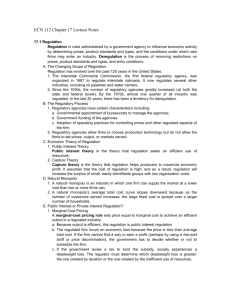

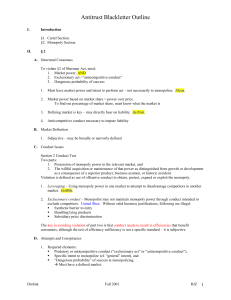

Trade Regulation (5th Ed., Pitofsky, Goldshmid, Wood)

advertisement