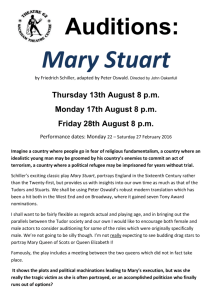

Mary Queen Of Scots handout

advertisement

Mary Queen of Scots The Troubled Life Of Mary There has always been a fascination about Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, cousin of Elizabeth I. Her life has been romanticized in novels and movies and her story is a great tragedy. Mary was a baby when she was crowned Queen of Scotland at Stirling Castle. She was the only legitimate child of James V, who died immediately after her birth. Not only was she Queen of Scotland, but as the granddaughter of Margaret Tudor, she had a claim to the throne of England after the children of Henry VIII. Mary was brought up at the French court as a Catholic and developed into a very accomplished and beautiful young woman, almost 6 feet tall, with beautiful dark red hair. At the age of 15 she was married to the dauphin (heir to the French throne) Francis, the son of Henri II of France. A few months after she went to France, Henry VIII's daughter, Bloody Mary Tudor, died childless and the English throne passed to Elizabeth. Upon the early death of her first husband, Francis II of France, in 1560, Mary became Queen Consort of France. Mary of Guise, the Regent of Scotland had died six months previously. The 19 year-old Mary therefore judged that it was preferable to be a Queen of Scotland than an ex-Queen of France and reluctantly returned to rule Scotland in 1561. Mary was a very high-spirited and impulsive woman, as well as a devout Catholic. There were bound to be problems when she returned to a Scotland which had embraced austere Protestantism in her absence. As reckless and impulsive as Elizabeth was shrewd and careful, Mary made one disastrous decision after the other, embroiling herself in scandal and political intrigue. An unmarried queen was an asset for any country. After the loss of her first husband and her return to Scotland, there was talk of Mary marrying Charles IX of France, the Duke of Guise, the son of Philip II and even the Protestant Eric of Sweden. Mary tried to arrange a marriage which would meet with Elizabeth’s approval since Mary was trying to remain her good graces so that she would name her as her heir. It soon became apparent that Elizabeth would oppose almost any match. Therefore, Mary chose her cousin Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Darnley was also a contender for the English throne and a Catholic. Mary was very much taken by his fine figure; they fell in love and were married without waiting for a dispensation from Rome (which they technically needed as they were first cousins) or for Elizabeth's approval. Mary was possibly still a virgin when she met Darnley, even though she had been married to the King of France. Undoubtedly, she had a strong sexual attraction to him. Darnley was a very ambitious young man, not too bright, who wanted to rule the country not as the consort of the Queen but as the King in his own right. He proved to be arrogant, ill behaved and untrustworthy. Mary by now was pregnant with the child who would eventually become James VI of Scotland and I of England. Because Darnley had proved such a disappointment to her, she turned her affections to an Italian, David Rizzio, whom she made her secretary. However, Mary’s feckless cousin and husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, soon became jealous of Mary's affections for her Italian secretary, and had him murdered in front of the heavily pregnant Queen. The following year Darnley was found strangled in the garden of his house which had been blown up. Only three months later Mary married the chief suspect in her husband's murder, James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell. Europe was scandalized, shocked more by the marriage than the murder, and the Scottish nobles forced Mary to abdicate in favour of her infant son, James VI. A great deal of deceit revolved around Mary and she had many enemies. Mary surrendered herself and was taken to Lochleven Castle. From there she was moved to Edinburgh, where she was met with jeers from the crowd and cries of “burn the whore”. Death by burning was the fate of a woman who murdered her husband. Fearing for her life, she was moved to Holyrood. Still the danger was so great that she was moved once again to Lochleven, where she was forced to abdicate in favour of her young son, who was hastily crowned at Stirling. She saw her son for the last time when he was ten months old. In 1568 Mary fled to England, seeking the protection of one Queen for another. However, she became Elizabeth's unwanted guest and prisoner for nearly two decades. Mary As A Threat To Her Cousin Elizabeth introduced moderate Protestantism to England with the Religious Settlement of 1559 in the form of the Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity. Despite the extreme displeasure which this created in the Catholic superpowers of France and Spain, for the first decade of her reign Elizabeth did not experience any significant problems at home from dissenting Catholics. However, the arrival of Mary Queen of Scots on English soil in 1568 changed everything. The governing class in England began to feel increasingly vulnerable to the Catholic threat which surrounded them in Europe. Though Elizabeth never met her cousin, she was continually suspicious of her and her French associations. It was also significant for Elizabeth that Mary had a son while she herself remained heirless. Elizabeth’s brush with smallpox in 1562 highlighted the significant concern that if she died childless and Mary succeeded her, the country would return to Catholicism. Because of her marriage to the Dauphin, Catholics believed that Mary Stuart had a better claim to the English throne than Elizabeth, and the King of France declared that she was the rightful Queen of England. Elizabeth was furious about the French putting forth a claim for Mary as the rightful Queen. Elizabeth was very jealous of Mary's beauty and feared greatly for her throne. Many Roman Catholics had never recognized the marriage of Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn and so for many, Mary was more than an heiress to the English Crown: she was the Queen of England. The deposed Queen of Scotland proved to be a destabilizing presence, as she quickly became a figurehead for disaffected Catholics. Plots and conspiracies abounded, the first taking place within a year of Mary's arrival in England. Although the Northern Rising of 1569, led by the Earls of Westmoreland and Northumberland, was crushed fairly quickly, it represented the first serious challenge to Elizabeth's authority and received the backing of the Pope. In February 1570 Pope Pius V issued a Papal Bull which excommunicated Elizabeth, “the pretended Queen of England: the Servant of Wickedness”. The Bull absolved her subjects from their oath of allegiance to her. It even included the penalty of excommunication for those who remained faithful to her. The Bull put English Catholics in an untenable position, with its declaration that a Catholic could not be loyal to both the Queen and the Pope, and its choice of penalties: treason or excommunication. More dangerously for Elizabeth, it authorised and legitimised the actions of the more extreme factions attempting to depose her. From 1574 onwards, Jesuit priests who were happy to give up their lives for their Catholic cause, began arriving in England. It was of great concern to Elizabeth that these Jesuits found converts in the English population, whose loyalties lay in Rome rather than with their Queen. The Plot Thickens One of the most significant plots against Elizabeth was the Ridolfi plot, planned by Roberto Ridolfi, a Florentine banker living in London. Uncovered by Walsingham and the government in 1571, the conspiracy aimed to use Spanish troops from the Netherlands to depose Elizabeth and put Mary on the throne, with Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, as her husband. Norfolk was found guilty of treason and executed in 1572, after Elizabeth stayed his execution three times. Although Mary was implicated in the plot, Elizabeth refused calls for her to be put on trial. This stubborn refusal continued during the Throckmorton Plot of 1583. The next pope, Gregory XIII, elected in 1572, advocated an even more extreme antiProtestant stance than his predecessor, and encouraged numerous schemes to invade England, depose and even assassinate Elizabeth. Mary became the focal point of so many conspiracies to remove Elizabeth that the Privy Council and Parliament frequently pressed Elizabeth to put Mary to death. Elizabeth, however, remained reluctant to execute a fellow monarch. It was the plot hatched by Anthony Babington, a rich Catholic, to kill Elizabeth and start a Catholic uprising which was to be Mary's undoing. In July 1586 Babington wrote to her to inform her that he had six friends “Who for the zeal they bear unto the Catholic cause and your Majesty's service will undertake that tragical execution”. Mary replied to Babington: “Then shall it be time to set the six gentlemen to work, taking order upon the accomplishment of their design”. Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth's Secretary of State and spymaster, had already infiltrated Mary's network and was monitoring her correspondence. He intercepted the letters hidden inside beer barrels and deciphered her code. Mary's reply sealed her fate. It provided the proof Walsingham needed to finally convince Elizabeth to have Mary arrested and put on trial. She was arrested on 11 th August 1586 and brought to trial in October. With reams of evidence against her, Mary was found guilty of being 'not only accessory and privy to the conspiracy but also an imaginer and compass of her majesty's destruction'. Off With Her Head While Parliament urged Elizabeth to sentence her cousin to death, Elizabeth agonised and prevaricated for another four months, before finally signing Mary's death warrant. Mary was eventually executed on 8 th February 1587 at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire. It was a cold and bitter winter's day when Mary, with dignity intact, was led to the block. She wore a black cloak with a white veil over her head. When she reached the block, she dropped her cloak and revealed a crimson dress. Her last words were “Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit”. True or not, the story is that when her head toppled, her body began to move, frightening everyone present. It was found that her little dog had been hidden within the folds of her dress. All that Mary took with her to her execution, her crucifix, writing book, bloodstained clothes and even the block, were burned; there were to be no relics of the pretender to the throne. When the executioner held up Mary's severed head, the wig that she wore fell off, and she was revealed to be an old woman, with white hair and partially bald. The Aftermath Elizabeth felt duped by her advisers, who had urged her to execute her cousin, and was angry that the execution had taken place at all. Indeed, the Privy Council had laboured for many years to overcome Elizabeth’s obstinate refusal to kill Mary Stuart. As Smith argued, the Privy Council, and the Lords and Commons, essentially had to wring the death warrant from a reluctant Elizabeth and they had to pay the price for that in the aftermath of the execution. The Queen demonstrated her anger and punished those who carried out the order. The threat of Mary Queen of Scots had been eliminated, but the threats to the Crown from Catholic forces had not. Catholic Europe was outraged by the regicide of a Catholic monarch, and Mary's execution played its part in convincing King Philip II of Spain to send the Spanish Armada to invade England. The English governing class was satisfied that a potential security threat had been removed. English Puritans were extremely happy with the execution, since they saw it as another step away from the threat of Rome. Catholics, however, were arguably marginalised in society by the execution and the suspicion which hung over them. Mary’s infant son, James, was left as the strongest legitimate claimant to the English throne. Indeed, he became James I of England in 1603 after the childless Elizabeth died.