Case No. 02SC911 - Colorado State Judicial Branch

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Opinions of the Colorado Supreme Court for the past twelve months are available to the public and can be accessed through the

Court’s homepage at http://www.courts.state.co.us/supct/supctca seannctsindex.htm

and are posted on the

Colorado Bar Association homepage at www.cobar.org

.

ADVANCE SHEET HEADNOTE

May, 24 2004

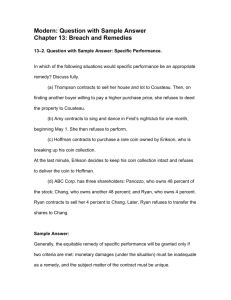

No. 02SC911, Szaloczi v. John R. Behrmann Revocable Trust-

Colorado Dissenters’ Rights Act-Exclusivity Provision-

Exception to the Exclusivity Provision-Payment of Fair

Value as Shareholder’s Remedy-Equitable Remedy

A former shareholder of a closely held corporation,

19 John R. Behrmann Revocable Trust (“the Behrmann Trust”),

20 brought this compensatory damages action in the district

21 court for breach of fiduciary duty and “conspiracy” against

22 the officers and directors of the corporation that sold its

23 assets to another corporation (“compensatory damages

24 action”).

25 Having brought this compensatory damages suit, the

26 Behrmann Trust then elected, under § 7-113-102(1), 2 C.R.S.

27 (2003), to dissent from the sale and obtain fair value for

28 its shares under the prescribed statutory procedures. When

29 the Behrmann Trust contested the amount of payment the

30 corporation had tendered, the corporation initiated a

31 judicial appraisal suit under § 7-113-301, 2 C.R.S. (2003).

1 The trial court dismissed the Behrmann Trust’s action

2 for compensatory damages now before the supreme court,

3 ruling that its sole remedy under these circumstances is

4 the statutory appraisal remedy. The court of appeals

5 reversed and reinstated the action.

6 The supreme court agrees with the trial court and

7 disagrees with the court of appeals. The supreme court

8 holds that, because the Behrmann Trust failed to bring an

9 action for equitable relief on the basis of illegality or

10 fraud, it has not invoked the exception to the exclusivity

11 provision of the appraisal remedy. Because the Behrmann

12 Trust is bound by the exclusivity provision, the trial

13 court did not err in dismissing this action for

14 compensatory damages. Accordingly, the supreme court

15 reverses the judgment of the court of appeals.

16

2

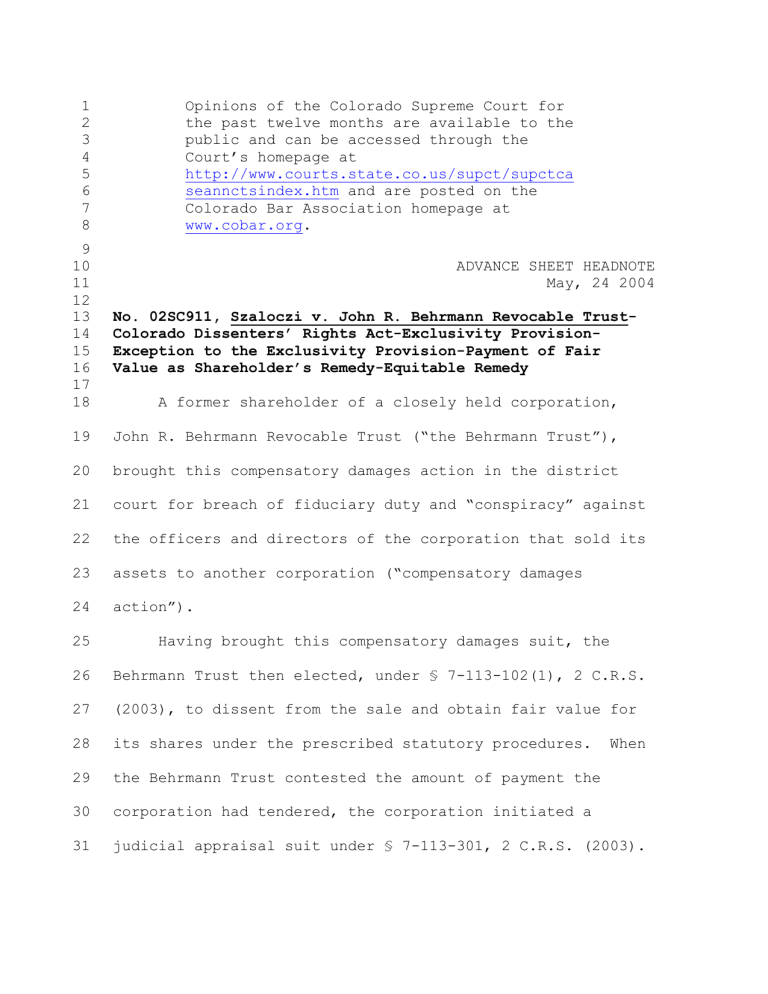

SUPREME COURT, STATE OF COLORADO

Two East 14 th Avenue

Denver, Colorado 80203

Certiorari to the Colorado Court of Appeals

Court of Appeals Case No. 01CA0775

Case No. 02SC911

11

12

13

14

15

8

9

10

5

6

7

1

Petitioners:

ERIC L. SZALOCZI, MICHAEL P. BATZER, JAY CRIST, ROBERT S. PFEIFFER,

ALLAN WISE, MICHAEL CASKEY, ROLAND DeBRUYN, JEFFREY WEBER, and

BRUCE WILLIAMS, v.

Respondent :

JOHN R. BEHRMANN REVOCABLE TRUST.

JUDGMENT REVERSED

EN BANC

MAY 24, 2004

2 Holme Roberts & Owen, LLP

3

4

David S. Steefel

Michael J. Hofmann

Denver, Colorado

Attorneys for Petitioner

Benjamin, Bain & Howard, LLC

James W. Bain

Wesley B. Howard

Greenwood Village, Colorado

Attorneys for Respondent

JUSTICE HOBBS delivered the Opinion of the Court.

1 We granted certiorari in this case to review the court

2 of appeals decision in John R. Behrmann Revocable Trust v.

3 Szaloczi, 74 P.3d 371 (Colo. App. 2002).

1 A former

4 shareholder of a closely held corporation, John R. Behrmann

5 Revocable Trust (“the Behrmann Trust”), brought this

6 compensatory damages action in the district court for

7 breach of fiduciary duty and “conspiracy” against the

8 officers and directors of the corporation that sold its

9 assets to another corporation (“compensatory damages

10 action”).

11 The complaint alleges that the “Defendants arranged to

12 take substantially more than [the Behrmann Trust], a

13 minority shareholder in a closed corporation, from the sale

14 of substantially all the corporate assets, by paying

15 themselves as officers rather than as shareholders.” The

16 prayer for relief is only for compensatory damages.

2 Having

17 brought this compensatory damages suit, the Behrmann Trust

1 The certiorari issue is “Whether the court of appeals erred by holding that a shareholder who dissented from a corporate action and sought the fair value of its shares in a statutory appraisal suit also may maintain legal claims for money damages allegedly arising from the dissented-from transaction.”

2

Award of compensatory damages is a legal remedy.

Kirk v. Denver Publ’g. Co., 818 P.2d 262, 265 (Colo.

1991). Equitable remedies include actions such as rescission, injunctions, and reformation. Dan B.

Dobbs, Law of Remedies §§ 2.1(6), 3.1 (2d ed. 1993).

2

1 elected, under § 7-113-102(1), 2 C.R.S. (2003), to dissent

2 from the sale and obtain fair value for its shares under

3 the prescribed statutory procedures. When the Behrmann

4 Trust contested the amount of payment the corporation had

5 tendered, the corporation initiated a judicial appraisal

6 suit under § 7-113-301, 2 C.R.S. (2003). In that separate

7 action, now pending review in the court of appeals, another

8 division of the district court--utilizing the services of a

9 special master--set the compensation owed to the Behrmann

10 Trust for its shares (“appraisal action”).

11 The trial court dismissed the Behrmann Trust’s action

12 for compensatory damages now before us, ruling that its

13 sole remedy under these circumstances is the statutory

18

19

20

21

14 appraisal remedy. The court of appeals reversed and

15 reinstated the action. In doing so, the court of appeals

16 relied on the exception to the statute’s exclusivity

17 provision contained in § 7-113-102(4), 2 C.R.S. (2003).

22

23

3

1 The statute provides that the shareholder may challenge the

2 “corporate action” if that action is “unlawful or

3 fraudulent with respect to the shareholder or the

4 corporation.” 3

5 We agree with the trial court and disagree with the

6 court of appeals. We hold that, because the Behrmann Trust

7 failed to bring an action for equitable relief on the basis

8 of illegality or fraud, it has not invoked the exception to

9 the exclusivity provision of the statute’s appraisal

10 remedy. Because the Behrmann Trust is bound by the

11 exclusivity provision, the trial court did not err in

12 dismissing this action for compensatory damages.

13 Accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the court of

14 appeals.

15

16

I.

Preston Reynolds & Company, Inc. (“PRC”), was a

17 closely held Colorado corporation engaging in the oil and

18 gas exploration and leasing business. The Behrmann Trust

3

Section 7-113-102(4), also known as the “exclusivity provision,” states:

A shareholder entitled to dissent and obtain payment for the shareholder’s shares under this article may not challenge the corporate action creating such entitlement unless the action is unlawful or fraudulent with respect to the shareholder or the corporation.

§ 7-113-102(4).

4

1 was a minority shareholder of PRC. John Behrmann, the sole

2 trustee of the Behrmann Trust, also served as Chairman of

3 the PRC Board of Directors. On November 1, 1999, the other

4 shareholders of PRC voted to remove Behrmann as Chairman.

5 However, the Behrmann Trust remained a PRC shareholder.

6 As required by the Colorado Dissenters’ Rights Act

7 (“the Act”), PRC provided notice to the shareholders of a

8 meeting on April 17, 2000 to vote on the sale of

9 substantially all of PRC’s assets to WBI Production, Inc.

10 (“WBI”).

4 In accordance with the Act, the Behrmann Trust

11 delivered written notice to PRC indicating its intent to

12 demand payment for its shares if the WBI sale was

13 effectuated. At the April 17th meeting, the Behrmann Trust

14 voted all of its shares against the sale as required under

15 the Act. However, the majority of shareholders approved

16 the sale.

17 On April 26, 2000, PRC sent out its dissenters’ notice

18 which informed the Behrmann Trust that it was entitled to

19 dissent and must deliver its demand for payment together

20 with the share certificates to PRC.

4

Under section 7-113-102, a sale of substantially all of the corporation’s assets invokes a shareholder’s right to dissent. § 7-113-102(c), 2 C.R.S. (2003).

5

1 On May 24, 2000, before the Behrmann Trust delivered

2 its demand for payment, it filed this compensatory damages

3 action against the officers and directors of PRC for breach

4 of fiduciary duty and conspiracy to deprive it of the value

5 of its shares. The complaint requested compensatory

6 damages and did not seek equitable relief. The nature of

7 the complaint is that the other shareholders structured the

8 asset sale for their personal benefit. The Behrmann Trust

9 alleged that the other shareholders, acting in their

10 capacity as officers and directors: (1) withheld

11 information; (2) granted themselves stock options below

12 market value; (3) extended stock options beyond the

13 expiration dates; (4) negotiated personal employment

14 contracts for themselves in connection with the sale; and

15 (5) arranged to take more from the sale of assets by paying

16 themselves as officers rather than as shareholders.

17 According to the complaint, these events leading up to the

18 sale of the corporate assets, which the Behrmann Trust

19 voted against, affected the value of the Behrmann Trust’s

20 interest in the corporation.

21 On May 26, 2000, two days after the Behrmann Trust

22 filed its compensatory damages action, it demanded payment

23 for its shares in PRC and delivered the trust stock

24 certificates, pursuant to the Act.

6

1 On July 7, 2000, PRC paid the Behrmann Trust, in the

2 amount of $6,145,191.31, pursuant to section 7-113-206, 2

3 C.R.S. (2003). This amount represented PRC’s estimate of

4 fair value and accrued interest. The Behrmann Trust

5 accepted this payment, but demanded additional payment from

6 PRC claiming that PRC paid less than fair value for the

7 shares.

8 In turn, PRC commenced the statutory appraisal action

9 in another division of the district court to determine the

10 fair value of the shares and accrued interest, pursuant to

11 section 7-113-301, 2 C.R.S. (2003). Utilizing the services

12 of a special master, the district court entered its

13 decision regarding the fair value of the Behrmann Trust

14 shares. The special master found that the Behrmann Trust

15 was entitled to an additional $681,174 for the fair value

16 of its shares. The district court adopted the special

17 master’s findings and conclusions of law. The Behrmann

18 Trust is currently challenging the adequacy of that award

19 by appeal to the court of appeals.

20 The trial court dismissed the compensatory damages

21 action now before us. In doing so, it ruled that the

22 appraisal remedy under sections 7-113-101 to -301 of the

23 Act is the Behrmann Trust’s sole remedy under the

24 circumstances. Relying on Delaware Law, the court of

7

1 appeals reversed. It agreed that the Behrmann Trust could

2 not “pursue a separate action for certain types of

3 mismanagement.” But, it characterized the complaint as

4 alleging a claim for “constructive fraud regarding actions

5 unrelated to the WBI sale.” John R. Behrmann Revocable

6 Trust, 74 P.3d at 375. The court of appeals did not

7 address whether the complaint requested equitable relief or

8 the effects of requesting compensatory damages; it simply

9 construed the breach of fiduciary duty allegations as an

10 implied allegation of “constructive” fraud and concluded

11 that the cause of action fell within the exception for

12 fraud, which the trial court should not have dismissed.

13 The issue in this case is whether, under the Colorado

14 Dissenters’ Rights Act, a shareholder who dissents from a

15 sale of corporate assets and seeks payment for the fair

16 value of its shares may also pursue a separate claim for

17 compensatory damages against the officers and directors who

18 acted for the corporation in approving the sale.

19 II.

20 We agree with the trial court and disagree with the

21 court of appeals. We hold that, because the Behrmann Trust

22 failed to bring an action for equitable relief on the basis

23 of illegality or fraud, it has not invoked the exception to

24 the exclusivity provision of the statute’s appraisal

8

1 remedy. Because the dissenting shareholder is bound by the

2 exclusivity provision, the trial court did not err in

3 dismissing this action for compensatory damages.

4 Accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the court of

5 appeals.

6

7

A. Standard of Review

The issue before us requires construction of the Act’s

8 exclusivity provision. This is a question of law we review

9 de novo. Leonard v. McMorris, 63 P.3d 323, 326 (Colo.

10 2003). We must construe the statute to effectuate the

11 General Assembly’s intent; in doing so, we examine the

12 statute as a whole, harmonizing where possible all of its

13 parts. Id.

14 In interpreting our statute, we draw upon fundamental

15 principles of statutory construction. When our statute is

16 patterned upon the law of other jurisdictions or model

17 codes, we may draw upon applicable precedent in conducting

18 our analysis. Pueblo Bancorporation v. Lindoe, Inc., 63

19 P.3d 353, 368 (Colo. 2003). “Because the legislature has

20 consistently relied on the [Model Business Corporation Act]

21 when fashioning the corporate laws of this state we find

22 the views of the MBCA on this issue to be persuasive.” Id.

23 We assume that the General Assembly was aware of the prior

24 decisional law of other jurisdictions that the drafters of

9

1 the MBCA relied on when enacting the MBCA. See Semendinger

2 v. Brittain, 770 P.2d 1270, 1272 (Colo. 1989) (“The General

3 Assembly is presumed to be cognizant of prior decisional

4 law when enacting or amending statutes.”). Moreover, we

5 presume that the General Assembly’s intent is the same as

6 the intent of the MBCA drafters. Pueblo Bancorporation, 63

7 P.3d at 368 (citing Copper Mountain Inc. v. Poma of

8 America, Inc., 890 P.2d 100 (Colo. 1995)). Thus, we now

9 examine the relevant case law that the MBCA drafters relied

10 upon when drafting the exclusivity provision.

11

12

B. Colorado Dissenters’ Rights Act

The Colorado Dissenters’ Rights Act sets forth a

13 special statutory procedure by which a shareholder may

14 dissent from certain corporate actions and obtain payment

15 of fair value for its shares; such corporate actions

16 include a sale of the corporation’s assets. § 7-113-

17 102(1)(c) & (d). We refer to this procedure as the

18 statutory appraisal remedy.

19 1.

Procedures

20 This special statutory design sets out a series of

21 deadlines and procedures to ensure that the corporation can

22 timely pursue new opportunities while minority shareholders

23 are promptly compensated for the fair value of their

24 shares.

10

1 If a proposed corporate action giving rise to

2 dissenters’ rights is submitted to a vote at a shareholder

3 meeting, the corporation must give notice to all

4 shareholders. § 7-113-201(1). The notice must include a

5 statement that all shareholders are entitled to dissent.

6 Id. Before the vote is taken, shareholders who dissent

7 must give written notice of their intent to demand payment

8 in the event the proposed corporate action is effectuated.

9 § 7-113-202(1)(a).

10 If the corporate action is subsequently authorized,

11 the corporation--no later than ten days after the effective

12 date of the corporate action--must give written notice to

13 all shareholders who are entitled to demand payment. § 7-

14 113-203(1). The notice must include, among other matters,

15 a date by which the corporation must receive the payment

16 demand. § 7-113-203(2)(e). This date cannot be less than

17 thirty days after this notice is given. Id.

18 Upon receiving such notice, the dissenting shareholder

19 must demand payment. § 7-113-204(1)(a). After the

20 effective date of the corporate action, the shareholder has

21 only the right to receive fair value for the shares. § 7-

22 113-204(2). “Fair value” means the value of the

23 dissenter’s shares “immediately before the effective date

24 of the corporate action to which the dissenter objects,

11

1 excluding any appreciation or depreciation in anticipation

2 of the corporate action except to the extent that exclusion

3 would be inequitable.” § 7-113-101(4). The demand for

4 payment is irrevocable unless: (1) the effective date of

5 the corporate action does not occur within sixty days after

6 the date set by the corporation; or (2) the corporation

7 fails to make payment within sixty days after the date set

8 by the corporation for receiving the payment demand. § 7-

9 113-204(3).

10 Upon the effective date of the corporate action, or

11 upon receipt of the payment demand, whichever is later, the

12 corporation must pay each dissenting shareholder the amount

13 that the corporation estimates to be the fair value of the

14 shareholder’s shares. § 7-113-206(1). If a dissenting

15 shareholder is dissatisfied with the payment, it must give

16 written notice of its estimate of fair value. § 7-113-

17 209(1).

18 Within sixty days after receiving the dissenting

19 shareholder’s estimate of fair value, the corporation may

20 commence an action in court to determine the fair value of

21 the shares. § 7-113-301(1). If the corporation does not

22 commence the proceeding within this time period, it must

23 pay each dissenting shareholder the amount demanded. Id.

24 The jurisdiction of the court is plenary and exclusive. §

12

1 7-113-301(4).

5 The dissenting shareholder is entitled to

2 fair value for its shares as determined by the court. § 7-

3 113-301(5).

4 2. Exclusivity Provision

5 Once the shareholder elects to dissent and demand

6 payment, the Act prohibits a challenge to the corporate

7 action except for a narrow exception for unlawful or

8 fraudulent conduct. Section 7-113-102(4), also known as

9 the “exclusivity provision,” states:

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

A shareholder entitled to dissent and obtain payment for the shareholder’s shares under this article may not challenge the corporate action creating such entitlement unless the action is unlawful or fraudulent with respect to the shareholder or the corporation.

§ 7-113-102(4) (emphasis added).

18 Whether the exception permits a dissenting shareholder

19 to bring an action for compensatory damages in addition to

20 invoking the statutory appraisal remedy is a matter of

21 first impression in this court. Thus, we now turn to the

22 Act and case law to construe this provision.

23 In 1993, the General Assembly repealed the entire

24 Colorado Corporate Code and enacted the Revised Model

25 Business Corporation Act of 1984 (“MBCA”). Pueblo

5

The court can hear both the appraisal action and an action for equitable relief, if brought.

13

1 Bancorporation, 63 P.3d at 368. In doing so, the General

2 Assembly adopted the MBCA’s exclusivity provision. Compare

3 § 7-113-102(4), with Model Bus. Corp. Act § 13.02(b)(1984).

4 The official comment to the MBCA explains that the Act

5 “basically adopts the New York formula as to exclusivity of

6 the dissenters’ remedy . . . .” Model Bus. Corp. Act §

7 13.02 cmt. at 1366 (1984).

8 The MBCA drafters designed the exclusivity section to

9 “recognize and preserve the principles that have developed

10 in the case law of Delaware, New York and other states with

11 regard to the effect of dissenters’ rights on other

12 remedies of dissident shareholders.” Id. at 1367. The

13 official comment summarizes the principles that developed

14 from this case law:

21

22

23

24

25

26

15

16

17

18

19

20

The [appraisal] remedy is the exclusive remedy unless the transaction is “unlawful” or

“fraudulent” . . . . If the corporation attempts an action in violation of the corporation law on voting, in violation of clauses in articles of incorporation prohibiting it, by deception of shareholders, or in violation of fiduciary duty .

. . the court’s freedom to intervene should be unaffected by the presence or absence of dissenters’ rights under this chapter.

Id. at 1366.

27 The “New York formula” provides that appraisal is the

28 exclusive remedy, except that an individual may bring a

29 proceeding in equity when corporate action is alleged to be

14

1 fraudulent or illegal. Breed v. Barton, 429 N.E.2d 128,

2 129-31 (N.Y. 1981); Theodore Trust U/A Dated December v.

3 Smadbeck, 717 N.Y.S.2d 7, 8 (2000).

6 The dissenting

4 shareholder must seek some form of equitable relief; it is

5 not sufficient to plead a cause of action over which equity

6 has jurisdiction. Walter J. Schloss Assocs. v. Arkwin

7 Industries, Inc., 460 N.E.2d 1090, 1090, (N.Y. 1984)

8 (adopting dissent of Walter J. Schloss Assocs. v. Arkwin

9 Industries Inc., 455 N.Y.S.2d 844, 847, 850 (1982)(Mangano,

10 J., dissenting)).

11 Moreover, dissenting shareholders cannot obtain relief

12 in the form of compensatory damages. Breed, 429 N.E.2d at

13 130. Rather, “any monetary recovery, if available at all,

14 can only be ancillary to a grant of some form of equitable

15 relief” from the corporate action. Id. at 131; Burke v.

16 Jacoby, 981 F.2d 1372, 1380 (2d Cir. 1992) (interpreting

17 New York Law and dismissing the dissenting shareholder’s

18 complaint because it made no attempt to obtain traditional

19 equitable relief but only requested compensatory and

6

New York’s exclusivity provision is the same today as it was when the MBCA was drafted. N.Y. Business Corporation

Law § 623(k)(McKinney 1981); see N.Y. Business Corporation

Law § 623(k)(McKinney 2003). That provision states that a dissenting shareholder can “bring or maintain an appropriate action to obtain relief on the ground that such corporate action will be or is unlawful or fraudulent as to him.” Id.

15

1 punitive damages). The New York Court of Appeals explained

2 that the policy behind prohibiting an action for

3 compensatory damages, in addition to invoking the statutory

4 appraisal remedy, is to avoid duplicate damages. The

5 appraisal action is the forum for full monetary recovery of

6 the dissenting shareholder’s shares:

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Allowing the prosecution of a legal action for damages after the exercise of the right of appraisal would be unnecessarily duplicative in that full and proper monetary recovery of the fair value of the dissenters’ shares may be obtained in the appraisal proceeding.

Breed, 429 N.E.2d at 130.

15 New York and Delaware share the same basic principle

16 that the exclusivity exception to the statutory appraisal

17 remedy permits equitable relief and does not allow a

18 separate claim for compensatory damages. See Weinberger v.

19 UOP, Inc., 457 A.2d 701, 714 (Del. 1983); Ryan v. Tad’s

20 Enters., Inc., 709 A.2d 682, 698-99 (Del. Ch. 1996).

21 Delaware has a long history of equitable actions in

22 the corporate setting. Where fraud, misrepresentation,

23 self-dealing, deliberate waste of corporate assets, or

24 gross and palpable overreaching are involved, a dissenting

25 shareholder may bring an equitable action. Weinberger, 457

16

1 A.2d at 714.

7 In Delaware, a dissenting shareholder may

2 receive rescissory damages in an equitable action. Id. In

3 this situation, the court awards rescissory damages when a

4 traditional form of equitable relief, like rescission, is

5 not feasible.

8 Nagy v. Bistricer, 770 A.2d 43, 56 (Del. Ch.

6 2000) (“Only in an equitable action can [the plaintiff]

7 possibly obtain rescission or rescissory damages.”).

8 Nevertheless, where the dissenting shareholder seeks

9 an appraisal and equitable relief, the Delaware court

10 limits the dissenting shareholder to a single recovery

7

In Weinberger, the minority shareholder sought to rescind the merger, or in the alternative, rescissory damages. The court held that the long completed transaction was too involved to undo and held that the Chancellor had discretion to award relief in the form of monetary damages.

Although the question of whether the shareholder could recover both the appraisal remedy and legal damages was not before the court, the court’s opinion points to appraisal as being the primary financial remedy. Weinberger v. UOP,

Inc., 457 A.2d 701, 714 (Del. 1983).

8

Rescission is a traditional form of equitable relief that

“restores the parties to the status quo before sales of the shares were made . . . .” Lynch v. Vickers Energy Corp.,

429 A.2d 497, 501 (Del. 1981) (reversed on other grounds).

When a party recovers money damages in connection with rescission, those damages are more accurately called restitution:

The term rescission refers to the avoidance of the transaction or the calling off of the deal, and not to the particular form of restitution that may be granted once the transaction is avoided . . . . Very commonly the restitution granted when the term rescission is used is restitution in money.

Dobbs, supra, § 4.3(6).

17

1 judgment. Cede & Co. v. Technicolor, Inc., 542 A.2d 1182,

2 1191 (Del. 1988); see also William M. Fletcher, Cyclopedia

3 Corporations § 5906.30 (perm. ed., rev. vol. 2000).

4 Moreover, Delaware law, like New York law, prevents a

5 dissenting shareholder from maintaining an action for

6 compensatory damages in addition to the statutory appraisal

7 remedy.

8 The MBCA specifically states that it follows the New

9 York formula. The official comment referred to the court’s

10 equitable powers when it stated that “the court’s freedom

11 to intervene should be unaffected by the presence or

12 absence of dissenters’ rights.” § 13.02 at 1366. In

13 making this statement, the drafters were summarizing the

14 principles from the New York and Delaware cases that only

15 an equitable action may be brought under the exception to

16 the exclusivity provision of the appraisal statute, not an

17 additional claim for compensatory damages to supplement the

18 appraisal remedy. Grace v. Rosenstock, 228 F.3d 40, 50 (2d

19 Cir. 2000) (stating that New York only permits an

20 “appropriate” equitable action under the illegality or

21 fraud exception to the exclusivity provision).

22 In adopting the MBCA, which in turn adopted New York’s

23 exclusivity provision, our General Assembly confirmed that

24 the statutory appraisal remedy provides the dissenting

18

1 shareholder full and proper monetary recovery for the value

2 of its shares. Breed, 429 N.E.2d at 130. Additionally, by

3 adopting this special statutory proceeding which contains

4 strict deadlines and detailed procedures, the General

5 Assembly intended to allow corporations to continue with

6 business even though minority shareholders dissented from

7 the corporate action. In order to provide a speedy and

8 fair resolution, the legislature provided the appraisal

9 remedy. In doing so, it prevented dissenting shareholders

10 from challenging the corporate action based on the common

11 law, unless such actions were unlawful or fraudulent and

12 merit equitable relief. This construction of the exception

13 to the exclusivity provision conforms to the intent of the

14 General Assembly. § 7-113-102(4).

15

16

17

18

C. Application of the Dissenters’ Rights Statute

1. The Behrmann Trust’s Failure to Seek Equitable Relief

The Behrmann Trust argues that the officers and

19 directors engaged in self-dealing in connection with the

20 sale. Specifically, it argues that the officers and

21 directors negotiated their own employment agreements with

22 WBI, granted themselves benefits in connection with the

23 sale that created a conflict of interest, and withheld

24 information about the sale in the proxy notice.

19

1 The nature of the complaint is that the Behrmann Trust

2 would have been paid more money for the value of its shares

3 if the officers and directors had not breached their

4 fiduciary duty in connection with the sale of the assets.

5 However, having elected the statutory appraisal remedy and

6 not having sought equitable relief from the corporate

7 action, the Behrmann Trust has trigged the exclusivity

8 provision.

9 A dissenting shareholder may not seek

9 compensatory damages in addition to the appraisal remedy

10 when the complaint “boils down to nothing more than a

11 complaint about stock price.” Grace Brothers, Ltd. v.

12 Farley Industries, Inc., 450 S.E.2d 814, 821 (Ga. 1995).

13 The complaint in this case does not seek to rescind

14 the sale. Walter J. Schloss Assocs., 455 N.Y.S.2d at 852

15 (Mangano, J., dissenting opinion) (dismissing complaint

16 that alleged fraud and breach of fiduciary duty by majority

17 shareholder because “there [was] a fatal absence of any

18 primary request for equitable relief.”) (citations

19 omitted). Other forms of equitable relief might have been

20 injunction, reformation and rescission of instruments, and

9

The court of appeals held that the complaint alleged constructive fraud and thus fell within the exception to the exclusivity rule. However, it is not enough to plead a cause of action over which equity has jurisdiction; the dissenting shareholder must request equitable relief.

Walter J. Schloss Assocs., 455 N.Y.S.2d at 850.

20

1 specific performance of contracts. Id. at 851 n.4. The

2 complaint does not seek any of these.

3 We have long held that equity will not act if there is

4 a plain, speedy, adequate remedy at law. Hoffman v.

5 Colorado State Bd. of Assessment Appeals, 683 P.2d 783, 787

6 n.13 (Colo. 1984); People ex rel. Winborn v. District

7 Court, 87 Colo. 316, 323, 287 P. 849, 850 (1930). In its

8 compensatory damages action, the Behrmann Trust seeks to

9 receive additional compensation for the fair value of its

10 shares that it has already received in the appraisal

11 action. The statutory appraisal remedy provides an

12 adequate legal remedy for this cause of action.

13 2. Pre-existing Shareholder Claims

14 The Behrmann Trust filed this compensatory damages

15 action two days before it tendered its shares in PRC and

16 dissented from the asset sale. Because it filed the

17 compensatory damages action before it dissented, the

18 Behrmann Trust argues that the Act does not extinguish or

19 even address pre-existing shareholder claims. The Behrmann

20 Trust relies on section 7-113-204(2) for the proposition

21 that a dissenting shareholder retains the right to bring

22 fiduciary claims against directors and officers even after

23 the effective date of the proposed corporate action giving

24 rise to the shareholder’s right to dissent.

21

1 The officers and directors argue that section 7-113-

2 204(2) is plainly written to provide that a dissenting

3 shareholder gives up all the rights of a shareholder but

4 the right “to receive payment for the shares.” § 7-113-

5 204(2). The court of appeals agreed with the officers and

6 directors in this regard, holding that, although the

7 Behrmann Trust argued that it has an action separate and

8 distinct from the appraisal action, the “trust surrendered

9 its shares in PRC two days after it filed [the compensatory

10 damages action] and, thus, lost its right to sue for breach

11 of fiduciary duty through mismanagement of assets, self-

12 dealing, waste, or looting.” John R. Behrmann Revocable

13 Trust, 74 P.3d at 374. The court of appeals held, and we

14 agree, that under section 7-113-204(2), the appraisal

15 remedy provided the Behrmann Trust with an exclusive

16 remedy.

10

17 Section 7-113-204(2) states:

10

Despite this ruling, the court of appeals reversed the trial court’s order because it then held that the Behrmann

Trust’s complaint fell within the exception for unlawful or fraudulent conduct as to “actions unrelated to the sale.”

74 P.3d at 374. The court of appeals did not identify which allegations of the complaint assert such “unrelated actions.” In any event, the complaint’s recitation of corporate actions prior to the sale include the granting of bonuses and stock options to the officers and directors as events devaluing its shareholder interest, which is the subject of the statutory appraisal remedy.

22

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

A shareholder who demands payment in accordance with subsection (1) of this section retains all rights of a shareholder, except the right to transfer the shares, until the effective date of the proposed corporate action giving rise to the shareholder’s exercise of dissenters’ rights and has only the right to receive payment for the shares after the effective date of such corporate action.

§ 7-113-204(2) (emphasis added).

12 After the effective date of the corporate action, the

13 dissenting shareholder’s only right is to receive payment

14 for its shares. § 7-113-204(2); Breed, 429 N.E.2d at 129

15 (“When [shareholders] exercise the right under [the

16 appraisal statute] to have their stock appraised in a

17 judicial proceeding, they abandoned their alternative

18 rights as shareholders.”). This section, when read

19 together with the exclusivity provision, demonstrates that

20 the General Assembly intended to prevent dissenting

21 shareholders, who invoke the statutory appraisal remedy,

22 from maintaining compensatory claims in addition to the

23 appraisal action. § 7-113-204(2); Robert J. Brown, Jr.,

24 Colorado Corporation Law & Practice § 10.3 (1990) (once the

25 corporate action is effectuated, “dissenting shareholders

26 no longer have rights as shareholders, but have only the

27 right to obtain payment for their shares.”)

28 Thus, even though the Behrmann Trust filed its

29 compensatory damages action two days before it tendered its

23

1 shares, those pre-existing claims must be dismissed unless

2 they fall within the narrow exception to the statute’s

3 exclusivity provision. As discussed above, the Behrmann

4 Trust did not request an equitable remedy against the

5 corporate action as its primary form of relief. Thus, the

6 trial court properly dismissed its compensatory damages

7 action.

8

9

3. Action Against Directors and Officers

The Behrmann Trust argues that section 7-113-102(4)

10 does not bar its compensatory damages action because PRC is

11 not a party and this action is against the officers and

12 directors. The officers and directors argue that section

13 7-113-102(4) is not “a defendant-identifying provision that

14 applies only to suits against the corporation itself,” but

15 applies when the corporation is the alleged victim. Thus,

16 the officers and directors contend that the statute’s

17 exclusivity provision covers actions against the

18 corporation, officers, and directors. We agree.

19 The relevant section of the exclusivity provision

20 states that a shareholder entitled to dissent “may not

21 challenge the corporate action creating such entitlement

22 unless the action is unlawful or fraudulent . . . .” § 7-

23 113-102(4) (emphasis added). New York has always barred

24 claims against officers and directors under the exclusivity

24

1 provision if the complaint does not fall within the

2 exception.

3 In the New York Breed and Burke cases, the minority

4 shareholders brought an action against the directors of the

5 corporation. Burke v. Jacoby, 981 F.2d 1372, 1374 (2d Cir.

6 1992)(shareholder brought claims against the corporation’s

7 former president and board chairman, Robert Jacoby); Breed

8 v. Barton, 429 N.E.2d 128, 129 (N.Y. 1981)(shareholders

9 brought an action against individual, George Barton). In

10 both cases, the court held that the exclusivity rule barred

11 their claims. Burke, 981 F.2d at 1380-81; Breed, 429

12 N.E.2d at 131.

13 Similarly, in more recent New York cases where

14 shareholders brought actions against individuals, New York

15 courts have not distinguished between those claims and

16 claims brought against the corporation. Theodore Trust,

17 717 N.Y.S.2d at 7-8 (dismissing complaint against

18 individuals because a dissenting shareholder brought only

19 an action seeking money damages and the court held that the

20 exclusivity rule prohibited this); In re Lazar, 692

21 N.Y.S.2d 539, 540-41 (N.Y. App. Div. 1999) (permitting

22 dissenting shareholders to bring claims against directors

23 because their complaint sought equitable relief as its

24 primary form of relief).

25

1 The drafters of the MBCA adopted the New York formula,

2 and New York law is clear that the Act applies to actions

3 brought against officers and directors. Thus, the

4 statute’s exclusivity provision prohibits the Behrmann

5 Trust from bringing this action.

6

7

4.

Request to Amend Complaint

In this court, the Behrmann Trust argues for the first

8 time that we should remand the case to the trial court and

9 instruct the court to permit it to amend its complaint.

10 The Behrmann Trust alleges that its complaint put the

11 officers and directors on notice that it was seeking

12 equitable relief.

13 The Behrmann Trust could have amended its complaint in

14 the trial court under C.R.C.P. 15(a). See Davis v.

15 Paolino, 21 P.3d 870, 873 (Colo. App. 2001) (“For purposes

16 of this rule, a motion to dismiss does not constitute a

17 responsive pleading.”).

11 Because the Behrmann Trust seeks

18 to amend its complaint for the first time on appeal, we

19 will not grant the leave to amend its complaint. See

20 Fladung v. City of Boulder, 165 Colo. 244, 248, 438 P.2d

11

C.R.C.P. 15(a) states:

A party may amend his pleading once as a matter of course at any time before a responsive pleading is filed . . . . Otherwise, a party may amend his pleading only by leave of court or by written consent of the adverse party.

26

1 688, 690 (1968) (holding that the plaintiff was precluded

2 from raising the issue for the first time on appeal.) 12

3

4

III.

The complaint seeks compensatory damages in addition

5 to the statutory appraisal remedy it invoked against the

6 corporate action. When the Behrmann Trust elected to

7 dissent from the corporate sale, and obtain payment of fair

8 value for them, without seeking equitable relief from the

9 corporate action, it fell within the exclusivity provision

10 of the statutory appraisal remedy and not its exception.

11 Having surrendered its shareholder status, it may not, in

12 the guise of a suit against the officers and directors,

13 maintain a suit for pre-existing claims it may have had as

14 a shareholder. The trial court properly construed the

15 complaint in this action as alleging that a series of acts

16 preceding the sale of assets had the effect of devaluing

17 its shares; these are matters encompassed by the appraisal

12

In Delaware, even where rescissory damages have been timely sought in equity for breach of fiduciary duty, in addition to the appraisal remedy, delay in pursuing that relief can defeat the equitable claim. Ryan v. Tad’s

Enters., Inc., 709 A.2d 682, 698-99 (Del. Ch. 1996).

Because the Behrmann Trust did not seek an equitable remedy, we need not decide in this case whether Colorado, applying the exception to the exclusivity provision of the statutory appraisal remedy, might recognize rescissory damages as a remedy in addition to the payment of fair value for the dissenting shareholder’s shares.

27

1 remedy. Accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the court

2 of appeals and return this case to that court with

3 directions to reinstate the trial court’s dismissal order.

4

10

11

12

13

14

5

6

7

8

9

15

16

17

28