Chronic Care Programme

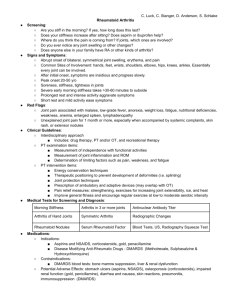

advertisement

Chronic Care Programme Treatment guidelines Rheumatoid Arthritis Chronic condition Consultations protocols Preferred treating provider Notes preferred as indicated by option referral protocols apply Maximum Treating doctor: consultations per General annum Practitioner Initial consultation Follow-up consultation Tariff codes Maximum Treating doctor: consultations per Any preferred annum provider – see list Initial consultation Follow-up consultation Tariff codes Consultations per Treating doctor: specialist Ophthalmologist Initial consultation Follow-up consultation Tariff codes Option/plan Provider GMHPP Gold Options G1000, G500 and G200. Blue Options B300 and B200. GMISHPP General Practitioner Physician Paediatrician Cardiologist Cardiology Paediatrician Pulmonologist Orthopaedic Specialist Neurologist Neurosurgeon New Patient MILD Existing patient 1 1 0183; 0187 1 1 1 1 MILD New Patient Existing patient 1 3 0142: 0108 1 1 MILD New Patient Existing patient 1 0 0142; 0108 1 0 MILD New Patient Existing patient Physiotherapy: Treating doctor: complex evaluation/ Physiotherapist Counselling at first visit only Initial consultation Follow-up consultation Tariff codes 702 Physiotherapy: one Treating doctor: MILD New Patient Existing 1 0 MODERATE TO SEVERE New Existing patient Patient 1 0 1 1 MODERATE TO SEVERE New Patient Existing patient 1 3 1 3 MODERATE TO SEVERE New Patient Existing patient 1 0 1 0 MODERATE TO SEVERE New Patient Existing patient 1 0 1 0 MODERATE TO SEVERE New Patient Existing patient complete Physiotherapist reassessment of patient’s condition during the course of treatment, and/or counselling of patient or his family Initial consultation Follow-up consultation Tariff codes 1 2 1 1 patient 1 3 1 3 703 Investigations protocols Type Provider Tariff code Peripheral fundus examination with indirect ophthalmoscope (ophthalmologist) Urine dipstick (per stick, irrespective of the number of tests on stick) Blood glucose ECG without effort Flow volume test: inspiration / expiration ESP or CRP Rheumatoid factor Haemoglobin estimation Leucocytes: total count Platelets AST ALT GGT Alkaline phosphates Serum albumin Serum potassium Serum sodium Serum urea Serum creatinine X-ray hand X-ray foot CXR ICD 10 coding Ophthalmol ogist GP, Specialist, Pathologist GP, Specialist, Pathologist GP or Specialist (see list) GP or Specialist (see list) GP, Specialist, Pathologist Pathologist GP, Specialist, Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Radiologist Radiologist Radiologist Maximum follow-up investigations per annum Mild Moderate to severe New patient Existing New patient Existing patient patient 3004 1 1 1 1 4188 4 2 4 4 4057; 4050 1 1 1 1 1232 1 0 1 1 1186 1 0 1 0 3743; 3947 4 2 4 4 4182 1 1 1 1 3762 6 4 6 6 3785 3797 4130 4131 4134 4001 3999 4113 4114 4151 4032 6500 6511 3445 6 6 6 6 6 1 1 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 4 4 4 4 4 1 1 2 2 2 2 0 0 1 6 6 6 6 6 1 1 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 6 6 6 6 6 1 1 2 2 2 2 0 0 1 M05. M06. M08. General Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder that causes the immune system to attack the joints, causing inflammation (arthritis), and some organs, such as the lungs and skin. It can be a disabling and painful condition, which can lead to substantial loss of functioning mobility due to pain and joint destruction. It is diagnosed with blood tests (especially a test called rheumatoid factor) and X-rays. Diagnosis and long-term management are typically performed by a rheumatologist, an expert in the diseases of joints and connective tissues.[1] Various treatments are available. Non-pharmacological treatment includes physical therapy and occupational therapy. Analgesia (painkillers) and anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as steroids, are used to suppress the symptoms, while disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are often required to reverse the disease process and prevent long-term damage. Classic DMARDs are methotrexate and sulfasalazine, but also the newer group of biologics which includes highlyeffective agents such as infliximab (Remicade), etanercept (Embrel), adalimumab (Humira), abatacept (Orencia) and rituximab (Rituxan/Mabthera).[1] The name is based on the term "rheumatic fever", an illness which includes joint pain and is derived from the Greek word rheumatos ("flowing"). The suffix -oid ("resembling") gives the translation as joint inflammation that resembles rheumatic fever. The first recognized description of rheumatoid arthritis was made in 1800 by Dr Augustin Jacob Landré-Beauvais (1772-1840) of Paris.[2] Signs and symptoms While rheumatoid arthritis primarily affects joints, problems involving all other organs of the body are known to occur. Extra-articular ("outside the joints") manifestations occur in about 15% of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis.[3] It can be difficult to determine whether disease manifestations are directly caused by the rheumatoid process itself, or from side effects of the medications commonly used to treat it - for example, lung fibrosis from methotrexate, or osteoporosis from corticosteroids. Joints The arthritis of rheumatoid arthritis is due to synovitis, which is inflammation of the synovial membrane that covers the joint. Joints become red, swollen, tender and warm, and stiffness prevents their use. By definition, RA affects multiple joints (it is a polyarthritis). Most commonly, small joints of the hands, feet and cervical spine are affected, but larger joints like the shoulder and knee can also be involved, differing per individual. Eventually, synovitis leads to erosion of the joint surface, causing deformity and loss of function.[1] Inflammation in the joints manifests itself as a soft, "doughy" swelling, causing pain and tenderness to palpation and movement, a sensation of localised warmth, and restricted movement. Increased stiffness upon waking is often a prominent feature and may last for more than an hour. These signs help distinguish rheumatoid from non-inflammatory diseases of the joints such as osteoarthritis (sometimes referred to as the "wear-and-tear" of the joints). In RA, the joints are usually affected in a fairly symmetrical fashion although the initial presentation may be asymmetrical. Hands affected by RA As the pathology progresses the inflammatory activity leads to erosion and destruction of the joint surface, which impairs their range of movement and leads to deformity. The fingers are typically deviated towards the little finger (ulnar deviation) and can assume unnatural shapes. Common deformities in rheumatoid arthritis are the Boutonniere deformity (Hyperflexion at the proximal interphalangeal joint with hyperextension at the distal interphalangeal joint), swan neck deformity (Hyperextension at the proximal interphalangeal joint, hyperflexion at the distal interphalangeal joint). The thumb may develop a "Z-Thumb" deformity with fixed flexion and subluxation at the metacarpophalangeal joint, and hyperextension at the IP joint. Skin The rheumatoid nodule is the cutaneous (strictly speaking subcutaneous) feature most characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. The initial pathologic process in nodule formation is unknown but is thought to be related to small-vessel inflammation. The mature lesion(a part of an organ or tissue which has been damaged) is defined by an area of central necrosis surrounded by palisading macrophages and fibroblasts and a cuff of cellular connective tissue and chronic inflammatory cells. The typical rheumatoid nodule may be a few millimetres to a few centimetres in diameter and is usually found over bony prominences, such as the olecranon, the calcaneal tuberosity, the metacarpophalangeal joints, or other areas that sustain repeated mechanical stress. Nodules are associated with a positive RF titer and severe erosive arthritis. Rarely, they can occur in internal organs. Several forms of vasculitis are also cutaneous manifestations associated with rheumatoid arthritis. A benign form occurs as microinfarcts around the nailfolds. More severe forms include livedo reticularis, which is a network (reticulum) of erythematous to purplish discoloration of the skin due to the presence of an obliterative cutaneous capillaropathy. (This rash is also otherwise associated with the antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome, a hypercoagulable state linked to antiphospholipid antibodies and characterized by recurrent vascular thrombosis and second trimester miscarriages.) Other, rather rare, skin associated symtoms include: pyoderma gangrenosum, a necrotizing, ulcerative, noninfectious neutrophilic dermatosis. Sweet's syndrome, a neutrophilic dermatosis usually associated with myeloproliferative disorders drug reactions erythema nodosum lobular panniculitis atrophy of digital skin palmar erythema diffuse thinning (rice paper skin), and skin fragility (often worsened by corticosteroid use). Lungs Fibrosis of the lungs is a recognised response to rheumatoid disease. It is also a rare but well recognised consequence of therapy (for example with methotrexate and leflunomide). Caplan's syndrome describes lung nodules in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and additional exposure to coal dust. Pleural effusions are also associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Kidneys Renal amyloidosis can occur as a consequence of chronic inflammation. [4] Rheumatoid vasculitis is a rare cause of glomerular disease in the kidney. Treatment with Penicillamine and gold salts are recognized causes of membranous nephropathy. Heart and blood vessels Possible complications that may arise include: pericarditis, endocarditis, left ventricular failure, valvulitis and fibrosis. The risk of cardiovascular, specifically myocardial infarction (heart attack) or congestive heart failure are greater in individuals with RA. Over 1/3 of deaths of people with RA are directly attributable to cardiovascular death. Other Ocular Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes), scleritis, episcleritis and scleromalacia. Gastrointestinal and Hematological Felty syndrome, anemia Neurological Peripheral neuropathy and mononeuritis multiplex may occur. The most common problem is carpal tunnel syndrome due to compression of the median nerve by swelling around the wrist. Atlanto-axial subluxation can occur, owing to erosion of the odontoid process and or/transverse ligaments in the cervical spine's connection to the skull. Such an erosion (>3mm) can give rise to vertebrae slipping over one another and compressing the spinal cord. Clumisiness is initially experienced, but without due care this can progress to quadriplegia. Vasculitis Vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis is common. It typically presents as vasculitic nailfold infarcts. Osteoporosis Osteoporosis classically occurs in RA around inflamed joints. It is postulated to be partially caused by inflammatory cytokines. Lymphoma The incidence of lymphoma is increased in RA as it is in most autoimmune conditions. Diagnosis X-rays X-rays of the hands and feet are generally performed in people with a polyarthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, these may not show any changes in the early stages of the disease, but in more advanced cases demonstrates erosions and bone resorption. X-rays of other joints may be taken if symptoms of pain or swelling occur in those joints.[citation needed] Blood tests When RA is being clinically suspected, immunological studies are required, such as rheumatoid factor (RF, a specific antibody).[5] A negative RF does not rule out RA; rather, the arthritis is called seronegative. During the first year of illness, rheumatoid factor is frequently negative. 80% of individuals eventually convert to seropositive status. RF is also seen in other illnesses, like Sjögren's syndrome, and in approximately 10% of the healthy population, therefore the test is not very specific. Because of this low specificity, a new serological test has been developed in recent years, which tests for the presence of so called anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA). Like RF, this test can detect approximately 80% of all RA cases, but is rarely positive if RA is not present, giving it a specificity of around 98%. In addition, ACP antibodies sometimes can be detected in early stages of the disease, or even before onset of clinical disease. Currently, the most common test for ACP antibodies is the anti-CCP (cyclic citrullinated peptide) test. [6] Also, several other blood tests are usually done to allow for other causes of arthritis, such as lupus erythematosus. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein,[7] full blood count, renal function, liver enzymes and other immunological tests (e.g. antinuclear antibody/ANA)[8] are all performed at this stage. Elevated ferritin levels can reveal hemochromatosis, a mimic RA, or be a sign of Still's disease a seronegative, usually juvenile, variant of rheumatoid. Diagnostic criteria The American College of Rheumatology has defined (1987) the following criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis:[9] Morning stiffness of >1 hour most mornings for at least 6 weeks. Arthritis and soft-tissue swelling of >3 of 14 joints/joint groups, present for at least 6 weeks Arthritis of hand joints, present for at least 6 weeks Symmetric arthritis, present for at least 6 weeks Subcutaneous nodules in specific places Rheumatoid factor at a level above the 95th percentile Radiological changes suggestive of joint erosion At least four criteria have to be met for classification as RA. It is important to note that these criteria are not intended for the diagnosis for routine clinical care. They were primarily intended to categorize research. For example: one of the criteria is the presence of bone erosion on X-Ray. Prevention of bone erosion is one of the main aims of treatment because it is generally irreversible. To wait until all of the ACR criteria for rheumatoid arthritis are met may sometimes result in a worse outcome. Most sufferers and rheumatologists would agree that it would be better to treat the condition as early as possible and prevent bone erosion from occurring, even if this means treating people who don't fulfill the ACR criteria. The ACR criteria are, however, very useful for categorising established rheumatoid arthritis, for example for epidemiological purposes. Differential diagnosis Several other medical conditions can resemble RA, and usually need to be distinguished from it at the time of diagnosis:[10] Crystal induced arthritis (gout, and pseudogout) - usually involves particular joints and can be distinguished with aspiration of joint fluid if in doubt Osteoarthritis - distinguished with X-rays of the affected joints and blood tests Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) - distinguished by specific clinical symptoms and blood tests (antibodies against double-stranded DNA) One of the several types of psoriatic arthritis resembles RA - nail changes and skin symptoms distinguish between them Lyme disease causes erosive arthritis and may closely resemble RA - it may be distinguished by blood test in endemic areas Reactive arthritis (previously Reiter's disease) - asymmetrically involves heel, sacroiliac joints, and large joints of the leg. It is usually associated with urethritis, conjunctivitis, iritis, painless buccal ulcers, and keratoderma blennorrhagica. Ankylosing spondylitis - this involves the spine and is usually diagnosed in males, although a RA-like symmetrical small-joint polyarthritis may occur in the context of this condition. Rarer causes that usually behave differently but may cause joint pains:[10] Sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and Whipple's disease can also resemble RA. Hemochromatosis may cause hand joint arthritis. Acute rheumatic fever can be differentiated from RA by a migratory pattern of joint involvement and evidence of antecedent streptococcal infection. Bacterial arthritis (such as streptococcus) is usually asymmetric, while RA usually involves both sides of the body symmetrically. Gonococcal arthritis (another bacterial arthritis) is also initially migratory and can involve tendons around the wrists and ankles. Pathophysiology Joint abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis Rheumatoid arthritis is an auotimmune disease, the cause for which is still unknown. It is a systemic (whole body) disorder principally affecting synovial joints. Chemical mediators (Cytokines) give rise to inflammation of joint synovium. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, loss of appetite and weight loss are also due to cytokines released in to the blood stream. Blood vessel inflammation (vasculitis) affecting many other organ systems can give rise to systemic complications. [11] As with most autoimmune disease, it is important to distinguish between the cause(s) that trigger the inflammatory process, and those that permit it to persist and progress. It has long been suspected that certain infections could be triggers for this disease. The "mistaken identity" theory suggests that an infection triggers an immune response, leaving behind antibodies that should be specific to that organism. The antibodies are not sufficiently specific, though, and set off an immune attack against part of the host. Because the normal host molecule "looks like" a molecule on the offending organism that triggered the initial immune reaction - this phenomenon is called molecular mimicry. Some infectious organisms suspected of triggering rheumatoid arthritis include Mycoplasma, Erysipelothrix, parvovirus B19 and rubella, but these associations have never been supported in epidemiological studies. Nor has convincing evidence been presented for other types of triggers such as food allergies. There is also no clear evidence that physical and emotional effects, stress and improper diet could be a trigger for the disease. The many negative findings suggest that either the trigger varies, or that it might in fact be a chance event, as suggested by Edwards et al [12]. Epidemiological studies have confirmed a potential association between RA and two herpesvirus infections: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Human Herpes Virus 6 (HHV-6). [13] Individuals with RA are more likely to exhibit an abnormal immune response to the Epstein-Barr virus. [14] [15] The allele HLA-DRB1*0404 is associated with low frequencies of T cells specific for the EBV glycoprotein 110 and predisposes one to develop RA. [16] The factors that allow the inflammation, once initiated, to become permanent and chronic, are much more clearly understood. The genetic association with HLA-DR4 is believed to play a major role in this, as well as the newly discovered associations with the gene PTPN22 and with two additional genes [17], all involved in regulating immune responses. It has also become clear from recent studies that these genetic factors may interact with the most clearly defined environmental risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis, namely cigarette smoking [18] Other environmental factors also appear to modulate the risk of acquiring RA, and hormonal factors in the individual may explain some features of the disease, such as the higher occurrence in women, the not-infrequent onset after child-birth, and the (slight) modulation of disease risk by hormonal medications. Autoimmune diseases require that the affected individual have a defect in the ability to distinguish foreign molecules from the body's own. There are markers on many cells that confer this self-identifying feature. However, some classes of markers allow for RA to happen. 90% of individuals with RA have the cluster of markers known as the HLA-DR4/DR1 cluster, whereas only 40% of unaffected controls do. Thus, in theory, RA requires susceptibility to the disease through genetic endowment with specific markers and an infectious event that triggers an autoimmune response. Once triggered, B lymphocytes produce immunoglobins, and rheumatoid factors of the IgG and IgM classes that are deposited in the tissue, this subsequently leads to the activation of the serum complement cascade and the recruitment of the phagocytic arm of the immune response, which further exacerbates the inflammation of the synovium, leading to edema, vasodilation and infiltration by activated T-cells (mainly CD4 in nodular aggregates and CD8 in diffuse infiltrates). Early and intermediate molecular mediators of inflammation include tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukins IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-15, transforming growth factor beta, fibroblast growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor. Synovial macrophages and dendritic cells further function as antigen presenting cells by expressing MHC class II molecules, leading to an established local immune reaction in the tissue. The disease progresses in concert with formation of granulation tissue at the edges of the synovial lining (pannus) with extensive angiogenesis and production of enzymes that cause tissue damage. Modern pharmacological treatments of RA target these mediators. Once the inflammatory reaction is established, the synovium thickens, the cartilage and the underlying bone begins to disintegrate and evidence of joint destruction accrues. Treatment There is no known cure for rheumatoid arthritis. However, many different types of treatment can be used to alleviate symptoms and/or to modify the disease process. The goal of treatment in this chronic disease must be two-fold: to alleviate the current symptoms, and to prevent the future destruction of the joints and resulting handicap if the disease is left unchecked. These two goals may not always coincide: while pain relievers may achieve the first goal, they do not have any impact on the long-term consequences. For these reasons, most authorities believe that most RA should be treated by at least one specific anti-rheumatic medication, also named DMARD (see below), to which other medications and non-medical interventions can be added as needed. Cortisone therapy has offered relief in the past, but its long-term effects have been deemed undesirable.[19]. However, cortisone injections can be valuable adjuncts to a long-term treatment plan, and using low dosages of daily cortisone (e.g., prednisone or prednisolone, 5-7.5 mg daily) can also have an important benefit if added to a proper specific anti-rheumatic treatment. Pharmacological treatment of RA can be divided into disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), anti-inflammatory agents and analgesics.[20][21] DMARDs have been found to produce durable remissions and delay or halt disease progression. In particular they prevent bone and joint damage from occurring secondary to the uncontrolled inflammation. This is important as such damage is usually irreversible. Anti-inflammatories and analgesics improve pain and stiffness but do not prevent joint damage or slow the disease progression. There is an increasing recognition amongst rheumatologists that permanent damage to the joints occurs at a very early stage in the disease. In the past the strategy used was to start with just an anti-inflammatory drug, and assess progression clinically and using X-rays. If there was evidence that joint damage was starting to occur then a more potent DMARD would be prescribed. Tools such as ultrasound and MRI are more sensitive methods of imaging the joints and have demonstrated that joint damage occurs much earlier and in more sufferers than was previously thought. People with normal X-rays will often have erosions detectable by ultrasound that X ray could not demonstrate. There may be other reasons why starting DMARDs early is beneficial as well as prevention of structural joint damage. In the early stage of the disease, the joints are increasingly infiltrated by cells of the immune system that signal to one another and are thought to set up self-perpetuating chronic inflammation. Interrupting this process as early as possible with an effective DMARD (such as methotrexate) appears to improve the outcome from the RA for years afterwards. Delaying therapy for as little as a few months after the onset of symptoms can result in worse outcomes in the long term. There is therefore considerable interest in establishing the most effective therapy with early arthritis, when they are most responsive to therapy and have the most to gain.[22] Treatment also includes rest and physical activity. Regular exercise is important for maintaining joint mobility and making the joint muscles stronger. Swimming is especially good, as it allows for exercise with a minimum of stress on the joints. Heat and cold applications are modalities that can ease symptoms before and after exercise. Pain in the joints is sometimes alleviated by oral acetaminophen (paracetamol). Other areas of the body, such as the eyes and lining of the heart, are treated individually. However, there is no diet that has been shown to alleviate rheumatoid arthritis, although fish oil may have anti-inflammatory effects. Disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) The term Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Agent was originally introduced to indicate a drug that reduced evidence of processes thought to underly the disease, such as a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, reduced haemoglobin level, raised rheumatoid factor level and more recently, raised C-reactive protein level. More recently, the term has been used to indicate a drug that reduces the rate of damage to bone and cartilage. DMARDs can be further subdivided into traditional small molecular mass drugs synthesised chemically and newer 'biological' agents produced through genetic engineering. Traditional small molecular mass drugs: azathioprine ciclosporin (cyclosporine A) D-penicillamine gold salts hydroxychloroquine leflunomide methotrexate (MTX) minocycline sulfasalazine (SSZ) Cytotoxic drugs: Cyclophosphamide The most important and most common adverse events relate to liver and bone marrow toxicity (MTX, SSZ, leflunomide, azathioprine, gold compounds, D-penicillamine), renal toxicity (cyclosporine A, parenteral gold salts, D-penicillamine), pneumonitis (MTX), allergic skin reactions (gold compounds, SSZ), autoimmunity (D-penicillamine, SSZ, minocycline) and infections (azathioprine, cyclosporine A). Hydroxychloroquine may cause ocular toxicity, although this is rare, and because hydroxychloroquine does not affect the bone marrow or liver it is often considered to be the DMARD with the least toxicity. Unfortunately hydroxychloroquine is not very potent, and is usually insufficient to control symptoms on its own. Many rheumatologists consider methotrexate to be the most important and useful DMARD, largely because of lower rates of stopping the drug through toxicity. Nevertheless, methotrexate is often considered as a very "toxic" drug. This reputation is not entirely justified, and at times can result in people being denied the most effective treatment for their arthritis. Although methotrexate does indeed have the potential to suppress the bone marrow or cause hepatitis, these effects can be monitored using regular blood tests, and the drug withdrawn at an early stage if the tests are abnormal, before any serious harm is done (typically the blood tests return to normal after stopping the drug). In clinical trials, where one of a range of different DMARDs where used, people who were prescribed methotrexate were those who stayed on their medication the longest (the others stopped theirs because of either side-effects or failure of the drug to control the arthritis). Methotrexate is often preferred by rheumatologists because if it does not control arthritis on its own then it works well in combination with many other drugs, especially the biological agents. Other DMARDs may not be as effective or safe in combination with biological agents. Biological agents Biological agents (biologics include: tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) blockers - etanercept (Embrel), infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira) Interleukin 1 blockers - anakinra monoclonal antibodies against B cells - rituximab (Rituxan)[23] T cell activation blocker abatacept (Orencia) Anti-inflammatory agents and analgesics Anti-inflammatory agents include: glucocorticoids Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs, most also act as analgesics) Analgesics include: acetaminophen (Paracetamol outside US) opiates diproqualone lidocaine topical The Prosorba column blood filtering device was approved by the FDA for treatment of RA in 1999 [24] However, the results have been very modest. Historic treatments for RA have also included: RICE, acupuncture, apple diet, nutmeg, some light exercise every now and then, nettles, bee venom, copper bracelets, rhubarb diet, rest, extractions of teeth, fasting, honey, vitamins, insulin, magnets, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[25]. Most of these have either had no effect at all, or their effects have been modest and transient, while not being generalizable. Other therapies Other therapies are weight loss, occupational therapy, podiatry, physiotherapy, joint injections, and special tools to improve hard movements (e.g. special tin-openers). Severely affected joints may require joint replacement surgery, such as knee replacement. Medicine formularies Plan or option Link to appropriate Mediscor formulary GMHPP Gold Options G1000, G500 and G200 Blue Options B300 and B200 GMISHPP Blue Option B100 [Core] n/a Epidemiology The incidence of RA is in the region of 3 cases per 10,000 population per annum. Onset is uncommon under the age of 15 and from then on the incidence rises with age until the age of 80. The prevalence rate is 1%, with women affected three to five times as often as men. It is 4 times more common in smokers than non-smokers. Some Native American groups have higher prevalence rates (5-6%) and black persons from the Caribbean region have lower prevalence rates. First-degree relatives prevalence rate is 2-3% and disease genetic concordance in monozygotic twins is approximately 15-20%. It is strongly associated with the inherited tissue type Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen HLA-DR4 (most specifically DR0401 and 0404) — hence family history is an important risk factor. Rheumatoid arthritis affects women three times more often than men, and it can first develop at any age. The risk of first developing the disease (the disease incidence) appears to be greatest for women between 40 and 50 years of age, and for men somewhat later.[29] RA is a chronic disease, and although rarely, a spontaneous remission may occur, the natural course is almost invariably one of persistent symptoms, waxing and waning in intensity, and a progressive deterioration of joint structures leading to deformations and disability. Prognosis The course of the disease varies greatly. Some people have mild short-term symptoms, but in most the disease is progressive for life. Around 20%-30% will have subcutaneous nodules (known as rheumatoid nodules); this is associated with a poor prognosis. Disability Daily living activities are impaired in most individuals. After 5 years of disease, approximately 33% of sufferers will not be working After 10 years, approximately half will have substantial functional disability. Prognostic factors Poor prognostic factors include persistent synovitis, early erosive disease, extra-articular findings (including subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules), positive serum RF findings, positive serum antiCCP autoantibodies, carriership of HLA-DR4 "Shared Epitope" alleles, family history of RA, poor functional status, socioeconomic factors, elevated acute phase response (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP]), and increased clinical severity. Mortality Estimates of the life-shortening effect of RA vary; most sources cite a lifespan reduction of 5 to 10 years. According to the UK's National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society, "Young age at onset, long disease duration, the concurrent presence of other health problems (called co-morbidity), and characteristics of severe RA – such as poor functional ability or overall health status, a lot of joint damage on x-rays, the need for hospitalisation or involvement of organs other than the joints – have been shown to associate with higher mortality".[26] Positive responses to treatment may indicate a better prognosis. A 2005 study by the Mayo Clinic noted that RA sufferers suffer a doubled risk of heart disease,[27] independent of other risk factors such as diabetes, alcohol abuse, and elevated cholesterol, blood pressure and body mass index. The mechanism by which RA causes this increased risk remains unknown; the presence of chronic inflammation has been proposed as a contributing factor.[28] References 1. abc 2. ab Majithia V, Geraci SA (2007). "Rheumatoid arthritis: diagnosis and management". Am. J. Med. 120 (11): 936–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.005. PMID 17976416. Landré-Beauvais AJ (1800). La goutte asthénique primitive (doctoral thesis). reproduced in Landré-Beauvais AJ (March 2001). "The first description of rheumatoid arthritis. Unabridged text of the doctoral dissertation presented in 1800". Joint Bone Spine 68 (2): 130–43. PMID 11324929. 3. Turesson C, O'Fallon WM, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL (2003). "Extraarticular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 years". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62 (8): 722–7. doi:10.1136/ard.62.8.722. PMID 12860726. 4. de Groot K. "[Renal manifestations in rheumatic diseases]". Internist (Berl) 2007 Aug;48(8):779-85. PMID 17571244. 5. Rheumatoid Factor. Lab Tests Online. American Association for Clinical Chemistry (September 30, 2006). Retrieved on 2006-10-28. 6. CCP (Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide antibody). Lab Tests Online. American Association for Clinical Chemistry (January 15, 2005). Retrieved on 2006-10-28. 7. C-Reactive Protein. Lab Tests Online. American Association for Clinical Chemistry (September 3, 2004). Retrieved on 2006-10-28. 8. ANA (Antinuclear Antibody). Lab Tests Online. American Association for Clinical Chemistry (December 13, 2004). Retrieved on 2006-10-28. 9. Arnett F, Edworthy S, Bloch D, McShane D, Fries J, Cooper N, Healey L, Kaplan S, Liang M, Luthra H (1988). "The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis.". Arthritis Rheum 31 (3): 315-24. doi:10.1002/art.1780310302. PMID 3358796. 10. a b (1992) in Berkow R: The Merck Manual, 16th, Merck Publishing Group, 1307-08. ISBN 0-91191-016-6. 11. Choy EHS, Panayi GS (2001). "Cytokine pathways and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis.". N Engl J Med 344: 907–916. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103223441207. 12. Edwards JC, Cambridge G, Abrahams VM. Do self-perpetuating B lymphocytes drive human autoimmune disease? Immunology. 1999;97:188-96. 13. R Álvarez-Lafuente , B Fernández-Gutiérrez , S de Miguel , J A Jover , R Rollin , E Loza , D Clemente , J R Lamas. "Potential relationship between herpes viruses and rheumatoid arthritis: analysis with quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2005;64:1357-1359. 14. P B Ferrell, C T Aitcheson, G R Pearson, and E M Tan. "Seroepidemiological study of relationships between Epstein-Barr virus and rheumatoid arthritis". J Clin Invest 1981 March; 67(3): 681–687. Full text at PMC: 370617 15. Michael A. Catalano, Dennis A. Carson, Susan F. Slovin, Douglas D. Richman, and John H. Vaughan. "Antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus-determined antigens in normal subjects and in patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 76, No. 11, pp. 5825-5828, November 1979 Immunology. 16. Nathalie Balandraud, Jean Roudier. "Epstein–Barr virus and rheumatoid arthritis". Autoimmunity Reviews Volume 3, Issue 5, July 2004, Pages 362-367. 17. Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L et al. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis--a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1199-209. 18. Padyukov L, Silva C, Stolt P, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L. A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3085-92. 19. NIH: Results of Long-Continued Cortisone Administration in Rheumatoid Arthritis 20. O'Dell J (2004). "Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis.". N Engl J Med 350 (25): 2591-602. doi:10.1056/NEJMra040226. PMID 15201416. 21. Hasler P (Jun 2006). "Biological therapies directed against cells in autoimmune disease.". Springer Semin Immunopathol 27 (4): 443-56. doi:10.1007/s00281-006-0013-8. PMID 16738955. 22. Vital E, Emery P (Sep 15 2005). "Advances in the treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis.". Am Fam Physician 72 (6): 1002, 1004. PMID 16190499. 23. Edwards J, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close D, Stevens R, Shaw T (2004). "Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.". N Engl J Med 350 (25): 2572-81. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032534. PMID 15201414. 24. Fresenius HemoCare, Inc., "New Hope for Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients," press release, September 17, 1999. 25. NIH: History of the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis 26. Excess mortality in rheumatoid arthritis 27. The second largest contributor of mortality is cerebrovascular disease. Increased risk of heart disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients 28. Cardiac disease in rheumatoid arthritis 29. Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA (2006). "Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: a systematic review". Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 36 (3): 182–8. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.006. PMID 17045630. 30. http://mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/research/renotes/rn-05txt.htm Tennessee Origins of Rheumatoid Arthritis 31. http://www.arc.org.uk/newsviews/arctdy/104/bones.htm Bones of Contention 32. Rothschild BM, Rothschild C, Helbling M (2003). "Unified theory of the origins of erosive arthritis: conditioning as a protective/directing mechanism?". J. Rheumatol. 30 (10): 2095–102. PMID 14528501. 33. Scientist finds surprising links between arthritis and tuberculosis 34. Appelboom T, de Boelpaepe C, Ehrlich GE, Famaey JP (1981). "Rubens and the question of antiquity of rheumatoid arthritis". JAMA 245 (5): 483–6. doi:10.1001/jama.245.5.483. PMID 7005475. 35. http://japan.medscape.com/viewarticle/538251 Did RA travel from New World to Old? The Rubens connection 36. Dequeker J., Rico H. (1992). "Rheumatoid arthritis-like deformities in an early 16thcentury painting of the Flemish-Dutch school". JAMA 268: 249-251. doi:10.1001/jama.268.2.249. PMID 1608144. 37. Garrod AB (1859). The Nature and Treatment of Gout and Rheumatic Gout. London: Walton and Maberly. 38. "The Insider: Amgen recruits high-flier to help Enbrel sales take off", Seattle PostIntelligencer, 2007-11-07. Retrieved on 2003-03-24. 39. "Sopranos" Star Aida Turturro Brings Rheumatoid Arthritis Awareness Campaign to Philadelphia. Retrieved on 2007-12-18.