Group 3 - Illinois During the Gilded Age

advertisement

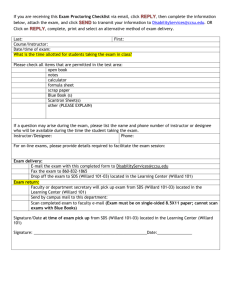

The WCTU and the Lynching Controversy GROUP 3 PACKET by Jennifer Erbach ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 1 Introduction: Ida B. Wells was an African American journalist and part-owner of the newspaper Free Speech. In 1892, after writing editorials condemning lynching, she was forced to flee the South by a mob who threatened her life. Wells traveled around Great Britian and the northern U.S. lecturing on the horrors of lynching and trying to rouse public sympathy against it. She published A Red Record in 1895, a compilation of lynching statistics. Frances Willard was a northern school teacher who became actively involved with the Women's Christian Temperance Union, an organization which worked to promote temperance, purity, moral reform, and encouraged education and women's suffrage. In 1879, she was elected president of the National WCTU and in 1891 became the president of the World WCTU. Willard traveled extensively, delivered lectures, and published pamphlets pertaining to issues of social and moral reform. In the early 1890's conflict arose between Ida B. Wells and the WCTU, particularly with Frances Willard. Wells accused the WCTU of ignoring the atrocities being committed against blacks by lynch mobs. Wells was also outraged by some of the statements made by Willard concerning racial tensions in the south, statements which appeared to excuse, if not condone, lynching. Willard in turn, accused Wells of being "overzealous" in her attacks, and of painting a distorted picture of U.S. racial tensions during her lectures in Great Britain. The conflict between the two women would last until Willard's death in 1898. Directions: Read through the documents and answer the guided reading questions included in this packet. Write down any questions that you have, and come to class prepared to discuss the readings. ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 2 "Mr. Moody and Miss Willard" The following excerpt is from an article that appeared in the British publication Fraternity in May 1894. Ida B. Wells critcized D. L. Moody, a northern preacher, arguing that because he had tolerated the southern practices of segregated churches on his visit to the south, he had "strengthened the Southern white man in his prejudices and his determination to enforce them even in the house of God." Wells then moved on to criticize Frances Willard. * * * But Miss Willard, the great temperance leader, went even further in putting the seal of her approval upon the Southerners' method of dealing with the negro. In October, 1890, the Women's [sic] Christian Temperance Union held its national meeting at Atlanta, Georgia. It was the first time in the history of the organisation that it had gone South for a national meeting, and met the Southerners in their own homes. They were welcomed with open arms; the Governor of the State and the Legislature gave special audience in the halls of State legislation to the temperance workers. They set out to capture the Northerners to their way of seeing things, and, without troubling to hear the negro side of the question, these temperance people accepted the white man's story of the problem with which he had to deal. State organisers were appointed that year, who have gone through the Southern States since then, but in obedience to Southern prejudices have confined their work to white persons only. It is only after negroes are in prison for crimes that the efforts of these temperance women are exerted without regard to "race, colour, or previous condition." No ounce of prevention is used in their case; they are black, and if these women went among the negroes for this work, the whites would not receive them. Except here and there are found temperance workers of the negro race, "the great darkfaced mobs" are left the easy prey of the saloon-keeper. There was pending in the National Congress as this time a Federal Elections Bill, the object being to give the National Government control of the national elections in the several States. Had this Bill become a law, the negro, whose vote has been systematically suppressed since 1875 in the Southern States, would have had the protection of the National Government, and his vote counted. The South would have been no longer "solid;" the Southerners saw that the balance of power which they unlawfully hold in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College, based on the negro population, would be wrested from them. So they nick-named the pending elections law the "Force Bill"-- probably because it would force them to disgorge their ill-gotten political gains-and defeated it. While it was being discussed, the question was submitted to Miss Willard: "What do you think of the race problem and the Force Bill?" Said Miss Willard: "Now, as to the 'race problem' in its minified, current meaning, I am a true lover of the Southern people-- have spoken and worked in, perhaps 200 of their towns and cities; have been taken into their love and confidence at scores of hospitable firesides; have heard them pour out their hearts in the splendid frankness of their impetuous natures. And I have said to them at such times: 'When I go North there will be wafted to you no word from pen or voice that is not loyal to what we are saying here and ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 3 now.' Going South, a woman, a temperance woman, and a Northern temperance woman-three great barriers to their goodwill yonder--I was received by them with a confidence that was one of the most delightful surprises of my life. I think we have wronged the South, though we did not mean to do so. The reason was, in part, that we had irreparably wronged ourselves by putting no safeguard on the ballot-box at the North that would sift out alien illiterates. They rule our cities to-day; the saloon is their palace, and the toddy stick their sceptre. It is not fair that they should vote, nor is it fair that a plantation negro, who can neither read nor write, whose ideas are bounded by the fence of his own field and the price of his own mule, should be entrusted with the ballot. We ought to have put an educational test upon that ballot from the first. The Anglo-Saxon race will never submit to be dominated by the negro so long as his altitude reaches no higher than the personal liberty of the saloon, and the power of appreciating the amount of liquor that a dollar will buy. New England would no more submit to this than South Carolina. 'Better whiskey and more of it,' has been the rallying cry of great dark-faced mobs in the Southern localities where Local Option was snowed under by the coloured vote. Temperance has no enemy like, for it is unreasoning and unreachable. To-night it promises in a great congregation a vote for temperance at the polls to-morrow; but tomorrow twenty-five cents changes that vote in favour of the liquor-seller. "I pity the Southerners, and I believe the great mass of them are as conscientious and kindly-intentioned toward the coloured man as an equal number of white Church members at the North. Would-be demagogues lead the coloured people to destruction. Half-drunken white roughs murder them at the polls, or intimidate them so that they do not vote. But the better class of people must not be blamed for this, and a more thoroughly American population than the Christian people of the South does not exist. They have the traditions, the kindliness, the probity, the courage of our forefathers. The problem on their hands is immeasurable. The colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt. The grog-shop is its centre of power. The safety of woman, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment, so that the man dare not go beyond the sight of their own roof-tree. How little we knew of all this, seated in comfort and affluence here at the North, descanting upon the right of everyman to cast one ballot and have it fairly counted; that well-worn shibboleth invoked once more to dodge a living issue. "The fact is that illiterate coloured men will not vote at the South until the white population chooses to have them do so; and under similar conditions they would not at the north." Here we have Miss Willard's words in full, condoning fraud, violence, murder, at the ballot box; rapine, shooting, hanging, and burning; for all these things are done and being done now by the Southern white people. She does not stop there, but goes a step further to aid them in blackening the good name of an entire race, as shown by the lines in italics. These utterances, for which the coloured people have never forgiven Miss Willard, and which Frederic Douglass has denounced as false, are to be found in full in The Voice, of October 23rd, 1890, a temperance organ published at New York City. ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 4 IDA B. WELLS. Manchester, April 5th, 1894. From Ida B. Wells, "Mr. Moody and Miss Willard," Fraternity, May 1894, pp. 1617, (Temperance and Prohibition Papers microfilm (1977) scrapbook 69, frame #395). Text on-line at http://womhist.binghamton.edu/wctu2/doc27.htm. ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 5 “Letter from Frances Willard” The following is a letter from Frances Willard to the editor of the British publication Fraternity, published on October 1, 1895. The controversy between her and Ida B. Wells would continue until her (Willard's) death in 1898. TO THE EDITOR, --It would be impossible for an association like the W.C.T.U., the central object of which is the recognition and development of the brotherhood of man, to be other than in warm sympathy with those who declare the substantial unity of the human race, and endeavour to influence public opinion in the promotion of justice and sympathy between all races, classes, creeds, and communities. It is our purpose, not only by words, but deeds, to invest our lives in the effort to help on every member of the human family toward freedom, opportunity, and every brotherly consideration. Two principles underlie all our efforts in the nearly fifty countries in which the society has obtained a foothold. The first has just been stated; and the second recognizes the autonomy of each nation and state in respect to the manner in which its work shall be conducted. In some of the Northern States it is thought best to organize in societies by themselves groups of women who speak the Scandinavian tongue, and in the Southern States colored women are organized in separate groups in the same way, by their own wish and will. They realize that by working in this manner they will develop more rapidly than they would if associated with white women, even as the W.C.T.U. itself does not admit men, because we wish to become drilled and disciplined by having the entire management of the society, so that when we are enfranchised, we shall be prepared to cooperate with men in the wider circle of Government. So far as the World’s and National W.C.T.U. officers are concerned they would gladly see white and colored women in the same societies, and no distinction is made between white and colored delegates at the Conventions. From the first, colored women have been among the Superintendents and Organizers of the National W.C.T.U. We are aware that in the Southern States as a whole, it would not be practicable to group our local members in this way, and we have reason to believe that coloured women, as a class, much prefer to affiliate with those of their own race. We have been told this repeatedly by them, and while there are exceptions to this statement, we believe it represents the current opinion of the colored people up to the present time, but we think the development that will come to the women who form these helpful groups of workers will at some time in the future lead to the closer affiliation of the two groups of women in their work. We were obliged to choose either not to organize in the South at all, or else to organize on this basis. We have done the best we could under the circumstances, and we think those who have criticized us so severely would take an altogether different view if they were better informed concerning the local situation at the South. The General Officers of the W.C.T.U. make no distinction on account of race, and the attitude of the society toward the barbarity of lynching has been more pronounced than ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 6 that of any other association in the United States, for not only has a resolution against lynching been repeatedly enacted in the general society, but in many of its State branches, while the utterances of its leaders have been made clear and unmistakable. With such a record as this, White Ribboners need not fear to abide the verdict of fair-minded men and women. --Believe me, Yours sincerely, FRANCES WILLARD From "About Southern Lynchings," Baltimore Herald, 20 October 1895 (Temperance and Prohibition Papers microfilm (1977), section III, reel 42, scrapbook 70, frame 153). Text on-line at http://womhist.binghamton.edu/wctu2/doc38.htm. ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 7 Guided Reading Questions Answer the following in 1-3 complete sentences. 1. What does Ida B. Wells claim happened when the WCTU went to Atlanta for its national meeting? How, according to Wells, is the WCTU showing prejudice against African Americans in the south? 2. According to the quote provided by Wells, how does Frances Willard view the white populations of the South? In her opinion, are they villains or victims? What reasons does she give to support her opinions? 3. According to the quote provided by Wells, how does Willard view the black populations of the South? Villains or victims? What reasons does she give to support her opinions? 4. What are Wells' reactions to the statements made by Frances Willard? ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 8 5. Frances Willard gives two principles on which the efforts of the WCTU are based. What are they? 6. What, according to Willard, are the attitudes of the officers of the WCTU towards African American members? 7. How does Willard justify segregated group meetings of the WCTU in the South? 8. What does Willard say about the attitude of the WCTU regarding lynching? ©2003 Illinois During the Gilded Age Digitization Project. 9