involving multiple collaborators in order to address questions ranging from the structure and reactivity of biomolecules to molecular and cellular biology. He is regularly called upon to write expert reviews (61, 62). Recently, Dr. Petering was named to the Editorial Board of Chemical Research in Toxicology, the premier journal focused on chemical mechanisms of toxicity. Petering also leads a long term, successful pre-college education program in environmental health funded by NIH/NIEHS. His collective experience has motivated the development of the CEHSCC as a highly interactive, first rate research organization complemented by an excellent engagement program. Paula North, MD-PhD (MCW), Deputy Director, is Medical Director of the Dept. of Pathology at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin and Chief of Pediatric Pathology at MCW. She is the Director of the EBAC research Core, PI of an NIEHS R24 grant to establish a GeoHealth Hub for environmental health in Peru, and leads the Unexplained Infant Death Center. North provides the CEHSCC with significant laboratory research experience on children’s health and is a highly respected leader within the CRI and the CHHS. Dr. North brings great strength to the Center’s objective to develop physician-scientists. The Center has also attracted into leadership positions other stellar scientists. Ruth Etzel, MD,PhD, Professor of Public Health, UWM, has become Director of the IHSFC. Dr. Etzel is internationally recognized in children’s environmental epidemiology and global environmental health (55-57,64). Exploiting her research background, support for community and clinical studies is unified within the Epidemiology Unit. The Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Research Unit within the IHSFC has attracted an international leader in bioinformatics, Peter Tonellato, to lead the new bioinformatics focus (65). 8.3. Center Membership (Aim 1) The Center maintains two categories of membership, Full Member scientists are fully engaged in and supported to conduct children’s environmental health research and include pilot project awardees (Administrative Core, 4). They have complete access to core resources. Associate Member designation connotes others with strong interests in children’s environmental health but who have not achieved independent research status. Such members do not have free access to Cores. This category of membership permits the Center to play a significant part in fostering the careers of promising young scientists and influencing investigators to focus their research on environmental health. Currently, the Center has 59 full members and 14 Associate members representing 23 academic disciplines (Figure 2). A primary responsibility of the Center Director and Deputy Director is to continually upgrade the quality of the Center membership roster. They can be effective to the extent that the CEHSCC is recognized as an important avenue for career development. Careers of excellent research and engagement flourish with the aid of early funding, access to critical infrastructure, and, often, important collaborators. A summary of the Center’s manifold support for career development is offered below. Administrative Core, Career Development Program, Pilot Project Program, and IHSFC sections provide full details of these support mechanisms. 8.4. Research and Community Engagement Capacity (Aims 1-3) A primary function of the CEHSCC is to enhance the capacity of member scientists to conduct meaningful research on problems in children’s environmental health and to connect their findings with various communities. In practice, this means (i) attracting strong investigators to the Center, (ii) stimulating interactions among them that generate an effective scientific community, including research collaborations and communication, and (iii) providing a wealth of supportive infrastructure that enhances research and engagement. During the past 3-4 years, the Center has established the foundation for intense, region-wide research collaboration in children’s environmental health. The sections below describe the Center’s ongoing strategy. 8.4.1. Regional Organizations Contributing to the CEHSCC Membership and Program The Administrative Core section details the Center’s relationship with the groups and organizations shown in Figure 1. Here, some of the initiatives supporting membership and program are briefly listed. UWM Zilber School of Public Health The ZSPH will hire two faculty each in Environmental and Occupational Health and Epidemiology in 2013-14. Most of the hires are anticipated to become Center members. School of Freshwater Sciences A key development for the Center’s future was the arrival in 2012 of the School’s founding Dean, David Garman. Already, the Dean has allocated significant institutional commitment to the Center in the form of additional space for the Aquatic Animal Models Facility Core (Institutional Organization and Commitment (IOC), 3.2.1). Children’s Research Institute-Children’s Hospital Of special importance is the Unexplained Infant Death Center, Paula North, Director, which serves as a partner in the children’s health inequities research initiative (7.6) (Appendix 2). It is providing funds for the Center’s pilot project program (IOC, 3.3). NEW Clinical Translational Sciences Institute The Center has arranged to partner with the CTSI to provide key clinical services for the Integrative Health Sciences Facility Core (IHSFC, 4). Milwaukee Health Department Director Petering has taken a lead role in the MHD (Public Health) Laboratory System Improvement Program, including acting as co-chair of its research committee. As this initiative matures, partnerships will increase in the area of children’s environmental public health. NEW Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene The Laboratory of Hygiene (WSLH) is a joint governmental-university unit of the State of Wisconsin. As part of its academic role, the Environmental Health Division of the WSLH has agreed to provide chemical analytical services to Center members on a collaborative basis. In so doing, the Center greatly enhances its research support capability (EBAC, 7). 8.4.2. Fostering Career Development and Research Community (Aims 1-3) The regional children’s environmental health community begins with attracting researchers with diverse talents and skills who value the Center for its support of their developing careers. It advances this goal by stimulating interactions and collaborations among its members through a variety of means. The Center will continue to grow as a highly interconnected community in the next grant period. To accomplish this trajectory, the Center offers a range of support mechanisms. Internal Advisory Committee The IAC is comprised of the executive leadership and heads of cores and programs in the Center, augmented by representative members. All are senior leaders, recognized by peers for their scientific background and expertise. Members meet monthly, work together, and model the larger Center community. The IAC takes responsibility for identifying potential new members and advancing superior cores and programs. Below we summarize enrichment activities that support the research community. All-Investigator Gatherings A primary tool that the Center uses to insure that members from across the region mingle, become acquainted, and begin to interact is the All-Investigator Gathering. Each year, the entire membership has met twice a year from 5-8 PM at a central location for scientific exchange and dinner. Attendance averages about 40. At a recent meeting, for example, MHD laboratory scientists were invited as a means to introduce them to the community. Dr. Steven Gradus, Director of the Laboratory, reviewed major local environmental health challenges and the Health Department’s role in resolving them. This was followed by informal theme-based discussions at designated tables. Emerging from this meeting were new partners for MHD scientists in the area of health inequities/infant mortality, including Dr. Venkatesh Sampath (MCW) and Dr. Joseph McGraw (Concordia University). In the future, these meetings will be increased to 3 per year. The formats will continue to vary–local or national speakers, posters, and multiple research and engagement roundtable discussions (e.g. health inequities, neurotoxicology, freshwater, community engagement, etc.). Research Interest Groups The Center supports interest groups that meet to discuss topical research and mutual interests in the area. The Center underwrites refreshments. More significantly, it offers the groups opportunities to invite external experts for seminars and to spend extra time with group members. Presently, groups in neurotoxicology/immunotoxicology, zebrafish model organism studies, and unexplained infant death convene at 1-2 month intervals. For example, this past year, Dr. Steven Ekker, Mayo Clinic, and Drs. C. Konsitzke and Feng Wan, University of Wisconsin System Center for Biotechnology, presented seminars focused on new genomic-based methodologies that can be applied to the zebrafish model. Moving forward, other interest groups will be encouraged to form based on the area concentrations described in Appendix 1. NEW-2013 Translational Research Committee-Multi-disciplinary Teams and Incentives Moving beyond the informal opportunities presented by the All-Investigator Gathering, the IHSFC is leading the formal effort to enhance translational research in the Center and the formation of multi-disciplinary research teams. Comprised of senior scientists who have a grasp of the entire Center membership and research portfolio, the Committee meets with (new) investigators and potential partners to consider possible collaborative Research (IHSFC, 6.2.1). In addition, next year, the Center’s redesigned website will support this effort with a searchable site (Research and Engagement Resource Directory) containing information about members’ interests in research and engagement. NEW Mentoring of Faculty Supporting professional advancement of the next generation of environmental health scientists is a special emphasis. They are arriving in numbers at the ZSPH, the School of Freshwater Sciences, the Unexplained Infant Death Center, the CRI, etc. and offer great promise for children’s environmental health. The Center will focus (i) on a mentoring program for this group of scientists and (ii) on a Children Environmental Health Fellows program to develop physician-scientists (Career Development Program (CDP), 2.3.4.1 and ----). Seminar Program The CEHSCC seminar program provides members intellectual enrichment and stimulation in the broad area of children’s environmental health as well as opportunities to meet one another (CDP, 2.3.4.1). Moreover, seminars represent a primary means for the Center to promote interaction with the larger scientific community. The Center partners with existing series in the Zilber School of Public Health, the School of Freshwater Sciences, the Children’s Research Institute, etc. Communications To build community, most meetings are conducted in person with tele-conferencing as needed. Meetings take place at respective institutions or at a convenient central location in downtown Milwaukee. The Center leadership uses an email list-serve to communicate with the membership as a whole. This is complemented by information placed on the website, www.uwm.edu/CEHSC. Currently, the website is being renovated to provide a user-friendly Research Support Directory that will guide viewers to all of the Center’s resources and to a search tool of potential scientist collaborators (NEW) (Appendix 3). The website, press releases, and other media provide publicity for members’ research and engagement activities. 8.4.3. Inter-Center Community At the Fall, 2009 Center Directors meeting in Milwaukee, the CEHSCC led a session devoted to the question of inter-center cooperation. Would collaborations leveraging the collective expertise and infrastructure of Centers provide important opportunities to advance research and engagement? That discussion started a process culminating in a call from NIEHS for inter-center pilot projects in Spring, 2012 and 2013. To catalyze sharing of methods and technologies among Centers, the CEHSCC will offer services provided by our EBAC and AAMFC to other Centers at the same cost charged to its members. 8.4.4. Research Support (Aims 2,4) The CEHSCC offers an array of research support that (i) supplies scientists with excellent staff and state-of-the-art methodology and instrumentation, distributed along the translational research path; (ii) offers financial incentives to undertake multi-disciplinary research directed at complex problems through the Pilot Project Program. Pilot projects serve as a vital incubator of innovative, higher risk research; and (iii) provides start-up funding for new investigators to ensure that they have the resources to properly initiate their studies. In order to sustain this level of support, the Center obtains extraordinary commitment of resources from its institutional partners and will continue to acquire additional assets-funding and infrastructure-from other sources (e.g. grants and fundraising) to supplement its NIEHS grant award (ICO section). 8.4.5. Research Support - Advanced EBAC Facility Cores (Aim 4) Successful implementation of the - Imaging and histology -Chemical analysis Strategic Vision depends on provision of cutting-edge tools -Genomics and staff through the Center’s research Cores. The Cores -Biobanking Pathw ays of continue to develop to meet the needs of Center scientists. In Toxicity IHSFC many cases, research projects use multiple Cores that - Epidemiology studies: public health and clinical provide complementary, comprehensive services. Figure 8 -Biostatistics Childre n’s Health qualitatively portrays relationships between broad research -Bioinformatics & Inequities themes and Cores, emphasizing that the Cores are useful AAM FC across the three themes (based on review of Core usage -Animal studies -Behav ior tables and Research Progress Report-Appendix 1). The -Genomics Dev elopmental CEHSCC operates three multifaceted Cores: (i) the AAMFC, Toxicology COEC comprised of the Aquatic Animal Facility, Neurobehavioral -IHSFC partner Toxicology Facility, and Genome Modification Facility; (ii) the -Community engagement EBAC, offering imaging, histology, genomics, chemical Figure 8. Matching Cores and Research Projects exposure assessment, and biobanking; and (iii) the IHSFC with companion Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Units. As the research portfolio evolves, so do the Facility Cores. Thus, in the next grant period the AAMFC will provide specific pathogen-free zebrafish, added space for husbandry, and genome editing. The EBAC will offer new technical support for exposure assessment and access to infrastructure to conduct genomic analyses. The IHSFC contributes a streamlined Epidemiology Unit as well as a new Bioinformatics Subunit that supports genomic and database research. 8.5. Capacity for Community Outreach and Engagement (Aim 3) COEC plays the central role in the Center’s central objective to apply its research knowledge and results to meet community environmental health needs as described in 7.6. To succeed in facilitating bidirectional communication between the Center and communities, Director J. Hewitt collaborates specifically with the Epidemiology Research Unit of the IHSFC, with other Cores on an ad-hoc basis, and with numerous Center members (Figure 8). She and her staff spend much time interacting with community leaders and members to facilitate transparent communication and engagement in community-relevant environmental health initiatives. In this work, she is assisted by skilled outreach specialists who are trusted members of the African American and Hispanic communities. Providing oversight is a Stakeholder’s Advisory Board comprised of diverse members of Milwaukee communities and governmental agencies. With a foundation of community relationships and accomplishments in place, COEC will assume an increasingly prominent role in Center initiatives in the future.