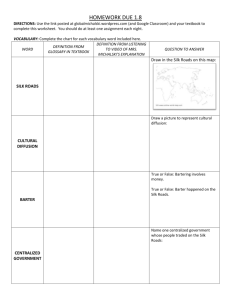

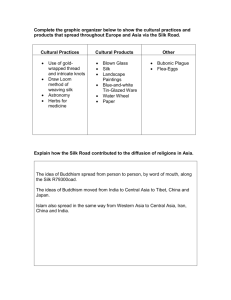

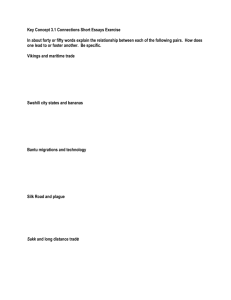

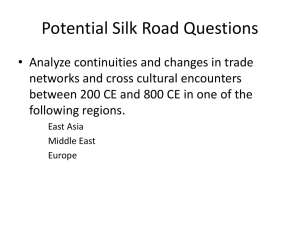

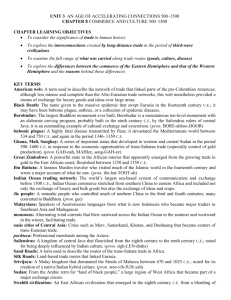

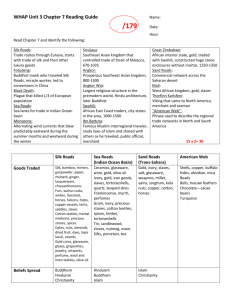

The exchange of goods among communities occupying

advertisement