Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis (PBB)

advertisement

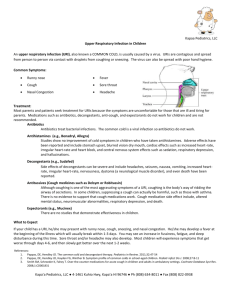

Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis (PBB) Anne B Chang1,2 1 Queensland Children’s Respiratory Centre and Queensland Children’s Medical Research Institute, Royal Children’s Hospital, Brisbane; 2 Child Health Division, Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin; Prof Anne Chang Queensland Children’s Respiratory Centre Royal Children’s Hospital, Brisbane, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia Tel: 61 7 36365270 Fax 61 7 36361958 Email: annechang@ausdoctors.net What is PBB? PBB, long been recognized by pediatric pulmonologists worldwide, was only adequately characterized (clinically and BAL) recently.1-3 PBB’s original description was derived from a prospective study that evaluated the aetiology of chronic cough in children using a research protocol. The study1 used a priori defined criteria and validated cough diaries to assess response with a clear time period relating to when medications were given. In the 108 young children with chronic cough in the study, bacterial infection of the airways (defined as growth of single pathogens of ≥105 cfu/ml) was the most common (40% of children) finding.1 Airway neutrophilia was also present and the respiratory pathogens found in the endobronchial infection were H influenzae, S pneumoniae and M catarrhalis.1,3 The criteria for PBB in the research study were; (1) history of chronic moist cough, (2) positive BAL culture, and (3) response to antibiotic treatment with resolution of the cough within two weeks. Outside of research protocols, bronchoscopies cannot be routinely undertaken for uncomplicated chronic wet cough in clinical practice. Thus PBB, sometimes truncated to protracted bronchitis (PB) is clinically defined as (a) the presence of isolated chronic (>4 weeks) wet/moist cough, (b) resolution of cough with antibiotic treatment and (c) absence of pointers suggestive of an alternative specific cause of cough.2 Hence while the diagnosis of PB can be suspected at the time of consultation, it can only be made down the track on review. PB has been officially recognized by the Thoracic Society of New Zealand and Australia and the British Thoracic Society.2 The clinical profile of children with PB Children with PB are typically young (<5 years of age, median age-3years1,3), do not have any other systemic symptoms including the absence of clinical sinusitis and ear disease. Some parents may report a ‘wheeze’ but it usually represents a misinterpretation of the sound.3 Many of these children have been misdiagnosed as having asthma.1,3 Their chest x-rays usually show peribronchiolar changes or may be reported as ‘normal’.1,3 Like children with chronic cough, children with PB have significant morbidity; parents typically have seen multiple medical practitioners for their child’s chronic cough in the last 12 months. In PB the child’s cough resolves only after a prolonged course of appropriate antibiotics (12-14 days). When a typical course (5 days) of antibiotics is used, the cough either relapses within 2-3 days, or slightly subsides but does not resolve completely. This is in contrast to the short course of antibiotics (5-7 days) required to treat community acquired pneumonia in otherwise well children. Children with PB also have higher Canadian Acute Respiratory Infection Scale (CARIFS) scores in subsequent respiratory illness. When compared with children with acute asthma and normal controls, children with PB, there was no difference between groups on day-1. However days 7, 10 and 14 later, children with PB had significantly (p <0.0001 for all) higher CARIFS scores.2 Pathogenesis of PBB PBB is associated with persistent bacterial infection in the airways1,3 and it is widely accepted that persistent bacteria infection (with accompanying inflammation) is harmful to the airways. PBB is likely non-homogenous with neutrophilic airway inflammation developing by a variety of mechanisms. It is likely that an innate immune dysfunction or immature adaptive immunity is present, at least in a subgroup of these children. A group of children with bacterial colonisation, airway neutrophilia and protracted cough that was unrelated to the presence or absence of oesophagitis, was identified from 150 children undergoing gastroscopy.4 In children without lung disease, cough was more likely to result from airway bacterial infection and not to esophagitis.4 The abnormal microbiology of the airways in children with cough, was not reflected in the microbiology of gastric juices. In a subset of these children (n=69), bacterial colonisation of the lower airways was associated with neutrophilic inflammation and reduced expression of both the toll-like receptor (TLR) -4 and the preprotachykinin gene, TAC1, that encodes substance P.5 Substance P has a defensin-like function which may explain the association between reduced TAC1 and persistent bacterial infection. In order to provide additional evidence for a dysfunctional host response to bacterial infection, chemokine receptor expression was assessed. Elevated gene expression for neutrophil chemo-attractant chemokine IL-8 cellular receptor, CXCR1, was detected, while the chemokine receptors (CCR3, CCR5) were similar between groups. In another cohort of children with established chronic cough who presented to respiratory physicians and had PBB, intense neutrophilic airway inflammation with marked inflammatory mediator response (IL-8, active matrix metalloproteinase 9 [MMP-9]) was present, compared to controls.6 The median levels of IL-8 (0.69, IQR 0.30, 1.72 ng/ml) in the BAL was similar to those found in other studies that examined chronic airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis and other forms of chronic suppurative lung disease.6 In contrast to above data, TLR-2 and TLR-4 mRNA expression were significantly elevated in this cohort when compared to the control group.6 However when corrected for neutrophil numbers (it remains unclear if values should be corrected), TLR-2 and -4 were reduced.6 Furthermore when followed up those with recurrent PBB has significantly reduced TLR-2 and 4 mRNA expression (adjusted values) compared to those who had did not have recurrent PBB in the 12-mo follow-up period (unpublished). Nevertheless there were other differences between these cohorts that include age (innate immunity is age-dependent), duration of cough and key presentation history. Thus the nature and duration of innate immune dysfunction remain undefined, nor is it clear whether the dysfunction is specific to the lower airways or is more generalised (ie systemic). Only a long term study will elucidate the pathogenesis and evolution of PB in children. Treatment and follow-up of children with PB Both the Australian and UK groups have described the response of the wet cough to a prolonged (at least 2 weeks) course of antibiotics.1-3 In a Cochrane review (albeit consisting of 2 limited studies with total number of 140 children), chronic wet cough in children responded to antibiotics with a number needed to treat of 3 (95%CI 2, 4) and the progression of illness, defined by requirement for further antibiotics, was significantly lower in the antibiotic group with a number needed to treat for benefit of 4 (95%CI 3, 5).2 However until a double blinded randomized control trial that specifically addresses this question is performed, it remains indefinite which children with wet cough should receive antibiotics. Children with PB may have recurrent episodes. In the Brisbane cohort’s preliminary study, approximately 35% of children have recurrent (> 2 episodes a year) PB. Also whether PB is antecedent to chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis in some children is unknown and important to evaluate. It is likely that, at least in a small but significant number of children, PBB is an early spectrum of the same process leading to chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis.2 Children with PB do not have established bronchiectasis as those with established bronchiectasis usually have a different clinical profile and are unlikely to recover after 12-14 days of oral antibiotics. It is suggested that children with recurrent PB (>2 episodes per year) are evaluated like a child with bronchiectasis. Summary In summary, chronic wet cough in young children is common and causes considerable morbidity and health care costs. A clinical diagnostic entity called PBB is the most common cause of chronic wet cough on young children. Even though many children with PBB get better with 2 weeks of antibiotics, the long term consequences in young children whose pulmonary system are still developing, remains undefined. In published preliminary studies, reduced levels of receptors involved in innate immune recognition in the BAL cells of children with PBB and airway infection were described. It is likely that, at least some if not many, children with recurrent PBB have innate immune dysfunction and are at risk of chronic suppurative lung disease, which has been lately recognised to be not as rare as previously thought. Studies elucidating the determinants of chronic airway inflammation and bacterial colonisation in children, in particular the role of innate immunity dysfunction in children with recurrent PBB and their clinical outcomes are required. References (1) Marchant J M, Masters I B, Taylor S M, Cox N C, Seymour G J, Chang A B. Evaluation and outcome of young children with chronic cough. Chest 2006; 129: 1132-1141. (2) Chang A B, Redding G J, Everard M L. State of the Art - Chronic wet cough: protracted bronchitis, chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2008; 43: 519-531. (3) Donnelly D E, Critchlow A, Everard M L. Outcomes in Children Treated for Persistent Bacterial Bronchitis. Thorax 2007; 62: 80-84. (4) Chang A B, Cox N C, Faoagali J, et al. Cough and reflux esophagitis in children: their co-existence and airway cellularity. BMC Pediatr 2006; 6: 4. (5) Grissell T, Chang A B, Gibson P G. Impaired toll-like receptor 4 and substance P gene expression is linked to airway bacterial colonisation in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 2007; 42: 380-385. (6) Marchant J M, Gibson P G, Grissell T V, Timmins N L, Masters I B, Chang A B. Prospective assessment of protracted bacterial bronchitis: airway inflammation and innate immune activation. Pediatr Pulmonol 2008; 43: 1092-1099.