INTERACTION ANALYSIS:

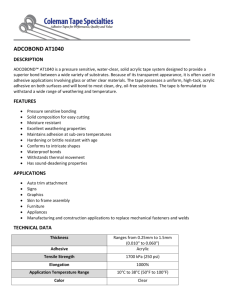

advertisement