Linguistic levels in cognitive linguistics

advertisement

Linguistic levels in cognitive linguistics

Abstract

What light does a cognitive perspective cast on one of the fundamental questions of

linguistic theory, the number of ‘levels’ or ‘strata’ into which linguistic patterns are

divided? Using purely cognitive evidence, such as the findings of psycholinguistics,

the paper argues that the relation between meaning and phonological form is mediated

by two levels: syntax and morphology. This conclusion conflicts not only with the

claim that all linguistic units are symbolic units which relate a meaning directly to a

phonological form, but also with the claim that they are constructions which provide a

single level that mediates between meaning and phonology. At least one other

cognitive theory, Word Grammar, does recognise both syntax and morphology as

distinct levels. The paper also discusses the relations among the levels, supporting the

traditional view that typically each level is related directly only to the levels adjacent

to it; but it also argues that in some cases a level may be related directly to a nonadjacent level. However, such exceptions can be accommodated by a four-level

architecture if the underlying logic is default inheritance.

1.

Syntax and morphology in cognitive linguistics

One of the issues that divides grammatical theories concerns the fundamental question

of how the patterning of language can be divided into ‘levels’ or ‘strata’, such as

phonology, grammar and semantics. The basic idea of recognising distinct levels is

uncontroversial: to take an extreme case, everyone accepts that a phonological

analysis is different from a semantic analysis. Each level is ‘autonomous’ in the sense

that it has its own units – consonants, vowels, syllables and so on for phonology, and

people, events and so on for semantics – and its own organisation; but of course they

are also closely related so that variation on one level can be related in detail to

variation on the other by ‘correspondence’ or ‘realization’ rules.

The question for the present paper is what other levels should be recognised.

Are sounds directly related to meanings, or is the relation mediated by words and

other units on an autonomous level of syntax? Similarly, we can ask whether words

are directly related to sounds, or whether that relation too is mediated by morphemes.

And if morphemes do exist, is there an autonomous level of morphology? The

question here is whether the morphological structure of a word is merely ‘syntax

inside the word’, or do syntactic and morphological structures represent different

levels of analysis? This was a hot topic for linguists in the 1960s, triggered by

Hockett’s article on Item-and-Arrangement or Item-and-Process analysis and

Robins’s reply recommending Word-and-Paradigm analysis as a superior alternative

to both (Hockett 1958, Robins 1959), and among morphologists it is still a matter of

debate; but it has been more or less ignored in cognitive linguistics. This is a pity,

because the ‘cognitivist’ assumptions of cognitive linguistics actually provide a new

source of evidence, and point reasonably clearly towards one answer. The aim of this

paper is to present the evidence, but also to argue that the conclusion requires some

serious rethinking in some cognitive theories of language.

What is at stake is the basic overall architecture of language. Does language

relate meanings directly to phonological (or perhaps even phonetic) ‘forms’, or is this

relation mediated by intervening levels? Leaving the debate about phonology and

phonetics on one side, we can recognise at least two levels: meaning and phonological

form (with written forms as an alternative to phonological/phonetic which, again, we

can ignore for present purposes). How many intermediate levels of structure do we

need to recognise?

Two answers dominate cognitive linguistics: none (Cognitive Grammar), and

one (the various theories other than Cognitive Grammar called ‘construction

grammar’, without capital letters, by Croft and Cruse 2004:225). Cognitive Grammar

recognises only phonology, semantics and the ‘symbolic’ links between them

(Langacker 2007:427), while construction grammar recognises only ‘constructions’,

which constitute a single continuum which includes all the units of syntax, the lexicon

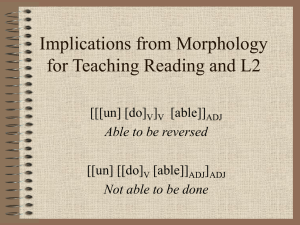

and morphology (Evans and Green 2006:753, Croft and Cruse 2004:255). In contrast,

many theoretical linguists distinguish two intervening levels: morphology and syntax

(Aronoff 1994, Sadock 1991, Stump 2001); and even within cognitive linguistics this

view is represented by both Neurocognitive Linguistics (Lamb 1998) and Word

Grammar (Hudson 1984, Hudson 1990, Hudson 2007, Hudson 2010).

To make the debate more concrete, consider a very simple example:

(1)

Cows moo.

The question is how the word cows should be analysed, and Figure 1 offers three

alternatives.

cow, >1

cow, >1

cow, >1

COW, plural

/kaʊz/

COW, plural

{cow}

{z}

{{cow}{z}}

/kaʊ/

/z/

/kaʊz/

(A)

(B)

(C)

Figure 1: From two to four levels of analysis

In each case, the form is represented by the phonological structure /kaʊz/ and

the meaning by ‘cow, <1’, which is obviously not a complete analysis in itself but

at least distinguishes the meaning clearly from any other kind of analysis. The

first analysis labelled (A) is at least in the spirit of Cognitive Grammar, with a direct

link between the meaning and the form. Analysis (B) is again in the spirit of both

Fillmore/Kay ‘Construction Grammar’ (with capitals) and Lakoff/Goldberg

‘construction grammar’ (Croft and Cruse 2004:257); in both these main constructional

theories, constructions mediate between the meaning and form, with syntactic and

morphological constructions sharing a single level where phrases consist of words and

words consist of morphemes. In the case of cows, the whole word combines the

lexical properties of COW with the grammatical category ‘plural’, so for simplicity it

bears the label ‘COW, plural’; but it also contains the morphemes {cow} and {z}. (I

use the term ‘morpheme’ in very concrete sense where it is quite different from a

‘morphosyntactic feature’; a morpheme is primarily an audible unit which can be

mapped to some part of phonology.) Analysis (C) is in the spirit of those theories that

distinguish morphology as an autonomous level from the level of syntax (for words);

so crucially the morphological unit labelled ‘{{cow}{z}}’ exists on a different level

of analysis from the word labelled ‘COW, plural’. In Figure 1, therefore, vertical lines

indicate a relation between relatively abstract and relatively concrete (i.e. ‘meaning’

or ‘realization’), whereas diagonal lines indicate a part:whole relation.

These diagrams claim to be ‘in the spirit’ of the theories mentioned, but the

notation is different from their official notations and could be accused of

misrepresentation. The reason for preferring lines, rather than the more familiar

boxes, is partly to make the theories easier to compare, but partly to reconcile

linguistic structures with the cognitivist assumption that linguistic knowledge is just

like other kinds of conceptual knowledge. We know that other kinds of conceptual

knowledge form a network; there is a great deal of experimental and other evidence

that this is so. For example, we know that activation spills over randomly, through

‘spreading activation’, to network neighbours to produce the well-known priming

effects and other kinds of association (Reisberg 2007:252). If general knowledge

takes the form of a network, and if language structures are just examples of general

knowledge, then it ought to be possible to convert any linguistic structure, such as a

‘box’ structure, into a network. All the structures in Figure 1 are obviously very

simple parts of a network in which each box is a node and each line is a network link.

The most important effect of replacing boxes by lines is to move away from

the very simple part-whole relations that have dominated linguistics, including

cognitive linguistics. Instead of seeing a unit such as a construction as a larger whole

with smaller elements as its parts, we can analyse it as a node in a network with links

to other elements which may or may not be smaller. This is important because there is

a great deal of uncertainty in the literature about what a construction contains; so in a

standard textbook (Croft and Cruse 2004) we find constructions defined variously as

‘a syntactic configuration’ (p.247), ‘structures that combine syntactic, semantic and

even phonological information’ (ibid.) and ‘pairings of syntactic form (and

phonological form ...) and meaning’ (p. 255). Given the box notation, it is important

to decide exactly what is inside the box for a construction and what is outside; but

network notation allows a construction to be a syntactic pattern with links to other

levels, without raising the question of whether these other links are inside the

construction or outside it. Tidying up definitions is rarely a productive activity, so

these questions are best avoided.

It is important to remember that the labels in Figure 1 do not refer to complex

units. Each label belongs to an atomic node without any internal structure at all, which

could be indicated by a mere dot. The label is merely a matter of convenience for the

analyst, and simply hints at further links which a fuller analysis would show; once

those links are in place, the label could be removed without any loss of information

(Lamb 1966, Lamb 1998:59). For example, the label ‘/kaʊz/’ identifies a syllable

consisting of two consonants and (arguably) a diphthong; and ‘cow, >1’

identifies a concept which has links to other concepts called ‘cow’ and ‘>1’.

Consequently, diagram (A) in Figure 1 could be replaced by the expanded network

in Figure 2, in which the labels have been replaced by a dot and the links to other

nodes. Clearly the same process could be applied to each of these other nodes, to give

a hypothetical ‘complete’ map of conceptual structure, without labels but tethered in

places to non-conceptual elements of cognition such as percepts and motor programs.

>1

cow

•

•

/k/

/aʊ/

/z/

Figure 2: Concepts are defined by links to each other

The question, of course, is which of these three analyses is right? When a

typical speaker of English hears or says the word cows, do they build a concept for

‘the plural of COW’, as opposed to the concepts ‘cow, >1’ for its meaning and

‘/kaʊz/’ for its pronunciation? And, if they do, do they also build one for its

morphological structure ‘{{cow}{z}}’? Note that all the possible answers are

equally ‘cognitive’, in the sense that they are compatible with the basic

assumptions of cognitive linguistics. None of them requires anything one might

call a ‘module’ of syntax or of morphology which is informationally encapsulated

(Fodor 1983) – indeed, a network analysis more or less rules out modularity

because activation flows freely through the network. Nor do any of them require

special cognitive apparatus which is only found in language. After all, ordinary

cognition must be able to analyse objects at different ‘levels’ in much the same

sense of ‘level’ as we find in linguistics; for instance, we can analyse an artifact

such as a chair in terms of its function (for sitting on), in terms of its relations to

other chairs (how it stacks or is fixed to other chairs), in terms of its structure

(legs, seat, back and so on) and in terms of its composition (wood, metal, etc).

These ways of viewing a chair are directly comparable to the levels of semantics,

syntax, morphology and phonology in syntax, so any mind capable of thinking in

levels about a chair can do the same for words. In short, the question of how

many levels to recognise in linguistics is not a matter of ideology or basic

assumptions, but of fact. What we need is relevant evidence to guide us in

choosing among the alternative theories.

2.

Are words mentally real?

The first question is whether our minds contain units of grammar (including both

syntax and morphology) as well as units of meaning and pronunciation or writing: in

short, do they contain words, phrases and morphemes? The relevant evidence comes

from psycholinguistic priming experiments, which offer a tried and tested way to

explore mental network structures (Reisberg 2007:257). In a priming experiment, a

person (the experimental ‘subject’) sees or hears input from a computer and has to

make decisions of some kind about the input, such as whether or not it is a word of

English. The dependent variable is the time (measured in milliseconds) taken by the

subject to register these decisions; for example, as soon as the word doctor appears,

the subject presses one of two buttons. The independent variable is the immediately

preceding word, which may or may not be related to the current word; for instance,

doctor might follow nurse (related) or lorry (unrelated). What such experiments show

is that a related word ‘primes’ the current word by making its retrieval easier, and

therefore faster. It is experiments like these that give perhaps the clearest evidence for

the view that knowledge is stored as a gigantic network, because it is only in a

network that we could describe the concepts ‘doctor’ and ‘nurse’ as neighbours.

Crucially, however, priming experiments distinguish the effects of different

kinds of priming. Semantic priming such as doctor – nurse is evidence for relations

among meanings (Bolte and Coenen 2002, Hutchison 2003), and phonological

priming such as verse – nurse proves that we have phonological representations (Frost

and others 2003). Neither of these conclusions is controversial, of course, but we also

find priming evidence for syntactic objects such as words and the abstract patterns in

which they occur (Bock and others 2007, Branigan 2007). For instance, in one series

of experiments where subjects repeated a sentence before describing an unrelated

picture, grammatically passive verbs primed otherwise unrelated passive verbs and

actives primed actives; so in describing a picture of a church being struck by

lightning, subjects were more likely to say Lightning is striking the church after

repeating the active sentence One of the fans punched the referee than after its passive

equivalent The referee was punched by one of the fans, and vice versa. Similar effects

appeared with the choice between ‘bare datives’ like The man is reading the boy a

story and ‘to-datives’ like The man is reading a story to the boy. These results are

hard to interpret without assuming the mental reality not only of abstract patterns like

‘active’ and ‘bare dative’, but of the words and word categories in terms of which

these patterns are defined.

The evidence from priming looks like firm proof, if we need it, that both

words and their syntactic patterning are mentally real. This conclusion, if true, is

clearly at odds with the basic claim of Cognitive Grammar that language consists of

nothing but phonology, semantics and the links between them:

..., every linguistic unit has both a semantic and phonological pole... Semantic

units are those that only have a semantic pole ... phonological units ... have

only a phonological pole. A symbolic unit has both a semantic and a

phonological pole, consisting in the symbolic linkage between the two. These

three types of unit are the minimum needed for language to fulfill its symbolic

function. A central claim ... is that only these are necessary. Cognitive

Grammar maintains that a language is fully describable in terms of semantic

structures, phonological structures, and symbolic links between them.

(Langacker 2007:427)

In this view, every linguistic category (other than purely semantic and purely

phonological categories) is a ‘symbolic’ unit that can be defined either by its meaning

or by its phonology. However, even for Langacker the claim is actually heavily

qualified so that it applies only to the most general categories such as noun and verb.

At the other end of the scale [from basic grammatical classes] are idiosyncratic

classes reflecting a single language-specific phenomenon (e.g. the class of

verbs instantiating a particular minor pattern of past-tense formation).

Semantically the members of such a class may be totally arbitrary. (Langacker

2007:439)

Presumably such a class is a symbolic unit (albeit a schematic one), but how can a

symbolic unit have no semantic pole, given that a unit without a semantic pole is by

definition a phonological unit (ibid: 427)?

It seems, therefore, that the experimental evidence from structural priming

threatens one of the basic tenets of Cognitive Grammar. There remain two ways to

rescue the theory: either by demonstrating that categories such as ‘passive’ and ‘bare

dative’ are actually semantic, or by accepting that they are idiosyncratic. Whether or

not either of these escape routes is feasible remains to be seen.

Another way to link these questions to experimentation is to predict the

outcome of experiments that have not yet been carried out. So far as I know, this is

the case with the following experiment: subjects are presented with pairs of

contextualized words that belong to the same abstract lexeme, but which are different

in both meaning and form. For example, they see two sentences containing forms of

the verb KEEP, such as (2) and (3).

(2)

He kept talking.

(3)

Fred keeps pigeons.

If words are truly symbolic units which unite a single meaning with a single form,

then sentence (2) should have no more priming effect on (3) than any other sentence

containing a verb with a roughly similar meaning (such as holds) or roughly similar

pronunciation (such as cups). But if words exist in their own right, with the possibility

of linking ‘upwards’ to multiple meanings and ‘downwards’ to multiple

pronunciations, kept in (2) should prime keeps in (3).

Cognitivist assumptions also allow a more theoretical evaluation of this tenet

of Cognitive Grammar. Given what we know about concept formation in general, how

would we expect people to cope mentally with the patterns they find in language? In

general cognition, we can mentally record a direct linkage between any two nodes

A and B, which we can call [A – B]. But suppose we also need to record that [A –

B] coincides with a link to a third node C, meaning that when A and B are linked

to each other – and only then – they are also linked to C. This three-way linkage

cannot be shown simply by adding extra direct links such as [A – C] because this

would ignore the fact that A is not linked to C unless it is also linked to B. The

only solution is to create a ‘bridge concept’ D, which links to all the three other

nodes at the same time; in this structure, D is linked to A, B and C, thus

expressing the idea that A and B are only linked to C when they are also linked to

each other. This general principle applies to any concept, such as ‘bird’, which

brings together properties such as having wings, having a beak and laying eggs.

In a network, the only way to bring these three properties together is to create a

new entity node, the node for ‘bird’, which has all three properties. More

generally, the only way to link three nodes to each other as shared properties is

to create a fourth node that links directly to all three.

Turning now to language, take the link between the meaning ‘cow’ and the

pronunciation /kaʊ/. Clearly a direct link, as predicted by Cognitive Grammar, is

one possibility, so we can easily imagine the concept ‘cow’ having a number of

properties, one of which is that its name is /kaʊ/, and conversely for the sound

/kaʊ/, whose meaning is ‘cow’. But this linkage is not isolated. It coincides with

being able to follow the, with allowing plural s, and with a host of other

properties. According to Cognitive Grammar, these properties can be expressed

semantically in terms of a general category such as ‘thing’. But that cannot be

right, because again it misses the complex linkage. An example of ‘cow’ can’t

generally follow the or take plural s; the properties of ‘cow’ include mooing and

producing milk, but not grammatical properties. These are reserved for cases

where ‘cow’ is paired with /kaʊ/ - and in those cases, ‘cow’ does not imply

mooing or milk. In short, the only way to distinguish the ‘cow’ that mooes from

the one that follows the is to distinguish the two concepts by creating a new one,

the word cow. This immediately solves all the problems by linking the

grammatical properties to general word-like properties. It is the animal ‘cow’

that mooes and produces milk, but it is the word cow that follows the and takes

plural s, as well as meaning ‘cow’ and being pronounced /kaʊ/.

The trouble with reducing a word to a single link between two poles is

that it prevents us from recognising it as an entity in its own right, with its own

generalizations and other properties. Mental words can be classified (as nouns,

verbs and so on); they allow generalization (using general concepts such as

‘word’); they can be assigned to a language (such as English or French); they can

have an etymology or a source language (e.g. karaoke comes from Japanese);

they can have lexical relations to other words (e.g. height is related to high); and

so on. The theoretical conclusion is that a grammatical analysis requires the

word cow, but this is not a symbolic unit, in Langacker’s sense.

This conclusion also undermines the claim that grammatical word classes

can be replaced by semantically defined symbolic units:

Some classes are characterized on the basis of intrinsic semantic and/or

phonological content. In this event, a schematic unit is extracted to

represent the shared content, and class membership is indicated by

categorizing units reflecting the judgment that individual members

instantiate the schema. (Langacker 1990:19)

Langacker’s examples include the claim that the unit which links the meaning

‘pencil’ to the form pencil instantiates the schema whose meaning pole is ‘thing’

and which corresponds to the notion ‘noun’. But if ‘noun’ is nothing but a pairing

of a form and a meaning, how can it have grammatical properties such as being

part of a larger schema for ‘noun phrase’?

Langacker’s notation hides this problem by using boxes for symbolic

units, as in Figure 3 (Figure 7a in Langacker 1990:18, with minor changes to

notation). Each box contains a symbolic unit, which allows the unit to be treated

as a single object; so the relation between ‘thing’ and X is shown as having a

part:whole relation to a larger whole, and having pencil/pencil as an example.

But if a unit is really just a combination of two poles and a relation, what is it that

has these properties? For instance, what is it that combines with other nouns to

form compounds such as pencil sharpener? Certainly not the concept ‘thing’ or

‘pencil’ – a pencil is a piece of wood, not something that combines with nouns;

nor is it the phonology, because that is not the defining characteristic of a noun;

nor is it the relation between the meaning and the form, because a relation

cannot combine with anything. The obvious answer is that each box is itself a

bridge concept, as explained above. But in that case, each box stands for a word,

and we have a level of grammar.

thing

X

process

Y

er

-er

pencil

pencil

sharpen

sharpen

er

er

Figure 3: Cognitive Grammar notation for pencil sharpener

Whatever cognitive evidence we consider, we seem to arrive at the same

conclusion: words, and their grammar, are cognitively real. We really do have words

in our minds. This conclusion is comforting because it reinforces what most

grammarians have claimed through the ages without paying any attention to cognition

– and, indeed, it supports the common-sense view, supported by language itself, that

we have words which we can recognise, learn to write and talk about. This commonsense view explains why we can classify words according to their language (English,

French and so on) and according to their social characteristics (posh, technical,

naughty, ordinary), why we can talk about their etymology, and even why some of us

can spend our working lives studying them.

3.

Are morphemes mentally real?

If words are mentally real, what about morphemes? Are they mentally real too?

Outside cognitive linguistics, opinion is strongly divided among morphological

theorists, many of whom argue that morphological rules relate words and word

properties directly to phonological patterns, without any intermediate level of

analysis. The most influential supporter of this view is probably Anderson, who called

it ‘A-morphous morphology’ (Anderson 1992), though many other morphologists

(e.g. Stump 2006) also allow words to be directly realized by phonology, even if they

also countenance the existence of morphemes. On the other side we find equally

influential morphologists such as Aronoff (Aronoff 1994) who assert that morphemes

are essential linguistic units mediating between syntax and phonology. Once again,

cognitive linguists have not yet contributed to this debate as they might have done,

given the amount of relevant evidence which is now available from cognitive

psychology.

Priming experiments show that morphological priming can be separated from

semantic, lexical and phonological priming (Frost and others 2000). Morphologicallyrelated words prime one another, and this is found even when the words are

semantically unrelated as in pairs such as hardly/hard and even corner/corn (but not

scandal/scan, where –al is not a morpheme). This effect only appears where the

priming word is ‘masked’ – presented so fast that the subject is not aware of it

(Marslen-Wilson 2006, Fiorentino and Fund-Reznicek 2009) – but it is robust and

provides very strong evidence for the reality of morphemes.

The difference between morphological priming and both semantic and

phonological priming is even clearer in Semitic languages such as Arabic and Hebrew

where the word stem consists (typically) of just three consonants, to which

morphology adds various vowels and extra consonants interspersed among the

consonants. For instance, in Arabic, the root {dxl} is associated with the meaning

‘enter’, and is found not only in transparent forms such as / idxaalun/ (‘inserting’)

and /duxuulun/ (‘entering’), but also in the semantically opaque word /mudaaxalatun/

(‘interference’); but any of these words primes the others, regardless of whether or not

they are transparent and also regardless of whether the prime is masked or overt

(Marslen-Wilson 2006).

A very different kind of evidence for the mental reality of morphemes comes

from sociolinguistics. In this case the data come not from experiments but from taperecorded spontaneous conversations by English speakers in the USA. The crucial

parts of the recordings were words which potentially end in a consonant followed by

/t/ or /d/, such as act or walked, in which many speakers can omit the /t/ or /d/. This

‘t/d deletion’ was studied by Guy in a series of projects in which he found a consistent

difference between the figures for omission of t/d according to whether or not it

realized the suffix {ed}, with omission much more likely in monomorphemic words

such as act than in words containing {ed} such as walked (Guy 1980, Guy 1991a,

Guy 1991b, Guy 1994, Guy and Boyd 1990). Guy’s explanation for this difference

assumes that the omission rule has more opportunities for applying to act than to

walked because it can apply both before and after affixes are added; an alternative

explanation is that words like act may have no final /t/ even in their stored form

(Hudson 1997). But either way, the status of /t/ as a morpheme or not is crucial. Even

more interestingly, Guy also found that semi-regular forms such as kept varied with

the speaker’s age: younger people treated them like monomorphemic words such as

act while older speakers treated them like bimorphemeemic words such as walked.

The only plausible interpretation is that speakers reanalysed their stored forms by

recognising the morpheme {ed} in examples like kept. If this interpretation is correct,

it provides strong evidence against a-morphous morphology and in favour of a level

where morphemes are distinguished from phonological structures.

A further kind of evidence from spontaneous speech comes from speech

errors, where examples such as (4) and (5) have been reported (Stemberger 1998:434,

Harley 1995:352)

(4)

I can’t keep their name straights. (for: their names straight)

(5)

I randomed some samply. (for: sampled some randomly)

In (4), we must assume that the speaker planned to attach {s} to {name} but

accidentally attached it instead to {straight}. This cannot be a simple phonological

transfer because speech errors rarely, if ever, involve the transfer of a mere phoneme

from one word to another; nor can they be due to syntactic or semantic confusion,

because there is no syntactic or semantic feature that might be realized by {s} after

attaching mistakenly to an adjective such as straight. In (5), in contrast, the error can

only be explained by assuming that the speaker intended to include the morphemes

{sample} and {random} but used them in the wrong words, whose only similarity (in

contrast with the other available words) is that they both contained a clear suffix.

Once again, the only reasonable interpretation presupposes the mental reality of

morphemes.

Another kind of argument for morphemes is based on the well-known

psychological process of ‘chunking’. We understand experience by recognising

‘chunks’ and storing these in memory as distinct concepts (Reisberg 2007:173). This

effectively rules out reductionist analyses which reduce the units of analysis too far;

for instance, a reductionist analysis of the sequence ‘19452012’ recognises nothing

but the individual digits, ignoring the significant dates embedded in it (1945, 2012).

Psychological memory experiments have shown that human subjects are looking for

significant ‘higher’ units in their experience, and it is these units, rather than the

objective string, that they recognise in memory experiments. A chunk based on a

collection of ‘lower’ units is not evidence against the cognitive reality of these units,

but coexists with them in a hierarchy of increasingly abstract levels of representation;

so the individual digits of ‘1945’ are still part of the analysis, but the sequence is not

‘merely’ a sequence of digits.

Applying the principle of chunking to language, consider now the so-called

‘phonological pole’ of a symbolic unit in Cognitive Grammar, or, for that matter, the

phonological form which may define a construction. Just as dates ‘chunk’ digits into

groups, so do symbolic units; so if the symbolic unit happens to be a word such as

patients, then it will be chunked into /peiʃnt/ plus /s/. But the first of these chunks is

not a unit of phonology – it is a syllable and a part of a syllable. This example

illustrates the mismatches between morphemes and units of phonology which show

that the two must be different. Such examples are numerous and much discussed in

the literature on morphology; for example, in the word feeling the /l/ that belongs

symbolically to /fi:l/ must nevertheless belong phonologically to /lɪŋ/ because the /l/ is

pronounced as a clear [l], a pronunciation which is only found at the start of a syllable

(in contrast with the dark [ɫ] at the end of /fi:l/ as pronounced without a following

vowel). The general point is that the chunks which constitute the ‘phonological pole’

of a symbolic unit such as feel in feeling are not, in fact, phonological. Rather, they

are the meaning-linked sections of phonological structure that are otherwise known as

morphemes; so the cognitive theory of chunking supports morphemes as independent

units.

Yet another kind of evidence which supports the mental reality of morphemes

comes from ‘folk etymology’, where learners try to force a new form into an existing

pattern, regardless of evidence to the contrary. For instance, our word bridegroom

developed out of Old English bryd-guma, ‘bride man’ when the word guma ‘man’

(cognate with Latin homo) fell out of use, leaving the guma form isolated (Partridge

1966:293). The form groom had the wrong meaning as well as the wrong phonology,

but it had the great virtue of familiarity – i.e. it already existed in everybody’s mind as

an independent concept – and was somewhat similar in both meaning and form so it

was pressed into service (‘recycled’) for lack of a better alternative. The fact that folk

etymology has affected so much of our vocabulary, and continues to do so (Bauer

2006), is clear evidence of our enthusiasm for recycling existing forms so that every

word consists of familiar forms, regardless of whether this analysis helps to explain

their meaning. Indeed, one could argue that recycling of existing concepts is a basic

drive in all cognition, including semantics as well as morphology (Hudson and

Holmes 2000).

The idea of recycling combines with chunking to provide a further argument

for morphemes which is based on homonymy. When we first meet a homonym of a

word that we already know, we don’t treat it as a completely unfamiliar word because

we do know its form, even though we don’t know its meaning. For instance, if we

already know the adjective PATIENT, its form is already stored as a single chunk; so

when we hear The doctor examined a patient, we recognise this form, but find that the

expected grammar and meaning don’t fit the context. As a result, when creating a new

word-concept for the noun PATIENT we are not starting from scratch. All we have to

do is to link the existing form to a new word. But that means that the existing form

must be conceptually distinct from the words concerned – in other words, the

morpheme {patient} is different from the words that we might label PATIENTadj and

PATIENTnoun. Wherever homonymy occurs, the same argument must apply: the

normal processes of learning force us to start by recognising a familiar form, which

we must then map onto a new word, thereby reinforcing a structural distinction

between the two levels of morphology (for forms) and syntax (for words), both of

which are different from phonology and semantics. The proposed analysis for the

homonymy of patient is sketched in Figure 4.

‘sick person’

‘good at waiting’

PATIENTadj

PATIENTnoun

/ei/

/ʃ/

syntax

morphology

{patient}

/p/

semantics

/n/

/t/

phonology

Figure 4: Homonymy and the levels of language

The evidence reviewed here points unequivocally to a single conclusion:

morphemes are distinct from both words and phonological structures, so our stock of

linguistic units must include morphemes as well as words, meanings and sounds. In

short, we can reject ‘a-morphous morphology’. But it is still possible that we only

need three levels of analysis; this would be the case if morphemes and words were the

same kinds of object and inhabited the same level. This is the last question, to which

we now turn.

4.

Are morphemes parts or realizations?

What is at stake in this section is a claim which Croft describes as ‘one of the

fundamental hypotheses of construction grammar’ (Croft 2007:471), that

constructions comprise a single continuum which includes all the units of syntax, the

lexicon and morphology. The question is whether morphology and syntax share ‘a

uniform representation of all grammatical knowledge’ because ‘construction grammar

would analyze morphologically complex words as constructions whose parts are

morphologically bound’. Like other cognitive linguists I fully accept the idea of a

continuum of generality from very general ‘grammar’ to a very specific ‘lexicon’; but

the claim that syntax and morphology are part of the same continuum is a different

matter.

As an indication of the complexities and depth of the issues involved here,

consider the claims of Construction Morphology, the most fully developed application

of construction grammar in this area (Booij 2010). On page 11, we find the following:

... morphology is not a module of grammar on a par with the phonological or

the syntactic module that deal with one aspect of linguistic structure only.

Morphology is word grammar and similar to sentence grammar in its dealing

with the relationships between three kinds of information [viz. phonology,

syntax and semantics]. It is only with respect to the domain of linguistic

entities that morphology is different from sentence grammar since morphology

has the word domain as its focus.

This clear rejection of a level (‘module’) of morphology fits comfortably in the

American structuralist tradition rooted in Hockett’s ‘Item and Arrangement’ analysis

mentioned earlier, and continued more recently in the generative theory of Distributed

Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993). In this ‘morpheme-based syntax’,

morphological structure is simply syntactic structure within the word, so for example

the relation of the morphemes {cow} and {s} to the word ‘COW, plural’ is an

example of the same part:whole relation as the word’s relation to the phrase Cows

moo.

On the other hand, on page 15 Booij criticizes Goldberg 2006 for including

morphemes in a list of linguistic objects that are constructions (and praises her for

excluding them in a later publication):

... the category ‘morpheme’ should not appear on this list because morphemes

are not linguistic signs, i.e. independent pairings of form and meaning. The

minimal linguistic sign is the word, ...

This word-based view is much more compatible with the other main tradition in

morphology dating from Robins’s ‘Word and Paradigm’ analysis, the analysis of

traditional grammar and of many modern theoretical linguists (Aronoff 1994, Sadock

1991, Stump 2001, Anderson 1992); and even within cognitive linguistics it is

represented by both Neurocognitive Linguistics (Lamb 1998) and Word Grammar

(Hudson 2007). But if the minimal sign (or construction) is the word, and morphemes

are not constructions, it is hard to see how morphology can be ‘similar to sentence

grammar’.

Clearly there is some uncertainty in construction grammar about the status of

morphemes and morphological structure. On the one hand, constructions are claimed

to include ‘all grammatical knowledge’, so morphemes must be constructions; but on

the other hand, morphemes are claimed not to be constructions at all because they

have no intrinsic meaning. The question is important, especially as it involves a

fundamental hypothesis of construction grammar, so it deserves a great deal more

attention than it has received so far in the literature.

To make the issue more concrete, we return to our example Cows moo. In

morpheme-based syntax, the morphemes {cow} and {z} are units of syntax, so they

are combined by the same phrase-structure principles as the words ‘COW, plural’ and

‘MOO, present’. The same unity of treatment is implied by treating the morphemes as

constructions; so the morphemes {cow} and {z} constitute the parts of the

construction ‘COW, plural’, which in turn is a part of the entire sentence. In contrast,

word-based syntax treats the morphemes differently from the words. The words are

combined by syntax, and at least in phrase-structure analyses they are parts of larger

wholes. The morphemes, however, are not parts of the word ‘COW, plural’, but its

realization; in other words, they exist on a different level of abstraction, the level of

morphology. In morpheme-based syntax, therefore, there is a single level which

recognises both morphemes and words as its units (along with phrases), and combines

them all in the same kind of part:whole pattern; but in word-based syntax, there is a

level of syntax whose basic units are words, and there may be a different level of

morphology whose units are morphemes. In morpheme-based syntax, both words and

morphemes have a meaning and a phonological realization; but in word-based syntax,

words have a meaning but are realized by either morphology or phonology, and where

morphemes are recognised they have no meaning but do have a phonological

realization.

Section 3 argued that morphemes are cognitively real, so the question now is

whether they are related to words as parts, or as realizations. This issue has, of course,

been discussed extensively in the more general theoretical literature, but it is worth

considering whether cognitive linguistics has any special contribution to make to the

discussion. The experimental methods of cognitive psychology probably cannot throw

any light on the precise nature of the relationship between words and morphemes

beyond showing that they are distinct (as explained in section 3). However, cognitive

evidence is still relevant if, as cognitive linguists maintain, we use just the same

cognitive machinery for language as for other kinds of thinking.

The first relevant point is that general cognition recognises both of the

relations that we are considering as possibilities: part and realization. The part:whole

relation is ubiquitous in partonomies such as finger:hand:arm:body (where a finger is

part of a hand, which is part of an arm, which is part of a body). As for the linguist’s

realization relation, this is a special case of the relation between different construals

which exist on different levels of abstraction, such as the relation between an abstract

book and the paper on which it is printed, or between a chair seen as a seat or as a

collection of pieces of wood. The term ‘realization’ evokes the chain of abstractions

which become more ‘real’ as they become less abstract, resulting from the wellknown process of ‘representational redescription’ (Karmiloff-Smith 1992) by which

children’s minds progressively ‘redescribe’ experiences in increasingly abstract, and

potentially explicit, terms. In the case of a book or a chair, the concrete analysis of the

object is paired with a more abstract analysis in terms of its function, so the paper or

wood ‘realizes’ the book or chair. In language, an unit’s realization links it (directly or

indirectly) to the concrete reality of speech sounds (and marks).

Since both ‘part’ and ‘realization’ are availabe in our general cognitive

apparatus we could use either of them to relate the word to its morphemes. The choice

presumably depends on which of these two general relations fits the language patterns

most closely, so we can be guided by the facts of usage both as linguists and also as

language learners and users. How, then, can we distinguish parts from realizations?

The main differences involve abstractness and size. Parts exist on the same level of

abstraction as their whole, and are always smaller (Croft and Cruse 2004:151),

whereas realizations exist on a different level of abstraction, which means that sizes

are incomparable. In other words, the concepts must be different in some way, and

this difference may involve either size, or abstractness, but not both. For instance, a

book, seen at the most abstract level, has parts (chapters, sections and so on) which

exist at the same level; but it is realized by the paper on which it is printed, which

exists on a less abstract level and is measured by completely different criteria from the

abstract book. The abstract book and the concrete book are distinct concepts, with

quite different properties, and although each has a length, it is meaningless to ask

which is longer.

The size criterion will be important in the following argument, so it is worth

exploring a little further. Could a part be the same size as its whole? For instance,

consider the case of a one-piece swimsuit, whose name suggests it is a swim-suit with

just one part (called a ‘piece’). If this is so, then presumably the part is just the same

size as the whole; but in that case, how is the part different from the whole? Surely the

one ‘piece’ that constitutes the swimsuit is the swimsuit? The only reason for calling

it a one-piece swimsuit is to contrast it with a bikini, where each of the two parts is

clearly smaller than the whole. Without this contrast, there would be no more reason

for talking about a ‘one-piece swimsuit’ than about a one-piece towel, shirt or car.

The point of this example is to suggest that even when language suggests the

opposite, we do not in fact recognise a single part of a whole that has no other parts.

In short, nothing can have fewer than two parts.

Turning now to language, what is the relation between words and morphemes?

The crucial case to consider is not a bi-morphemic word such as cows, but a

monomorpheme such as cow or patient. Taking the the latter example, we have

already established that the morpheme {patient} is different not only from its

phonological realization, but also from both the noun PATIENTnoun and the adjective

PATIENTadj, so what is the relation between either of these words and the morpheme?

If it is the part:whole relation, there should be a difference of size; but the whole is

exactly the same size as its part. In syntactic terms, this is a commonplace example of

‘unary branching’, so one might assume that a monomorpheme is a word that has just

one morpheme as its part.

The trouble with this argument is that unary branching, even in syntax, is in

fact deeply problematic because it does not sit at all comfortably with the preceding

account of general cognition. It is such a fundamental part of mainstream linguistic

theory that it may be hard to imagine any alternative; but it has been called into

question not only by mainstream linguists (e.g. Chomsky 1995:246) but also by those

who work in the tradition of dependency grammar, which rejects phrase structure and

its related ideas including unary branching (e.g. Bröker 2001, Dikovsky and Modina

2000, Eades 2010, Eroms 2000, Gerdes and Kahane 2001, Hajicová 2000, Heringer

1996, Hudson 1984, Joshi and Rambow 2003, Kahane 2004, Kunze 1975, Mel'cuk

1988, Osborne 2006, Rambow and Joshi 1994, Sgall and others 1986, Tesnière 1959,

Venneman 1977). Given these two conflicting traditions in syntax, we cannot take the

notion of unary branching for granted; and indeed we have every reason to be

suspicious of it if it conflicts with our definition of ‘part’. How can a syntactic unit

have just one part which is on the same level of abstraction?

Unary branching is always presented as an innocent extension of the

part:whole relations on which phrase-structure analysis are based; but this is only

possible because of the primitive notation used in such analyses, which in turn was

based on the equally primitive mathematical notion of a ‘rewrite rule’. For example,

Figure 5 shows a fairly standard pair of trees for a rather conservative analysis of

surface structure in the spirit of Chomsky 1957. In this notation, trees log the

application of rewrite rules, and rewrite rules could be used to show very different

relationships. In this tree, the same notation is used to show that {cow} is part of

‘COW, plural’, that the latter is an example of ‘N’, and that /kaʊ/ realizes {cow} –

three very different relations sharing the same notation. The single lines of

classification and realization clearly act as a model for single parts, against the

evidence of logic and ordinary usage. The diagram for Stop!, where all the parts are

single, makes the point even more dramatically.

S

S

NP

VP

VP

N

V

V

COW, plural

MOO, present

STOP, imperative

{cow}

{z}

{moo}

{stop}

/kaʊ/

/z/

/mu:/

/stɒp/

Figure 5: Tree notation obscures relations

xxx

One way round this problem would be to let the relation depend on the

geometry of branching, so that unary branching indicates ‘realization’ and binary (or

higher) branching indicates ‘part’. In that case, V would be a part of VP when it has a

complement (as in eat grass) but the realization of VP when it has no complement.

But that would mean that V exists on the same level of abstraction as VP in the

former case, but on a different one in the latter – an absurd conclusion, so the

argument must contain a fault. The most plausible fault lies in the assumption that

unary branching is merely an innocent extension of phrase-structure grammar,

because this assumption conflicts with the general cognitive principle (discussed

above) that nothing can have only one part.

Suppose, then, that we rule out unary branching altogether. In that case we can

be sure that the morpheme {cow} is not a part of the word ‘COW, singular’, but its

realization. But if that is so, the same must be true for all other morphemes in relation

to their words; so the combination {cow} + {z}, which we might represent as

{{cow}{z}}, is the realization of the word ‘COW, plural’, and not its part or parts.

And in that case, morphology cannot be merely syntax within the word. In short, the

cognitive evidence supports the word-based theory of syntax in which morphemes are

the realizations of words rather than their parts. And in relation to construction

grammar, that means that morphemes are neither constructions nor parts of

constructions; so contrary to Croft’s claim, constructions do not provide a single

unified structure for all grammatical units.

On the other hand, it would be reasonable to object to this conclusion on the

grounds that unary branching is in fact allowed in constituency-based approaches to

syntax, including construction grammar, so the morpheme {cow} can be the only part

of the word ‘COW, singular’ in just the same way that the word ‘STOP, imperative’

can be the only part of its verb-phrase or clause. This is truly syntax within the word,

or morpheme-based syntax. The weakness of this defence, of course, is that the

cognitive objections to unary branching still apply; but the issue is now a much bigger

one: how satisfactory is constituency-based syntax when viewed from a cognitive

perspective? Can syntax involve unary branching when we don’t find this in ordinary

cognition? This is an important debate which should engage cognitive linguists, but

this article cannot pursue it any further.

5.

Do levels leak?

The cognitive evidence reviewed so far seems to have established that language is

organised on four levels:

semantic, with ordinary concepts such as people and events as units

syntax, with words and phrases as units

morphology, with morphemes (and, presumably, morpheme-clusters) as units

phonology, with phonemes and syllables as units.

(We might increase the list by distinguishing phonetics from phonology and by

expanding the media of language to include written language and signed language,

but these expansions are irrelevant to our present concerns.) This view of language

structure contrasts with the two levels of Cognitive Grammar and the three levels of

construction grammar.

In order to complete the picture of how language is organised, we need to

explore the relations among these levels, bearing in mind their cognitive basis in

human experience – in other words, taking a ‘usage-based’ approach. The main point

of cognitive linguistics is that the architecture is not imposed by our genetic make-up,

which somehow forces us to analyse language events on these four levels. Instead, it

claims that, given our general cognitive apparatus, we will eventually discover the

levels for ourselves in the usage to which we are exposed. This will not happen in one

fell swoop, but gradually. Our first analyses of language presumably associate barelyanalysed sounds directly with meanings or social situations, without any mediating

structures, and it is only gradually, as we analyse and sort out our experience, that we

recognise the need for further levels of structure. But we presumably only introduce

extra levels of organisation where they are helpful, which means that some ‘leakage’

remains, where levels are mixed. There is good evidence, both cognitive and

linguistic, that this is in fact the case.

The words of syntax, and their properties, are typically realized by morphemes

and morpheme clusters, as when ‘COW, plural’ is realized by {{cow}{z}}, but this is

not the only possibility. Word properties may also be realized directly by

phonological patterns within morphemes. This seems to be the case with syntactic

gender in French, where some phonological patterns are strong predictors of a noun’s

gender. For example, the phonological pattern /ezɔ̃/ written aison, as in maison

‘house’ and raison ‘reason’, is a good clue to feminine gender. Thanks to a classic

research project (Tucker and others 1977), we can be sure that both native speakers

and foreign learners are aware of this clue, albeit unconsciously. This linkage cannot

reasonably be reinterpreted as an example of morphological realization, with {aison}

as a morpheme, because the residue {m} or {r} is not a plausible morpheme and is

tightly bound to {aison}. Rather, the noun seems to be realized by a single morpheme,

with feminine gender realized by part of this morpheme’s phonology. This indicates a

direct linkage from phonology to syntax.

Similarly, part of a word’s phonology may be more or less strongly linked to

some aspect of its meaning. Such cases are called ‘phonesthemes’, and have been

shown to be cognitively real (Bergen 2004). For example, English words that start

with /gl/ are often related semantically to the idea of light and vision – glow, glimmer,

glitter, glare, glance, glimpse, glamour. Once again, a morphological division into

{gl} plus a residue is most implausible, and could only be justified by a theoretical

desire to avoid direct linkage from phonology to semantics.

As Booij observes, phonesthemes are not alone in relating phonology directly

to meaning, as the same can be said of the whole area of prosodic phonology,

including intonation (Booij 2010:11). For example, it is hard to see how a rising

intonation pattern spread across a number of words could be reduced to a single

morpheme within one of them.

Similar arguments suggest that a word’s realization may be partly

morphological, partly phonological. The most famous example is the word cranberry,

which gave its name to the ‘cranberry morpheme’ of American structuralism (Spencer

1991:40). The salient feature of this word is that it clearly contains the morpheme

{berry}, which is also found in other nouns such as blackberry and strawberry, but

the residue is not a plausible morpheme because it is not found in any other word.

Once again, the only reason for recognising the residue as a morpheme would be the

theoretical ‘purity’ of an analysis in which only morphemes can realize words. So far

as I know there is no relevant cognitive evidence, but if a relevant experiment could

be designed to test the cognitive reality of {cran}, one would predict a negative

outcome. In the absence of positive evidence, the only reasonable conclusion is that

the word CRANBERRY is realized by the phonological pattern /kran/ followed by the

morpheme {berry}.

The evidence suggests, therefore, that we can ‘skip’ levels by relating

phonological patterns directly to syntax or even semantics. In such cases, syntactic

units are realized by a mixture of two levels, phonology and morphology. More

generally, the examples surveyed illustrate a wide variety of patterns suggesting that

levels can ‘leak’ in any way imaginable, given the right functional pressures. Another

imaginable leakage is for morphemes to link directly to meanings, without going

through words; this is as predicted for all morphemes in morpheme-based syntax,

which I have rejected, but can we rule it out altogether? General cognitive theory

suggests that this should be possible, on the grounds that ‘any two nodes that fire

together, wire together’. As soon as we recognise a morpheme, its linkage to

meanings becomes relevant and may persist in memory even if it is also recorded as a

linkage between the meaning and the word containing the morpheme. For instance, if

the morpheme {man} (as in POLICEMAN, CHAIRMAN, etc) is always associated

with maleness, this association may be expected to appear in cognitive structure as a

direct link between {man} and ‘male’, even when we know that the person concerned

is female. Equally, it is obvious that we use some such link in interpreting neologisms

containing {man} such as BREADMAN; we hardly need experimental evidence for

this, but such evidence is available for our ability to interpret blends such as SMOG

(built out of {smoke} and {fog} - Lehrer 2003).

The picture that emerges from this discussion is rather different from the

familiar neat level diagrams in which each level is related directly only to the levels

on either side of it. The levels can still be ordered hierarchically in terms of increasing

abstractness: phonology – morphology – syntax – semantics; and the neat diagrams

are still accurate descriptions of the typical arrangement. But we have seen that the

levels are in fact a great deal more interconnected than these diagrams allow. Instead

of a list of levels, we have a network, as shown in Figure 6. This is very much more

plausible as a model of a system which has evolved, both in the individual and in the

community, by abstracting patterns from millions of examples of interaction in usage.

meaning

syntax

morphology

phonology

Figure 6: Unconstrained links between levels

6.

Which theory?

If language really is organised into levels along the lines suggested in Figure 6, then

we should expect any theory of language structure not only to allow this kind of

organisation, but even to explain it. This concern with architecture is, of course, only

one part of any general theory of language, and cognitive theories of language include

a great many important insights which are not affected by their success or otherwise

in handling the architectural issues – ideas such as entrenchment, embodiment and

construal.

It is hard to evaluate other people’s theoretical packages in relation to an issue

which does not interest them, so I will not try to determine whether the well-known

cognitive theories such as Cognitive Grammar or the various versions of construction

grammar (Croft and Cruse 2004) are compatible with this view of language

architecture. The dangers became clear in section 2, where I argued against

Langacker’s claim that all units of language are symbolic units with a semantic and a

phonological pole, only to note later that he actually recognises symbolic units

without a semantic pole.

Similarly, I mentioned the claim which Croft describes as ‘one of the

fundamental hypotheses of construction grammar: there is a uniform representation of

all grammatical knowledge in the speakers’s mind in the form of generalized

constructions’ (Croft 2007:471). According to Croft, the ‘syntax-lexicon continuum’

includes syntax, idioms, morphology, syntactic categories and words. This

generalisation applies to Cognitive Grammar as well as construction grammar: ‘the

only difference between morphology and syntax resides in whether the composite

phonological structure ... is smaller or larger than a word.’ (Langacker 1990:293).

This claim appears to exclude the possibility of a division between syntax and

morphology, and yet I also noted that Booij’s Construction Morphology believes that

this view can be reconciled with the view that morphemes are not ‘linguistic signs, i.e.

independent pairings of form and meaning’. While the defenders of a theory show this

degree of uncertainty and openness it is neither fair nor useful for outsiders to

speculate about what the theory ‘really’ allows.

Unlike other cognitive theories, Word Grammar explicitly rejects the idea that

all language units are inherently and essentially symbolic, with direct links to both

meaning and form. This theory takes a much more traditional position on the levels of

language, with two levels (morphology and syntax) mediating between phonology

and semantics. In this theory, there are no constructions (if constructions are defined

as a pairing of a meaning with a phonological form) because typical words have a

meaning but no phonology, and morphemes have a phonological form but no

meaning. Moreover, the general theory of category-construction which is part of

Word Grammar predicts that both words and morphemes will emerge in the learner’s

mind because of the way in which categories are induced from experience (Hudson

2007:72-81).

However, published discussions of Word Grammar have also presented too

simple a picture of the relations between levels. So far Word Grammar has only

recognised links between adjacent levels, but section 5 showed that links may skip

levels. Fortunately, the default inheritance logic which is central to Word Grammar

allows the theory to accommodate these exceptions, and even to predict them, as I

now explain.

Word Grammar analyses language as a gigantic network, so I must first

explain how it distinguishes and relates levels. Each level is characterised by a

particular kind of unit: words and word-combinations in syntax, morphemes and

morpheme-combinations in morphology, and phonemes and phoneme-combinations

in phonology. This means that each level is built round a prototypical item (the

prototypical word, morpheme or phoneme) whose properties are inherited by all

examples – but only by default, so exceptions are possible. Among these properties

are the item’s relations to items on other levels, so the typical word has a meaning (on

the level of semantics) and is realized by the typical morpheme, which in turn is

realized by the typical phoneme (or, more probably, by the typical syllable). The

differences between levels are thus built into the definitions of the units concerned, as

also are the relations between levels.

This set of default linkages defines the typical inter-level links, but the logic of

default inheritance allows exceptions, and indeed, since exceptions are so prevalent in

language, it would be surprising if there were none in such an abstract area of the

mind. For example, even if typical morphemes have no meaning, nothing prevents

some morphemes from having meanings which may even differ from those of the

words they realize (as in the case of chairman). Similarly, even if words are typically

realized by morphemes, some may share the phonological realization of the

morphemes that realize them (as well as extra phonemes such as the cran of

cranberry).

7.

Conclusions

The very least that we can conclude from this discussion is that the assumptions of

cognitive linguistics are relevant to some of the major issues that theoretical linguists

confront concerning the overall architecture of language. If language really is an

ordinary part of general cognition, as cognitive linguists maintain, then we can expect

cognitive science to throw light on these big questions; or, putting it less

dogmatically, if we want to test the hypothesis that language is ordinary cognition,

then we must try hard to build architectural models that are compatible with the

findings of cognitive science. This project is very much in line with the goals of

cognitive linguistics, but the debate has hardly begun.

The main purpose of this article has been to present a cognitive case for a

rather conservative four-level analysis of language in which both morphology and

syntax mediate between phonology (or graphology) and meaning. It is comforting that

the cognitive evidence leads to much the same conclusion as more traditionally

‘linguistic’ arguments based on notions such as generality and simplicity. However, if

this conclusion is correct it seriously undermines the widespread assumption that the

principles of cognitive linguistics somehow lead inevitably to a view of language

architecture which is essentially symbolic, with phonological form directly linked to

meaning in every unit of analysis. In short, this article questions the central role that

most cognitive theories assign to the notion ‘symbolic unit’ or ‘construction’.

To be clear about what is at stake, there is no suggestion here that ‘rules’ form

a different level, less still a different module, from ‘the lexicon’. The lexicogrammatical continuum is not threatened by any of the evidence presented here, so

long as it is simply a matter of generality (with general ‘rules’ or schemas at one end

and specific items at the other). Nor do I doubt that our lexico-grammatical continuum

includes a vast amount of tiny detail based on observed usage, nor that different items

of knowledge have different degrees of entrenchment. And above all, I accept that

language is a declarative conceptual network, without modules or other extrinsically

imposed boundaries.

The discussion here defines some of the parameters for any theory of language

structure rather than the claims of any one theory. On the other hand, I have also

suggested that Word Grammar already fits most of these parameters, although it needs

some further work in the area of level-skipping.

References

Anderson, Stephen 1992. A-morphous morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Aronoff, Mark 1994. Morphology by Itself. Stems and inflectional classes.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Bauer, Laurie 2006. 'Folk Etymology', in Keith Brown (ed.) Encyclopedia of

Language & Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier, pp.520-521.

Bergen, Benjamin 2004. 'The psychological reality of phonaesthemes.', Language 80:

290-311.

Bock, Kathryn, Dell, Gary, Chang, Franklin, and Onishi, Kristine 2007. 'Persistent

structural priming from language comprehension to language production',

Cognition 104: 437-458.

Bolte, J. and Coenen, E. 2002. 'Is phonological information mapped onto semantic

information in a one-to-one manner?', Brain and Language 81: 384-397.

Booij, Geert 2010. Construction Morphology. Oxford University Press

Branigan, Holly 2007. 'Syntactic Priming', Language and Linguistics Compass 1: 116.

Bröker, Norbert 2001. 'Formal foundations of dependency grammar', in Vilmos Ágel

(ed.) Dependency and Valency. An International Handbook of Contemporary

Research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp.

Chomsky, Noam 1957. Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton

Chomsky, Noam 1995. 'Categories and Transformations. ', in Noam Chomsky (ed.)

The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, pp.219-394.

Croft, William 2007. 'Construction grammar', in Dirk Geeraerts & Hubert Cuyckens

(eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford

Univesity Press, pp.463-508.

Croft, William and Cruse, Alan 2004. Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge University

Press

Dikovsky, Alexander and Modina, Larissa 2000. 'Dependencies on the other side of

the curtain', Traitement Automatique Des Langues 41: 79-111.

Eades, Domenyk 2010. 'Dependency grammar', in Kees Versteegh (ed.) Encyclopedia

of Arabic Language and Linguistics Online. Leiden: Brill, pp.

Eroms, H. W. 2000. Syntax der deutschen Sprache. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Evans, Vyvyan and Green, Melanie 2006. Cognitive Linguistics. An introduction.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Fiorentino, Robert and Fund-Reznicek, Ella 2009. 'Masked morphological priming of

compound constituents', The Mental Lexicon 4: 159-193.

Fodor, Jerry 1983. The Modularity of the Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Frost, Ram, Deutsch, Avital, Gilboa, Orna, Tannenbaum, Michael, and MarslenWilson, William 2000. 'Morphological priming: Dissociation of phonological,

semantic, and morphological factors', Memory & Cognition 28: 1277-1288.

Frost, Ram., Ahissar, M., Gotesman, R., and Tayeb, S. 2003. 'Are phonological

effects fragile? The effect of luminance and exposure duration on form

priming and phonological priming', Journal of Memory and Language 48:

346-378.

Gerdes, Kim and Kahane, Sylvain (2001). word order in german: a formal

dependency grammar using a topological hierarchy.Anon.

Goldberg, Adele 2006. Constructions at work. The nature of generalization in

language. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Guy, Greg 1980. 'Variation in the group and the individual: the case of final stop

deletion', in Anon. Locating Language in Time and Space. London: Academic

Press, pp.1-36.

Guy, Greg 1991a. 'Contextual conditioning in variable lexical phonology', Language

Variation and Change 3: 239

Guy, Greg 1991b. 'Explanation in variable phonology: An exponential model of

morphological constraints', Language Variation and Change 3: 1-22.

Guy, Greg 1994. 'The phonology of variation', Chicago Linguistics Society

Parasession 30: 133-149.

Guy, Greg and Boyd, Sally 1990. 'The development of a morphological class.',

Language Variation and Change 2: 1-18.

Hajicová, Eva 2000. 'Dependency-based underlying-structure tagging of a very large

Czech corpus.', Traitement Automatique Des Langues 41: 57-78.

Halle, Morris and Marantz, Alec 1993. 'Distributed morphology and the pieces of

inflection.', in Ken Hale & Samuel Keyser (eds.) The view from Building 20:

essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, pp.111-176.

Harley, Trevor 1995. The Psychology of Language. Hove: Psychology Press

Heringer, H. J. 1996. Deutsche Syntax dependentiell. Tübingen: Stauffenburg

(=Stauffenburg Linguistik)

Hockett, Charles 1958. 'Two models of grammatical description', in Martin Joos (ed.)

Readings in Linguistics, 2nd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

pp.386-399.

Hudson, Richard 1984. Word Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hudson, Richard 1990. English Word Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hudson, Richard 1997. 'Inherent variability and linguistic theory', Cognitive

Linguistics 8: 73-108.

Hudson, Richard 2007. Language networks: the new Word Grammar. Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Hudson, Richard 2010. An Introduction to Word Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Hudson, Richard and Holmes, Jasper 2000. 'Re-cycling in the Encyclopedia', in Bert

Peeters (ed.) The Lexicon/Encyclopedia Interface. Amsterdam: Elsevier,

pp.259-290.

Hutchison, Keith 2003. 'Is semantic priming due to association strength or feature

overlap? A microanalytic review.', Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 10: 785813.

Joshi, Aravind and Rambow, Owen 2003. 'A Formalism for Dependency Grammar

Based on Tree Adjoining Grammar.', in Sylvain Kahane & Alexis Nasr (eds.)

Proceedings of the First International Conference on Meaning-Text Theory.

Paris: Ecole Normale Supérieure, pp.

Kahane, Sylvain 2004. 'The Meaning-Text Theory', in Vilmos Àgel, Ludwig

Eichinger, Hans-Werner Eroms, Peter Hellwig, Hans-Jürgen Heringer, &

Henning Lobin (eds.) Dependency and Valency. An International Handbook of

Contemporary Research. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp.

Karmiloff-Smith, Annette 1992. Beyond Modularity. A developmental perspective on

cognitive science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Kunze, Jürgen 1975. Abhängigkeitsgrammatik. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag

Lamb, Sydney 1966. Outline of Stratificational Grammar. Washington, DC:

Georgetown University Press

Lamb, Sydney 1998. Pathways of the Brain. The neurocognitive basis of language.

Amsterdam: Benjamins

Langacker, Ronald 1990. Concept, Image and Symbol. The Cognitive Basis of

Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter

Langacker, Ronald 2007. 'Cognitive grammar', in Dirk Geeraerts & Hubert Cuyckens

(eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, pp.421-462.

Lehrer, Adrienne 2003. 'Understanding trendy neologisms', Italian Journal of

Linguistics - Rivista Linguistica 15: 369-382.

Marslen-Wilson, William 2006. 'Morphology and Language Processing', in Keith

Brown (ed.) Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Second edition. Oxford:

Elsevier, pp.295-300.

Mel'cuk, Igor 1988. Dependency syntax : theory and practice. Albany: State

University Press of New York

Osborne, Timothy 2006. 'Beyond the Constituent - A Dependency Grammar Analysis

of Chains', Folia Linguistica 39: 251-297.

Partridge, Eric 1966. Origins. An etymological dictionary of the English language

(fourth edition). London: Routledge

Rambow, Owen and Joshi, Aravind 1994. 'A Formal Look at Dependency Grammars

and Phrase-StructureGrammars, with Special Consideration of Word-Order

Phenomena.', in Leo Waner (ed.) Current Issues in Meaning-Text Theory.

London: Pinter, pp.

Reisberg, Daniel 2007. Cognition. Exploring the Science of the Mind. Third media

edition. New York: Norton

Robins, Robert 1959. 'In Defence of WP (Reprinted in 2001 from TPHS, 1959)',

Transactions of the Philological Society 99: 114-144.

Sadock, Jerrold 1991. Autolexical Syntax: A theory of parallel grammatical

representations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Sgall, Petr, Hajicová, Eva, and Panevova, Jarmila 1986. The Meaning of the Sentence

in its Semantic and Pragmatic Aspects. Prague: Academia

Spencer, Andrew 1991. Morphological Theory. Oxford: Blackwell

Stemberger, Joseph 1998. 'Morphology in language production with special reference

to connectionism', in Andrew Spencer & Arnold Zwicky (eds.) The Handbook

of Morphology. Oxford: Blackwell, pp.428-452.

Stump, Gregory 2001. Inflectional Morphology: A Theory of Paradigm Structure.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Stump, Gregory 2006. 'Paradigm Function Morphology', in Editor-in-Chief:-á-á Keith

Brown (ed.) Encyclopedia of Language &amp; Linguistics (Second Edition).

Oxford: Elsevier, pp.171-173.

Tesnière, Lucien 1959. Éléments de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck

Tucker, G. R., Lambert, Wallace, and Rigault, André 1977. The French speaker's skill

with grammatical gender: an example of rule-governed behavior. The Hague:

Mouton

Venneman, Theo 1977. 'Konstituenz und Dependenz in einigen neueren

Grammatiktheorien', Sprachwissenshaften 2: 259-301.