promises kept - Florida Developmental Disabilities Council

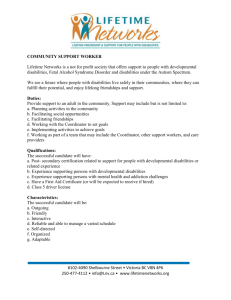

advertisement