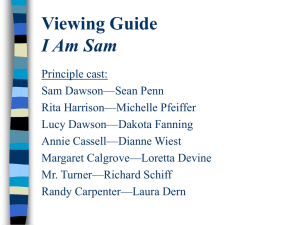

GOSS MOH IMSAM guidelines_Nov15 word 2009 version

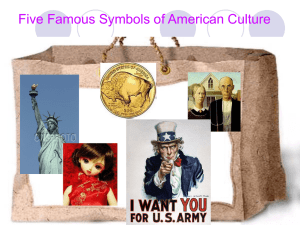

advertisement