alltrials campaign - SABRE RESEARCH UK

advertisement

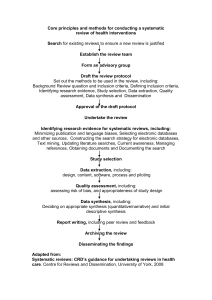

Missing animal trial data - briefing notes Non-disclosure Research has shown that about half of all pre-clinical animal trials (medical studies or experiments using laboratory animals) have not been published.1 This is called 'publication bias' and considered very bad practice in science. It happens in clinical research too. By not disclosing all of the animal data (information from the animal trials) it presents a partial and distorted picture of the evidence used to support decision-making in the translation of animal research to human research. The information from clinical and pre-clinical trials is assembled in large databases, libraries and other repositories and is collectively known as the 'evidence-base'. Not disclosing or withholding access to evidence is implicated in the drug attrition rate2 (where drugs fail to get marketed), and any such failures in medical research directly affect patients and research volunteers and wastes funding. Academia and pharmaceutical companies are at liberty to conduct animal and clinical trials on a drug or treatment but then only publish the results that they choose to. It follows that they are more likely to publish those results that look favourable to their own research objectives. There are some competitive pressures on researchers to present only their positive findings (results) and they believe positive findings are more likely to get published in big important medical journals. The more publications researchers get their name into the more research funding they generally receive.3 But these personal and financial pressures should not be allowed to bias research or be used as an excuse for pre-clinical non-disclosure. There are now open access and other journals where researchers can publish their results regardless of the outcome of the research. It is vitally important that all these results are published and not just the cherry-picked ones (selectively chosen ones) because it is the information presented as a whole that is important regardless of whether the result was positive (the result you wanted or expected), negative (the result you didn't want or expect), null (a result that did not support your hypothesis) or inconclusive (no really useful information that you could proceed with). All the information is important. It is like giving someone a jig-saw puzzle with lots of pieces missing and expecting them to know exactly what the complete picture looks like. No scientific result should be regarded as worthless, (assuming the research has been carried out rigorously and set in the context of other research - see paragraph on systematic reviews) because we need all the information to progress science and know what works and what doesn't. 4 Prospective registration So that the public and researchers can see that all animal research is published there needs to be a register of animal trials just like there is for clinical trials at clinicaltrials.gov. 2 5 It should be noted here that in spite of there being a clinical trials register not all clinical trials are recorded on it. Legislation is therefore needed to ensure that all animal and clinical trials are registered. Each trial to be carried out should be registered prospectively (beforehand) so that it can be gauged whether the results were published or not and then appropriately followed up. With legislation this is the only way that a curb can be put on the withholding of animal data. It means that academia and the pharmaceutical industry cannot carry out animal experiments and then not disclose the results if they don't like them or only publish them if they look good. It should also be required that all existing and historical animal results are disclosed and placed into a database in order to avoid the waste of funding which occurs because researchers are unnecessarily repeating experiments that have already been carried out. When the evidence-base is lacking in some of the information from research (animal and human) it creates large gaps in knowledge. And it is now realised that this leads to unreliable decision-making. Investigators (trial researchers) who use the animal data for designing human research, the reviewers who assess that research and the doctors who then make decisions about treatments for their patients do not have the best and most reliable evidence at their disposal. This in turn means that their decisions have the probability to cause harm to research volunteers and patients. There is one extreme example of this in the TGN1412 trial where Phase 1 research volunteers were exposed to a seriously harmful and dangerous clinical trial that could have been avoided if all the animal and human research had been registered and made openly accessible and systematically reviewed beforehand.6 Systematic reviews Good systematic reviews are critical appraisals of research that aim to remove as much bias from the review of the research as possible. They set the research in context with other relevant research and aim to identify, evaluate and summarise the findings of the research making the evidence more accessible to decision-makers. 7 It was first reported in February 2002 in the BMJ that systematic reviews and metaanalyses (statistical and mathematical calculation of research results) of animal studies are scarcely used in the evaluation of animal research.8 The authors found that while about 1 in 1,000 Medline (big medical database) records referring to human research is tagged (identified) as a meta-analysis, only 1 in 10,000 records is tagged similarly for animal research. This disparity suggests that a systematic and comprehensive analysis of animal research is considered less important than it is for clinical research. However, a commentary in the Lancet, in the same year, called for systematic reviews of animal studies to be made a prerequisite to all clinical trials that are based on animal data,9 and in 2004 an Education and Debate paper in the BMJ called for prospective registration of animal trials and a large-scale programme of systematic reviews of animal research to assess the relevance of animal studies to human health.10 These requirements are still far from being widely implemented in spite of a report by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics recommending that more systematic reviews of animal research are needed.11 Systematic reviews (SRs) of all the available relevant animal and human research should always be carried out before new research is approved and funders should always require one before granting research funding. However, SRs are only as good as the data from which they are derived and it is only by making animal trials transparent and publicly available through prospective registration and 100% publication rate that reviewers can analyze and assess the research with the level of accuracy that the public should expect. For further information about systematic reviews Sense About Science have produced a fact sheet called Sense About Systematic Reviews. 12 Solutions To overcome the problems of missing data and its negative consequences there are solutions which we have referred to above (prospective registration of all trials and systematic reviews). However, the public should be aware that regulators, academic institutions, and industry are resistant to changes and have, for decades, persistently raised objections to these improvements that would otherwise help protect research volunteers and patients from unsound research. For too long research has been allowed to go 'forging ahead' blindly based on incomplete evidence 'and predictions of dubious reliability' for the sake of commercial interests.13 It is only the public's awareness and support that this issue of bad science will ever be resolved in a timely manner. "The public needs to be made aware of how the resources they provide for research are being wasted and they need to hold the research community to account, and be critically involved in research, from agenda setting to dissemination of results." (Iain Chalmers, PowerPoint presentation at the Involve Conference, November 2012). Please sign the petition to make all animal and clinical trials (past and present) registered and the full methods and results reported so that medical science can start to improve. Trials will be made safer for research volunteers and medicines and treatments more reliable and effective for patients with less funding wasted. Please ask your doctor to sign too. Thank you, on behalf of the charity SABRE Research UK. 1 ter Riet G, Korevaar DA, Leenaars M, Sterk PJ, Van Noorden CJF, et al. (2012) Publication Bias in Laboratory Animal Research: A Survey on Magnitude, Drivers, Consequences and Potential Solutions. PLoS ONE 7(9): e43404. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043404 2 Kimmelman J, Anderson JA, Should preclinical studies be registered? Nat Biotechnol. 2012 Jun 7;30(6):488-9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2261 3 Fanelli D (2010) Do Pressures to Publish Increase Scientists' Bias? An Empirical Support from US States Data. PLoS ONE 5(4): e10271. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010271 4 Evans I, Thornton H, Chalmers I, Testing Treatments: Better Research for Better Healthcare. British Library, London, UK, (2006) 5 Sena ES, van der Worp HB, Bath PMW, Howells DW, Macleod MR (2010) Publication Bias in Reports of Animal Stroke Studies Leads to Major Overstatement of Efficacy. PLoS Biol 8(3): e1000344. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000344 6 Kenter MJ, Cohen AF. Establishing risk of human experimentation with drugs: lessons from TGN1412, Lancet. Oct 14;368(9544):1387-91(2006) 7 CRD York, Systematic Reviews http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf accessed 14/01/13 8 Roberts I, et al. Does animal experimentation inform human healthcare? Observations from a systematic review of international animal experiments on fluid resuscitation BMJ. Feb 23;324(7335):474-6 (2002) 9 Sandercock P, Roberts I. Systematic reviews of animal experiments. Lancet. Aug 24;360(9333):586 (2002) 10 Pound P, et al. Where is the evidence that animal research benefits humans? BMJ Feb 28 328; (7438) 514-517 (2004) 11 Nuffield Council on Bioethics, The Ethics of Research Involving Animals. Nuffield Council on Bioethics, London (2005) 12 http://www.senseaboutscience.org/data/files/resources/52/Sense-About-Systematic-Reviews.pdf 13 Kimmelman J, London AJ (2011) Predicting Harms and Benefits in Translational Trials: Ethics, Evidence, and Uncertainty. PLoS Med 8(3): e1001010. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001010