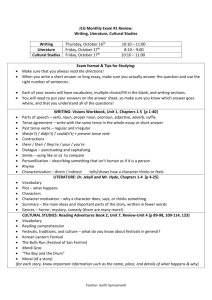

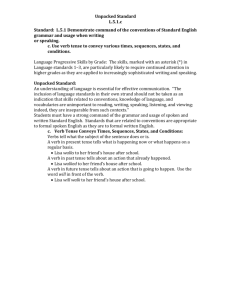

Tense and verb: Two agreements - Program for Disability Research

advertisement