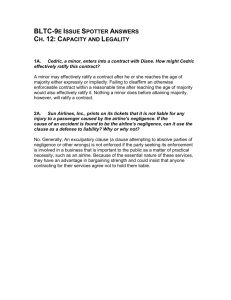

I. Intentional Torts

advertisement