Defining critically reflective work behaviour

advertisement

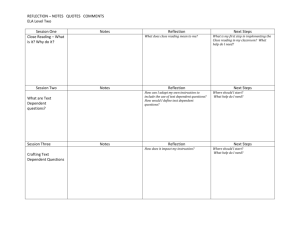

DEFINING CRITICALLY REFLECTIVE WORK BEHAVIOUR Marianne van Woerkom University of Tilburg, Department of Human Resources Studies m.vanwoerkom@uvt.nl Abstract Critical reflection is an import concept for improving the effectiveness of workrelated learning. However, there is not much consistency in definitions of critical reflection and the concept has not been developed operationally. This article describes a literature search, in order to define critically reflective work behaviour, a specific way of work-related learning. After an introduction on problems related to learning from experience, the article starts with a discussion of the concept of reflection as first defined by Dewey. Since the concepts of reflection and critical reflection are often confused, the next section describes the differences between them. Next, critical reflection is placed in the context of the workplace and the organisation. The article discusses respectively reflection as individual and social behaviour aimed at problemsolving, critical reflection on organisational values in a conflict model and a harmonious model, and critical self-reflection. Finally, the article discusses a way of making critically reflective work behaviour operational. Key words: Critical reflection, work-related learning. Introduction Daily experiences are an important source of work-related learning. Many of these learning processes will be implicit. We learn from our experiences without being aware of doing so, for example, from observing and imitating others, or from repetition. However, there are several problems related to implicit learning from experience. Much of this learning results in tacit knowledge, which is personal, context-specific, and therefore hard to formalise and communicate. Since tacit knowledge is beyond our perception, it is hard to change, even if we realise that the knowledge is not useful or no longer correct (Bolhuis, 1995). When tacit knowledge remains unexamined, it may lead to the reinforcement of misconceptions and prejudices, thus to the learning of errors, or no learning at all (Marsick & Watkins, 1990). Garrick (1998) also points out the danger of experiential learning leading to the reproduction of existing practices. Further, experiential learning can only be powerful when we see the consequences of our action, and then take a new and different action (Senge, 1990). However, this necessary feedback on our actions is often lacking, because the consequences of our actions will be observable only in the distant future, or in a distant part of the larger system in which we operate. When our actions have consequences beyond our perception, it becomes impossible to learn from direct experience. Further, although experience can be a source of learning, it can also impede learning when it leads to routine and fear of the unknown (Klarus & Van den Dool, 1988). Moreover, learning from experience is in a way suboptimal, because it is not directed towards learning goals (Simons, 1999). Boud, Keogh and Walker (1985) suggest that reflection is the key to learning from experience, and that we should sharpen our consciousness of what reflection in learning can involve, and how it can be influenced in order to improve our own practice of learning. However, there is not much consistency in the definitions of the concept of reflection (Brooks, 1999; Calderhead, 1989; Van Bolhuis-Poortvliet & Snoek, 1996). Some speak about reflection, while others speak of critical reflection, or critical thinking. It is often not clear what the difference is, or even if there is a difference between these terms. Since the concept of critical reflection has been developed within the context of theory or practice, rather than research, it has not been developed operationally, and no instrument exists to identify individuals capable of critical reflection (Brooks, 1999). This article discusses respectively the concept of reflection, the difference between reflection and critical reflection and critical reflection in the context of the workplace in order to come to an operational definition of critically reflective work behaviour. Reflection - the key to learning from experience? Many authors perceive Dewey (1933) as the founder of the concept of reflection. Dewey warned educators that mere ‘doing’ or activity was not enough to produce learning. Doing should become ‘trying’ - an experiment with the world, to find out what it is like (Raelin, 2000). Reflective thought is an “active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends” (Dewey, 1933, p.9). It involves not simply a sequence of ideas, but a con-sequence - a consecutive ordering, in such a way that each idea determines the next as its proper outcome, while each outcome, in turn, leans back on, or refers to, its predecessors (1933 p.4). Dewey (1933) distinguishes between five phases in reflective thinking (adjusted according to Van Bolhuis-Poortvliet & Snoek, 1996): 1. Although it is a natural reaction to immediately go into action, instead, an idea occurs about how to do this. 2. The person is confused by the situation, things do not turn out as expected; a problem has come up. 3. The first suggestion about how to solve the problem comes to mind in this phase. After this, the suggestion can be confronted with available information, in order to formulate a more definitive hypothesis, which serves to make further observation; 4. One reasons on the basis of earlier experiences or theoretical knowledge. 5. The hypothesis is tested in overt or imaginative action. 6. The hypothesis should not always be confirmed. In that case adjustments are made, after which the hypothesis is tested again. Many authors have defined reflection or related concepts inspired by Dewey. King and Kitchener’s (1994) theory on reflective judgement in a seven-stage model is inspired by Dewey, and especially by the idea that uncertainty is a characteristic of the search for knowledge. Marsick and Watkins (1990) define incidental learning in the workplace as part of an eight-phase model for a problem-solving model, based on Dewey’s theories. Boyd and Fayles (1983, in Brookfield, 1987) define reflection as the process of internally examining and exploring an issue of concern, triggered by an experience, which creates and clarifies meaning in terms of self, and which results in a changed conceptual perspective. Argyris and Schön (1996) define inquiry as the intertwining of thought and action that proceeds from doubt to the resolution of doubt. Doubt is construed as the experience of a problematic situation, triggered by the mismatch between the expected results of action and the results actually achieved. Many operationalisations of reflection or of related concepts inspired by Dewey, of which some examples have been given above, also consist of a phase model like Dewey’s (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985; Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988; Korthagen, 1985; Marsick & Watkins, 1990). Many objections can be made to these phase models (Korthagen, 1992). First, although such cyclical models clarify the process of reflection and the subsequent steps, they appear to describe more an ideal reflective process than reality. Steps such as observation and reflection are interwoven throughout various phases of the model. Further, there are hardly any examples that connect these phase models to empirical findings, and one might question if this is possible. There is not only the problem of reflective processes being less systematic in reality, but mainly the methodological problem of knowing what takes place in someone’s head. Another problem is that operationalisations are not aimed at measuring reflection directly, but at verbal expressions of it. Second, most phase models also share a common rationalistic bias (Ellström, 1999). Reflection is mainly approached as a rational cognitive process, where one step logically results from a previous step, and where emotions do not play a role. Boud, Keogh and Walker (1985) do give emotions a place, and see reflection as a generic term for intellectual and affective activities, in which individuals engage in exploring their experiences to come to a new understanding and appreciation. Third, most models approach reflection mainly as an individual and mental, instead of an interactive, dialogical action, while we know that feedback from others is generally considered to be necessary for learning to occur (Annett, 1969; Ellström, 1999; Frese & Altman, 1989, Marsick & Watkins, 1990). A fourth problem related to the concept of reflection is that it takes place within the frame of reference of an individual who is an internalisation of societal and cultural norms and values. This makes reflection a socially and historically embedded process, which is political, and thus shaped by ideology (Kemmis, 1985, in Garrick, 1998). Thus, just as implicit learning does not mean that this learning is ‘good’ or ‘true’, the same applies to reflection. Critical reflection explores the personal and social framework within which one works, rather than just working within it (Garrick, 1998). The next section will go more deeply into the differences between reflection and critical reflection. Reflection or critical reflection? As already stated, there is not much consistency in the definitions of the concept of reflection (Brooks, 1999; Calderhead, 1989; Van Bolhuis-Poortvliet & Snoek, 1996). Even Dewey (1933, 1938) sometimes uses the terms ‘reflective thinking’ and ‘critical thinking’ interchangeably (King & Kitchener, 1994). Some of the confusion about terminology seems to be caused by the different approaches that are involved. There seems to be a philosophical, a psychological, and a critical-pedagogical approach to the subject (Ten Dam & Volman, 2002). The philosophical approach seems to be represented by theories on reflection, inspired by Dewey, which are just discussed - approaching reflection as a norm for good, rational thinking. The psychological approach seems to be represented by theories conceptualising critical thinking mostly as a higher-order thinking skill (see Ennis, 1962). The critical-pedagogical approach refers mainly to the emancipatory goal of what is called critical reflection or critical thinking. It emphasises the identification and correction of political and social factors that limit the learner’s development. Theorists within this approach have all been influenced by the critical theory of the Frankfurt School. One important theorist within this stream is Mezirow (1990). He defines reflection in the Deweyan sense as instrumental learning; the assessment of assumptions implicit in beliefs about how to solve problems. In this definition, reflection thus also includes an element of critique, but refers more to instrumental thinking, which is concerned with how to solve a problem. In contrast, he defines critical reflection as addressing the question of the justification for the very premises on which problems are posed or defined in the first place, and examination of their sources and consequences. Critical reflection cannot become an integral element in the immediate action process, but requires a hiatus in which to reassess one’s meaning perspectives and, if necessary, to transform them. Meaning perspectives involve criteria for making value judgements and for belief systems, and are mostly uncritically acquired in childhood through the process of socialisation. Critical self-reflection refers to the most important learning experience. It means reassessing the way we have posed problems, our own meaning perspectives, and reassessing our own orientation to perceiving, knowing, believing, feeling, and acting. Brookfield (1987) also places critical thinking in an emancipatory perspective. He emphasises the ability of individuals to make their own judgements, choices, and decisions concerning their individual and collective future, instead of letting others do this, who presume to know what is in their best interest. Brookfield (1987) defines the process of critical thinking as the process by which we detect and analyse the assumptions that underlie the actions, decisions, and judgements in our lives. Brookfield emphasises that critical thinking involves more than logical reasoning or scrutinising arguments for assertions unsupported by empirical evidence. It also involves a reflective dimension, and means we can give justifications for our ideas and actions, and try to judge the rationality of these justifications. Critical reflection in the workplace In the previous sections, we have seen various theories about reflection and critical reflection. Most of the theories that are discussed are not aimed at the context of the work, but rather that of education or adult education. There are not many theories about critical reflection in the workplace. One explanation for this might be that the workplace is not the easiest context for critical reflection. Critical reflection is often considered soft and irrelevant to the resultsoriented and bottom-line world of business, and one might also question how critical critical reflection in the workplace can be, because the primary purpose of organisation is productivity (Marsick, 1988). In the previous sections, we have also seen that theories on reflection and critical reflection vary in their approach. Some emphasise the instrumental function of reflection in relation to problem-solving, whereas others emphasise the emancipation of the individual, in order to make free choices. Some emphasise critical reflection as an individual and cognitive activity, while others emphasise the social interaction. When studying the literature on reflection in the workplace, we recognise these different approaches in a few dimensions. The first dimension is reflection as an individual activity, aimed at solving the problems one encounters in one’s job (Mezirow’s reflection in instrumental learning). The second dimension is reflection as a social interaction, aimed at making tacit knowledge explicit or at problem-solving, as in continuous improvement or quality circles. The third dimension is critical reflection on the values of the organisation (Mezirow’s critical reflection in the communicative domain). Sometimes, this is approached in a conflict model by one individual challenging groupthink. Sometimes, it is approached in a more institutionalised conflict model - that of trade unions and workplace democracy. And sometimes, this is approached in a harmonious, but very Utopian model as in ‘Model II behaviour’ (Argyris & Schön, 1996). The fourth dimension refers to critical self-reflection, aimed at the emancipation of the individual in relation to the organisation. These dimensions cannot be seen as separate dichotomies, they are interrelated, and all touch upon each other. Individual reflection may lead to collective reflection; instrumental reflection may lead to critical reflection, and critical reflection on organisational values may lead to critical reflection on the self. One dimension thus cannot be seen as more important than another. The dimensions are discussed below. Reflection as individual behaviour aimed at problem-solving The relevance of this individual and instrumental approach to reflection hardly needs explanation; reflection is important to examine one’s experience, in order to assess its effectiveness and to improve performance. A very influential theory about reflection in the workplace in the instrumental problem-solving domain is the theory of Schön (1983) about reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Schön (1983) has researched how professionals think, and describes how thinking by problem-solving and reflection in practice develops. He distinguishes different moments when reflection takes place. Knowing in action refers to the knowledge, which is mostly tacit, that reveals itself from our actions. After we have learned something, most of the time people are able to carry out the required tasks without thinking, knowing in action is sufficient. However, sometimes, something unexpected will happen. We can react to these unexpected events by neglecting them (not learning) or reflecting on them. This may happen afterwards, by thinking back on what we have done. We then experiment in our mind by formulating new hypotheses. Reflection can also take place in action (thinking what you are doing while you are doing it), when there are still opportunities to experiment with alternative approaches. When someone reflects in action he becomes a researcher in the practical context. He is not dependent on the categories of established theory and technique, but constructs a new theory of the unique case. Reflection can make implicit knowledge explicit and criticised, and make room for new insights (reframing). Reflection as social interaction aimed at problem-solving We have seen that reflection as individual behaviour is often less effective than reflection in a social interaction. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) state that, although human cognition is a deductive process of individuals, it is never isolated from social interaction. In the concept of ‘externalisation’, they place reflection in a process of social interaction between individuals devoted to the development of new explicit knowledge out of tacit knowledge. Externalisation takes place when people attempt to conceptualise an image, expressing its essence in language. These expressions, however, are often inadequate, inconsistent, and insufficient. A process of collective reflection and interaction between individuals, driven by metaphors and analogies when an adequate expression for an image by analytical methods of deduction and induction cannot be found, results in a creative process leading to the new explicit knowledge. Another well-known example of collective reflection aimed at problem-solving, by focusing on procedures and methods, is continuous improvement or quality management. The ‘plan-do check-act circle’ that Deming (1986) introduced in order to reach continuous improvement resembles the reflection cycles that were discussed previously. First, the improvement is planned and the problems identified. Next, the idea for improvement is tested in practice on a small scale. Subsequently, the results of the experiments are gathered and, last, the successful action is standardised and implemented. According to Senge (1990), many initial attempts to establish quality circles failed ultimately in the U.S., despite making some initial progress. In the beginning, it leads to more open communication and collaborative problem-solving. However, the more successful the quality circles become, the more threatening they become to the traditional distribution of political power in the firm. Workers are afraid they are being manipulated by management, and that they might be shooting themselves in the foot (their job might be the next to go). Managers are often not prepared to share control with workers whom they have distrusted in the past. Frequently, the response of the leader to disappointing results adds fuel to the flame: the more aggressively he promotes the quality circle, the more people feel threatened. The above is a good example of the difference between reflection as problem-solving and critical reflection as problem-setting. Although reflection is useful for answering ‘how to’ questions - how to raise production, and how to reduce costs, it is not useful for the ‘why’ question - why are we participating in this quality circle in the first place? This brings us to the next section: critical reflection on organisational values. It also relates strongly to critical self-reflection aimed at the emancipation of the individual, which are discussed subsequentely. Critical reflection on organisational values Critical reflection on organisational values concerns conventional notions about work that are taken for granted, its relationship to progress and development, the usefulness of the goods being produced, the treatment of employees, and the uses (and abuses) of the natural environment and resources (Garrick, 1998). This dimension is related to critical selfreflection, because it underpins employees’ adaptations to it, and the tensions between ‘learning for work’ and ‘work for learning’ (Garrick, 1998). Although people often have a romantic view of communities of practice as learning communities and the locus of creative achievements, Wenger (1998) stresses that they can also reproduce counterproductive patterns, injustices, prejudices, etc., and can be the locus of inbred failures, resistance to oppression, and reproduction of its conditions. Communities of practice are also the place for espoused theories, general norms about what works that everybody agrees on (Schön, 1983). Espoused theories stand in contrast to theories-in-use, which refer to personal ideas based on intuition that professionals have about effective work strategies in relation to specific contexts and a readiness to change this strategy if the circumstances change. Critical reflection on organisational values in a conflict model Reflecting on espoused theory demands deeper and more critical reflection on values. Many people will keep theories-in-use private, because they contradict revered espoused theories. Even if espoused theories do not work, people will be afraid to criticise them, for fear of appearing incompetent, or being expelled from their professional group (Schön, 1983). Since most people avoid the problems and uncertainty of conflicts that innovative learning processes entail (Swieringa & Wierdsma, 1990), learning processes tend to be conservative, and confirm existing frames of reference (Weggeman, 1997). Thus, just as the process of critical reflection can be made possible through the assistance of facilitators, mentors, colleagues, family, or friends, because their feedback opens the learner up to other points of view (Marsick & Watkins, 1990), it also involves the ability to withstand social pressure. People who dare to criticise espoused theories are perceived as saying ‘the emperor is wearing no clothes’ or as ‘troublemakers’, as the participants in a company for telecommunication expressed it (Brooks, 1999). Although this was not regarded as bad, it was also often brushed aside, leaving the critically reflective worker alone. Brookfield (1987) refers to this as challenging groupthink - a critical attitude towards the ideas that a group of people consider sacrosanct. Rebellion often reveals a greater commitment than passive conformity (Wenger, 1998). The success rate of rebellion is limited by the organisational structure. Some organisations might foster rebellion, by giving opportunities for employee participation, in order to make the rebellion more collective and powerful, and also more institutionalised and harmonious (see the next subsection). Marsick (1988) pleads for a redefinition of productivity and a reexamination of conditions within the organisation, in order to create more opportunities for employee participation in the postindustrial era. Individuals are most productive when they can participate fully in negotiating meaningful contributions to shared organisational goals and norms. Brookfield (1987) also places critical thinking in the light of workplace democracy by stating that, in past years, the creation of labour unions was one of the greatest educational endeavours in which the American and British working class was involved, and the most important forum for critical thinking for blue-collar workers. Through critical participation, employees can hold those people in the organisation who take decisions responsible for their actions (Brookfield, 1987). Critical reflection on organisational values in a harmonious model A well-known theory about critical reflection on organisational values in a more harmonious model, aimed at organisational learning, is that of Argyris and Schön (1996). The difference between collective reflection, as in quality management, and their theory of organisational learning becomes clear from their critique of Total Quality Management focusing on technical solutions. As individuals working in a Total Quality Management search out the ‘root causes’ of defects in a product or process, they may identify two different kinds of problems. Inefficiencies in production represent one kind of problem; the other is illustrated by a group of employees who stand passively by and watch inefficiencies develop and persist. According to Argyris and Schön, Total Quality Management may produce the simple learning necessary to effect a solution to the first problem, but is unlikely to prevent a recurrence of the second. Argyris and Schön distinguish between the concepts of single and double-loop learning, which are used to characterise both individual learning and learning from organisations. Single-loop learning refers to instrumental learning that changes strategies of action or the assumptions underlying strategies in ways that leave the values of a theory of action unchanged. Double-loop learning is closely related to critical reflection. By double-loop learning they refer to learning that results in a change in the values of theories-in-use, as well as in its strategies and actions. It enables workers to identify, question, and change the assumptions underlying workplace organisation and patterns of interaction. Workers publicly challenge workplace assumptions and learn to change underlying values. By confronting the basic assumptions behind prevailing organisational norms, values, myths, hierarchies, and expectations, workers help prevent stagnation and dysfunctional habits. What is especially interesting for us about Argyris and Schön’s theory is that - in contrast to other authors - they give a very plausible answer to the question of why doubleloop learning is so difficult, and how this is related to individual behaviour. According to Argyris and Schön, double-loop learning is often prevented, because when people feel threatened, they reason and behave in accordance with a theory of action called Model I theories-in-use, enhancing conditions for error. Important features of issues become undiscussable and their ‘undiscussability’ itself becomes undiscussable. People who operate by Model I assumptions always seem to strive to satisfy four basic values that govern their behaviour. They define in their own terms the purpose of the situation, instead of developing a mutual definition of purposes with others. They want to maximise winning and minimise losing; once they have decided their goals, changing them would be a sign of weakness. They avoid eliciting negative feelings, because this would show ineptness, incompetence, or a lack of diplomacy. And, finally, they always try to appear rational; their interactions should be construed as objective discussions of the issues, whatever feelings may underlie them. The alternative is Model II behaviour. Here we can see the difference between the conflict model we saw in the theories of Brooks (1999) and Brookfield (1987) and the more harmonious model of Argyris and Schön. The ‘governing’ variables of Model II are to produce valid information, to make free and informed choices, to develop internal commitment to those choices and constant monitoring of their implementation, and the bilateral protection of others. Model II is not contradictory to Model I, and does not reject advocating one’s own goals. It does, however, reject unilateral control. Model II couples articulateness and advocacy with an invitation to others to confront the views and emotions of self and other. The pity is, however, that this harmonious model does not exist in practice, as appears from the statement that “we are unlikely to find the new learning system by looking at the world as it presently exists” (Argyris & Schön, 1996, p. 111). Organisations contain organisational learning with inhibition of double-loop learning embedded in Model I behaviour. They are highly unlikely to learn to alter its governing variables, norms, and assumptions, because this would require organisational inquiry into double-loop issues, which are militated by the learning system. Critical self-reflection Where Argyris and Schön’s (1996) theory is clearly devoted to promoting the organisational goal of organisational learning, in critical self-reflection the interests of the individual are central. Critical self-reflection in the context of the workplace means asking fundamental questions about one’s own identity as a member of the community of practice and the need for self-change (Marsick, 1988), aimed at self-realisation and development. This does not mean that the organisation does not benefit from critical self-reflection. Both organisations and the individuals working in them benefit from employees who reflect on themselves and ask themselves if they really want to follow the changes in their job, or if they would not prefer to look for another job. Since learning transforms who we are and what we can do, it is an experience of identity. It is not just an accumulation of skills, but a process of becoming – to become a certain person or, conversely, to avoid becoming a certain person (Wenger, 1998). Apart from a process of transforming knowledge, it thus also entails a context in which to define an identity of participation. Wenger (1998) stresses that communities of practice are not intrinsically benevolent for the individual: they are the cradle of the self, but also the potential cage of the soul. Critical self-reflection refers to learning to participate critically in the communities and social practices of which a person is a member, and creating an identity in relation to this specific social practice (Ten Dam & Volman, 2002). The instrumental approach to learning by reflection cannot be separated from critical self-reflection, because job-related knowledge and skills cannot be separated from the rest of the worker’s life (Marsick, 1988). Through critical self-reflection, people can better see the way in which taskrelated learning is often embedded in norms that also impact on their personal identity. Making critically reflective work behaviour operational This article has discussed various aspects of reflection and critical reflection. Let us now turn back to the aim of this article: an operational definition of critical reflection in terms of concrete individual behaviour with a high reality value for the process of work in organisations. Since the concept of critical reflection has been developed within the context of theory or practice, rather than research, it has not been developed operationally, and no instrument exists to identify individuals capable of critical reflection (Brooks, 1999). Further, definitions often seem to characterise a process, instead of visible behaviour, and many definitions are focused rather on learning or thinking than on working in an organisation. In order to overcome these problems case studies of seven organisations in both services and industries that were earlier carried out to describe work-related learning (see Van Woerkom, 2003) were again analysed to look for identifiable, concrete, and practical examples of the different dimensions of reflection identified in the previous section. In these organisations, senior managers, line managers and shop-floor workers were interviewed. The analysis resulted in seven dimensions of critically reflective work behaviour. These dimensions were later also validated in a self-report instrument tested on 742 respondents working in various sectors (Van Woerkom, 2003). Below the seven dimensions will be explained with examples from theory and practice. Reflection The reflection dimension is a combination of an instrumental function in problem-solving and a function in critical self-reflection with regard to one’s own identity in relation to the job. Reflective workers attempt to understand how suggested solutions fit in with their own image of themselves, and see the way task-related learning is often embedded in norms that also impact on their personal identity (Marsick, 1988). In the case studies, the importance of reflection was demonstrated by statements from respondents like “reflecting on the whys and wherefores”; “Why are things organised like this?” “Can the work be done more efficiently?” “Why do I work like this?” “Employees should be able to step back occasionally from their daily routine and devote more attention to self and time management”. The more critical dimension of reflection referred to reflecting on the work contributing to self-development. Sometimes, managers referred to this because they were stuck with dissatisfied employees, who did not want to look for another job because of their fear of the unknown, or attractive employment conditions in their current job. Critical opinion-sharing Critical opinion-sharing is one of the observable activities caused by reflection. One expresses the result of reflection by expressing one’s opinion, asking critical questions, or suggesting improvements. The opinion may concern a view or an idea of a valued outcome, which represents a higher-order goal and a motivating force at work (West, 1990). Making your opinion public is one of the two central aspects of Model II behaviour (Argyris & Schön, 1996). The respondents in the case studies stressed the importance of contributing ideas and discussing them with others. “Good critical workers are not just being negative, but make suggestions about a different way of working.” Asking for feedback The essence of the Model II behaviour of Argyris and Schön (1996) is the balance between advocating and inviting others for feedback and opinion-sharing. Feedback is generally considered to be necessary for learning to occur (Ellström, 1999; Annett, 1969; Frese & Altman, 1989). The functions of feedback are assumed to be cognitive as well as motivational. The importance of this dimension is demonstrated by statements from respondents referring to a social dimension of critically reflective work behaviour. On the one hand, social interaction is an important source of information for reflection. On the other, ‘being critical on your own’ is often perceived as not being constructive or effective. Employees operate in a social context, and will have to get support for their ideas to make things happen. Challenging groupthink Critically reflective work behaviour cannot always be based on harmony with the social environment. Since communities of practice can reproduce false assumptions and counterproductive practices, people are sometimes needed to criticise espoused theories, thus risking a conflict. Brooks (1999) referred to this as ‘saying the emperor is wearing no clothes’, or as being a ‘troublemaker’. Brookfield (1987) referred to this as ‘challenging groupthink’ - that is, ideas that a group has accepted as sacrosanct. Although not many respondents in the case studies mentioned ‘challenging groupthink’ based on the notions of Brooks and Brookfield, it was decided to distinguish between ‘opinion-sharing’ and ‘challenging groupthink’ as two different categories of critically reflective work behaviour. Learning from mistakes Reflection leads to consciousness of undesirable matters (for example, work routines, communication deficiencies, mistakes, problems, lack of motivation). Instead of denying these undesirable matters, learning from mistakes means to interprete them as something positive, namely as a source of improvement or learning. Negative feedback in the form of errors, although potentially frustrating, is particularly useful for facilitating learning (Frese & Altman, 1989, in Ellström, 1999). Errors may help to correct false assumptions, to break down premature or inadequate ‘routinisation’, and stimulate exploration and new discoveries (Ellström, 1999). Learning from mistakes involves not covering them up or reacting defensively when confronted with an error (Argyris & Schön, 1996). Learning from mistakes is thus both an individual activity and a social activity when it refers to hiding mistakes from others, thus limiting possibilities for oneself and others to learn from them. Here it touches upon the dimension of ‘asking for feedback’. Many respondents from the case studies stressed the importance of ‘not being afraid to make mistakes or show one’s vulnerability’. When managers were asked for their definition of ‘the learning organisation’, they often mentioned the importance of learning from mistakes. Experimentation According to Dewey (1933), mere doing is not enough to produce learning: doing should become trying, an experiment with the world to find out what it is like. Schön distinguishes between reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action. Reflection-in-action is a kind of experimentation. When someone reflects in action he becomes a researcher in the practical context. He is not dependent on the categories of established theory and technique, but constructs a new theory of the unique case. Experimentation is often mentioned as a last step in a reflection cycle (for example Dewey (1933), Korthagen (1985), Van Bolhuis-Poortvliet and Snoek (1997) or in the Deming circle. Although the term ‘experimentation’ was not mentioned by respondents (it has a connotation of experimentation without any obligations), what they did mention was the importance of putting ideas into practice. “Good teams don’t need a suggestions box; they immediately turn ideas into improvements.” Career awareness Career awareness can be seen as a logical consequence of the more critical aspect of ‘reflection’, aimed at self-development. As a result of this, people become aware of their motives and the extent to which work satisfies their motives. Career awareness refers to the intention to match self-development with career development, and, if necessary, to orient towards opportunities outside one’s current job or employer. It turned out from the case study material that career awareness was stressed by many respondents. It is not only in the interests of the employee, but also in those of the employer, if, for example, jobs change or disappear, and employees are dissatisfied with their changed job but cannot be dismissed, because they are protected by law. However, it turned out that many employees refuse to focus on other opportunities outside their current job, even if they are unhappy in it. Conclusion This article describes a process of literature search and a second analysis of the case studies, in order to come to an operational definition of critically reflective work behaviour. First, we have seen that implicit learning from experience, resulting in tacit knowledge has several disadvantages. Reflection when things do not go as we expected and experimentation with alternatives seemed to be an escape from these problems. We have seen some disadvantages of approaching reflection in the tradition of Dewey in a cyclical model. It is obvious that, besides some individual reflection activities like experimentation, our definition of critically reflective work behaviour must also include social interaction. The distinction between reflection as being instrumental in problem-solving and critical reflection, emphasising the assessment of underlying values (problem-solving versus problem-posing) made clear that we need both dimensions in our definition. A literature review led to five dimensions of reflection and critical reflection in the workplace, giving us some directions for operationalisation. In our second analysis of the case studies, we recognise these dimensions in seven aspects of critically reflective work behaviour. We can now define critically reflective work behaviour as a set of connected activities carried out individually or in interaction with others, aimed at optimising individual or collective practices, or critically analysing and trying to change organisational or individual values. Table 1 Eight dimensions of critically reflective work behaviour, ordered by level of reflection and individual or social activity. Reflection Individual activity - - Learning from mistakes - - Experimentation - - Reflection Critical reflection Critical self-reflection Social activity - - Learning from mistakes. - - Critical opinion-sharing - - Asking for feedback - - Challenging groupthink - - Reflection - - Career awareness In Table 1 we see the seven dimensions of critically reflective work behaviour ordered by level of reflection and by individual or social activity. Reflection, career awareness, and experimentation are individual activities. Critical opinion-sharing, asking for feedback and challenging groupthink are activities carried out in interaction with others. Learning from mistakes is both an individual activity and a social activity when it refers to hiding mistakes from others, and thereby limiting possibilities for oneself and others to learn from them. The learning from mistakes and experimentation dimensions are dimensions that refer to reflection as instrumental in relation to problem-solving. Critical opinion-sharing and asking for feedback refer to critical reflection on the organisational values departing from a harmonious model. Challenging groupthink refers to critical reflection on the organisational values departing from a conflict model. The reflection dimension is a combination of an instrumental function in problem-solving and a function in critical self-reflection with regard to one’s own identity in relation to the job. The career awareness dimension refers to critical self-reflection on the position of the individual in his current job. In conclusion, this operational definition of critically reflective work behaviour might help organisations and the individuals working there to learn more effectively from their daily experiences. It also might help researchers in studying work-related learning and critical reflection in the context of work. References Annett, J. (1969). Feedback and human behavior. Baltimore: Penguin Books. Argyris, Ch., & Schön, D.A. (1996). Organizational Learning II: Theory, method and practice. Reading Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing company. Bolhuis, S. (1995). Leren en veranderen bij volwassenen, een nieuwe benadering. Bussum: Coutinho. Bor, J., & Petersma, E. (Red.) (1995). De verbeelding van het denken. Geïllustreerde geschiedenis van de Westerse en Oosterse filosofie. Amsterdam, Antwerpen: Uitgeverij Contact. Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (Eds.) (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Brookfield, S.D. (1987). Developing critical thinkers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Brooks, A.K. (1999). Critical reflection as a response to organizational disruption. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 3, 67-97. Calderhead, J. (1989). Reflective teaching and teacher education. Teaching and teacher education, 5 (1), 43-51. Carter, M., & West, M.A. (1998). Reflexivity, effectiveness, and mental health in BBC-TV production teams. Small group research, 29 (5), 583-601. Deming, W.E. (1986). Out of the crisis: quality, productivity and competitive position. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: Heath & Co. Dewey, J. (1959). Experience in education. Kappa, Pi, lecture series. New York: Collier. Ellström, P.E. (1999). Integrating learning and work: problems and prospects. Contribution to the Forum workshop Learning in Learning Organisations. University of Evora. Ennis, R.H. (1962). A concept of critical thinking. Harvard Educational review. 32, (1), 81111. Frese, M., & Altman, A. (1989). The treatment of errors in learning and training. In L. Bainbridge & S.A. Ruiz Quintanilla (Eds.), Developing skills with information technology, (pp. 65-86). Chicester: John Wiley & Sons. Garrick, J. (1998). Informal learning in the workplace. Unmasking human resource development. London: Routledge. Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner (third edition) Geelong: Deakin University Press. King, P., & Kitchener, K. (1994). Developing reflective judgment. San Francisco: JosseyBass. Klarus, R., & Dool, P.C., van den (1988). Het ontwerpen van leerprocessen. Cultuurhistorische theorie over educatieve praktijken. Baarn: Anthos. Korthagen, F.A.J. (1985). Reflective teaching and pre-service teacher education in the Netherlands. Journal of Teacher Education, 36, (5), 11-15. Korthagen, F.A.J. (1992). Reflectie en de professionele ontwikkeling van leraren. Pedagogische Studiën, (69), 112-123. Marsick, V.J. (1988). Learning in the workplace: The case for reflectivity and critical reflectivity. Adult education quarterly, 38, (4), 187-198. Marsick, V.J., & Watkins, K.E. (1990). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. London: Routledge. Marsick, V.J., & Watkins, K.E. (1997). Lessons from informal and incidental learning. In J. Burgoyne & M. Reynolds (Eds.), Management learning: Integrating perspectives in theory and practice, (pp.259-311). London: Sage. Mezirow, J., and associates (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: a guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers. Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge creating company. How Japanese Companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press. Raelin, J.A. (2000). Work-based learning. The new frontier of management development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books. Senge, P.M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. London: Doubleday. Simons, P.R.J. (1999). Three ways to learn in a new balance. Life long learning in Europe, 14-23. Swieringa, J., & Wierdsma, A.F.M. (1990). Op weg naar een lerende organisatie. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhof. Swift, T.A., & West, M.A. (1998). Reflexivity and group processes: Research and practice. Sheffield: The ESRC Centre for Organisation and Innovation. Taatgen, N.A. (1999). Learning without limits. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. (dissertation) Ten Dam, G., & Volman, M. (2002). Het sociale karakter van kritisch denken: didactische richtlijnen. Pedagogische Studiën, 167-183. Van Bolhuis-Poortvliet, G.A., & Snoek, J.P.A. (1996). Reflecteren op stage-ervaringen. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (dissertation). Van Woerkom, M. (2003) Critical reflection at work. Bridging individual and organisational learning. Enschede: Universiteit Twente (dissertation). Weggeman, M. (1997). Kennismanagement. Inrichting en besturing van kennis intensieve organisaties. Schiedam, Scriptum. Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. West, M.A. (1990). The social psychology of innovation in groups. In M.A. West & J.L. Farr (Eds.), Innovation and creativity at work: Psychological and organisational strategies, (pp. 309-333). Chichester: Wiley.