Neithercut Woodland Management Plan: Small Mammals

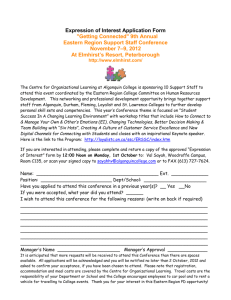

advertisement

Neithercut Management Plan Rob Herman Mandy Oberholzer Don Brown December 2, 2009 Central Michigan University Wildlife Biology and Management BIO 541 Fall 2009 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Species Background…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Management Goals and Objectives………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 Area Description……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 Past and Present Land Conditions……………………………………………………………………………………………………......................16 Management Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..17 Evaluation Techniques and Monitoring Plan……………………………………………………………………………………………………......20 Criteria for Identifying Success……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...23 Timeline………………………………………………………………………………………..................................................................................23 Budget……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….24 References……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………26 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………….................................................................................29 Tables and Figures Figure 1. North American Porcupine…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Figure 2. North American Porcupine…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Figure 3. Distribution of North American Porcupines……………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Figure 4. Eastern Cottontail Rabbit…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Figure 5. Eastern Cottontail Rabbit…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Figure 6. Distribution of Sylvilagus floridanus……………………………………………………………………………………………………....9 Figure 7. Eastern Gray Squirrel……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Figure 8. Eastern Gray Squirrel (black color phase)………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Figure 9. Native Distribution map of Scirus Carolinensis…………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Figure 10. Map of Neithercut woodland…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 Figure 11. Photograph of Josiah Littlefield…………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Figure 12. Soil types of Neithercut woodland………………………………………………………………………………………………………14 Figure 13. Landuse/cover types of Neithercut woodland…………………………………………………………………………………………...15 Figure 14. Land Cover of Neithercut woodland…………………………………………………………………………………………………….16 Figure 15. Proposed thinning areas in Neithercut woodland………………………………………………………………………………………..18 Figure 16. Brushpile construction steps…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….19 Figure 17. Mowing/disking strategies………………………………………………………………………………………………………………20 Figure 18. Hair Collection Tube…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….21 Figure 19. Timber Sale Bid Report………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….25 Table 1. Budget…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………......27 2 Abstract This management plan is intended to benefit three small mammals, the North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum), Eastern cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus), and the Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). The plan involves some minor and major habitat alterations to help improve the quality of the habitat for these species. This plan will be accomplished by utilizing management techniques such as: prescribed burns, timber harvests, mowing/disking of grasslands, and brush pile constructions. This plan will be monitored with the help of volunteers as well as some hired workers that will carry out different monitoring techniques such as: trapping, locating and counting den sites, as well as live counts. The estimated costs for this management plan is about $9,000 dollars, but will net (profit) of approximately $41,000 dollars. Introduction North American Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) Life History The North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) is the second largest rodent on our continent, behind only the beaver. Porcupines are a very unique animal, and taxonomically it is the only species in its genus. They are a solid dark brown color, and their quills are dark brown as well. The quills on the porcupine’s back may have some yellow mixed in with the brown, and the tips of the quills are usually white. Porcupines can weigh anywhere between 10-30 pounds, and they can be 2-3 feet long. The quills are about 7.5 cm long on a fully-grown porcupine, and there are about 30,000 total quills (Weber, C. and P. Myers. 2004). Every quill has a microscopic barb on the end of it, so body heat and movement help to work the quill in deeper into the flesh. This can cause a nasty infection and possible death. Animals that take quills in the face can starve to death because it is too painful to try and eat. 3 Porcupines are very good climbers, and they prefer to be up in trees because the majority of their predators are ground dwelling. They are suited very nicely for climbing, because they have 4 claws with a thumb on their fore-legs, and 5 claws on their hind-legs. Also, they have very leathery palms which further aids in climbing. The main natural predators to porcupines are fishers and mountain lions. Fishers repeatedly attack the face until the porcupine is wounded enough to be flipped on its back and attacked on the soft ventral side. Other animals that have been known to prey on porcupines are lynx, bobcats, great horned owls, wolves, coyotes, and wolverines. Figures 1 & 2: North American Porcupines. Porcupines are sexually dimorphic with the males being larger than the females (Sweitzer and Berger, 1997). Breeding takes place once a year during the fall. Males compete for a female, and the largest male is usually selected by the female. Males can have more than one female mate, and therefore polygamy is exercised. The gestation period lasts around 200 days, so the baby is born in the late spring. There is usually only one baby born at a time, but sometimes there are two. The baby is weaned for about 4 months, and after 5 months the baby becomes independent. Sexual maturity doesn’t occur in females until 25 months, and 29 months for males (Weber, C. and P. Myers. 2004). Porcupines spend a majority of their day foraging for food, and they can eat up to 10% of their body weight in a day (about a pound). Their diet is strictly herbivorous, and they like to eat the bark, cambium, and needles from many trees. Porcupines love to eat beech saplings, aspen, and hemlock trees, but they also like the buds of sugar maples before the leaves begin to sprout. Beech nuts and acorns are also gathered when they are still in the trees so the porcupine does not have to compete with squirrels and deer when they are on the ground. In the spring they may expand their diet to berries, nuts, plant buds, and twigs. They do most of their eating at night to 4 take advantage of the higher nutrients in the plants during respiration (Roze 1989). Hemlock trees are the most useful tree to the porcupine, because they are high in nutrition, provide good cover for predator protection, retain body heat well, and are strong (Weber, C. and P. Myers. 2004). However, porcupines do not feed in the same trees that they rest in. Porcupines have a strong attraction to salt, which can make them a pest because they have been known to chew on housing structures, vehicles, and are often killed by cars eating the salt on roads in the winter. Porcupines can be a nuisance to the timber industry, because they can disfigure and stunt the growth of possible lumber trees. However, their overall affect on the timber industry is quite insignificant. Porcupines are not very social creatures, and each porcupine has its own home territory. Dominant males have a home range of about 20.7 hectares, and subordinate males have a home range around 12.9 hectares. Females have a home range of about 8.2 hectares, and males may overlap 3-10 female ranges during breeding season (Sweitzer, 2003). Porcupine population densities in viable habitats range from 1-9.5 individuals/km2. They have cyclical population peaks every 12-20 years (Woods 1973). The Neithercut Woodland is a prime habitat for porcupines, not only because the vegetation is appropriate, but also because it is large enough to support 1-9.5 porcupines. It is a forest of 242 acres, and that converts to just about 1.02 km2. Porcupines sometimes den together in the winter, but there is no correlation between porcupines that mate together will also live together. Porcupines make their dens in hollow logs or trees, small caves, rock piles, or brush piles. They are active all year round, are nocturnal, and they do not hibernate (Weber, C. and P. Myers. 2004). When porcupines feel threatened they try to do everything they can to avoid using their quills. Initially, they will make a chattering noise will their teeth to alert the nuisance that they want to be left alone. If this doesn’t work they will emit a foul odor, and lastly they will use their quills if need be. Porcupines generally have a lifespan of about 6 years in the wild (Kurta, 1995; Roze, 1989). Habitat Porcupines can live in a wide variety of habitats. They are commonly found in tundra, deserts, and deciduous forests at varied climates and elevations. They are capable of living both 5 on ground and up in trees. Time spent on land tends to correlate with amount of trees in the area. Porcupines of the forest tend to spend the majority of the time in trees, while porcupines of the southern deserts spend all day on land. Rock dens are generally their first choice during winter, but they are just as capable as using trees for dens. North American porcupines are listed as animals of least concern (Weber, C. and P. Myers. 2004). Range The North American porcupine’s range consists of the Yukon Territory down throughout the southern Canadian provinces, then south along the West and Midwest U.S. into northern Mexico. It is also found in the New England states, but is less common moving south along the eastern coast. The porcupine can be found in desert areas, but its desired habitat is a mixed conifer/hardwood forest. Figure 3: Distribution of N.A Porcupines. Eastern Cottontail Rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus) Life History The cottontail’s genus name, Sylvilagus, connects the Latin word silva, meaning “forest”, and the Greek word lagos, meaning “hare”. The eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus), is redbrown or gray-brown in appearance, having large hind feet, with a fluffy white tail, hence the name “cottontail”. Its ventral surface is white, and they show their white underside of its tail 6 when it’s running. Cottontails have large ears, eyes, and incisors. They undergo two molts a year, one being in spring with a short summer coat of red-brown and the other in the winter with a longer gray-brown pelage. An adult cottontail can reach 16.5 inches in length and 2-4 pounds. A female (doe) is larger than the male (buck) cottontail. Figure 4 and 5: Eastern Cottontail Rabbits Cottontails have a breeding season beginning in March which will run until late summer. They have a gestation period of 28 to 29 days, but can also range between 25 to 35 days. The average litter size is 3 to 4, but can range from 1 to 7. The number of litters per year is 3 to 4 (Chapman, Hockman, Ojeda 1980). At birth, the young are about 4 inches long and weigh approximately one ounce, covered with fine hair, blind, deaf, and completely helpless. The young are able to leave the nest 14 to 16 days after birth (Chapman, Hockman, Ojeda 1980). Cottontails experience high mortality each year of up to 80% (Wildlife Habitat Council 1999). Cottontails build nests in slanting holes that contain an outer lining of grass, or herbaceous stems, with an inner lining of fur. Eastern cottontails in Michigan display a spring change from woody winter cover to upland herbaceous cover for the creation of nest sites (Chapman, Hockman, Edwards 1982). Limits in the breeding season are related to the availability of vegetation (Chapman, Hockman, Ojeda 1980). The eastern cottontail eats a wide variety of food depending on the seasons of green vegetation and woody plants. Herbaceous species were eaten during the growing season, and woody species were eaten during the dormant season (Chapman, Hockman, Ojeda 1980). 7 Winter food sources include winter wheat, oats, buds, branch tips, bark of blackberry, raspberry, sumac, dogwood, maple, etc. In the spring, summer, fall, food includes native and introduced grasses such as wheatgrasses, orchard grass, timothy, bluegrasses. Various fruits, wild strawberry, dandelion, sedges, and white clover are also eaten (Wildlife Habitat Council 1999). Cottontails will also eat garden vegetables, such as green beans, peas, lettuce, cabbage, and others when given the occasion (Wildlife Habitat Council 1999). The cottontail has many predators which include the, domestic dog, fox, coyote, bobcat, domestic cat, weasel, raccoon, skunk, mink, owl, hawk, snake, and humans. They are also susceptible to a variety of diseases and parasites, such as tularemia, rabbit tapeworm, fibroma, sarcocystis, and ticks and fleas. Tularemia is a bacterial disease, and can be potentially serious to humans if untreated. This infectious disease can be transmitted through bites of flies, lice, and fleas to cottontails as well as humans. Hunters should be aware of rabbit behavior and handle with care an infectious rabbit to minimize exposure (Yeatter, Thompson 1952). Rabbit tapeworms (Cittotaenia variabilis), reaches the adult stage in the cottontail’s digestive tract. They are flat, segmented tapeworms, but there is no evidence that they create serious problems to the host (Lyman 1902). Fibromas are fibrous tumors on the skin and are usually found on rabbits’ nose, legs, ears and feet. They are transmitted by biting insects, and are harmless to humans (Dalmat, Cunningham 1959). Whitish streaks in the muscles of rabbits are cysts of the genus Sarcocystis. There is no evidence that it is a threat to humans, and the parasites are destroyed by cooking the cottontail (Erickson 1946). Habitat and Range Habitat preference vary from season to season, between latitudes and regions, and with differing behavioral activities (Chapman, Hockman, Ojeda 1980). The eastern cottontail inhibits a wide range of successional and transitional habitats (Chapman, Hockman, Edwards 1982). Cottontails thrive off of dense vegetation growing as edge between woody vegetation and open grasslands. Dense grasses and forbs growing along open fields, meadows, orchards, farmlands, fence rows, stands of deciduous trees, low growing brush, shrubs, vines, and hedgerow thickets are preferred. Open grasslands offer areas of resting cover, and protection from predators and weather. Escape cover is essential and can be provided by dense underbrush, low growing and thorny vines and bushes. Cottontails can also be found in abandoned orchards, old homesites 8 and suburbs. Home ranges vary in size and are affected by habitat stability and dispersion food and cover, age, sex, and competition. Their range may vary from one to sixty acres, but averaging around six to eight acres for males and two to three for females (Chapman, Hockman, Ojeda 1980). The eastern cottontail occurs sympatrically with six other species of Sylvilagus and six species of Lepus. The eastern cottontail has the ability to occupy diverse habitats and has the widest distribution of them. The cottontail is found in most of the eastern United States, southern Canada, and as far down as South America (Chapman, Hockman, Ojeda 1980). Figure 6: Distribution of Sylvilagus floridanus. Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) Life History Sciurus carolinensis, or eastern gray squirrel, is a medium sized tree squirrel that is typically medium gray in color but can have color variations from black to cinnamon-brown or black with a cinnamon tail. Albinism also occurs in the gray squirrel, although it is not common. Gray squirrels range in length from 14.96 to 20.67 inches with up to half their length coming from their long, bushy tails. Grey Squirrels typically range in weight from 1-3 lbs. 9 E. gray squirrels spend most of their lives in the treetops descending down to feed and store food or move from tree to tree. Gray squirrels are mainly active in the hours just after sunrise and just before sunset. Gray squirrels also live in trees where they build a nest of leaves and twigs (called a dray) in the fork of a tree which is used during the summer and fall months. During the winter and spring months, gray squirrels live in a hollow portion of the tree where they den up for hibernation or raising their young. Gray squirrels feed mostly on nuts, flowers and buds of oaks, hickory, pecan, walnut and beech tree species. Gray squirrels also consume the fruits, seeds, bulbs or flowers of maple, mulberry, hackberry, elm, bucky, horse chestnut, wild cherry, dogwood, hawthorn, black gum, hazelnut, hop hornbeam and gingko trees. The gray squirrel also feeds on the seeds and catkins of certain gymnosperms such as cedar, hemlock, pine, and spruce. Gray squirrels also eat a variety of herbaceous plants and fungi. In agricultural areas crops, such as corn and wheat, are readily eaten, especially during the winter months. During the summer months insects are eaten and are probably especially important for juvenile gray squirrels. Gray squirrels will eat other gray squirrels although highly unlikely, and may also eat bones, bird eggs and nestlings, as well as frogs. Gray squirrels bury food in winter caches using a method called scatter hoarding and locate these caches using both memory and smell. These caches when forgotten by the squirrels are thought to be important for the dispersal of many different seeds which leads to the growth of many trees. Gray squirrels normally mate during two time periods per year; once during the months of December-February and again during the months of May-June. Males will “court” females for up to 5 days before the female enters estrous. Once the female enters estrous the pair will breed. Females have a gestation period of 44 days. Gray squirrels produce two liters of two-four young twice during each breeding season. Eastern gray squirrels are preyed upon by a variety of predators ranging from weasels to coyotes to bobcats to hawks (Lawniczak 2002). 10 Figure 7: Eastern Gray Squirrel Figure 8: Eastern Gray Squirrel (black color phase) Habitat and Range The Eastern Gray Squirrel, Sciurus carolinensis, is a native species to central and eastern North American spanning from southern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Gray squirrels have been successfully introduced to western N. America as well as Europe, S. Africa, and Australia. The gray squirrel’s preferred habitat is continuous, mature hardwoods and mixed forest types common throughout much the squirrels’ range, preferably with mast producing trees such as oaks, walnut, beech, etc. An understory consisting of a diverse mix of vegetation is also preferred. Gray squirrels can tolerate highly fragmented landscapes and are therefore found in urban areas as well. Figure 9: Native distribution map of Sciurus carolinensis 11 Management Goals and Objectives Maintain stable populations of North American porcupines, Eastern gray squirrels, and Eastern cottontails through habitat improvements. Maintain corridors/edges between woody vegetation and open grassland. Preserve dead-standing snags and downed logs for dens. Conduct an uneven-aged management selection technique (thinning) timber harvest of 100 acres of northern hardwood and lowland hardwood trees to open up the canopy and provide ground cover for all species. Limbs from felled trees are utilized to construct brush piles for cover/dens. Mowing/disking of upland areas to stimulate new growth. Area Description General: Figure 10: Map of Neithercut woodland Neithercut woodland is located on the south side of M-115 in Farwell, 30 minutes north of Mount Pleasant, Michigan, in Clare County. It contains 252 acres of diverse habitats, such as conifer plantations, fields and meadows, cedar and shrub swamps, hardwood forests, beaver flowages, a creek and a vernal pond. The vernal pond is a temporary pond which forms after the first thaw and rains of the spring. It accommodates many species of frogs and other amphibians. The cedar swamp is an important aspect of the woodland, because it provides plenty of shelter for many species. Also, it provides the area with a continual source of necessary water. 12 Neithercut includes four marked trails, the Arborvitae Trail, Brookwood Trail, Freedom Path, and the Littlefield Trail for outdoor recreation and education. There are two creeks that flow throughout Neithercut, but the main stream that flows southwest throughout the woodland is Elm Creek. Elm Creek is a very narrow spring-fed water system, and is important ecologically because it supports a Brook Trout population. The hills and deep ravines of the woodland were largely determined by the effects of the massive glaciers that covered the Great Lakes region over ten thousand years ago. Neithercut woodland supports a very diverse community of various mammal, bird, amphibian, fish, insect, and reptile species. Neithercut History Figure 11: Photograph of Josiah Littlefield Josiah L. Littlefield owned the Neithercut woodland in 1871. He was very dedicated to conservation, which shows up in his preservation of his woodland. After Littlefield’s death in 1936 his family transferred almost 252 acres to Central Michigan University in the years of 1959-1968. A Flint banker, William Neithercut, was a former president of the CMU Alumni Association. Neithercut was a very important factor in donating the necessary funds to maintain the woodland, which in turn helped to provide future educational opportunities for CMU students as well as others. The Wakelin McNeel Nature Center, built in 1973, is located in the Neithercut woodland, and it is a very useful location for educational public outreach. 13 Soils Figure 12: Soil types of Neithercut woodland. 14 The soil types in Neithercut woodland consist primarily of McBride Sandy Loam, Menominee Loamy Sand, Au Gres Loamy Sand, Sims Clay Loam, Nester Loam, Lupton Muck, Montcalm Loamy Sand, and Graycalm Sand. Vegetation Figure 13: Landuse/cover types of Neithercut woodland There are many tree and shrub species found in the Neithercut woodland. The tree species are American Basswood, American Beech, American Elm, Bitternut Hickory, Black Cherry, Black Willow, Eastern Hemlock, Ironwood, Jack Pine, Largetooth Aspen, Musclewood, Paper Birch, Red Maple, Red Oak, Red Pine, Scotch Pine, Silver Maple, Sugar Maple, Tamarack, Trembling Aspen, White Cedar, and White Pine (See appendix for scientific names). The shrub species are Blackberry, Choke Cherry, Common Elder, Dogwood, Juneberry, Michigan Holly, Red Osier Dogwood, Speckled Alder, Staghorn Sumac, Sweet Fern, and Witch Hazel (See appendix for scientific names). There are also many different types of herbaceous 15 plants, mosses, fungi, and ferns found throughout the woodland (See appendix for scientific names). Past and Present Land Conditions Various areas in the northwest area of the Neithercut woodland were used at one time as a landing area for logging. The majority of the Brookwood Trail was formed by a railroad grade that was used to transport logs. The land in Clare County has historically been used for the timber industry, agriculture, and oil drilling. After the timber industry died out the soil was nurtured back to productivity by the farmers. Also, during the 1930’s large oil fields were discovered. Currently the land in Neithercut woodland is used for educational and recreational purposes. It is being preserved in its natural state by Central Michigan University, and there are four hiking trails for people to use. Highway M-115 borders the property to the north, and US10 junction borders it to the east. A gravel driveway leads from M-115 to the Wakelin McNeel Nature Center. The current habitat/land cover is ideal for the managed species, and management goals. Therefore, there are no major potential limiting factors of the habitat for the managed species. Figure 14: Land Cover of Neithercut woodland 16 Management Recommendations Overall Goal The main goal of this management plan is to maintain a stable population of Eastern cottontails, North American porcupine, and Eastern gray squirrels through habitat improvements to Neithercut woodland. Maintain corridors/edges between woody vegetation and open grassland This objective will be carried out by using prescribed burns in areas where open grasslands meet the tree lines. This will prevent feathering affects between the two systems that will ensure the maintenance of distinct edges/transition zones. These burns will be conducted during the spring of the year to prevent fires from spreading out and threatening other areas of Neithercut. These fires will also take place on a rotational basis so that it will provide different successional stages throughout this habitat. Preserve dead-standing trees (snags) and downed trees or logs for dens This objective will be carried out by making sure that naturally dead, standing or downed trees are not accidentally taken down or removed either by the proposed timber harvest or by CMU Neithercut authorities. This will ensure denning and cover sites for the species being managed. Conduct an uneven-aged management selection technique (thinning) timber harvest of approximately 100 acres of northern hardwood and lowland hardwood trees to open up the canopy and provide ground cover for all species 17 Figure 15: Proposed thinning areas in Neithercut woodland This timber harvest will be conducted to thin the existing sections of Northern hardwoods and lowland hardwoods found on the Neithercut property. This will open up the forest canopy allowing light to penetrate and for the understory to grow up. This in turn will provide both food and cover in the form of emergent herbaceous vegetation as well as shrubs for all the managed species. This timber harvest can be conducted every 50-60 years which will ensure new growth as well as veneer quality saw logs which in turn will help offset the cost of all the proposed management objectives. “Properly managed long rotations in which merchantable trees are removed and natural reproduction periodically thinned can provide ideal small game habitat” (Yarrow 2009). 18 Limbs from felled trees are utilized to construct brush piles for cover/dens This objective will be carried out by using the leftover limbs, branches, and other slash from the logging operations to construct brush piles throughout the Neithercut woodland. This operation will benefit all species in the management plan by providing denning, cover, and hiding spots from predators. The brush piles will be constructed by basically gathering up and throwing a bunch of the slash material in a pile, but ensuring bigger sized limbs as the base from the brush pile so that the species can move about inside of the brush pile. The brush piles will be built on a basis of one brush pile for every five acres, ensuring fifty brush piles located throughout Neithercut. Figure 16: Brushpile construction steps 19 Mowing/disking of upland areas to stimulate new growth Figure 17: Mowing/Disking strategies This objective will be carried out by simply mowing or disking the open grassland areas in strips. This will be done every year but only to certain areas (strips) of the grassland. Each strip will be of a different size and shape according to how the grassland is laid out. This will be done for a period of five years where then it will be decided if further mowing/disking is necessary. Evaluation Techniques & Monitoring Plans Eastern gray squirrel The evaluation techniques that will be used to determine how well or not well the habitat improvements worked are: 1) Visual method, 2) hair-tube surveys, and 3) Drey counts. The visual method involves “making standardized ‘time–area’ counts of squirrels using direct sightings. If the surveys are carried out each season over a number of years this technique can be effective in monitoring changes in squirrel populations over time. It is best to carry out visual surveys in late winter/spring in broadleaved woodlands, if it is not possible to carry out surveys in every season of the year, as visibility is limited when trees are in leaf. ” (Gurnell et al, 2009). The hair-tube survey involves “specially adapted lengths of plastic drainpipe which are baited to attract squirrels. Hairs are collected on sticky tapes inside the tubes as the animals enter the tubes to get the food. Collected hair is removed from the tubes periodically for examination. Hair tubes are good for detecting the presence of squirrels and if calibrated by carrying out comparative trials with other methods can provide an index of population trends.” (Gurnell et al., 20 2009). The process for making these trap is as follows: 1. Make the hair tubes from 300 mm lengths of plastic drainpipe: 65 mm diameter round, or 65 mm x 65 mm square ended. 2. Place a wooden or plastic block (2.5 x 2.5 x 0.5 cm) covered with double-sided sticky tape inside the roof at either end of each tube around 3 cm in from the entrance. Hold the blocks in place with the sticky tape or clips made out of fencing wire. 3. Attach the tubes to the branches of trees at a convenient height, i.e. it should not be necessary to use a ladder. The tubes can be attached using wire, straps or terry clips. Clips allow the tubes to be removed and replaced quickly. 4. Use up to 20 tubes to survey an area of woodland by placing them 100–200 m apart in lines or in a grid pattern. A standard number of tubes should be used for each site in any survey. 5. Bait the tubes sparingly using sunflower seeds, peanuts or maize, once at the start of the survey. 6. Retrieve and number by location the sticky blocks after a standard time period (such as 3, 7 or 14 days). Protect the hairs by covering the blocks with a strip of waxed paper or polythene sheet to prevent them being damaged. 7. Leave the tubes in place if needed for future surveys. Figure 18: Hair Collection Tube The last method for monitoring the gray squirrel is the drey count. Drey counts “are used to establish the presence of squirrels in a forest or woodland. Active dreys are a reliable indication of squirrel presence, and the density of dreys can give some idea of squirrel numbers. Dreys tend to be semi-permanent when squirrels are resident, and thus the number of dreys tends 21 to reflect squirrel numbers over a season, a year or even longer.” (Gurnell et al., 2009). These techniques will be carried out yearly in the late winter/early spring. North American Porcupine The most useful and most efficient method for counting porcupine populations is by doing a visual count. Porcupines in Neithercut will den in either standing dead hollow trees (snags) or brush piles. Volunteers can walk around and check the man-made dens for signs of porcupine activity, or the porcupines themselves. Another obvious way to determine porcupine nesting sites is by looking for scat piles at the base of snag trees. Because porcupines generally do not den together socially, it can be assumed that there is only one porcupine per nesting site (Weber, C. and P. Myers. 2004). The dens can be checked yearly in the winter so that there is less vegetation cover, which will make the porcupines more easily visible. Eastern cottontail rabbit To begin our monitoring of Eastern cottontail rabbits, we should map and record our land areas and identify rabbit feeding areas, burrows, rivers, streams, brush piles, areas of low, medium, high rabbit infestation, rabbit free areas, boundary fences (rabbit proof/ not rabbit proof). There are a number of different types of monitoring that can be used. The common and simple methods are spotlight transects, warren monitoring, warren/rabbit counts, and the Gibb and McLean Scales (Bloomfield 1999). Spotlight transect counts give a good sign of the general numbers and density of rabbits across the spotlighted area. Spotlight transects can only provide an index of changes in rabbit numbers and are not a measure of absolute population levels in an area. (Bloomfield 1999). Spotlight counts must be done on at least two consecutive nights. There can be a variable of results, because of weather, changes in vegetative cover and differences in spotlighting techniques by different people. We should do the spotlight transect every 4 months in off breeding season and at least every month during breeding season. The Warren monitor site counts active and non-active entrances. We count how many burrows are active or non-active over a period of time. The basic estimate for a warren system is that for each three active entrances there is one rabbit (Bloomfield 1999). The Warren/rabbit counts, involves counting rabbits that emerge from warrens at specific times. This method can also be used to determine breeding season and disease outbreaks. One must count the number of juvenile, sub-adult, and adult cottontails from a warren in an elevated and hidden position 22 (Bloomfield 1999). Another method used to monitor cottontails is the Gibb and Mclean Scales. Gibb is a scale of sign, such as rabbit droppings, and Mclean is also a scale of sign, but of rabbit numbers. Both these scales can be used to point out relative rabbit abundance (Bloomfield 1999). Integrating all of these monitoring methods will help with a more accurate assessment. Criteria for Identifying Success The criterion for identifying success for this management plan is pretty straightforward. If it is determined through the yearly population counts of the species that it there are stable populations, then the management plan will be deemed successful. There will be slight variations from year to year, but as long as the numbers do not change drastically then the populations can be assumed stable. In conclusion, as long as the population counts show signs of these species present in Neithercut there will be no additional management strategies implemented. Timeline Year One: Spring – 2010 Meeting with foresters to survey the land for the timber harvest. Summer -2010 Open up bidding to local timber companies for the woodland. Winter – 2010 Initial population counts conducted of the species. Year Two: Spring – 2011 Initial mowing/disking of a strip of open grassland. Summer – 2011 Timber harvest conducted. Fall – 2011 Brush piles constructed from slash results of timber harvest. 23 Winter – 2011 Second population counts conducted of the species. Year Three: Spring – 2012 First prescribed burn takes place in the upland grassland. Second mowing/disking of a strip of open grassland. Winter – 2012 Third population counts conducted of the species. Year Four – Six: Continue steps previously taken throughout the first three years (except timber harvest). Year Seven: Reevaluate management plan to determine if it should be continued, altered, or discontinued. Budget The equipment annual costs for this management plan are summarized in Table 1. The first year’s expenses will be covered by applying for grants from either the U.S Department of Agriculture or the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service. If need be this plan could also take out a small loan from a local bank, which could be easily paid off following the timber harvest and the revenue from that. The benefits to CMU are an increase in the biodiversity of Neithercut Woodlands ecosystem, and to continue to provide educational opportunities for CMU students as well as the surrounding communities. This management plan will also benefit CMU by donating several thousand dollars to the CMU Biology Department (you’re welcome). The appraised value for the timber sale was estimated using present timber sale bids of state land forests conducted by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Environment (MDNRE). 24 Figure 19: Timber Sale Bid Report 25 References http://www.mymichigangenealogy.com/mi-county-clare.html#eh http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Sciurus_carolinensis.html. Bloomfield, T. 1999. Rabbit: monitoring rabbit populations. Department of Primary Industries http://new.dpi.vic.gov.au/home Chapman, J.A., J.G. Hockman, and M.M. Ojeda C. 1980. Sylvilagus floridanus. Mammalian Species 136: 1-8. Chapman, J.A., J.G. Hockman, and W.R. Edwards. 1982. Pages 83-123 in J.A. Chapman and G.A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: Biology, management, Economics. John Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, MD. Erickson, A.B. 1947. Helminth parasites of rabbits of the genus Sylvilagus. J. Wildl. Mgmt., 11:255-263. Fyvie, A., and E.M. Addison. 1979. Manual of common parasites, diseases and anomalies of Wildlife in Ontario. Ontario Min. Nat. Resour. Ottawa, Ont. 120pp. Gorton, P.B. 1978. Land Use and Interpretation at Neithercut Woodland. Thesis for the Degree of M.S. Central Michigan Univeristy. Gurnell, J., Lurz, P.W.W., Pepper, H., 2009. Practical Techniques for Surveying and Monitoring Squirrels. Forestry Commission Practical Notes, no. 11, 12 pp. Kurta, A. 1995. Mammals of the Great Lakes Region. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Lawniczak, M. 2002. "Sciurus carolinensis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web AccessedNovember 29, 2009 at. Pejza, J. 2003. Neithercut Woodland: A Conservation Education and Environmental Interpretation Facility. www.cst.cmich.edu/centers/niethercut Roze, U. 1989. The North American Porcupine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. Squirrels. Forestry Commission Practical Notes, no. 11, 12 pp. Sweitzer, R. 2003. Breeding movements and reproductive activities of porcupines in the Great Basin Desert. Western North American Naturalist, 63/1: 1-10. Sweitzer, R., S. Jenkins, J. Berger. 1997. Near-Extinction of porcupines by mountain lions and consequences of ecosystem change in the Great Basin Desert. Conservation Biology, 11/6: 1407-1417. 26 Weber, C. and P. Myers. 2004. "Erethizon dorsatum" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed November 29, 2009 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Erethizon_dorsatum.ht ml. Wildlife Habitat Council. 1999. Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus). Wildlife Habitat Management Institute, Washington, D.C., USA. Woods, C. A. 1973. Erethizon dorsatum. Yeatter, R.E., and D.H. Thompson. 1952. Tularemia, weather, and rabbit populations. Nat. Hist. Surv. Bull. 25(6): 351-382. Tables & Figures Figures 1. http://www.animalwebguide.com/Porcupine-1.jpg 2. http://blackramfarm.files.wordpress.com/2008/10/porcupine-1.jpg 3. Parks Canada/B. Morin/06.60.10.01(01) 4. http://thundafunda.com/3993/images/animals/wild-animals-cute/baby-eastern-cottontailrabbit-indiana-pictures.jpg 5. http://psp.88000.org/18_-_Baby_Eastern_Cottontail_Rabbit.htm 6. http://en.wikipedia.org.wiki.File:Florida-walkaninchen-world.png 7. http://www.snowmancam.com/images/grey_squirrel.jpg 8. http://farm4.static.flickr.com/3348/3257206925_7b07f350e7.jpg 9. http://www.mnh.si.edu/mna/image_info.cfm?species_id=298 10. www.googleearth.com 11. http://neithercut.bio.cmich.edu/images/littlefield.jpg 12. http://www.mcgi.state.mi.us/mgdl/?rel=cext&action=Clare 13. www.google.com 14. www.google.com 15. www.google.com 16. http://www.dnr.state.md.us/wildlife/wabrush.gif 27 17. Wildlife Habitat Council. 1999. Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus). Wildlife Habitat Management Institute, Washington, D.C., USA. 18. Gurnell, J., Lurz, P.W.W., Pepper, H., 2009. Practical Techniques for Surveying and Monitoring Squirrels. Forestry Commission Practical Notes, no. 11, 12 pp. 19. http://www.michigandnr.com/ftp/forestry/tsreports/bidopen/2009/Gaylord%20Office/Gay lord%20Office%202009-11-18.PDF Tables Table 1. Neithercut Management Budget Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Year 6 Prescribed Burning 0 0 967.83 967.83 967.83 967.83 Timber Harvest $50/hr*12hr = $600 total 0 0 0 0 0 Brushhog Rental 0 47.50/day 47.50/day 47.50/day 47.50/day 47.50/day Tractor Rental 0 257.00/day 257.00/day 257.00/day 257.00/day 257.00/day Squirrel Trap Equipment 300 0 0 0 0 0 Flashlights 150 0 0 0 0 0 Fuel 0 75 75 75 75 75 Miscellaneous/ Maintenance Costs 100 100 100 100 100 100 Labor 200 200 200 200 200 200 Totals $1,350.00 $679.50 $1,647.33 $1,647.33 $1,647.33 $1,647.33 Total Costs $8,618.82 Income from Timber Harvest 0 Approximately 0 0 0 0 Net Total $41,381.18 50,000 28 Appendix A Mammals Blarina brevicauda Shorttail Shrew Canis latrans Coyote Castor canadensis Beaver Citellus tridecemlineatus 13-Lined Ground Squirrel Erethizon dorsatum Porcupine Glaucomys sabrinus Northern Flying Squirrel Lepus americanus Snowshoe Hare Marmota monax Woodchuck Mephitis mephitis Striped Skunk Microtus pennsylvanicus Meadow Vole Mustela frenata Longtail Weasel Mustela vison Mink Myotis lucifugus Little Brown Bat Napaeozapus insignis Woodland Jumping Mouse Odocoileus virginianus Whitetail Deer Ondatra zibethica Muskrat Peromyscus leucopus White-footed Mouse Procyon lotor Raccoon Scalopus aquaticus Eastern Mole Sciurus carolinensis Eastern Gray Squirrel Sciurus niger Eastern Fox Squirrel Sorex cinereus Masked Shrew Sylvilagus floridanus Eastern Cottontail Tamiasciurus hudsonicus Red Squirrel Tamias striatus Eastern Chipmunk Taxidea taxus Badger Vulpes fulva Red Fox Birds Acanthis flammea Common Redpoll Accipiter cooperii Cooper’s Hawk Agelaius phoeniceus Red-winged Blackbird Aix sponsa Wood Duck Ammodramus henslowii Henslow’s Sparrow Anas discors Blue-winged Teal Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Ardea herodias Green Blue Heron Asio otus Long-eared Owl Bartramia longicauda Upland Sandpiper Bombycilla cedrorum Cedar Waxwing Bonasa umbellus Ruffed Grouse Bubo virginianus Great Horned Owl Buteo jamaicensis Red-tailed Hawk Butorides virescens Green Heron Cardinalis cardinalis Cardinal Capella gallinago Common Snipe Caprimulgus vociferus Whip-poor-will Carpodacus purpureus Purple Finch 29 Certhia familiaris Brown Creeper Charadrius vociferus Killdeer Chordeiles minor Common Nighthawk Circus cyaneus Marsh Hawk Cistothorus platensis Short-billed Marsh Wren Colaptes auratus Common Flicker Contopus virens Eastern Wood Pewee Coragyps aura Turkey Vulture Corvus brachyrhynchos Common Crow Cyanocitta cristata Blue Jay Dendrocopos pubescens Downy Woodpecker Dendrocopos villosus Hairy Woodpecker Dendroica coronata Yellow-rumped Warbler Dendroica petechia Yellow Warbler Dendroica virens Black-throated Green Warbler Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bobolink Dryocopus pileatus Pileated Woodpecker Empidonax traillii Least Flycatcher Eremophila alpestris Horned Lark Falco sparverius American Kestrel Geothlypis trichas Common Yellowthroat Hesperiphona vespertina Evening Grosbeak Hylocichla mustelina Wood Thrush Icterus galbula Northern Oriole Iridoprocne bicolor Tree Swallow Junco hyemalis Dark-eyed Junco Lanius excubitor Northern Shrike Megaceryle alcyon Belted Kingfisher Melanerpes erythrocephalus Red-headed Woodpecker Melospiza melodia Song Sparrow Mniotilta varia Black-and-white Warbler Molothrus alter Brown-headed Cowbird Nyctea scandiaca Snowy Owl Otus asio Screech Owl Parus atricapillus Black-capped Chickadee Parus bicolor Tufted Titmouse Passer domesticus House Sparrow Passerella iliaca Fox Sparrow Passerina cyanea Indigo Bunting Pheucticus ludovicianus Rose-breasted Grosbeak Philohela minor American Woodcock Pinicola enucleator Pine Grosbeak Pipila erythrophthalmus Rufous-sided Towhee Pirango olivacea Scarlet tanager Plectrophenax nivalis Snow Bunting Pooecetes gramineus Vesper Sparrow Quiscalus quiscula Common Grackle Regulus satrapa Golden-crowned Kinglet Riparia riparia Bank Swallow Sayornis phoebe Eastern Phoebe Seiurus aurocaapillus Ovenbird Setophaga ruticilla American Redstart Sialia sialis Eastern Bluebird 30 Sitta canadensis Red-breasted Nuthatch Sitta carolinensis White-breasted Nuthatch Sphyrapicus varius Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Spinus tristis American Goldfinch Spizella arborea Tree Sparrow Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow Spizella pusilla Field Sparrow Strix varia Barred Owl Sturnella magna Easern Meadowlark Toxostoma rufum Brown Thrasher Troglodytes aedon House Wren Turdus migratorius American Robin Tyrannus tyrannus Easetern Kingbird Vermivora ruficapilla Nashville Warbler Vireo olivaceus Red-eyed Vireo Zenaida macroura Mourning Dove Zonotrichia albicollis White-throated Sparrow Zonotrichia leucophrys White-crowned Sparrow Reptiles Chrysemys picta Painted Turtle Diadophis punctatus Ring-neck Snake Heterodon platyrhinos Hog-nose Snake Lampropeltis triangulatum Eastern Milk Snake Opheodrys vernalis Eastern Smooth Green Snake Storeria occipitomaculata Northern Red-bellied Snake Thamnophis sauritus Eastern Ribbon Snake Thamnophis sirtalis Eastern Garter Snake Amphibians Ambystoma laterale Blue-spotted Salamander Bufo americanus American Toad Hemidactylium scutatum Four-toed Salamander Hyla crucifer Northern Spring Peeper Plethnodon cinereus Red-backed Salamander Pseudacris triseriata Western Chorus Frog Rana clamitans Green Frog Rana sylvatica Wood Frog Fish Clinostomus elongatus Redside Dace Cottus bairdi Mottled Sculpin Lampetra lamottei American Brook Lamprey Lepomis cyanellus Green Sunfish Lepomis gibbosus Pumpkinseed Notemigonus crysoleucas Golden Shiner Rhinichthys cataractae Longnose Dace Salvelinus fontinalis Brook Trout Salmo trutta Brown Trout Umbra limi Common Mudminnow 31 Appendix B Trees and Shrubs Acer rubum Red Maple Acer spicatum Mountain Maple Alnus rugosa Speckled Alder Amelanchier sp. Serviceberry Betula papyrifera Paper Birch Cornus alternifolia Alternate-leaved Dogwood Cornus racemosa Pinacled Dogwood Cornus stolonifera Red-osier Dogwood Crataegus sp. Hawthorn Larix laricina Tamarak Picea canadensis White Spruce Pinus sylvestris Scotch Pine Populus balsamifera Balsam Poplar Populus deltoides Cottonwood Populus grandidentata Big-toothed Aspen Populus tremuloides Trembling Aspen Rhus typhina Stag-horn Sumac Rhus radicans Poison Ivy Ribes floridum Black Currant Sambucus canadensis Elderberry Taxus canadensis American Yew Tilia americana American Basswood Thuja occidentalis N. White-cedar Ulmus americana American Elm Ulmus rubra Slippery Elm Vibernum acerifolium Maple-leaf Viburnum Vibernum lentago Nannyberry Vitis sp Grape Herbaceous Plants Achillea millefolium Yarrow Alopecurus geniculatus Marsh Foxtail Ambrosia artemisiifoilia Ragweed Andropogon gerardi Big Bluestem Andropogon scoparius Little Bluestem Arctium lappa Great Burdock Arctium minus Common Burdock Asclepias incarnata Swamp Milkweed Asclepias syriaca Common Milkweed Aster novae-angliae New England Aster Avena fatua Wild Oats Berteroa incana Hoary Alyssum Bidens sp. Sticktights Brassica campestris Field Mustard Capsella Bursa-pastoris Shepherd’s Purse Cenchrus longispinus Sandbur Cerastium vulgatum Mouse-ear Chickweed Chrysanthemum Leucanthemum Ox-eye Daisy 32 Crisium arvense Canada Thistle Cirsium vulgare Bull Thistle Clematis virginiana Virgin’s Bower Convolvulus sepium Hedge Bindweed Cornus canadensis Bunchberry Cypripedium sp. Lady-slipper Daucus carota Wild Carrot Eleocharis sp. Spike Rush Equisetum scirpoides Sedge-like Equisetum Equisetum pilosa Small-tufted Love Grass Erigeron philadelphicus Daisy Fleabane Eryngium yuccifolium Rattlesnake-master Eupatorium perfoliatum Boneset Eupatorium purpureum Joe Pye Weed Fragaria virginiana Common Strawberry Gaultheria procumbens Wintergreen Goodyera pubscens Downy Rattlesnake Plantain Helenium autumnale Sneezeweed Helianthus giganteus Tall Sunflower Hordeum jubatum Squirrel-tailed Grass Impatiens biflora Jewel-weed Iris versicolor Large Blue Flag Iris Lepidium virginicum Peppergrass Liatris sp. Blazzing Star Lycopodium complanatum Trailing Christmas-green Maianthemum canadensis Canada Mayflower Marchantia sp Liverwort Melilotus alba White Sweet Clover Mitchella repens Partridgeberry Oenothera biennis Evening Primrose Panicum capillare Old Witch Grass Poa annua Spear Grass Polygala paucifolia Fringed Polygala Polygonum pensylvanicum Knotweed Potentilla recta Rough-fruited Cinquefoil Prunella vulgaris Heal-all Pyrola elliptica Shinleaf Ranunculus septentrionalis Marsh Buttercup Ranunculus acris Meadow Buttercup Rudbeckia hirta Black-eyed Susan Rudbeckia laciniata Green-headed Coneflower Setaria glauca Yellow Foxtail Grass Silphium intergrifolium Rosin Weed Silphium laciniatum Compass Plant Silphium terebinthinaceum Prairie Dock Smilacina racemosa False Solomon’s Seal Smilax hispida Hispid Greenbriar Sonchus oleraceus Common Sow Thistle Solidago gigantea Late Goldenrod Thalictrum dioicum Meadow Rue Trifolium pratense Red Clover Typha latifolia Broad-leaved Cattail Urtica dioica Stinging Nettle 33 Uvularia perfoliata Large Flowered Bellwort Vicia americana Purple Vetch Xanthium strumarium Cocklebur 34