This paper was written in partial fulfillment of English 401, C

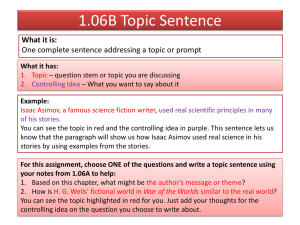

advertisement

This paper was written in partial fulfillment of English 401, C. S. Lewis: the Legacy of His Poetic Impulse, at Montreat College in Spring 1997. Chris Howard retains copyright privileges; those wishing to use material from this essay may do so as long as Chris Howard is given appropriate recognition. Chris Howard May 2, 1997 Dr. King EN 401 C. S. Lewis and Issac Asimov: A Comparison and Contrast of the Men, Their Minds and Literature. Two of the most widely read authors in this half of the century come from very different backgrounds but both gained critical acclaim and popular recognition as accomplished science fiction writers. Clive Staples Lewis and Isaac Asimov have both contributed to the rapidly developing and steadily growing genre of future times and other worlds. Lewis was very well known for his story of conversion from atheism to theism and finally to Christianity as well as his Christian apologetics. However, Lewis also wrote in other genres. His total literature falls into various categories including poetry, myth and science fiction. His best known science fiction works were the three novels of his Ransom Trilogy: Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra and That Hideous Strength. Asimov, born Russian and a naturalized American, also wrote in a diverse array or genres. His work ranged from science textbooks and essays to reference guides and dictionaries for the Bible, but he focused primarily on science fiction. Asimov's most celebrated series is the Foundation trilogy. Technically it is a quintilogy, but the fourth and fifth volumes were written and published in the eighties while the original trilogy was written and released in the late forties and early fifties. Due to the intermission between the two chapters of the saga, critics focus on the primary trilogy and concluding two separately. Lewis and Asimov were born within twenty-five years of each other and both spent most of their lives in a nation other than the one they were born in. They also both received massive amounts of education. Other than that, they share very little in common. If anyone reads both the Space and Foundation trilogies, they might expect that Lewis and Asimov were similar authors, but taking a deeper look at the two reveals many differences. This paper is such a look and it appears that the difference between them is due to one being a scholar of literature and the other a scientist. The differences between these two reading giants include their the writing styles of their science fiction, literary views on humanity as a fallen race, the semifictional science of psychohistory, man's relationship with a machines and finally a comprehensive analysis of their views on modern technology. The topics discussed in the arena of modern science and technology include the benefits of advanced living, the disadvantages and costs of maintaining a highly technological civilization, possible solutions to the costs of maintaining such a civilization, the theory of evolution and science's effect on the beauty of Earth. Before comparing and contrasting the two authors, a brief synopsis of their lives and place in literature might prove insightful, as Lewis's and Asimov's backgrounds no doubt had a tremendous effect on their writings and mindsets. Clive Staples Lewis was born in Belfast, Ireland on November 29, 1898. He served in the British Army during World War I, achieving the rank of second lieutenant. After the war, he completed his education and became a lecturer and professor of medieval and Renaissance literature. He married in 1956 when he wed Joy Gresham Davidman. Four years into the marriage, she died. Lewis followed three years later, ironically on the same day the President Kennedy was assassinated (Locher 328). Lewis was close friends with Charles Williams and J. R. R. Tolkien, two other early writers recognized to have influenced modern science fiction. Other fantasy-oriented fiction of Lewis has been acknowledged either as science fiction or more commonly as containing science fictional elements. These elements include time travel, alternate dimensions and parallel worlds, primarily in his Narnian chronicles. It was, however, the Ransom Trilogy that was his main contribution to the mainstream of the genre (Nicholls 353). Issac Asimov was born in Russia in 1920, but his parents smuggled him in their luggage into the United States at the age of three. He was naturalized as a citizen in 1928. He earned a major in chemistry from Columbia University in 1939 and went on to earn a master's in 1941 and a Ph.D in 1948. He also served in the United States Army during World War II. He was hired by the Boston University School of Medicine. He became associate professor for biochemistry, a title he retained even after his resignation in 1958. He then pursued a fulltime writing career, as his part time writing had been a successful and profitable pastime for nineteen years at the time. Once married to a Gertrude Blugerman, he spent most of his years with his second wife Janet Jeppson, a psychiatrist who with Asimov and later independently became a science fiction writer herself, primarily known for her fiction for children. He is best known for innovative works such as "Nightfall" which has been dubbed as the best science fiction short story of all time by the Science Fiction Writers of America and his introduction of the three Robotic Laws. The Hugo and Nebula awards are two of the crowning achievements in the genre and Asimov is a multiple winner, in part due to his Foundation series (Nicholls 49). The writing styles of Lewis and Asimov were just one of many differences between them. Even though Lewis considered his Space Trilogy a fantasy or modern fairy tale, one reviewer disagreed. Citing That Hideous Strength especially, the reviewer wrote that Lewis "uses the scientific method as a means of defining and identifying the extrahuman beings functioning" in the Space Trilogy. Lewis used science as a cohesive element in the third installment of the saga and "that places the novel in the tradition of hard science fiction"(Lowenberg 235). Donald Watt praised Lewis's use of point of view in Out of the Silent Planet by admiring the "vivid and comprehensive view of the Malacandrian hierarchy" and "a critical perspective on human beings from the Malacandrian point of view" (57). Lewis's use of language has also been praised. Kath Filmer was impressed by Lewis's use of figurative, symbolic and metaphorical language: "Lewis's images and metaphors depict the immanence of God, the reality of human corruption, and the cosmic battle between good and evil" (219). On the other hand, Joeseph F. Patrach, Jr. probably summed up Asimov's style best. Rather than the eloquence and elaborate description employed by Lewis, Asimov's simplicity lies in "the typical Asimov sentence" which "is short and clear...They gain length not by the accumulation of dependent clauses, but by the addition of [more] simple sentences. He does not like to use figurative language so he almost never uses images, metaphors, similes." (Gunton 24). Asimov himself explained his simple style's: "I type quickly-90 words a minute, when I am happy, carefree and in a good mood." He added "I don't believe in fancy stuff. In my writing, there is no poetry, no complexity, no literary frills. Therefore, I need only barrel along, saying whatever comes to mind, and waving cheerfully at people who happen to pass my typewriter" (Asimov, Roving Mind 337). His simplicity had the advantage of fueling his prolific production. At one point in his more than four hundred book career, he published 141 books in 138 months, after which he humorously declared "I am a one-man book of the month club" (338). Any reader of this comparison of Lewis and Asimov has probably had the pleasure of reading the Space Trilogy, but if it has been a while since that time, the following is a quick summary. In Out of the Silent Planet, Dr. Ransom was abducted by human captors and taken to Malacandra. After he escaped, he lived and learned among the three hnau: the horossa, the seroni and the pfifltriggi. He eventually met Oyarsa, the planet's eldil and returned home. In Perelandra, Ransom again traveled to a new world. This time it was Venus rather than Mars, and he also traveled of his free will. Ransom here tackled an agent of Satan who tried to tempt the planet into following Earth's footsteps into corruption. In That Hideous Strength, Ransom battled the organization of N.I.C.E., which was attempting to create a superior race of men whose heads were kept functioning by artificial means. The organization was also attempting to rid the Earth of all supposed imperfection by replacing all animals and plants with controllable replicas. Students and/or researchers of Lewis are likely to be less familiar with the works of Asimov, so the following is a brief account of the setting and purpose of the Foundation trilogy, but it reveals nor spoils very little of the thousand year plot line should one want to read them. The opening premise is that a Galactic Empire will rule the quadrillions of humans on the roughly twenty-five million inhabited worlds for tens of thousands of years. Psychohistorian Hari Seldon will foresee the Empire's collapse and through psychohistory predict a period of chaos and misery spanning thirty millennia before a second empire would be established. He created two Foundations, the first grand and public, the second subtle and secret, of scientists at opposite ends of the galaxy. Through superior mathematics, science, technology, economics and their private conclusions from psychohistory, the two Foundations would collect and reintegrate the remnants of the First Empire to reduce the interval between governments to a single millennium before a more stable and just Second Empire was formed (Asimov, Second Foundation vii). Both Lewis and Asimov recognized that humanity possessed the status of a fallen race. Lewis's views were very prevalent in his trilogy, especially in Out of the Silent Planet and That Hideous Strength. In the first novel, Earth's evil was illustrated by comparison with and from the perspective of Malacandra's good. Peter Macky stated that "Malacandra has no inherent evil" and that the theme is "moral collectivism versus...individualism" (Lowenberg 206). Janice Witherspoon Neulib stated that Lewis used "the shining brilliance of goodness to show his grotesques for the parody of fallen humanity that they are" (151). Asimov's works also dealt with the fall of man. The Foundation trilogy had its settings created by the fall of "Utopian Trantor," the planet that served as the capitol of the galaxy (Nicholls 623). The paradise of order, stability and prosperity was lost throughout the galaxy. The Empire had fallen. While Asimov's plot was primarily based on the fall of the Roman Empire, it also parallels the loss of the Garden of Eden. However, Asimov not only saw man as fallen but risen as well. Whereas man was and still is fallen in the eyes of anyone above, Asimov still felt that man had risen very high in relation to the animals. He took pride in such achievements as the use of fire, expansion of the mind and creation of civilizations. Asimov once justified his idea the separation of humanity from all other animals by man's concept of time: "An animal may remember, but surely it can have no notion of 'past' and certainly no of 'future'." He did admit, though, that this view reminds man that he is fallen. "No non-human creature can foresee the inevitability of it's own death. Only man is mortal, in the sense that only man is aware that he is mortal" (Asimov, Time and Space iv). Quite possibly Asimov's most innovative and influential contribution to modern mainstream science fiction was the idea of psychohistory. Psychohistory is a "purely imaginary though attractive science...based on the notion that the behavior of humans in the mass could be predicted." (Nicholls-480). However " ' a further necessary assumption is that the human conglomerate be itself unaware of psychohistoric analysis in order that its reactions be truly random...'" (480-481). Asimov himself described the science as something that "dealt not with the man, but with man-masses. It was the science of mobs; mobs in their billions." He bragged that millennia from now, the science could predict populus reactions with the accuracy current physics can predict the vector trajectory of a billiard ball based on the angle from which it is struck. The more detailed the information and data is collected, then the accuracy grows greater. However, he added that the "reaction of one man could be forecast by no known mathematics" and under the right circumstances one individual had the power to throw all predictions into the wind (Asimov, Foundation and Empire vii). Whereas the Foundation novels introduced and illustrated the positive uses of psychohistory for the benefit and welfare of humanity, the Space Trilogy conclusion, That Hideous Strength, outlined the disadvantages, should science be perverted and abused by those with no morals. The manipulations of N.I.C.E. of the media concerning the events in Edgestow were a classic example of a primitive form of psychohistory being abused not for scientific observation, but N.I.C.E.'s own unscientific goals. This abuse is first made evident during a conversation between Mark Studdock and Feverstone when Feverstone states: "Once the thing gets going we shan't have to bother about the great heart of the British public. We'll make the great heart what we want it to be'" (43). When the murder of William Hingest was announced, a very positive spin was put on the quick response time by the N.I.C.E. police force (81). In two cases, Studdock was asked to write a report on something before he'd even seen it. One case was an evaluation of Cure Hardy, before he got to travel there (85) and the second case was a report on a planned riot that hadn't even taken place yet (129). The reports of the riot demonstrated N.I.C.E.'s principal tactic of controlling both sides of the media; as Miss Hardcastle revealed it is "absolutely essential to keep a fierce Left and a fierce Right, both on their toes and terrified of each other" since "That's how we get things done" (99). Knowing the stimulus-response relationship between what the public read and heard and how they reacted to it allowed N.I.C.E. to utilize a primitive form of psychohistory toward its negative intentions. While Freudianism isn't psychohistory, maybe not even too closely related, the two sciences use psychological data to predict and manipulate behaviour. Lewis's use of pre-psychohistory with N.I.C.E. implies an evil about the science and made an effective argument against it. Bruce R. Reichenbach believed that Lewis objected to any theories of such a nature because the theories "claim to refute the existence of objective values on the ground they can be explained in terms of subjective factors" (105). Simply put, something like psyhohistory would imply that one could take God out of man. Like their differences on the subject of psychohistory, man's relationship with machine was another gulf between Lewis and Asimov. Asimov's published opinions on the advantages of machinery focus primarily, as did much of his fiction, on robotics. He stated that robots can be useful in replacing humans in hazardous situations such as "in space, in mines, underwater, in explosives factories, in places where one must deal with radioactive substances or new chemicals with uncertain effects." Robots could serve in other hazardous duty areas with known dangerous chemicals or pathogenic bacteria or places humans cannot or should not go due to temperature, heights or pressures (Asimov, Robots 202). Asimov foresaw only two challenges to the expansion and sophistication of robotical assistance. One was the technological challenges of research and development, design and experimentation. The second was the attitude of the everyday public citizens (201). Lewis, on the other hand, seemed more pessimistic about the rapid acceleration of technological progress. If Out of the Silent Planet was any indication, he rejected any notion of dependence on technology whatsoever. Judith L Fisher stated: "He rejects science and replaces it with communication. Technology on Malacandra is directed toward aesthetic ends and each species' work is also their play" (Lowenberg 178). Lewis was once quoted as stating that technology couldn't deliver what it promised: "Their labor-saving devices multiply drudgery; their aphrodisiacs make them impotent; their amusements bore them; their rapid production of food leaves half of them starving." (Reichenbach 103). Born not too many years apart, Lewis and Asimov witness very similar times and events, sometimes the very same progressions in technology. Both served in a World War, where Lewis saw airplanes and tanks introduced to the world in the first, and Asimov served in the conflict that unleashed the fury of a single atom on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While technological innovation seems to be spurred by war, and more specifically defense budgets, many productive civilian uses come about of it. Jet engines, space exploration, plastics and other synthetic materials were all a result of the second great war alone. The following pages are a comparison of Lewis's and Asimov's usually differing opinions on modern science and technology. Between Lewis and Asimov, Asimov is the believer in the advantages of science and technology. His observations and beliefs concerning robotics have already been noted. Aside from robots, his defining moment of transition from lower technology to accepting higher technology was his day of using a word processor instead of his typewriter. He immediately found his word processor to be more helpful as the keyboard was lighter on his fingers and was actually able to improve on his 90 word a minute pace (though he never timed himself again for fear of inflating his ego). He also found revision and proof reading to be easier, since a few mistakes tend to creep in here and there when writing at such a furious pace (Asimov, Roving Mind 338). Asimov lived long enough to witness home computers, cellular phones, beepers, CD's and the Internet; and, as mentioned, just the simple change from a typewriter to a word processor improved his life and career forever for the simple joy it gave him. Alternatively opposite Asimov, Lewis was willing to point out the disadvantages of a scientifically and technologically advanced world. "Lewis seems to prophesy the present: a society drowning in its own waste and governments willing to tolerate environmental carnage to exploit earth's natural resources to protect corporate profits." Reichenbach went on to list the evidence to support Lewis. Land cannot be condemned quickly enough to match the amount of solid waste needing landfills. Liquid waste is buried or put to sea, where it will contaminate and pollute drinking water even longer than if it were dumped directly into the nearby streams. Radioactive waste of nuclear power plants, hospitals and university laboratories are produced faster than sites for waste disposal are found (108). Lewis's fears of an iron and pavement world was expressed in N.I.C.E.'s admiration of the moon which had "purity" and "not one blade of grass, not one fibre of lichen, not one grain of dust" (Lewis, Hideous Strength 175). Lewis and Asimov both realized that the size of technology had created problems, but both offered different solutions. Asimov proposed more technology; Lewis, so disgusted by the pillage of the planet, suggested that nothing less than divine intervention. For the energy problem, Asimov suggested nuclear fusion and solar energy (Asimov, Roving Mind 86). As for industry, he suggested transferring it all to the moon, with its quarter of a million mile distance providing a zone of comfort for earth, and the asteroids could yield enormous amounts of raw material running short back home (87). Lewis admitted that "from Science herself the cure might come" but felt that any taming of the technological monster enveloping the world would probably require the aid of something greater than man. God would be a safe guess (Reichenbach 111). The issue of creationism may actually be the narrowest gulf between Lewis's and Asimov's opinions. "For Lewis, evolution is a genuine scientific hypothesis; it is a biological theorem about the changes undergone by organisms." However, Lewis was wary of evolution being treated as a philosophy rather than a theory. He complained about how modern science used "evolution...to explain away one's belief in objective values and in God" (Reichenbach 104). Asimov also called evolution a theory, but put more faith in it as a "detailed description of some facet of the universe's workings that is based on long-continued observation" and as a scientist himself (Asimov, Roving Mind 7). However strongly he believed in the accuracy of the theory, he, like Lewis, was wary of "blind faith" and "dogmatism" in modern science (8). One of Lewis's main concerns about modern science was its way of robbing the world of its soul. Lewis once noted that science "by reducing nature to her mathematical elements substituted a mechanical for a genial or animistic concept of the universe." Basically, Lewis was implying that science was deflating aesthetic beauty to mere numbers. "The world was emptied, first of her indwelling spirits, then of her occult sympathies and antipathies, finally of her colours, smells and tastes" (Reichenbach 100). On the issue of science killing beauty, Asimov was perhaps at his most vehement, particularly in astronomy. He saw more than the 2500 stars visible on the best nights. It staggered his imagination that there were possibly up to 300,000,000,000 burning suns in this galaxy alone and maybe another hundred billion galaxies out there. He shuddered to watch the hurricanes of Jupiter with such size and violence "that could gulp down the whole earth." He loved images of dead cratered worlds, worlds with volcanoes grander than Mt.Everest churning debris into the endless night and pink deserts of nothing "-each with a weird and unearthly beauty that boils down to a mere speck of light if we just gaze at the night sky." With all the death in the heavens and the only known life on earth, the more Asimov studied astronomy, the more he valued the beauty of earth (Asimov, Roving Mind 114). In the book Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, one can see that while Lewis may not have written much pure science fiction, he definitely studied the genre thoroughly. In the essay "On Science Fiction", Lewis defined what he considered the five main subspecies of the genre to be. The first he discussed is the one he described in a poem, dealt with in the next paragraph. The second he called the "fiction of the Displaced Persons" (62). It dealt with imagination applied to the future of science and he said he was too scientifically illiterate to criticize it. The third subspecies Lewis described as "scientific but speculative" (63). This area attempted to imagine what new settings never actually traveled to would be like. Lewis recognized that the field was original and said it should be judged by its own rules, but warned against redundancy in an area built upon fresh ideas. He classified the fourth as eschatological dealing not with general future events, but specifically the "ultimate destiny of our species" (66). Lewis found these stories offering fresh insight or points of view on many issues. The last subspecies he defined simply represented "an imaginative impulse as old as the human race working under the special conditions of our own time" (67). He classified the Ransom trilogy as being a member of this branch. Probably the quintessential epitome of Lewis's statements about science fiction in the first subspecies was his poem "An Expostulation / Against too many writers of science fiction". It stated very clearly his opinions concerning the purpose and usefulness of the genre. He complained about "empires that cover galaxies" especially if "we find / the same old stuff we left behind" such as "stories of / Crooks, spies, conspirators or love" when these should have been left in "this green floored cell / Roofed with blue air, in which we dwell". Lewis felt that science fiction should be reserved for those stories going where "the Unearthly waits" and readers can find "strangeness that moves us more than fear". Lewis was basically stating that traditional, intrahuman stories should be left where they have always beenon earth (Poems 58). It is unclear if Asimov ever knew about Lewis's anti-Empire jab, or if he took it personally, because Asimov is credited with individually solidifying and introducing the galactic empire concept into modern mainstream science fiction (Nicholls 238). Asimov, again to Lewis's probable disliking, uses old stories in new settings but with a twist: Donald A. Wolheim recognized Asimov as more than recycling reused plots. Asimov illustrated that certain lessons of history will repeat in the future if humanity does not learn any better. The historical patterns, "though similar, differ in scope, differ in intensity and in internal nature," happen through the rise of civilizations, so "certain events seem to recur predictably but always on a new and vaster level." Wolheim credited Asimov with enabling authors to "analyze present day stories and place them into that framework of millions of years to come." (Riley 8). Though C.S. Lewis and Isaac Asimov lived through many of the same events and years, were both highly educated and lived in countries they weren't native to, they had very differing opinions on almost all subjects from the style of their writing to modern technology. This probably arose from one being a Christian apologist and the other a chemist. They did seem to agree on evolution as a theory and warning against dogmatism in science, but that was about it. They both saw the power in sciences like psychohistory, but had differing outlooks on its use. Studying Lewis seems to imply that for him the way of the future was faith. For Asimov, it was technology. Since psychohistory won't be fully developed for a few hundred millennia, it is the assumption of this little known author that only time will tell which one of the great two were right (but he has a feeling it'll be Lewis). Works Cited Asimov, Isaac. Foundation and Empire. Garden City, NY: Double Day & Company, 1952. --- Of Time and Space and Other Things. Garden City, NY: Double Day & Company, 1952. --- Robots: Machines in Man's Image. NY: Harmony Books, 1985. --- The Roving Mind. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1983. --- Second Foundation. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1953. Gunton, Sharon R., ed. Contemporary Literary Criticism. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1981. Hooper, Walter, ed. Of Other Worlds: Essays & Stories. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975. Lewis, C. S. Poems. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1992. --- That Hideous Strength. NY: Scribner Paperback Fiction, 1996. Locher, Frances Carol, ed. "C.S. Lewis." Contemporary Authors. Volumes 81-84. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1979. 328-331. Lowenberg, Susan, ed. C. S. Lewis: A Reference Guide 1972-1988. NY: G. K. Hall & Co., 1993. Nicholls, Peter, ed. The Science Fiction Encyclopedia. Garden City, NY: Dolphin Books, 1979. Reichenbach, Bruce R. "C. S. Lewis on the desolation of de-valued science." Christian Scholar's Review. 11 (Jan 1982): 99-111. Riley, Carolyn, ed. Contemporary Literary Criticism. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1973.