MEDIEVAL ART in the North

advertisement

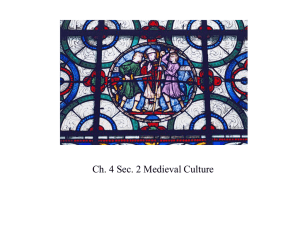

1 Introduction to Humanities Michael Jhon M. Tamayao, M.Phil. Lecture Notes on: MEDIEVAL ART in the North (400-1400) Barbaric or Civilized? European Medieval art is typically divided into six periods: Early Christian art (100-500), Byzantine art (500-1453), Celto-Germanic art (400-800), Carolingian art (750-987), Romanesque art (11th – 12th centuries), and Gothic art (overlapping the Romanesque in the 12th century and extending in some areas into the 16th century). The first two are considered the “southern or Mediterranean” branch of medieval art, while the latter four are considered the “northern”1 branch. The latter branch includes areas like France, Germany, Scandinavia, Netherlands, Belgium, and the British Isles. Many attribute “barbarism” to this “northern” branch because it is beyond the urban cultural ambit of the Mediterranean world.2 As a matter-of-fact, northern medieval art started with the “barbaric” art of the Celto-Germanic people and developed only when the influence of Christian art was brought to north by missionaries from the south. Many understand the label “Medieval” or “Middle Ages” as the gloomy transitional period between the decline of Rome and the beginning of the Renaissance. As far as output is concerned, we cannot just consider this period as a “barren transitional period” because it obviously has its own stylistic influence, identity and originality that devoted its greatest effort in the service of Christianity. In our past discussion of Early Christian and Byzantine art, we said that it revolved around the iconoclast-iconophile clash, thus, subdividing the time to the iconoclastic and iconophilic periods. Northern medieval art, on the other, also gyrates around two different, but nonetheless non-opposing, periods: the monastic and secular periods. Celto-Germanic, Carolingian, and Romanesque art are under the monastic period because their art developed mainly in monasteries. Gothic art, on the other, is under the secular period because its art developed in the more urban cathedral3 centers of secular clergy4. Monasteries and cathedrals are therefore the two main catalysts for the development of northern medieval art. Just as religion is the impetus for the proliferation of art in the medieval mediterranean areas, Christian monasticism and secularism are considered the main factors for the artistic propagation in northern medieval Europe. 1 Although “Western” Europe is distinct from “Northern” Europe, this article will use “northern” in place of areas above the Mediterranean coasts. France and the British Isles, which are located in Western Europe, will therefore be under northern for the purposes of the paper. 2 It should be well noted that the development of the great Greek and Roman civilizations transpired in the Mediterranean area so that places outside their dominion are considered savage, uncivilized or barbaric. 3 Cathedral came from the word “cathedra” which means the throne of the bishop that is placed in the main church of the diocese. 4 A secular clergy is a clergy who did not withdraw from lay society in contrast to monks who withdrew from the materialism of lay society and embraced rigid monastic rules. 2 I. Celto-Germanic and Carolingian Art (400-987) The indigenous and insular art of northern Europe are embedded in CeltoGermanic Art (CGA). CGA combines lively, intricate, geometric, spiral and abstract designs with fantastic animals and human forms.5 The style is generally characterized as flat. There is no illusion of mass and space as vividly seen in the period’s metal works and paintings. Metal works, such as bracelets, armbands, swords and purse covers, are usually made of bronze or gold decorated enamel. However, the style of CGA slowly changed under the influence of Byzantine paintings brought from the south by missionaries. The illuminated manuscripts of this period, such as the Book of Kells, exemplify a mixture of the CG design and the relatively static and symbolic Early Christian and Byzantine art. By 750, CGA merged with the Carolingian period, which eventually led to its absorption into the latter. Illustration 1: Details from the Book of Kells (8th cen., 12 5/8” x 9 ½. Trinity College Library Dublin) Details from the Book of Kells (8th cen., 12 5/8” x 9 ½. Trinity College Library Dublin) Although Carolingian art is distinguished from CGA, it is still deeply affiliated to the insular art of northern Europe. It must be well noted that the then reigning Carolingian monarchs, spearheaded by Charlemagne, have their roots in the barbaric bloodline of the Franks. It was only through the coronation of Charlemagne as the great and pacific Emperor of Rome that the term “Carolingian” acquired a “civilized” connotation. Carolingian Europe was poor. It was based only on a rural and survival economy.6 The ‘threat of Moslem invasion in the south and east Mediterranean’ and the ‘rampant vandalism and kidnappings of the Vikings in the north’ accounted for the tremendous severity of the period. Although during 5 Dale G. Cleaver. Art: An Introduction (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc., 1977), p. 151. For a more detailed elucidation of Carolingian Europe, confer to the site: www.historicalstudies.unimelb.edu.au/bernardsmith/lectures/BSmith-Caroligian1.pdf. 6 3 Charlemagne’s reign there was already moderate stability in Europe, militarywise and economic-wise, the great havoc brought forth by the foreign invaders left Carolingian Europe groping in the dark. Charlemagne thus set himself to restore religion, education, and culture. He did this by building monasteries, which served as both a place of worship and a place of education. Even his palace was constructed for the same purposes. In Charlemagne’s palace-school, manuscripts were written and illuminated, such as the gospels, book of hours, translations, and new copies of the writers of antiquity. Aside from the palace school, Benedictine monasteries also contributed much of the same works. For this reason, Charlemagne supported the development and growth of this monastic order. Illustration 2: Ebbo Gospels (Gospel Book of Archbishop Ebbo of Reims). c. 816-835. Saint Matthew. Approximately 10 x 8" Driven by the goal of propagating faith and education, the Carolingian king and his throne often move from centre to centre. This explains why the greatest art treasures of the time (such as the illuminated gospels and book of hours, ivories for portable shrines, portable altars, reliquaries with relics of saints, gold chalices, crosses, patens, and the like) were “small” and “portable”. Many small and simple churches were also built for the purpose of introducing Christianity to the region. This period made extensive use of wood most especially in building houses and small parish churches. Carolingian builders used stone only for important buildings, such as the large basilicas, through which Charlemagne ennobled his reign, and special tombs of saints and founders of the church. The Carolingian churches also had two styles rooted from Roman architecture: the longitudinal (Basilica) and central churches. The central churches show Byzantine influence in their form and decorative details. The Basilicas, on the other, are typified by timber roofing and many towers. 4 Illustration 3: Restored Plan of the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne Illustration 4: Interior of the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne, Aachen, 792-805. The finest artistic remains of Carolingian art are of course the illuminated manuscripts with which Charlemagne and his successors sought to Christianize, educate, and revive the glories of ancient Rome.7 II. Romanesque Art (1000-1200) The term “Romanesque” is literally understood as “Roman-like” attributive to the 11th and 12th century art. And indeed, when we say “Romanesque art” it is an art period that made use of Ancient Roman style, such as massive walls, 7 Ibid. 5 vaults, engaged columns, and palisters. But although the label “Romanesque” is useful it is also misleading. Medieval sculptors and architects of “Romanesque” France and Spain did not just copy Roman art, they have a first hand knowledge of it. Remember that Spain and southern France were heavily laden with Roman infrastructures during the Roman period. In which case, subsequent sculptures and architectures in these areas should not simply be considered as imitations; they are still within the authentic Roman stylistic repertoire. Illustration 5: Interior of St. Sernin, Toulouse (View towards apse) Illustration 6: West facade of St. Etienne, Caen, begun c. 1067. 6 The label “Romanesque” also disregards the other influences of the period. While emphasizing the dependence on Roman art, the label ignores the other two formative influences on Romanesque art, the Celto-Germanic art and the Byzantine art. For one, the combination of the impulsive insular art of the Celto-Germanic people (Anglo-Saxon), on the one hand, and the flat symbolic art of Byzantium in the 6th century Illuminated Manuscripts, on the other hand, still lingered in Romanesque French illuminations. Like the Anglo-Saxons, French illuminators created a lavish surface decoration combining interlaced ribbons with animal motifs.8 Furthermore, the label does not also do justice to the inventiveness of Romanesque art. Some of the significant changes that transpired in this period include masonry building (in contrast to the predominant use of concrete construction), and use of “ribbed” cross vaults in contrast to the standard Roman cross vaults.9 Illustration 7: Interior of St. Etienne, vaulted c. 1115-20. Sculpture-wise, Romanesque is a combination of Celto-Germanic art, Roman art, and Early Christian and Byzantine art. In contrast to Carolingian art, which preferred Byzantine miniature sculpture, Romanesque art revived monumental sculptures. Most of these monumental sculptures are found on churches. But painting-wise, Romanesque is very similar to Carolingian. Although it has a 8 But instead of merely filling the space, the interlace illuminations has its own rhythm, reinforced by more vibrant colors. See: www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rmsq/hd_rmsq.htm. 9 Cleaver, p. 154. 7 general tendency towards flat shapes, it has more dynamic lines than that of Byzantine paintings. Illustration 2: Bishop Bernward. Adam and Eve Reproached by the Lord, from the bronze doors of St. Michael's, Hildesheiiim, c. 1015. Approx. 23" x 43". We can summarize 10 characteristics : Romanesque architecture with the following 1. Fortress-like massiveness 2. Roman arches; see illustration 9 and 11. 3. Two or more towers; see illustration 10. 4. Splayed openings – two or more windows formed by layers of increasingly smaller arches producing a funnel of effect 5. Blind arcades – arcades attached to the buttressing rather than to create openings walls for decoration or for 6. Corbel tables – a stringcourse (horizontal band or molding) supported by a row of continuous small blind arches (Lombard) or by small brackets projecting from the walls (French); see illustration 8. 7. Wheel windows – round windows divided into sections by stone dividers radiating from the center like the spokes of a wheel. 10 Ibid., pp. 154-155. 8 Illustration 9: Corbel tables (French) Illustration 10: Interior of St. Ambrogio. Illustration 3: East facade of Durham Cathedral, eleventh and twelfth centuries. 9 Illustration 4: Interior of Durham Cathedral III. Gothic Art (1150-1400) When we say Gothic art, we usually refer to Gothic churches which are characterized by their height, open walls, and complex linear designs that are all integrated to the vast medieval theological symbolism. Architecture was the most important and original art form that served as the main instrument for accomplishing the religious ideals of the time. France pioneered this form of architecture in the mid-twelfth century. The French cathedrals, for example, were considered complex symbols for the City of God.11 The spiking height emphasized by the heavily vertical lines of the churches, the intricacy of religious designs, and the openness of walls, which catered more extensive iconographies in stained glass windows, were all means to express medieval theology. 11 Cleaver, p. 165. 10 Illustration 5: West façade of Amiens Cathedral. Illustration 64: West facade of Salisbury Cathedral, begun c. 1220. 11 In a similar point of view, Gothic cathedrals were, in themselves, considered “microcosms”12. They show this in two ways: first, by reflecting the orderliness of the universe through the mathematical and geometrical nature of their construction; and second, by revealing the divine plan of God for men through their elaborate sculptural decorations, murals, and stained glass windows which all incorporate stories from the Bible.13 Illustration 15: Vierge Doree (Golden Virgin), from the south transept trumeau of Amiens Cathedral, c. 1250-70. Illustration 16: The Last Judgment, from the central portal of the west facade of Amiens Cathedral, o. 1220-30. 12 13 Microcosm; “micro” means small, and “cosmos” means world or universe. Cf. www.enwikipedia.org/wiki/Gothic_architecture 12 Illustration 7: St. Theodore, from the south transept portal of Chartres Cathedral, o. 1215-20. Another way of understanding the principal features of Gothic art is by understanding its development. According to historians, it arose out of medieval masons’ efforts to solve the problems associated with supporting heavy masonry ceiling vaults over wide spans. The traditional barrel and groin vaults exerted tremendous outward and downward forces on the supporting walls on which they rest. This was why periods preceding Gothic architecture built massive walls to support the heavy roofs of their buildings. Although some Romanesque builders made use of “ribbed” vaults, which minimized both the weight and the tremendous forces that threatened to collapse the buildings, it was the Gothic builders who utilized the “ribbed” vault to its utmost use. Instead of the “round ribbed vaults”, Gothic builders constructed “pointed ribbed arches” which accordingly distributed thrust in more directions downward and thus enabled the builders to construct thinner walls, and even opened with large windows. As Wim Swaan states: “… due to the versatility of the pointed arch, the structure of Gothic windows developed from simple openings to immensely rich and decorative sculptural design. The windows were filled with stained glass which added a dimension of color to the light within the building, as well as providing a medium for figurative and narrative art.”14 14 Wim Swaan. The Gothic Cathedral (Omega Books, 1988). 13 Illustration 18: Notre Dame, Paris, 1163-1250. Aside from the ribbed vault mechanism, Gothic architecture is also known for its “flying buttresses.” (See Illustration 18) These are half-arch freestanding priers which function as the ultimate absorbent of the ceiling vault’s outward and downward thrusts. Coupled with the “ribbed” vault mechanism, the use of flying buttresses enabled the Gothic masons to build much larger and taller buildings than their Romanesque predecessors and gave their structures more complicated ground plans.15 Through the Gothic architectural innovations, “light” became an indispensable part of construction. The possibility of huge openings on the walls, made possible by the pointed ribbed vaults and the flying buttresses, added great amount of illumination inside the buildings, thus, highlighting even more the theological inscriptions of the interior. After all, light in medieval theology was a symbol for God.16 15 16 Encyclopedia Britannica Cleaver, p. 165. 14 Illustration 198: Giotto, detail from Lamentation at the Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua. Illustration 90: Duccio, Christ Entering Jerusalem. detail from the Maesta Altarpiece. 1308-11. Siena Cathedral. Illustration 101: Duccio, Maesta Altarpiece, 1308-11: Annunciation of the Death of the Virgin 15 Simple Art Notes Among all the different art periods, Medieval Europe, most especially the Gothic period, poses as one of the best stages in architectural development. As clearly seen in the various religious infrastructures (Cathedrals, Basilicas, Shrines, and Squares), Medieval Europe has exceeded the preceding periods in terms of the grandness and sophistication of their architectural outputs. Although it has started as a barbaric culture, Northern Europe progressed into a breathtaking abode of otherworldly edifices. And it was through Religion that culture and education was reestablished. Now if you still think that Medieval Europe is gloomy, think again. Sources Cleaver, Dale. Art: An Introduction. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc., 1977. Evans, Joan. Art in Medieval France. Oxford, 1948. Penofsky, E. Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism. London, 1957. Saalman, Howard. Medieval Braziller, 1962. Architecture: European Architecture, 600-1200. New York: Swaan, Wim. The Gothic Cathedral. Omega Books, 1988. Witzleben, Elizabeth von. Stained Glass in French Cathedrals. Trans by Francisca Gravie. New York: Reynal, 1968. Britannica Encyclopedia http:/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanesque_art www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rmsq/hd_rmsq.htm www.historical-studies.unimelb.edu.au/bernardsmith/lectures/BSmith-Caroligian1.pdf.