Civil Service Reform: - University of Dayton

R

ADICAL

C

IVIL

S

ERVICE

R

EFORM IN THE

U

NITED

S

TATES

:

A T EN -Y EAR R ETROSPECTIVE

STEPHEN E. CONDREY

The University of Georgia, USA condrey@cviog.uga.edu

R. PAUL BATTAGLIO, JR.

University of Nevada, Las Vegas paul.battaglio@unlv.edu

Prepared for “Public Administration in the XXI Century: Traditions and Innovations,”

Lomonosov Moscow State University School of Public Administration

Moscow, Russia

May 24-26, 2006

WORKING DRAFT – Not for release or citation without the express permission of the authors.

Abstract

Despite widespread predictions of a return to spoils politics, radical civil service reform continues to diffuse to units of government across the United States with little adverse effects. Utilizing a survey of state human resources professionals, a review of the literature, as well as a general population survey, the authors suggest five plausible explanations for the diffusion of at-will employment policies. In particular, the authors posit that the changing relationship of elective politics and public employment has diminished the importance of civil service protections in large, bureaucratic organizations.

Authors’ Note: The authors are grateful for the research assistance of Ilka Decker of the Carl Vinson Institute of

Government in preparing and conducting research for this article. The authors are also grateful to those who gave of their time to respond to the surveys and to provide information related to writing this article.

- 2 -

Radical Civil Service Reform in the United States: A Ten-Year Retrospective

One thing seems clear: that the principles of merit and the practices whereby they were given substance are changing and must change a good deal more to remain viable in our society.

Frederick C. Mosher

Democracy in the Public Service

(1982, p. 221)

In 1996, the State of Georgia abolished job protections for newly hired state employees. This radical reform has since diffused in some fashion to a number of other states and units of government in the United States. This paper will provide a ten-year retrospective analysis of the Georgia reform, drawing lessons from the Georgia experience for public organizations in the United States as well as other countries. The analysis will utilize historical research, selected interviews, surveys of human resource management professionals, and a state-wide general population survey of citizen attitudes toward at-will employment.

This paper reports the results from two surveys conducted by the authors from

January to March 2006. The first survey conducted was of State of Georgia human resource professionals (274 respondents; 51.3% response rate). The second was a poll of the general population of the State of Georgia (805 respondents; 95% confidence interval). Additionally, the authors draw upon similar survey research studies conducted in 2005 and 2006 in the States of Florida and Texas and concerning at-will employment in those states.

Radical Civil Service Reform in the United States

It has been ten years since Georgia implemented radical civil service reform. In essence, the Georgia reform legislation abolished civil service protections for newly-

- 3 -

hired employees as well as those accepting promotions or transfers to other positions in state government. As of 2006, approximately 76% of State of Georgia employees are employed at-will (State of Georgia, Georgia Merit System, personal correspondence,

March 30, 2006).

The Georgia experiment has garnered considerable interest among human resource management scholars in the United States. To attest to this, two entire issues of the Review of Public Personnel Administration , the leading public human resource management journal in the United States, have been devoted to civil service reform

( Review of Public Personnel Administration , Summer 2002; Summer 2006).

Radical civil service reform is couched in the tenets of New Public Management.

New Public Management advocates espouse freeing managers from the bonds of bureaucratic constraint to allow them to effectively manage their organizations. Effective government, proponents contend, will result from reducing or limiting the role of government with a clear preference for private sector models of productivity and management (Kettl, 2000; Savas, 2000). This ideology views civil service protections as a hindrance to good management; radical reform would allow more efficient government, albeit without a check on managerial excesses. Hence, the State of Georgia was looked upon by many as a model for modernizing civil service systems. Writing in 2002,

Condrey noted that:

It is too early to see if cronyism, favoritism, and unequal pay for equal work with be the wholesale result of the Georgia reform. However, in this author’s view, the likelihood of these problems occurring has increased due to the diminished role of Georgia’s central personnel authority. As other states look at Georgia, it is hoped that they will work to devise strategic

- 4 -

partnerships between central and agency personnel authorities, seeking a healthy balance between responsiveness and continuity (p. 123).

The following analysis will begin to answer the questions above concerning the State of

Georgia reform as well as the effects of the diffusion of at-will employment policies to other state governments.

A View from the States

Hays and Sowa surveyed all fifty states to determine whether at-will employment policies were expanding and whether or not decentralization of the human resource function was taking place (2006). Table 1 reports their results.

Table 1: General Summary of Interview Findings: Snapshot of Current Conditions in the States’

Personnel Systems

State Level of Human

Resources

Decentralization

Expansion of At-Will

Employees

Range of Grievable

Issues

Activist

Governor

"Decline in Job

Security"

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Partial

Centralized

Partial

Significant

Partial

Significant

Partial

Partial

Significant

Significant

Centralized

Partial

Partial

Recentralizing

Significant

Significant

Centralized

Partial

Recentralizing

Partial

Partial

Partial

No

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

Agency specific

Restricted

Restricted

Restricted, agency specific

Expansive

Restricted

Expansive

Expansive

Restricted

Restricted

Expansive

Agency specific

Expansive

Restrictive

Expansive

Expansive, agency specific

Expansive

Restricted

Expansive

Expansive

Expansive

Expansive

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

- 5 -

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Partial

Partial

Significant

Partial

Centralized

Partial

Partial

Partial

Centralized

Partial

Significant

Significant

Partial

Significant

Partial

Significant

Centralized

Significant

Centralized

Centralized

Complete

Partial

Significant

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Expansive

Restricted

Agency specific

Restricted

Restricted

Expansive

Expansive

Expansive

Expansive

Expansive

Restricted

Restricted

Restricted

Restricted

Expansive

Expansive

Expansive, but not utilized

Restricted

Expansive

Restricted

Not applicable

Expansive

Restricted

No

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Significant

Significant

Partial

Partial

No

Yes

Yes

No

Restricted

Restricted

Restricted

Expansive

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Wyoming Partial

(Source: Hays & Sowa, 2006)

Yes Restricted No No

As can be clearly seen from the results in Table 1, at-will employment influences

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

No have diffused to a majority of state governments (28 states; 56%). Additionally, of the twenty-eight state governments reporting at-will policy expansion, twenty-five (89%) also report some degree of decentralization of their personnel systems. The logical result of this decentralized, at-will environment is agency-specific, manager-centered human resource systems: a much different scenario than the centralized, rule-oriented systems they replaced. This result appears particularly salient for those states with weak employee unions and collective bargaining rights.

- 6 -

In addition to Georgia, two other states have been at the forefront in the evolution

(or revolution) to at-will employment: Texas and Florida. Coggburn reports that the State of Texas has long operated in a decentralized, at-will human resources environment

(2006). Because of the maturity of the management structure in Texas state government,

Coggburn observes that the state’s organizational culture has managed to avoid the wholesale cronyism that one might expect would result from the abolition of employment rights. Fully 97.4% of state human resource directors surveyed agreed that “even though employment is at-will, most employee terminations are for good cause” (Coggburn, 2006, p. 166).

James Bowman and Jonathan West have examined the Florida experience (2006).

Florida Governor Jeb Bush, is the brother of current United States President and former

Governor of Texas George W. Bush. Florida’s Service First program, approved by the

Florida Legislature in 2001, has placed a large number of senior state government managers in at-will status. Additionally, through its People First initiative, Florida has chosen to outsource much of its human resource function. Bowman and West note that this managerialist view of government is eroding the traditional role of governmental human resource management:

…the management of human resources is undergoing profound transition in concept and practice.

A key component of this transformation is the dissolution of the traditional social contract at work: job security with good pay and benefits in exchange for employee commitment and loyalty. In the process, the longstanding American employment at-will doctrine, which was eroded in the latter part of the 20 th century, has been revitalized and has spread to the public sector through civil service reform (2006, p. 139).

- 7 -

Florida’s reform has been more controversial than reform in other states.

Convergys, the firm to which many routine human resource processing functions was outsourced, experienced delays and “significant problems…as they became operational,” including payroll and benefit errors (OPPAGA, 2006, p.2). While touted to save the government of the State of Florida an average of $24.7 million annually, the state has yet to establish “a methodology to capture project cost savings” (OPPAGA, 2006, p.3).

In summarizing the first five years of the Service First initiative in Florida,

Bowman and West report that state officials found the reforms to be “of little consequence at best and harmful at worst” (2006, p.155). This was in contrast to the overall opinion of state human resource directors that held a more “sanguine view” of the reform, citing some administrative improvements (2006, p.155).

While the jury is still out on the long-term effects of radical civil service reform, at-will employment, decentralization, and in some cases, outsourcing of the human resources function, the preceding pages demonstrate that these trends are diffusing to other states as well as to other levels of government in the United States. The following sections will discuss the methodology of the current study, present the results of the

Georgia state human resources professionals and general population surveys, compare summary results of the Georgia human resources professionals survey with those of three other states, and draw implications for the practice of human resources management both in the United States and abroad.

- 8 -

Methodology and Analysis

Data

The data utilized in this analysis were obtained from a mail survey of State of

Georgia human resources professionals. As detailed above, the Georgia reforms have changed the framework for the delivery of human resources services to state employees.

A significant amount of authority for the delivery of not only services to the public but also the delivery of public human resources management to state employees has been decentralized and delegated to state agencies.

As a result, state agency HR professionals are in a unique position to assess the overall efficiency and effectiveness of these reforms. Their expertise and responsibilities in the area of public employment in the state gives them an advantage in assessing the impact of at-will employment in Georgia government. An analysis of their survey responses will provide scholars and practitioners a compelling depiction of the status of at-will employment in the state.

The survey was conducted by the authors during a three month period from

January to March 2006 following the total design method for mail surveys (Dillman,

1978). The surveys were mailed to 534 Georgia human resources professionals whose names were obtained from the State of Georgia’s central file of those responsible for administering state human resource management activities. A follow-up survey mailing resulted in a total survey return rate of approximately 51.3 percent, or 274 completed surveys.

The survey asked respondents to indicate their level of agreement with a number of statements related to at-will employment in the state of Georgia. A copy of the survey

- 9 -

is presented in Appendix A. The first eighteen survey items were statements intended to obtain respondents’ views of at-will employment in general. The next twenty-nine statements elicited respondents’ attitudes based on their experiences with at-will employment in their respective agencies.

Finally, the survey included questions regarding respondent demographics and characteristics of the respondent’s employing agency. Demographic questions included the respondent’s age range, gender, race/ethnicity, political views, previous HR private sector experience, years of service in the public sector, years of service in the HR field, educational level, and HR-related professional designations. Information collected regarding agency characteristics included the percentage of at-will employees in the agency and the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees in the agency.

Regression analysis was utilized to extract a thorough understanding of state HR professionals’ attitudes toward at-will employment. Demographic and agency-specific characteristics were employed as independent variables in the analysis. Several scales were developed using the statements on general and agency-specific sentiment. The discussion below first details the scale development of the dependent variables for use in the regressions and then discusses the implications from the regression analysis.

The Dependent Variables

The dependent variables utilized in this analysis are scales developed from the statements in the survey instrument. Using a theoretical construct, scales were developed with survey items from the respondents’ views on at-will employment in general. These scales reflect respondent attitudes toward theoretical policy intentions and effects of atwill employment (DeVellis, 2003).

These theories are associated with potential

- 10 -

implications of civil service reform covered in the literature (Battaglio & Condrey, 2006;

Kellough & Nigro, 2006; Condrey, 2002). Potential implications include the notion that many of these managerial reforms will result in more accountable government, public management reform initiatives associated with New Public Management (NPM), and greater discretion in the dismissal of employees. The statements from the survey employed in the scale development for the dependent variables are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2: Survey Statements Utilized in Scale Development for Dependent

Variables

In GENERAL, at-will employment in government. . .

(Coded 1 = “Strongly Disagree” and 5 = “Strongly Agree”)

1.

Leads to greater customer satisfaction for citizens.

2.

Leads to greater government accountability and responsiveness to the public.

3.

Has streamlined the hiring/firing process.

4.

Helps ensure employees are responsive to the goals and priorities of agency administrators.

5.

Provides needed motivation for employee performance.

6.

Makes the HR function more efficient.

7.

Provides essential managerial flexibility over the HR function.

8.

Represents an essential piece of modern government management.

9.

Makes employees feel more secure about their jobs.

10.

Discourages employees from taking risks that could lead to program or policy innovation.

11.

Discourages employees from reporting agency wrongdoing (or “blowing the whistle”).

12.

Discourages employees from freely voicing objections to management directives.

13.

Could—by not requiring a rationale or justification for terminating employees— negatively affect managers’ decision-making in other non-HR decisions.

14.

Could—by not requiring a rationale or justification for terminating employees—make public employees less sensitive to issues of procedural fairness.

15.

Is at odds with the public sector’s traditional emphasis on merit in human resources decisions.

16.

Makes state government jobs less attractive to current and future employees than would be the case if there was more job security.

17.

Gives an upper-hand to employers relative to employees in the employment relationship.

18.

Is sometimes used to fire competent employees so other people with friends or connections to government can be hired.

- 11 -

The first dependent variable is a scale developed from perceptions that at-will employment discourages responsible government. Scholarship suggests that the uneasiness associated with at-will employment in Georgia is not unfounded, given the potential for political abuse and normative implications for removing traditional public sector employee protections (Battaglio & Condrey, 2006; Condrey, 2002; Gossett, 2002).

The “Discourages Good Government” scale was calculated by summing responses for four statements (statements 10-12 and 16) from the survey; higher values are associated with stronger levels of agreement. These statements were worded and coded so that a higher value on the scale corresponds to a more negative sentiment toward at-will employment and an increasing belief that at-will employment discourages good government. The scale has a respectable degree of internal reliability, indicated by a

Cronbach’s alpha of .784.

The next dependent variable is a scale developed from survey statements indicating that at-will employment upholds certain tenets of New Public Management

(NPM). The literature identifies forces at work in promoting a managerialist ideology in public sector governance, including notions of efficiency, accountability, responsiveness, customer satisfaction, motivation, managerial flexibility, performance, streamlining, and modern management (Kettl, 2000; Savas, 2000). The “Supports NPM Principles” scale was developed by summing responses to survey statements 1-8, where higher values are associated with stronger levels of agreement. These statements were worded and coded so that a higher value on the scale corresponds to a more positive view of at-will employment. A Cronbach’s alpha of .893 indicates a high degree of internal reliability for this scale.

- 12 -

A final dependent variable was constructed through a scale of survey statements signifying at-will employment resulted in dubious dismissals. The public personnel literature underscores the potential for arbitrary dismissals to result from the Georgia reforms (Battaglio & Condrey, 2006; Condrey, 2002; Gossett, 2002). The “Encourages

Dubious Dismissals” scale was calculated by summing responses for five statements

(statements 13 – 15, 17, and 18) from the survey, where higher values are associated with stronger levels of agreement. These statements were worded and coded so that a higher value on the scale corresponds to a more negative sentiment about at-will employment.

In other words, a high scale value indicates a belief that at-will employment increases the likelihood that organizational dismissals based on questionable criteria take place. This scale also has a respectable degree of internal reliability, indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha of .801.

Findings

The findings from employing the three dependent variables in the regression model are detailed in Tables 3. With respect to respondent experience and the percentage of employees serving at-will, the results are interesting. Respondents who have a longer tenure in their positions (Age and Years in Service 1 ) consistently tend to view at-will employment in Georgia as discouraging good government, not espousing the tenets of

NPM, and having the potential to result in arbitrary dismissals. The findings suggest that seasoned public sector HR veterans have seen management fads come and go with very little overall effectiveness. They also appear wary of increased managerial discretion coupled with diminished employee protections.

1 To measure tenure in office, the variables for age and years of service in the public sector were combined, and computed into a new variable, Age and Years in Service. This variable was coded 1=16 or more years in service and 45 and older; 0=15 or less years in service and 44 and younger.

- 13 -

T

ABLE

3: Impact of Agency-Specific Experiences on General

Scales for Attitudes toward At-Will Employment

Discourages

Good

Government

Supports NPM

Principles

Encourages

Dubious

Dismissals

I

NDEPENDENT

V ARIABLES

Age and Years in Service

Prior Private

Sector

Experience

Percentage of

Employees

Serving At-Will

Gender

Education

Left

Right

Caucasian

Political Views –

Political Views –

African

American

Misuse of the

HR System

Unwarranted

RIFs

Trust

Management

R-Squared

.211**

(1.99)

.146

(1.23)

.001

(0.05)

-.383**

(-2.71)

-.091**

(-1.97)

-.148

(-1.02)

.036

(0.33)

-.180

(-0.66)

-.096

(-0.34)

.133*

(1.82

.062

(1.05)

-.444**

(-5.31)

-.0545*

(-0.55)

.038

(0.34)

.006**

(2.64)

.185

(1.40)

.014

(0.32)

.020

(0.15)

.045

(0.44)

-.264

(-1.03)

-.435*

(-1.63)

-.002

(-0.04)

-.043

(-0.78)

.344**

(4.41)

.306 .184

Column entries include regression coefficients and t-scores in parentheses.

.161*

(1.91)

.190**

(2.01)

.003

(1.35)

.007

(0.06)

-.004

(-0.10)

-.180

(-1.56)

-.013

(-0.14)

.069

(0.32)

.139

(0.61)

.278**

(4.79)

.055

(1.16)

-.457**

(-6.89)

.503

N = 232 (cases with missing data were dropped from the regression)

**Significant at the .05 level

*Significant at the .10 level

For respondents with prior experience in the private sector (coded 1=Yes; 0=No), the expectation is for a tendency to view at-will employment favorably. Interestingly,

- 14 -

statistical significance is only achieved for one of the dependent variables, “Encourages

Dubious Dismissals.” Contrary to expectations, this finding suggests respondents may be more savvy and less trusting of an at-will environment as a result of their previous private sector experience.

Additionally, the variable for percentage of agency employees that are at-will is statistically significant at the .10 level for “Supports NPM Principles.” Thus, it appears that HR professionals in agencies with a high percentage of at-will employees may have bought into the managerialist ideology promulgated by the Georgia reformers.

Demographic characteristics are significant predictors for the variables “Supports

NPM Principles” and “Discourages Good Government.” At the .10 significance level, female respondents perceive that at-will employment discourages good government.

Educational level (coded 1=high school diploma; 2=2 year college degree; 3=4 year college degree; 4=master’s degree; 5=law degree; and 6=Ph.D. or equivalent) is also statistically significant at the .10 level in the case of “Discourages Good Government."

Respondents achieving higher levels of education do not agree that at-will employment discourages good government. With respect to race/ethnicity, African-American respondents demonstrated marginal statistical significance (.105) for the “Supports NPM

Principles” dependent variable. It would appear African-American respondents do not agree that at-will employment upholds the tenets of NPM, such as a more responsive and motivated workforce.

The model also tested respondents’ political views. The expectation is that respondents who tend to align themselves to the left of the political spectrum would favor a stronger role for government. Therefore, the hypothesis is that respondents aligned to

- 15 -

the left are opposed to the idea of public sector at-will employment. However, the “Left” coefficient is not in the correct direction, and falls short of the .10 significance level for all three dependent variables.

Conversely, respondents who align themselves to the right of the political spectrum should favor a stronger role for private sector managerialism in government.

Thus, the hypothesis is that respondents who align themselves to the right are in favor of at-will employment. Yet, the “Right” coefficient, while in the correct direction for

“Supports NPM Principles” and “Encourages Dubious Dismissals,” is in the wrong direction for “Discourages Good Government" and does not achieve statistical significance for the three dependent variables. Interestingly, it would appear that political ideology has little influence in how these reforms are viewed by respondents.

Finally, the last three independent variables in Table 3, “Misuse of the HR

System,” “Unwarranted Reductions in Force (RIFs),” and “Trust in Management,” test whether agency-specific experiences are a significant predictor of respondent opinions towards at-will employment. Once again, scale development was utilized in the model for the development of the agency-related variables. For all three variables, scales were calculated by summing agency-specific responses for survey statements, where higher values are associated with stronger levels of agreement.

The scales for “Misuse of the HR System” and “Unwarranted RIFs” presume that at-will employment may lead to misuses in the personnel process and unwarranted reductions in force. These statements were worded and coded so that a higher value on the scale corresponds to a more negative sentiment about at-will employment. The scales

- 16 -

have a high degree of internal reliability indicated by their respective Cronbach’s alphas of .823 and .864.

The “Trust in Management” statements were associated with whether or not HR professionals trust their supervisors to do the right thing in personnel matters. These statements were worded and coded so that a higher value on the scale corresponds to a more positive view of at-will employment. The scale has a respectable degree of internal reliability, indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha of .777.

The findings from the regression with respect to the agency-specific scales prove to be respectable. “Misuse of the HR System” achieves statistical significance in the case of “Discourages Good Government” (.10 level) and “Encourages Dubious Dismissals”

(.05 level). Respondents whose agency experiences were shaped by the potential for misuse in personnel functions tend to view at-will employment as discouraging good government and encouraging arbitrary dismissal. While the coefficients are in the right direction for “Unwarranted RIFs, the predictor fails to achieve statistical significance in all three regressions. The “Trust in Management” coefficients achieve statistical significance (.05 level) and are all in the right direction for all three regressions. It would appear that respondents who trust their supervisors to do the right thing in personnel actions tend to view at-will employment as an important management tool in government.

Discussion

When Georgia abolished state employee protections and abandoned its central personnel agency in favor of decentralization in 1996, one of the current authors viewed

- 17 -

the reform with skepticism. The history of civil service reform in the United States is well known: President Andrew Jackson, the outright conversion of votes to jobs characteristic of spoils politics, the Progressive reform movement, the Pendleton Act, and the struggle for equal rights and protection for public employees (Van Riper, 1958;

Shultz & Maranto, 1998; Condrey & Maranto, 2001). However, the results of this survey, coupled with one of the authors’ extensive consulting experience with state of

Georgia agencies over a period of twenty years, show that while not wholly positive, there has been no wholesale rush to spoils politics and corrupt government in Georgia.

This is in spite of three different gubernatorial administrations and a change in political party dominance since the original reform legislation was passed.

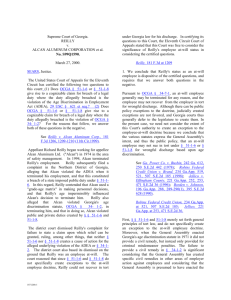

T ABLE 4: Peach State Poll Percent of State Population Agreeing With Statements About At-

Will Employment for State Workers

35%

30%

31%

25% 26% 26%

28%

20%

15%

21%

32%

25%

27%

10%

5%

0%

Leads to Greater

Accountability &

Responsiveness

Leads to Greater

Customer

Satisfaction

Provides Essential

Managerial

Flexibility

Makes State Jobs

Less Attractive to

Potential

Employees

Completely Agree

Somewhat Agree

Indeed, the Georgia public supports the notion of at-will employment for public employees (see Table 4). While minor incidents of state government corruption appear

- 18 -

occasionally in the state newspapers, Georgia government continues to operate in a fairly efficient and effective manner. This is contrary to what many scholars predicted.

Why? While we do not know with certainty why efficient and effective government continues in Georgia in the absence of employee protections, we begin to speculate as to potential, yet tentative, explanations:

Broad public support for at-will employment and symbolism

The relationship of public employment to elective politics

Complex bureaucracies and a developed economy

The changing nature of the workforce and the notion of psychological work contracts

The ongoing diminution in the differences between public and private sector employment

Public Support for At-Will Employment and Symbolism

As Table 4 illustrates, the general Georgia population supports at-will employment. Much of this support is symbolic: the public wants its elected leadership to reign in public excess. At-will employment is a way for elected officials to demonstrate to the public that they are ‘in charge’ and have control over the ship of state. While there is no evidence that at-will employment is improving state operations, it enjoys broad public support.

Public Employment and Elective Politics

No longer are jobs traded on a large-scale basis for votes as they once were. The era of Andrew Jackson has passed, yet many of the critics of at-will employment insist that patronage will return to the public sector once employee protections are abolished.

- 19 -

While there is anecdotal evidence of this in the State of Florida, there is little support for any widespread utilization of patronage politics in states adopting at-will employment systems. In fact, many Georgia HR professionals expressed their support for at-will employment in their written survey responses. One respondent asserted:

I believe that at-will employment has significantly improved the efficiency and effectiveness of our agency’s HR processes. I do not believe the abuses

(cronyism, firing competent employees, etc.) are any more common than they were previously.

Why is this so? The authors believe the answer is simple: the nature and relationship of public employment and elective politics has changed. Jobs no longer translate to votes, except for select elites. Interest group politics, lucrative government contracts, and privatization of government functions are now the fuel that power elections and electoral politics. Who gets what from government is no longer determined by the simple formula of votes for jobs, but rather it is a complex calculus involving contracts and large private interests. Hence the move toward the ‘hollow state’ with extensive privatization of governmental functions, outsourcing, and the like.

Complex Bureaucracies and a Developed Economy

At-will employment has not resulted in widespread corruption in state governments in the United States. Most state bureaucracies employ tens of thousands of employees, the sheer complexity of which negates coordinated efforts to politicize entire bureaucracies. While patronage perhaps occurs at the margins, it does not appear to have adversely influenced governmental operations. The fact that respondents’ political views did not influence their assessment of at-will employment provides insight to this conclusion. It may be that at-will employment is not strictly a political or partisan issue as some have contended.

- 20 -

However, in smaller bureaucracies with less developed economies, protection for public employees may well prove valuable. The authors believe that elected and bureaucratic reaction to at-will employment is in fact situational and dependent on the complexity of bureaucratic activity as well as the maturity and health of the economy in which it is implemented.

Changing Nature of the Workforce

The authors also speculate that there may be generational trends at play that account for support for at-will employment. As noted, the data analysis demonstrates the antipathy of those respondents with longer tenure in office to at-will employment in government. In contrast, younger workers in the United States no longer expect to form long-term psychological contracts with their employers (Riccucci, 2006; West, 2005;

Tulgan, 1997). At-will employment may suit the next generation of workers, who enter the workforce anticipating that their career path will involve a number of different jobs with different organizations.

Respondents expressed similar sentiments in comments recorded on their surveys.

One such respondent stated:

I think that at will employment is a non-issue for new and younger employees, but a concern for long term employees.

Another respondent observed:

Only classified employees express concern regarding at-will employment. New employees appear unconcerned.

These comments highlight the contrast between younger and older workers’ views of job protections. At-will employment does not pose as much of a threat to younger workers’ notions of career as it does to previous generations, who depended on and prided

- 21 -

themselves in the security of a long tenure and accompanying job protections with a particular organization.

There is more to explore with regard to differences in generational attitudes towards at-will employment, especially with the growing importance of succession planning as baby boomer civil servants begin to retire from the public sector workforce.

The outcomes of this generational transition in the workforce are tied to the future and success of at-will employment as an alternative to traditional human resource management.

Blurring of Public and Private Sector Employment

Over the past several decades, there has been a continuing diminution of the differences between public and private sector employment. In previous generations, employees sought public sector positions that offered career employment and civil service protections. As these protections become scarce, public and private employment differences begin to blur. It remains to be seen if this phenomenon will lead to more competitive wages for public sector employment; the alternative is that public agencies, sans civil service protections and competitive wages, could become an employer of last resort.

Conclusion

Civil service reforms intended to improve efficiency by strengthening managerial authority have been a recurrent theme in the field of public administration since its inception . Indeed, the 1937 Brownlow Commission sought a more managementoriented system of public personnel administration (Van Riper, 1958). Frederick Mosher,

- 22 -

in Democracy in the Public Service , argues that human resource management systems

“should be decentralized and delegated to bring into more immediate relationship with the middle and lower managers they served” (1982, p. 86). By decentralizing the human resource function and delegating it to each individual state agency, the Georgia reform has enacted Mosher’s vision.

The reforms in Georgia and other states represent a clear reaction to overlycentralized, overly-bureaucratized human resource systems. A shift to more decentralized, at-will based arrangements for the delivery of human resource management services appears to be on the rise. While the authors are not apologists for at-will employment, its persistence and expansion warrants explanations, albeit tentative ones.

It is incumbent upon the field to recognize that at-will employment is more than a fleeting phenomenon, to seek explanations for its persistence and expansion, and to guide its implementation. The alternative is a diminished role for the field of public human resource management. Further research and dialogue is needed to continue to build upon this data and to shed further light into this yet not fully explored area of public human resource management.

- 23 -

References

Battaglio, R. P., & Condrey, S. E. (2006). Civil Service Reform: Examining State and

Local Cases. Review of Public Personnel Administration , 26(2), 118-138.

Bowman, J. S., & West, J. P. (2006). Ending Civil Service Protections in Florida

Government: Experiences in State Agencies. Review of Public Personnel Administration ,

26(2), 139-157.

Coggburn, J. (2005). The Benefits of Human Resource Centralization: Insights From a

Survey of Human Resource Directors in Decentralized State. Public Administration

Review, 65(4), 424-435.

Coggburn, J. (2006). At-Will Employment in Government: Insights From the State of

Texas. Review of Public Personnel Administration , 26(2), 158-177.

Condrey, S. E. (2002). Reinventing State Civil Service Systems. Review of Public

Personnel Administration , 22(2), 114-124.

Condrey, S. E., & Maranto, R. (2001). Radical Reform of the Civil Service . Lanham,

MD: Lexington Books.

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale Development: Theory and Applications , 2 nd edition.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dillman, D. A. (1978). Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method . New

York: John Wiley.

Gossett, C. W. (2002). Civil Service Reform: The Case of Georgia. Review of Public

Personnel Administration , 22(2), 94-113.

Hays, S. W., & Sowa, J. E. (2006). A Broader Look at the “Accountability” Movement:

Some Grim Realities in State Civil Service Systems. Review of Public Personnel

Administration , 26(2), 102-117.

Kellough, J. E. & Nigro, L. N., (Eds.). (2006). Civil Service Reform in the States:

Personnel Policies and Politics at the Sub-National Level . New York: State University of

New York Press.

Kettl, D. F. (2000). The Global Management Revolution: A Report on the

Transformation of Governance . Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Mosher, F. C. (1982). Democracy and the Public Service (2 nd Ed.). New York: Oxford

University Press.

- 24 -

Office of Program Policy Analysis & Government Accountability (OPPAGA), Florida

Legislature. (April 2006). While Improving, People First Still Lacks Intended

Functionality, Limitations Increase State Agency Workload and Costs. Report No. 06-39.

Riccucci, N. M. (2006). Managing Diversity: Redux. In N. M Riccucci (Ed.), Public

Personnel Management: Current Concerns, Future Challenges 4 rd Edition (pp. ). New

York: Longman Publishers.

Savas, E. S. (2000). Privatization and Public Private Partnerships . New York:

Chatham House.

Shultz, D. A., & Maranto, R. (1998). The Politics of Civil Service Reform . New York:

Peter Lang.

State of Georgia, Georgia Merit System, personal correspondence, March 30, 2006.

Thompson, F. J. (1975). Personnel Policy in the City: The Politics of Jobs in Oakland .

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tulgan, B. (1997). The Manager’s Pocket Guide to Generation X . Amherst, MA: HRD

Press.

Van Riper, P. P. (1958). History of the United States Civil Service . Evanston, IL: Row,

Peterson and Company.

West, J. P. (2005). Managing an Aging Workforce: Trends, Issues, and Strategies. In S.

E. Condrey (Ed.), Handbook of Human Resources Management in Government 2 nd

Edition (pp.164-188). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- 25 -

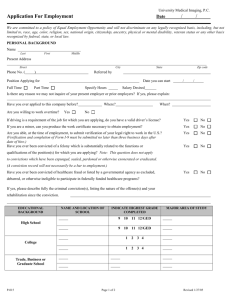

Appendix A - At-Will Employment in Georgia: A Survey of State HR Professionals

PART I: At-Will In General

Please circle the number corresponding to your level of agreement or disagreement with each of the following statements related to at-will employment in government in general.

Please be assured that your responses are completely anonymous.

In GENERAL, at-will employment in government. . .

1.

Leads to greater customer satisfaction for citizens.

2.

Leads to greater government accountability and responsiveness to the public.

Strongly

Disagree

1

1

Disagree

2

2

Neither

Agree/

Disagree

3

3

Agree

4

4

Strongly

Agree

5

5

1 2 3 4 5 3.

Has streamlined the hiring/firing process.

4.

Helps ensure employees are responsive to the goals and priorities of agency administrators.

5.

Provides needed motivation for employee performance.

6.

Makes the HR function more efficient.

7.

Provides essential managerial flexibility over the HR function.

8.

Represents an essential piece of modern government management.

9.

Makes employees feel more secure about their jobs.

10.

Discourages employees from taking risks that could lead to program or policy innovation.

11.

Discourages employees from reporting agency wrongdoing (or “blowing the whistle”).

12.

Discourages employees from freely voicing objections to management directives.

13.

Could—by not requiring a rationale or justification for terminating employees— negatively affect managers’ decision-making in other non-HR decisions.

14.

Could—by not requiring a rationale or justification for terminating employees— make public employees less sensitive to issues of procedural fairness.

15.

Is at odds with the public sector’s traditional emphasis on merit in human resources decisions.

16.

Makes state government jobs less attractive to current and future employees than would be the case if there was more job security.

17.

Gives an upper-hand to employers relative to employees in the employment relationship.

18.

Is sometimes used to fire competent employees so other people with friends or connections to government can be hired.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

- 26 -

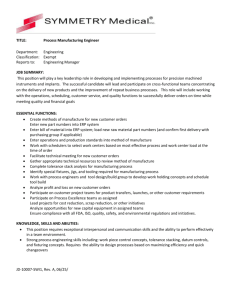

PART II: At-Will In Your Agency

Please circle the number corresponding to your level of agreement or disagreement with each of the following statements related to at-will employment in your agency.

Please be assured that your responses are completely anonymous.

In MY agency . . . Strongly

Disagree

1

Disagree

2

Neither

Agree/

Disagree

3

Agree

4

Strongly

Agree

5 1.

Employees are more productive because they are employed at-will.

2.

The lack of job security is made up for with competitive compensation (salary and benefits).

3.

The lack of job security makes recruiting and retaining employees difficult.

4.

Even though employment is at-will, most employee terminations are for good cause.

5.

Even if an employee is terminated at-will, we maintain documentation to justify the termination should a lawsuit arise.

6.

Concern about wrongful termination and discrimination lawsuits limits our use of at-will termination.

7.

Managers treat employees fairly and consistently when it comes to HR decisions.

8.

Employees trust management when it comes to HR decisions.

9.

I know of a case where a competent employee was fired at-will so that another person with friends or connections to government could be hired.

10.

Employees have been terminated at-will because of personality conflicts with management.

11.

Employees have been terminated at-will because of poor performance.

12.

Employees have been terminated at-will because of changing managerial priorities/objectives.

13.

Employees have been terminated at-will in order to meet agency budget shortfalls.

14.

Employees have been terminated at-will in order to meet agency downsizing goals.

15.

Employees have been terminated at-will in order to meet mandated managementto-staff ratios.

16.

Employees have been terminated at-will for politically motivated reasons.

17.

At-will employment has led to pay discrepancies among employees with similar duties.

18.

Employees feel that they can trust the organization to treat them fairly.

19.

We include disclaimers in our policies and procedures manuals and employee handbooks stating that they do not alter the at-will employment relationship.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

- 27 -

PART II (Continued): At-Will in Your Agency

In MY agency. . .

20.

We clearly state in our job announcements and applications that employment with the agency is at-will.

21.

We require employees to sign a form acknowledging that they are employed at-will by the agency.

22.

We provide training to managers who make HR decisions on the legal exceptions to at-will employment and on how to preserve the at-will employment status.

23.

We have improved our employee selection processes to better ensure employees hired fit the job and agency culture.

24.

We give employees clear expectations about what is desirable and undesirable performance (e.g., through orientation and annual performance reviews).

Strongly

Disagree

1

1

1

1

1

Disagree

2

Neither

Agree/

Disagree

3

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

Agree

4

4

4

4

4

Strongly

Agree

5

5

5

5

5

25.

We provide training to supervisors on how to effectively identify and handle problem employees (to reduce at-will terminations).

26.

We have adopted or considered adopting a termination for good cause policy in order to reduce our total litigation risks (e.g., for wrongful termination, discrimination, etc.).

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

PART III: At-Will In Other Agencies

Please circle the number corresponding to your level of agreement or disagreement with each of the following statements related to your knowledge of at-will employment in other state agencies. Please be assured that your responses are completely anonymous.

In ANOTHER agency. . . Strongly

Disagree

1

Disagree

Neither

Agree/

Disagree Agree

1.

I know of a case where a competent employee was fired at-will so that another person with friends or connections to government could be hired.

2.

Employees have been terminated at-will for politically motivated reasons. 1

2

2

3

3

4

4

3.

At-will employment has led to pay discrepancies among employees with similar duties.

1 2

PART IV: Respondent Information

For items #1-2 , please provide the written information requested..

For items #3-11, please circle the letter corresponding to the appropriate response for each question about you and your agency.

Please be assured that your responses are completely anonymous.

3 4

1.

What percentage of your agency’s employees serve at-will? (Please write the % in the space provided.) _________ %

2.

Approximately how many full-time equivalent (FTE) employees are authorized for your agency? _________ FTE employees

3.

What is your age range? (Circle one.)

A. 24 or less

B. 25-34

C. 35-44

D. 45-54

E. 55-64

F. 65 or over

Strongly

Agree

5

5

5

- 28 -

4.

What is your gender? (Circle one.)

A. Female

5.

What is your race/ethnicity? (Circle all that apply.)

B. Male

A. American Indian or Alaska Native

B. Asian

C. Black or African American

D. Hispanic or Latino

D. Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

E. White

F. Some Other race

6.

In general, which of the following best describes your political views? (Circle one.)

A. Very Conservative

B. Conservative

C. Moderate

D. Liberal

E. Very Liberal

7.

Have you worked in the private sector in an HR position similar to the one you hold now? (Circle one.)

A. Yes B. No

8.

How many years have you worked in the public sector? (Circle one.)

A. Less than 5 years

B. 5 to 10 years

C. 11 to 15 years

D. 16 to 20 years

E. 21 to 25 years

F. 26 years or more

9.

How many years have you worked in the field of HR? (Circle one.)

A. Less than 5 years

B. 5 to 10 years

C. 11 to 15 years

D. 16 to 20 years

E. 21 to 25 years

F. 26 years or more

10.

What is your highest level of academic attainment? (Circle one.)

A. High school diploma

B. 2 year college degree

C. 4 year college degree

D. Master’s degree

E. Law degree

F. Ph.D. or equivalent

11.

Which of the following professional designations do you hold (Circle all that apply.)

Please provide any additional comments regarding at-will employment:

A. IPMA-HR-CS (Certified Specialist) C. SHRM – PHR (Professional in Human Resources)

B. IPMA-HR-CP (Certified Professional) E. SHRM-SPHR (Senior Professional in Human Resources)

Thank you for completing the At-Will Employment in Georgia Survey. Your opinions are important!

Please fold your completed survey and return it in the postage-paid envelope provided.

Remember to separately mail your survey respondent postcard and indicate if you want to receive summary results of the survey.

- 29 -