The metalinguistic knowledge of undergraduate students of English

advertisement

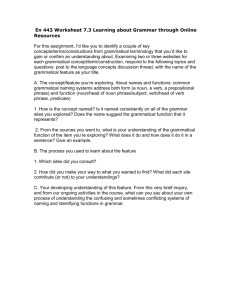

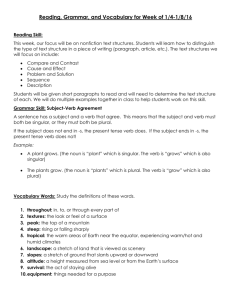

The metalinguistic knowledge of undergraduate students of English Language or Linguistics J. Charles Alderson, Lancaster University and Richard Hudson, University College London Abstract It is often asserted that UK school-leavers know less grammatical terminology than in earlier years. However, objective data on this supposed phenomenon is somewhat scarce. The study reported in this article aimed to see whether and to what extent Knowledge about Language (KaL) has declined over three decades, and how this might relate to university studies and the English school-leaving examinations known as A-Level. We analysed data collected in a test-based survey of UK university undergraduates and compared it with a similar test-based survey conducted in 1986. We also put the studies in context by comparing the performance of UK home students with that of students in and from other countries. In addition, we analysed recent pre- and post-test data on whether courses of instruction in grammar improve undergraduates’ knowledge of grammatical terminology. Our results show a general reduction in school-leavers’ knowledge of grammatical terminology since 1986. Moreover, UK students have a much weaker knowledge than do non-UK students. Studying a foreign language leads to somewhat better levels of knowledge about language, but this is not true for English Language A-level. However, our results confirm that university-level instruction does improve awareness of and ability to use grammatical terminology. We end by discussing the value of Knowledge about Language. 1 Key words: Undergraduate studies of linguistics; knowledge about language; changing levels of metalinguistic knowledge 2 1. Introduction It is a commonplace to remark that incoming UK-based undergraduate students in British universities have a declining knowledge about language (KaL), and in particular that their knowledge of metalinguistic terminology for grammar is very variable. However, objective data on this supposed phenomenon is somewhat scarce. The research reported in this paper contributes to a debate about this hypothesised decline by building on some early work conducted by Bloor (1986a and b), and Alderson, Steel and Clapham (1997). These projects have investigated the knowledge about language (KaL) of university undergraduates in the UK, in one (Alderson et al 1997) relating this to proficiency in French as a Foreign Language. The project which is the object of this paper was funded by the UK Higher Education Academy and had as its aim to see whether and to what extent this KaL has declined over three decades, and how this might relate to university studies and examinations at A-Level. Our study analysed data collected in a survey of UK university undergraduates conducted jointly by the two authors. We also put the studies in context by comparing UK home students with overseas students, both those studying in the UK, and those studying abroad. In addition, we analysed recent data on whether the metalinguistic knowledge of UK undergraduates improves as a result of courses of instruction in grammar. 2. Background 3 One of the main issues in language education, be it the first or a second language, is the role of metalinguistic knowledge, and in particular, knowledge of metalanguage for grammar: is it helpful for students to know about nouns and verbs, or subjects and objects, when developing their skills either in their mother tongue or in a foreign language? During the first two thirds of the twentieth century the pendulum swung strongly in the UK, as in other anglophone countries, against metalanguage and grammatical analysis (Hudson and Walmsley 2005, Kolln and Hancock 2005), but more recently both research-based opinion and official policy have swung back in favour of grammatical KaL. Since 1990, England has had a National Curriculum which puts grammatical KaL clearly onto the school curriculum for both English and Foreign Languages (Anon 1999a, Anon 1999b, Anon 2000, Anon 2003, Anon 2005, Anon 2007). This swing has been supported by research which has shown a direct effect of explicit grammatical instruction, using metalanguage, on the quality of students’ writing (Bryant and others 2004, Hurry and others 2005, Nunes and Bryant 2006, Myhill 2005, Myhill and others 20101, Hancock 2009), on their reading comprehension (Chipere 2001 and on their learning of foreign languages (Ellis 2008). However, this shift in official policy in favour of grammatical KaL has not had any obvious effect on what school-leavers actually know about grammar. As mentioned above, university teachers in language or linguistics departments have not noticed that incoming undergraduates know more grammatical terminology than their counterparts did ten or twenty years ago; and trainee English teachers still worry about how little grammatical KaL they learned either at school or in university (Blake and Shortis 2010, Committee for Linguistics in Education and others 2010), just as they did fifteen years ago (Williamson and Hardman 1995). 4 The aim of this study is to explore the perceived gap between the aspirations of the National Curriculum and the results of KaL teaching in the UK’s schools in the historical perspective of studies that were conducted in 1986, 1992 and 1994, as well as a very limited international perspective. These studies all built on the 1986 one, carried out by Thomas Bloor (at Aston University) in collaboration with one of the present authors (at UCL). Bloor’s 1986 study administered a brief test to undergraduate students who were either entering Modern Languages or Linguistics degree courses at two UK universities (Aston and University College London) or who were second year students in other departments of Aston University taking the Foreign Language option of the Complementary Studies programme. Bloor labelled the former group "linguists" and the latter group he labelled "non-linguists". Each student was given a copy of a test booklet which included the sheet in Appendix 1, which contained the following sentence: Materials are delivered to the factory by a supplier, who usually has no technical knowledge, but who happens to have the right contacts. In this sentence, students were asked to find examples of a number of general grammatical categories which were simply named, without either explanation or examples; so the test revealed whether the students already knew these terms and understood them well enough to find examples. Fifteen test items explored whether students could identify particular parts of speech (verb, noun, adverb, etc.) in a sample sentence. Four additional items tested their ability to identify grammatical functions (subject, predicate and direct and indirect object). Bloor’s findings showed that only verb and noun were correctly identified by all the linguists but some of the non-linguists failed to identify even these parts of speech. Most students failed to meet the Department of Education and Science target (in their 1984 document English from 5 to 16) 5 that 16-year-olds should be able to identify not only verb and noun, but also pronoun, adjective, adverb, article, preposition and conjunction. Over a quarter of linguists failed to identify usually as an adverb...Infinitive was generally handled well by linguists, but not by non-linguists, whereas auxiliary verb fared quite badly with both groups....Well over half the non-linguists were unable to identify the conjunction but, which suggests minimal effective exposure to terminology of this type. (Bloor, 1986b: 159) Bloor concludes that there is a considerable lack of KaL (which he calls language awareness), even amongst this elite group of students studying at university and specialising in languagebased study; by implication we may assume other school-leavers to know even less grammatical terminology Alderson et al (1997) developed a battery of tests, including the 19 items from the Bloor test, and administered it to first-year students of French at seven UK universities. In addition, Lancaster first-year students were retested at the end of their first year, and second- and fourth-year students were also tested, to investigate any change in abilities or knowledge. The main findings were that students' knowledge of metalanguage was highly variable, and there are very few metalinguistic terms which students can confidently be assumed to know even at the end of an undergraduate programme in a language department. 3. This study In 2009, the present authors, with the collaboration of members of the Linguistic Association of Great Britain (LAGB) and the British Association of Applied Linguistics (BAAL), 6 replicated part of Bloor’s study of the knowledge about language of first-year undergraduates at eleven collaborating institutions. This paper presents the results of that study. Research questions 1. Has first-year undergraduate students’ knowledge about language changed from 1986 to 2009? 2. Is there a relationship between the subject of the Advanced-level (A-level) examinations that students have taken in their last two years of school and their KaL? 3. Is there a difference between the KaL of UK-based students and Non-UK students who have not taken UK A-levels? Method A notice inviting participation in the project was posted on the LAGB and BAAL electronic listserves. A total of eleven institutions volunteered to take part. These were Aston University, Birmingham City University, Brighton University, Essex University, Gloucester University, Liverpool Hope University, Middlesex University, Newcastle University, Oxford Brookes University, Reading University, and University College London. The Bloor test of parts of speech and grammatical functions was sent to the volunteers, who administered it in the autumn term of 2009 (see Appendix 1). A total of 726 students took part. In addition, we included for comparison the results of Bloor’s 1986 study (n=238 students) and the 1992 (n=202) and 1994 (n=682) Lancaster studies (Alderson et al, 1997). Results Since the number of students taking part varied greatly by institution and, especially, by ALevel taken, some of the results are expressed as percentages. However, for some analyses we report raw scores as being more meaningful for the particular analysis. 7 RQ 1 Has first year undergraduate students’ KaL changed from 1986 to 2009? Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the five datasets, and Table 2 reports the results of an analysis of variance to establish whether any apparent differences among the datasets are statistically significant. Table 2 shows that the overall difference among groups was not significant (p=.054). However, Duncan’s post hoc tests showed that UK 2009 was always significantly lower than the other four groups, and that there were no other significant differences. Tables 1 and 2 about here In summary, there is no obvious overall downward trend from 1986 to 1994, but the figures for UK students in 2009 are significantly lower than those in 1986, 1992 and 1994. One possible interpretation is that this could be due to the difference between the universities taking part in the earlier Bloor and Alderson et al studies, and those taking part in this survey, which included six post-1992 universities. However, a direct comparison between Bloor’s 1986 Linguists (n=65) and our 2009 Aston + UCL Linguists (n=33) shows a significant decline between 1986 and 2009 (mean scores 1986 = 77.2% and 2009 = 61.6%, t=2.511, p=0.022). Given that the samples of students and universities tested inevitably involved different individuals and to a large extent different universities, the conclusion that there has been a decline in KAL over time can only be suggestive, but certainly the much weaker performance of UK 2009 test-takers is both statistically significant and very marked. Interestingly, it appears that the distribution of scores has also changed. Students in 1986 were more clustered, ie more alike in terms of the level of their KaL, but the students in 2009 8 varied more. This might suggest that universities need to be prepared for much more variation in what they can expect their students to know. RQ 2 Is there a relationship between the subject of the A-level examinations students have taken and their KaL? The A-level examinations taken by the UK students were categorised as English language; Foreign language; both English language and Foreign language; both English language and English literature; Other. However, as only ten students in only one university had taken both English Language and Literature, this A-level is removed from the dataset in what follows. Tables 3 and 4 about here The results of a one-way ANOVA show that there is a significant difference among the means of the four A-level groups. Post-hoc tests show that Foreign Language A-levels, whether alone or in combination with English Language, resulted in significantly higher mean scores. Table 5 about here Table 5 shows the differences between A-level groups by part of speech and grammatical function. In every case, the two groups that had a Foreign Language A-level perform better than the other groups. 9 Surprisingly weak performances are achieved by the English Language A-level. Generally weak performances across the A-level groups are seen in Definite and Indefinite Article, Auxiliary Verb, Finite Verb and Predicate. Figure 1 shows these details in graph, for part of speech only, after ordering the results by mean percentage facility value per item. Figure One about here Figure 1 seems to show a clear disparity between two groups: Group A: English Language + Other, and Group B: Foreign Language with/without English Language. The main differences show up in the middle of the graph, from Preposition to Infinitive, but Group B does not perform much better than Group A in the tail of the graph. That suggests that even Group B does not know more than a handful of terms; for instance, after Definite article, Group B is consistently below 50%. Figure 1 also shows how very close the English Language group are to the Others, even in the fine details of the terms they know best. In summary, the highest scores on the Knowledge about Language test were achieved by the Foreign language A-level group and the English language and Foreign language group. The English language A-level group’s scores were, somewhat surprisingly, considerably lower and non-significantly only marginally higher than the Other A-level group’s scores. An interesting question is what would be an acceptable threshold for considering that a group as a whole “knows” the term. Is it 50%, or should it be higher – perhaps two-thirds of the group should get an item right before we can say that this concept is more known than unknown. 10 RQ 3 Non-UK students compared with UK A-level candidates A total of 64 students in the 2009 cohort were from overseas and had not taken a UK A-level. Their results were compared with the 659 students who had taken UK A-levels. Table 6 presents the percentage scores of the two groups, item by item. The correlation between the two sets of scores was a statistically significant .87, but the difference between the means for the two groups was highly significant (t=5.515, p<.000). Importantly, the Non-UK group had a higher mean score for the 19 items than the UK group (60.28% compared with 42.03%), which suggests that schools in other countries teach grammatical terminology more successfully than in the UK. This difference is all the more noteworthy because non-UK students suffered from taking the test in a language which they may not have used at school. Table 6 about here UK students seem to be notably weaker than Non-UK students in most areas, but most clearly in Passive Verb, Definite and Indefinite Article, Pronoun and Direct and Indirect Object (all of which are in the tail of the graph in Figure 1). Nevertheless, although performing largely better than UK students, Non-UK students do have weaknesses in areas like Auxiliary Verb, Finite Verb, and Predicate. Figure 2 shows these results in graph form, again for parts of speech only, and in rank order of item facility values. Figure 2 about here 11 Figure 2 again shows an increasing divergence in the middle (away from the familiar territory of noun, verb and adjective), with a small convergence on the right (around finite verb and auxiliary verb). If we compare the rankings of the items in Figures 1 and 2, there appear to be three groups: o Group 1, with the first seven items in terms of facility values: Noun, Verb, Adjective, Countable noun, Conjunction, Preposition, Adverb. With the exception of Countable noun (whose meaning is easy to guess), these are the traditional Parts of Speech – toplevel word classes. In Figure 2 the rankings are more or less the same for UK and non-UK. o Group 2, with the next six items: Definite article, Indefinite article, Relative pronoun, Past participle, Passive verb, Infinitive. These are sub-classes of traditional parts of speech, and show somewhat different rankings for UK and non-UK students. o Group 3, with two items: Auxiliary verb, Finite verb. These again are sub-classes, which have the same rank for UK and non-UK. Finite verb is hard for all, perhaps because it is a very abstract category, albeit an important one. The difficulty of Auxiliary verb is, however, unexpected. Once again, these figures raise the question of what the threshold should be above which we can reasonably confidently assume that students have mastered the term and the concept. 4. A replication in Spain 12 A colleague in Spain, Isabel Corona, requested a copy of our partial replication of the Bloor test, and administered it to Spanish students at the University of Zaragoza (a public university ranked in tenth position nationally) in November 2009. The students were about to start taking undergraduate courses in English as a second language and fell into two groups, those entering English degree courses (called "linguists”, n=73) and those entering degree courses in either Engineering or Nursing (called “non-linguists”, n=75). The questionnaire was administered entirely in English. Figure 3 and Table 7 present the results. Figure 3 and Table 7 about here Our correspondent explained that Spain was not affected by the opposition to grammar teaching which occurred in the UK. The notional-functional perspective in second language teaching is known but 'context' and 'function' are barely dealt with in textbooks. Spanish children are introduced to basic notions like subject and predicate at the age of 8 (Year 3 of Primary Education). At eleven or so (Year 6) they apparently already know the elements of the simple clause. Analysis of subordinate clauses and diagramming starts at age 12, at the beginning of Secondary Education. Thus our correspondent asserts that "Spanish school-leavers have undergone formal language teaching for many years, and have been required to reflect on the formal properties of their L1, becoming aware of language properties and rules. They have both implicit and explicit knowledge of the mother tongue and find it 'natural' to transfer this explicit knowledge to the L2 learning process. That would explain, for instance, why many of them have failed to recognise 'finite verb' as such, as this grammatical term is not 13 used in Spanish grammar1. Furthermore, English second language teaching practices tend to follow the three-stage 'PPP' model (presentation, practice, performance), with more emphasis on the first two stages. In Spain, traditional English teaching methodology has focused on making students aware of grammatical rules or problems and then making them practise on them by doing specific exercises. Spanish students of English are able to apply rules in practice exercises after grammar inputs and do it consciously. However, they consistently make errors when confronted with free production, in writing and even more so in spontaneous speech." In the case of Figure 3, the rankings are somewhat different from the UK ones. Compared with UK Group 1 all but Conjunction are at the head of the list. However, compared with UK Group 2, the Spanish students perform much better on Passive verb and Infinitive, and somewhat better on Relative pronoun. As in the UK, Auxiliary verb and Finite verb are the most difficult. However, although the Zaragoza students performed relatively poorly on Finite verb (47.3% of students answered the item correctly), they still performed considerably better than their UK counterparts (only 14.72% of the UK students got the item right). One further difference compared with the UK sample is the much smaller gap between linguists and non-linguists. Although the students taking the test were entering different faculties within the University of Zaragoza, in Spain all secondary schools follow the same 1 Commenting on the figures for "finite verb", she said: "Spanish does not make a specific grammatical distinction between haven't got any term to show that and 'participio' as contrast finite and non-finite forms. So we distinction. We have 'gerundio', ’infinitivo' the terms to refer to non-finite forms, but no term to them with the other 'conjugated' forms (the finite ones in English)." 14 syllabus for a foreign language: there is one compulsory L2 subject and nearly 90% of pupils take English. The national university entrance exam, known as "selectividad", includes a foreign language test that has to be taken by all school-leavers taking the exam, regardless of their speciality. For more details of this study, see Corona and Mur-Dueñas (2010). In answer to RQ3, it would appear that UK students have a much weaker knowledge about language structure than do at least some non-UK students, if we take the non-UK students in our UK sample and all the students in the Spanish sample as representative. This difference is presumably due to different traditions in teaching language and about language, but a great deal more research is needed into other consequences of these teaching differences. 5. Pre- and post-tests Reading University In one case, Reading University, the test results were in effect a pre-test administered at the beginning of the first (Autumn) term to students who would only take a grammar course in the second term of the academic year 2009-2010. This grammar course dealt with a number of topics tested in the partial replication of the Bloor test. The course teacher, Dr Jacqueline Laws, gave students six one-hour lectures on parts of speech and parsing, and they also received two 1-hour seminars, with group sizes between ten and sixteen. The first seminar was on word classes and the second on clause structure, making a total of eight hours of faceto-face tuition in the course. In addition, students were given weekly parsing exercises to do in their own time (it is unknown how many students completed these exercises.) The students 15 who participated were attending a foundation module on 'Sounds, Grammar and Meaning'; 28% of them were studying for a BA in English Language and a further 22% were enrolled on a joint BA programme in English Language and one of the following: English Literature, a Foreign Language or TV Studies. The remaining 50% were studying English Literature, History, Philosophy or Politics. The post-test administered at the end of the course was identical to the pre-test, but no feedback was given to the students on either occasion. The aggregated results of the post-test are given in Table 8 below, together with the results of the pre-test. 64 students did the pre-test, 67 the post-test. However, since the tests were administered anonymously, it is not known whether all 64 were included in the 67. Figure 4 presents the results for the parts of speech in graph form. Table 8 and Figure 4 about here Table 9 presents the descriptive statistics for the nineteen items: Table 9 about here A t-test of the significance of the difference between means showed a highly significant difference (t=5.226, df=18, p=.000), indicating improvement in scores of fifteen percentage points. Unsurprisingly, those concepts that were not covered during the course (“passive verb” and “predicate”) did not improve, whereas those that had been covered did show notable increases, except for noun and verb, which showed a ceiling effect. Interestingly, whilst high scores for “subject” nevertheless increased (from 83% to 99%), similarly high scores for the pre-test of “adjective” showed a marginal decline (86% to 82%) on the posttest. 16 Nevertheless, there were a number of parts of speech and functions that had been taught explicitly but which were still not very well known at the end of the course, including “direct object” and “indirect object”, “infinitive”, “finite verb”, “auxiliary verb” and “past participle” relative pronoun. Lancaster longitudinal project In the academic year 2005-6, the Department of Linguistics and English Language at Lancaster University began a four-year project to monitor the metalinguistic knowledge of incoming undergraduate students of Linguistics and of English Language. The study involved the use of the same test as was used in the studies reported above (plus Sections 2 and 3 of the metalinguistic test used in Alderson et al, 1997, but we do not report on those sections in this paper). Method The test battery was administered as early as possible in the academic year 2005-6, and then repeated towards the end of the same academic year as a form of post-test. It was then repeated in the academic years 2006-7, 2007-8 and 2008-9, the pre-test always taking place before any formal teaching of grammar, in Term 1, and the post-test being administered in the early weeks of Term 3, after students had been exposed to a range of grammatical analyses in different courses. As in the Reading study, students were not given any feedback after the pre-test. Research questions RQ1 Is there any evidence of change in KaL of incoming undergraduates in the period 20052009? 17 RQ2 Is there any improvement in test performance between the beginning and end of the first academic year of study (Time 1 and Time 2 pre-test and post-test)? Evidence of changing KaL The mean pre-test scores on the nineteen test items for the four different cohorts of students are shown in Table 10. A one-way analysis of variance showed that there were no significant differences (F=.816, p=.489) across all four cohorts and a Duncan’s post-hoc test revealed no significantly different contrasts. We therefore assume that there was no significant change in KaL of incoming undergraduates in the period 2005 to 2009. Table 10 about here Results of pre- and post-tests Table 11 shows the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for the pre- and post-tests Table 11 about here Paired sample t-tests for the pre- and post-tests were conducted with the following results (Table 12) Table 12 about here When all years were combined to arrive at a larger n size, the following results were obtained. 18 Table 13 about here The difference between the means of Time 1 and Time 2 was highly significant (-5.012, p<.000), showing that students’ knowledge had increased over the period of one academic year. This is, of course, reassuring, and a report of the mean scores for each item in the test (Table 14) shows that the majority of items were easier at Time 2 than at Time 1, in other words that students had improved. The exceptions were those items that had already been very easy at Time 1 (eg. Verb, Noun, Adjective), which sometimes showed minor declines but were still very easy. A notable increase in performance was seen for Predicate, which had a facility value of 10% at Time 1 but a facility value of 39% at Time 2. However, Table 14 also shows that the improvements were not substantial. Passive Verb, Auxiliary Verb and Predicate were still very low (we would argue unacceptably so) and, after two terms of instruction, figures were frankly surprisingly low also for Adverb, Definite and Indefinite article, Past participle, Finite Verb, Infinitive and Direct and Indirect Object. Table 14 about here We conclude that students’ knowledge about language did increase after taking a course in grammar which confirms the findings of the Reading University study reported above. One possible limitation of this study is that the tests used to measure knowledge about language were not direct achievement tests related to the specific curriculum. Had valid tests of the specific content of the curriculum been available, greater improvement might have been shown. However, different individual students take a wide variety of different courses, and it was felt that a test of parts of speech and grammatical functions could be said to cover the 19 most basic aspects of metalanguage that could be expected to be used across all the various courses. Although the Lancaster study reported here did gather data on students’ ability to use metalanguage to write about linguistic errors and to formulate grammatical rules, that data remains to be analysed in depth. However, a qualitative analysis is under way of the terminology that students use to describe and explain grammatical errors. 6. Overall Conclusion Our results show that there has been a general reduction in school-leavers’ knowledge of grammatical terminology since 1986. Although this downward trend is unclear in the figures for 1992 and 1994, the figures for UK students in 2009 are significantly lower than for 1986, 1992 and 1994 (though, perhaps unsurprisingly, the longitudinal Lancaster study 2005-9 did not reveal any significant change in the period 2005-2009). Moreover, it would appear that UK students have a much weaker knowledge about language structure than do non-UK students; and although studying a foreign language leads to somewhat better levels of knowledge about language, the same cannot be said for studying for English Language A-level. On a more positive note, our results confirm that instruction can and does result in improved recognition of parts of speech and grammatical functions. However, our test only covers rather elementary terminology, and in more difficult terms such as ‘finite verb’ and ‘passive verb’, progress would appear not to be substantial and there is much room for improvement. 20 7. Limitations of the study One obvious limitation of this study is that being able to identify parts of speech and grammatical functions is not all there is to metalinguistic knowledge or KaL. Indeed, Bloor’s original 1986 SPAM (Students’ Prior Awareness of Metalinguistics) questionnaire also had sections on rhetorical terms, aspects of spelling, pronunciation and morphology and an open question which proved very difficult for many students: Give an example of one way in which English differs grammatically from some other language. A second questionnaire dealt with the geographical distribution of languages and language families. It also included questions about prescriptive grammar such as Working class speech is usually careless speech and The original meaning of a word is its true meaning. Bloor himself remarked (1986b: 160): ‘Familiarity with linguistic terminology is no guarantee of accurate observations about language’. In addition, the Lancaster 1992 and 1994 study (Alderson et al, 1997) contained two other sections (one on knowledge of grammatical rules that had been broken in sample sentences, and a test of the ability to identify grammatical functions of words in sentences) which have not been examined in the current paper as they were not included in the other studies reported on here. Even more obviously, explicit declarative knowledge of grammatical terminology is different from implicit procedural knowledge of grammar. The students tested in this project were all competent users of English, including finite verbs, regardless of whether they could recognise and name a finite verb; so we are not, in any sense, suggesting that students’ use of English grammar is defective. There are issues to do with language skills such as writing, and 21 especially so in foreign languages; but this study does not throw any light on these issues (though the quality of metalinguistic knowledge may be relevant to improving language skills). David Crystal (2006), condemning ignorant linguistic prescriptivism, points out that for a substantial period of time in the second half of the 20th century, grammar was abandoned in British secondary schools, but was not replaced with a more descriptive approach to language. He argues (page 205) that grammar is useful if taught properly, though ‘there is much more to language than grammar’ (2006: 206). However, he claims that things have recently changed, and it is worth quoting him at some length describing modern A-level English language classes: Walk into an A-level English language class these days – or, for that matter, lower down the school, into classes where teachers have engaged successfully with the focus on grammar in the National Literacy Strategy – and you would see some fine examples of this approach in practice. You would see students looking critically at the words people use, the sentences in which they use them, the way in which the sentences are put to work in discourse and whether these discourses suit the context in which the speakers or writers are operating. In short, they are learning to judge appropriateness in others…..We can sum it up in another way: students are being taught to recognise and understand the consequences of making linguistic choices (op cit: 210-11). No doubt Crystal is correct. But at the same time, students need a terminology in order to talk about language, and surely the names for parts of speech and grammatical functions are one (arguably small but nonetheless important) part of that terminology. And it appears from this 22 research and previous surveys that there are some serious gaps in students’ understanding and use of linguistic terminology. It would also appear that, although this understanding improves during a course of study, it remains far from satisfactory at the end of the first academic year. It is unclear what the impact of such weaknesses in KaL is on one’s ability to analyse language in general, to talk about language in informed ways, or indeed to learn a new language. Some studies (Alderson and others, 1997, for example) have shown no connection between KaL and proficiency in use of a foreign language by undergraduates. On the other hand, recent work (Myhill and others, 2010) has also shown that explicit discussion of a specific area of grammar does improve native-language writing by school children. We hope that this paper will encourage further research not only on students’ metalanguage, but also on its consequences for learning and cognitive development. References Alderson, J.C., Steel, D. and Clapham, C. (1997) Metalinguistic knowledge, language aptitude and language proficiency. Language Teaching Research. Vol 1, No 2. pp 93121. Anon 1999a. English. The National Curriculum for England. London: Department for Education and Employment; Qualifications and Curriculum Authority Anon 1999b. Not Whether but How. Teaching grammar in English at key stages 3 and 4. London: Qualifications and Curriculum Authority 23 Anon 2000. Grammar for Writing. London: Department for Education and Employment Anon 2003. Framework for teaching modern foreign languages: Years 7, 8 and 9. London: Department for Education and Science Anon 2005. Key Stage 2 Framework for Languages. London: Department for Education and Skills Anon (2007). grammar - where next in english teaching? a response from the secondary national strategy in the context of the "english 21" conversations.Anon. Blake, Julie and Shortis, Tim 2010. Who's prepared to teach school English? The degree level qualifications and preparedness of initial teacher trainees in English. London: Committee for Linguistics in Education Bloor, T. (1986a) University students' knowledge about language. CLIE Working Papers Number 8 Bloor, T. (1986b) What do language students know about grammar? British Journal of Language Teaching, 24 (3) 157-160 Bryant, Peter, Nunes, Terezinha, and Bindman, M 2004. 'The Relations Between Children's Linguistic Awareness and Spelling: The Case of the Apostrophe.', Reading and Writing 12: 253-276. Chipere, Ngoni 2001. 'Variations in native speaker competence: Implications for native language teaching', Language Awareness 10: 107-124. 24 Committee for Linguistics in Education, Blake, Julie, and Shortis, Tim 2010. 'The readiness is all. The degree level qualifications and preparedness of initial teacher trainees in English', English in Education 44: 1-21. Corona, Isabel. and Mur-Dueñas, Pilar (2010). 'Getting to grips with grammar: native vs non-native first-year undergraduates. A contrastive application of the KAL test'. 28th International Conference of the Spanish Society for Applied Linguistics, AESLA 2010, "Analysing Data, Describing Variation". ISBN: 978-84-8158-479-0. Crystal, David. (2006). The Fight for English: How Language Pundits Ate, Shot and Left. Oxford: Oxford University Press Department of Education and Science (1984) English from 5 to 16. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office Ellis, R. 2008. 'Explicit form-focused instruction and second language acquisition.', in Bernard Spolsky & Francis Hult (eds.) The Handbook of Educational Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell, pp.437-455. Hancock, Craig 2009. 'How linguistics can inform the teaching of writing', in Roger Beard, Debra Myhill, Jeni Riley, & Martin Nystrand (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Writing. London etc: Sage, pp.194-207. Hudson, Richard and Walmsley, John 2005. 'The English Patient: English grammar and teaching in the twentieth century', Journal of Linguistics 41: 593-622. 25 Hurry, Jane, Nunes, Terezinha, Bryant, Peter, Pretzlik, Ursula, Parker, Mary, Curno, Tamsin, and Midgely, Lucinda 2005. 'Transforming research on morphology into teacher practice', Research Papers in Education 20: 187-206. Kolln, Martha and Hancock, Craig 2005. 'The story of English grammar in United States schools', English Teaching: Practice and Critique 4: 11-31. Myhill, Debra 2005. 'Ways of Knowing: Writing with Grammar in Mind', English Teaching: Practice and Critique 4: 77-96. Myhill, Debra, Lines, Helen, and Watson, Annabel (2010). Making meaning with grammar: a repertoire of possibilities. Unpublished. Nunes, Terezinha and Bryant, Peter 2006. Improving Literacy by Teaching Morphemes. London: Routledge Williamson, John and Hardman, Frank 1995. 'Time for refilling the bath? A study of primary student-teachers' grammatical knowledge.', Language and Education 9: 117-134. 26 Table 1 Comparison of data from 1986 - 2009 Minimum Maximum % % co cor Std. rre rec Mean ct t % correct BLOOR 1986 Lancaster 1992 Lancaster 1994 UK 2009 Non-UK 2009 9.24 4.46 2.20 7.13 21.88 97.06 97.52 98.53 92.87 93.75 58.14 59.96 63.87 42.03 60.28 Deviat ion 22.240 24.259 24.088 27.846 19.739 27 Table 2 One-Way ANOVA of five datasets and results of Duncan's posthoc tests: Means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed Sum of Square s df Between Groups 5490.947 Within Groups 49742.063 Total 55233.010 4 88 92 Mean Square F Sig. 1372.737 565.251 .054 2.429 Subset for alpha = 0.05 Duncan Group UK 2009 Bloor All Lancaster 1992 Non-UK 2009 Lancaster 1994 Sig. N 659 238 202 64 682 1 42.0254 1.000 2 58.1380 59.9560 60.2796 63.8726 .510 28 Table 3 Descriptive statistics for the four A-level groups Std. English Language Foreign Language English Language and Foreign Language Other Valid N (listwise) Deviat ion N Minimum Maximum Mean 331 46 78 8.50 15.22 5.79 92.16 100.00 94.78 40.4197 29.41924 59.1533 25.22300 57.7277 24.81357 197 652 3.18 91.44 37.4354 28.51607 29 Table 4 One way Analysis of Variance across A-level groups and and results of Duncan's post-hoc tests Sum of Square s df Between Groups 7338.267 Within Groups 52750.274 Total 60088.541 3 72 75 Mean Square F Sig. 2446.089 732.643 .024 3.339 Subset for alpha = 0.05 Duncan Group Other English Language English and Foreign Language Foreign Language Sig. 1 2 3 37.4354 40.4197 40.4197 57.7277 57.7277 .735 .053 59.1533 .871 30 Table 5 Differences between A-level groups by part of speech and grammatical function Part of speech/ English Foreign English Other grammatic langua language lan % correct al function ge % correct gu % correct ag e an d Fo rei gn lan gu ag e % correct Verb 91.18 97.83 94.63 89.86 Noun 92.16 100.00 94.63 91.44 Countable noun 54.90 69.57 64.56 47.11 Passive verb 14.38 34.78 46.43 13.35 Adjective 74.51 91.30 82.34 73.61 Adverb 40.52 76.09 54.79 38.27 Definite article 30.07 47.83 46.02 23.13 Indefinite article 26.47 39.13 45.41 17.66 Preposition 33.33 54.35 66.99 25.85 Relative pronoun 22.22 39.13 51.81 31.80 Auxiliary verb 13.40 32.61 37.37 10.37 Past participle 19.28 56.52 60.74 23.50 Conjunction 72.22 73.91 75.84 56.87 Finite verb 10.13 34.78 23.26 18.81 Infinitive 11.76 71.74 62.63 11.85 Subject 90.20 95.65 94.78 86.31 Predicate 8.50 15.22 5.79 3.18 Direct object 29.74 52.17 64.05 26.06 Indirect object 33.01 41.30 24.75 22.25 31 Table 6 Comparison of item scores of UK and Non-UK students Part of speech/ grammatical UK % correct Non-UK % correct function N=659 N=64 Verb 91.20 85.94 Noun 92.87 93.75 Countable noun 55.24 82.81 Passive verb 18.51 54.69 Adjective 76.18 81.25 Adverb 42.94 53.13 Definite article 29.89 64.06 Indefinite article 26.40 62.50 Preposition 34.45 67.19 Relative pronoun 26.86 56.25 Auxiliary verb 15.02 37.50 Past participle 27.01 46.88 Conjunction 68.29 59.38 Finite verb 14.72 28.13 Infinitive 21.70 48.44 32 Subject 88.01 87.50 Predicate 7.13 21.88 Direct object 32.47 59.38 Indirect object 29.59 54.69 33 Table 7 Results of Linguists and Non-Linguists at the University of Zaragoza, Spain Linguists Non-linguists TOTAL 73 75 148 % % % Verb 72 98.6 73 97.3 145 98 Noun 72 98.6 75 100 147 99.3 Countable noun 72 98.6 66 88 138 93.2 Passive verb 68 93.2 70 93.3 138 93.2 Adjective 73 100 67 89.3 140 94.6 Adverb 62 84.9 60 80 122 82.4 Definite article 65 89 53 70.7 118 79.7 Indefinite article 65 89 51 68 116 78.4 Preposition 64 87.7 69 92 133 89.9 Relative pronoun 69 94.5 61 81.3 130 87.8 Auxiliary verb 57 78.1 42 56 99 66.9 Past participle 57 78.1 49 65.3 106 71.6 Conjunction 52 71.2 49 65.3 101 68.2 34 Finite verb 35 47.9 35 46.7 70 47.3 Infinitive 67 91.8 69 92 136 91.9 Subject 68 93.2 70 93.3 138 93.2 Predicate 69 94.5 65 86.7 134 90.5 Direct object 64 87.7 56 74.7 120 81.1 Indirect object 59 80.8 62 82.7 121 81.8 Functions 35 Table 8 Reading University Pre- and Post-test results (% correct) Item Pre-test Total Pre-test % Post-test Total Post-test % n = 64 n = 67 Verb 61 95 66 99 Noun 62 97 67 100 Countable noun 36 56 49 73 Passive verb* 12 19 14 21 Adjective 55 86 55 82 Adverb 33 52 44 66 Definite article 26 41 32 48 Indefinite article 20 31 28 42 Preposition 23 36 47 70 Relative pronoun 13 20 38 57 Auxiliary verb 14 22 24 36 Past participle 17 27 35 52 Conjunction 47 73 54 81 Finite verb 7 11 25 37 36 Infinitive 17 27 26 39 Subject 53 83 66 99 Predicate* 2 3 0 0 Direct object 18 28 34 51 Indirect object 16 25 38 57 * these concepts / terms were not covered in the course 37 Table 9 Descriptive statistics for pre-and post test, percentage scores Mean N Std. Std. Error Deviation Mean Pre test % 43.79 19 29.472 6.761 Post test % 58.42 19 27.001 6.194 38 Table 10 Means and standard deviations for the four cohorts of incoming undergraduates of Linguistics and English Language Year Means (k=19) Mean as percentage of number of items 2005-6 (n=40) 10.83 (4.175) 57% 2006-7 (n=21) 10.33 (3.6380 54% 2007-8 (n=54) 9.74 (2.909) 51% 2008-9 (n= 23) 12.22 (3.630) 64% 39 Table 11 Descriptive statistics of the pre and post tests (Time 1 above, Time 2 below). Year Section 1 (k=19) Mean as percentage of number of items 2005-6 (n=40) 2006-7 (n=21) 2007-8 (n=54) 2008-9 (n= 23) 10.83 (4.175) 57% 12.88 (2.839) 68% 10.33 (3.6380 54% 14.29 (3.165) 75% 9.74 (2.909) 51% 11.94 (4.114) 63% 12.22 (3.630) 64% 13. 48 (3.930) 71% 40 Table 12 Significance of the difference between Time 1 and Time 2 shown in Table 11 Year Section 1 2005-6 (n=40) p=.001 2006-7 (n=21) p<.000 2007-8 (n=54) p<.000 2008-9 (n=23) NS 41 Table 13 Significance of the difference between Time 1 and Time 2 – All years combined N size Section 1 (k=19) Mean as percentage of number of items 138 10.56 (3.611) 56% 12.83 (3.673) 68% 42 Table 14 Item analyses by Year and Times 1 and 2 (figures = % correct) Item Years 2005-9 N = 138 Time 1 Time 2 Verb 95 93 Noun 95 93 Countable noun 71 90 Passive verb 17 16 Adjective 89 91 Adverb 51 67 Definite article 54 77 Indefinite article 47 69 Preposition 55 82 Relative pronoun 59 79 Auxiliary verb 25 34 Past participle 54 62 43 Conjunction 78 86 Finite verb 28 54 Infinitive 37 46 Subject 96 99 Predicate 08 31 Direct object 57 77 Indirect object 40 40 44 No un Ve Ad rb je Co ctiv e n j Co u un nct io ta n bl e no un Ad v Pr er e b Pa p os it i st pa on r ti cip le I De nfin iti fin Re ite ve ar la t ic tiv le e In pr de on f in o ite un Pa arti cl ss iv e Au e v er xil b ia ry ve Fi rb ni te ve rb 120 100 80 English language Foreign language 60 40 English language and Foreign language Other 20 0 Figure 1 Facility values of parts of speech items, by A-Level 45 100 90 80 70 60 50 UK Non-UK 40 30 20 10 0 b iv e b b un erb tive o un tio n tion e rb icle icle oun ip le er e r ver it t t v v v i n c r V c r n n c No s i d a a je ro A r ti ve Inf iar y nite un p o le ite nite e p pa ssi Ad tab o nj re n Fi xil t i v i a i P f C P ef e un at Pas Au l d o D C In Re Figure 2 Facility values of parts of speech items, by UK and non-UK 46 120 100 80 linguists 60 non-ling 40 20 0 un no n e n n n rb ive rb rb rb erb le le le t o u ve nitiv itio n ou d ve rtic rtic icip ctio ve v ve s i e c e n ve o t y j a a f n a r r ite u pr a a in epo j e e n i ad abl ssi t t i l n i i f t p co t xi in in pr tive pa e f de f pa s un au a l d o c re in Figure 3: Facility values of parts of speech items, by Linmguists and non-Linguists in Zaragoza 47 120 100 80 pre 60 post 40 20 0 un no e n rb un io t iv ve no ct ec j n le u ad nj ab co unt co * b e n rb rb oun le le le rb er itiv ve ve rtic sitio rtic icip n ve e v n d i o t y a a f a t o r pr in iliar ive fini ep nite t p a it e x i ve a ss in pr f i f s u t a p la de de pa in re Figure 4: Facility values of parts of speech items, by pre- and post-test, Reading University 48 Appendix 1 The Test of Metalinguistic Knowledge Library card number: _______________________ ENGLISH GRAMMAR ABOUT YOU Did you take English Language at ‘A’Level? Y / N If your answer is ‘Y’, which board did you take the exam with? __________________________ Which courses are you taking in Part I within the Department of Linguistics? Tick those that apply LING 101 LING 132 LING 152 LING 130 LING 133 LING 153 LING 131 LING 151 SECTION ONE: GRAMMATICAL CATEGORIES AND FUNCTIONS (5 minutes) You are advised to take no more than 5 minutes on this section. 1. From the sentence below select one example of the grammatical item requested and write it in the space provided. NOTE: You may select the same word (s) more than once if appropriate: Materials are delivered to the factory by a supplier, who usually has no technical knowledge, but who happens to have the right contacts 49 1. verb ...........……………………………………………………………………….. 2. noun ............……………………………………………………………………… 3. countable noun ..............………………………………………………………….. 4. passive verb ...............…………………………………………………………… 5. adjective ................……………………………………………………………… 6. adverb ..............………………………………………………………………….. 7. definite article ........………………………………………………………………. 8. indefinite article.........……………………………………………………………… 9. preposition ..........………………………………………………………………… 10. relative pronoun ........……………………………………………………………. 11. auxiliary verb .........……………………………………………………………… 12. past participle .......……………………………………………………………… 13. conjunction ........……………………………………………………………… 14. finite verb ...............……………………………………………………………… 15. infinitive verb .........…………………………………………………………….. 2. In the following sentences, underline the item requested in brackets: 1. Poor little Joe stood out in the snow (SUBJECT) 2. Joe had nowhere to shelter (PREDICATE) 3. The policeman chased Joe down the street (DIRECT OBJECT) 50 4. The woman gave him some money (INDIRECT OBJECT) 51