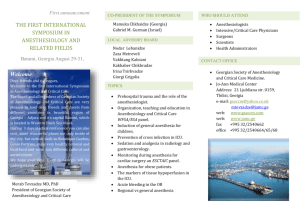

PROGRAMME - School of Medicine, Queen`s University

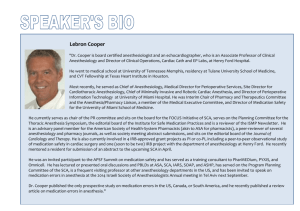

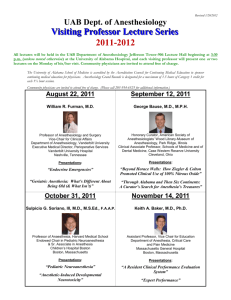

advertisement