GREATEST ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERY

advertisement

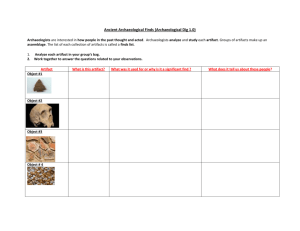

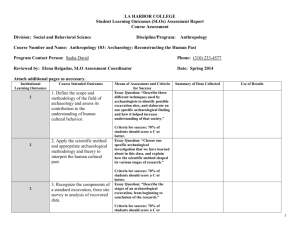

GREATEST ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERY DUE DATE: ____________________________________ TASK Archeology is the hands-on study of the past through careful excavation, study and leading to an enriched understanding of civilizations in history. The 20th century has seen many spectacular archaeological discoveries that have changed the face of ancient history and the legacies of ancient civilizations. Your task is to select and research one major archaeological discovery that has enlightened the modern world on how people and respective civilizations lived prior to the 16th century. INSTRUCTIONS 1. Read the attached article called The Ten Greatest Archaeological Discoveries of the Twentieth Century by Brian Fagan. 2. Select ONE discovery that interests you and research the find, you may choose one not on this list, as long as it relates to pre16th century history. Start your research at http://glebelibrary.wetpaint.com/page/History Stonehenge Tenochtitlan Rosetta Stone Machu Picchu Sutton Hoo Lascaux Caves Catal Huyuk Acropolis of Athens Terra-Cotta Army Cahokia Ozti Newgrange Harappa Mohenjo-Daro Royal Tombs of Ur Babylon Ishtar Gate Palace of Knossos Dead Sea Scrolls Tomb of Tutankhamen Pompeii Angkor Wat Uluburun 3. Together with a partner, research the following questions: Based on the archaeology discovery that you selected, what excavation procedures were used (tools, techniques, length of excavation, etc.)? What were the major conclusions, historical importance or impact of findings? Why was this discovery significant to the history of its specific civilization? How does this specific archaeological discovery meet the definition of legacy and importance of learning about the past? Format Criteria o You must be prepared to tell the class about your discovery o You must have at least one visual to show to the class The 10 Greatest Archaeological Discoveries of the Twentieth Century by Brian Fagan It was the century that saw our "caveman" ancestors change from mindless brutes to magnificent artists who put museum-quality images on the walls of French caves. It was a time when humanity's roots dug ever deeper — unimaginably deep — into the soils of an African past. The tomb of a boyking of Egypt, nicknamed Tut, showed the world what wealth and artistry meant in 1325 B.C. In the last 100 years, our understanding of the people of our past was fundamentally transformed. So was archaeology. At the last turn of the century, archaeology was still a gentlemanly pursuit conducted in pith helmets, jackets, and ties. Women were not taken seriously as excavators. Today we can identify, sometimes even map, archaeological sites from space, read ancient Maya glyphs, even reconstruct prehistoric menus. We can date individual wheat grains, use fossilized beetles to identify human settlements, excavate shipwrecks on the ocean floor, and decipher even the tiniest details of long-vanished landscapes. Only one thing remains unchanged: the compelling lure of the unexpected, of spectacular tombs, hidden gold, and long-forgotten ancient lives. Twentieth-century archaeology is a chronicle of discovery — of unsuspected cities and civilizations, surprising craftsmanship, artistry, and sophistication, of an ancestry that challenged the colonial and racial prejudices that filled the century's early years. In March 1900, Englishman Arthur Evans dug into a hillside at Knossos, Crete, and unearthed the Minoan civilization. Archaeology then was a small, incestuous club of excavators who knew each other well — and gossiped ferociously. World War I changed everything, wiping out a generation of younger scholars and giving hard-won military experience to others. During the 1920s, young Mortimer Wheeler used his wartime experience to refine the systematic 1880s' digging techniques of Victorian General Pitt-Rivers and revolutionized archaeological excavation. In the American Southwest, Alfred Kidder of Harvard University excavated Pecos Pueblo and developed the first cultural sequence of early Pueblo cultures. And, of course, there was Tutankhamun's tomb, which set the world agog and unleashed Egyptomania on the world. The 1920s and '30s saw the last of the huge and heroic excavations, among them Leonard Woolley's spectacular investigations at the Sumerian city of Ur. Woolley's fluent imagination brought the past to life in ways few archaeologists do today. Then adventure gave way to science. During the 1930s, young archaeologists like Grahame Clark of Cambridge realized the potential of wet sites to preserve much of ancient environments. When an amateur archaeologist found bones and stone tools in a glacial lakebed at Star Carr in northeastern England in 1947, Clark found what he was looking for: a Stone Age encampment with well-preserved organic remains. The Star Carr excavations of 1949-54 resulted in a brilliant reconstruction of Stone Age life 10,000 years ago, and it has served as an icon of ecological archaeology ever since. The second half of the twentieth century swept in with the discovery of radiocarbon dating. For the first time, archaeologists could date sites up to 40,000 years old and compare important developments — such as the appearance of farming or urban civilization — in widely separated parts of the world. The first radiocarbon dates were crude, but they made possible global portraits of the early human past — the first accounts of world prehistory. What is the most important archaeological discovery of the last century? High on that list must be our dramatic, new perceptions of human evolution. Half a century ago, Neanderthals and the hoax of Piltdown Man held center stage. Eugene Dubois' Homo erectus was ignored. When a young anatomist named Raymond Dart described Australopithecus africanus, the "ape-human of Africa," in 1925, his colleagues insisted he was wrong. Then, in 1959, Louis and Mary Leakey unearthed the robustlooking Zinjanthropus boisei and, a year later, Homo habilis at Olduvai Gorge in East Africa. Back then, most experts still dated human origins to a few hundred-thousand years. The potassiumargon dating of the Olduvai fossils to 1.75 million years ago transformed our perceptions of human evolution and revolutionized the story of our beginnings. Archaeologists of the twentieth century gave us our first clear understanding of the roots of human biological and cultural diversity. This prehistory of human diversity ranks among the greatest scientific achievements, for our success in the twenty-first-century world will depend not only on our technology, but on our understanding of ourselves. The following pages list, in no particular order, our choices as the 10 greatest archaeological discoveries of the twentieth century. Our "Top 10" — somewhat arbitrary and as arguable as any other — was chosen by the editors of Scientific American Discovering Archaeology, with advice from our editorial advisory board of leading experts in many archaeological disciplines. Most of the Top 10 were paradigm-busters that changed the way archaeologists interpret the past. A few touched the public deeply, forging a new appreciation for the wonders of our ancestors. And then there is the eleventh discovery — a spectacular find from the laboratory of a chemist, not the dig of an archaeologist. Its impact is so profound that we list it separately — the single greatest archaeological discovery of the century. BRIAN FAGAN is Professor of Anthropology at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and author of many popular books on archaeology. The Top Ten Discoveries 1. The Biblical Mystery in the Desert: The Dead Sea Scrolls Rewrote History for the Time of Jesus 2. Discovering the Tomb of Tutankhamun 3. A Bitter Tale of Old Bones: Finding the First American Meant Fighting the Status Quo 4. The Forgotten Glory of Ur: A Colorful Archaeologist and a Spectacular City Held the Public Eye 5. The Shipwreck at Uluburun: Underwater Archaeology Comes of Age 6. Ötzi, The Man in the Ice: A Human Face from the Late Stone Age 7. The Maya Finally Speak: Decoding the Glyphs Unlocked Secrets of a Mighty Civilization 8. In Search of Ancestors: The Leakey Family Rewrote the Origins of Humanity 9. The Artists of Lascaux: The Roots of Fine Art Run Deep into Our Past 10. China's Terracotta Army: Silent Soldiers Guard the Breathtaking Tomb of Qin Shihuang Greatest Archaeological Discovery – Formative Assessment Criteria Knowledge Thinking Re-Do Little or no understanding of the concept of legacy and insufficient details of the specific discovery/ artifact included. Demonstrates no ability to locate, select and organize information from appropriate sources. Communication Presentation is unclear and disorganized. No visual presented. Level 1 Limited understanding of the concept of legacy and few details of the specific discovery/ artifact included. Level 2 Approaching a clear understanding of the concept of legacy and some details of the specific discovery/ artifact. May be too general. Level 3 Demonstrates a clear understanding of the concept of legacy and the specific discovery/artifact. Level 4 Demonstrates an indepth understanding of the concept of legacy and relates many details about the specific discovery/artifact Demonstrates little ability to locate, select and organize information from appropriate sources. Demonstrates some ability to locate, select and organize information from appropriate sources. Demonstrates an ability to locate, select and organize information from appropriate sources. Presentation is not very clear and disorganized. Visual is inappropriate Presentation is somewhat clear. May not include all information. Visual may not be appropriate. Presentation is clear and organized. Visual is visible and appropriate. Demonstrates an ability to locate, select and organize information from appropriate sources in a highly effective manner. Presentation is clear and effective, highly organized. Visuals are visible, effective and appropriate. Levels Achieved: K ________ T ________ C _________ Learning Skills: Works Independently ______ Organization ______ Work Habits _______ Initiative ________