Notes for Tutors 08-09 - University of Warwick

advertisement

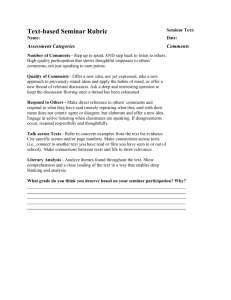

Modes of Reading (2008-2009): A Guide for Tutors MJ Kooy 22.9.08 Pedagogical Aims First of all, what is Modes about? As I see it, Modes of Reading is trying to do three things: 1. De-mythologizing English studies. Modes seeks to get rid of a number of bad myths attached to the process of reading and interpreting literary texts. Here are a few: - Interpretation is about finding the right answer. No it’s not. There are competing answers, and some are more right than others, but there is no single right interpretation. Many first time students of English, especially those fresh from A-level, approach literary culture as if texts were secret codes, offering clues to secret meanings, and that it’s the job of the expert reader (ie, someone on an English degree) to uncover them. This is a very simplistic view of the way meanings are constructed by authors or determined by readers. - Reading is ‘innocent’. As novice readers, we tend to think that we are neutral observers of literary culture. No we’re not. Interpreters occupy a position in relation to literature that is determined by a host of contingent factors: our culture, political commitments, religion, history, nation, temperament, and so on. These limit our work as readers, as well as being the condition of its possibility. - Literature speaks for itself. In a sense, the more complex a literary text is, the less this is true of it. Literature is a cultural phenomenon – texts have historical origins, and a history of reception. They are flashpoints of political, religious and moral conflict. Literary texts participate in discourses that are larger than themselves, even if they are often themselves original contributors to those discourses (now that’s a paradox worth interrogating). - Doing English is a question of temperament. Oscar Wilde thought so. Maybe he was right. But English Studies is now a discipline. It has a history that is culturally specific and it is bounded by institutionally encoded norms and practices, and economic exigencies. Disputes about these norms are themselves part of the discipline. One of the interesting features of literary study today is that – in contrast to disciplines like history and art – it is generally reluctant to own up to its disciplinary constraints. - The ‘English’ of English Studies is a neutral term. Is it indeed? 2. Naturalising Theoretical Reflection. As you can see, de-mythologizing means isn’t just a negation of something; it’s also about setting out certain positive (complex) features of literary studies. These features have historically been the subject of reflection, a body of knowledge that is sometimes today called by the convenient shorthand ‘Theory’. And this brings us to the second of the pedagogical aims of Modes of Reading: to introduce students to a selected range of theoretical reflection upon cultural interpretation as such, and English studies more particularly. Hence the readings from people like Raymond Williams, Freud, Edward Said, and so on. To most students such theory texts appear to be not only difficult, but secondary to the act of reading literature as such. Some treat theory with a take it or leave it attitude. A very important part of Modes is to reverse this: to help students see theoretical reflection as a necessary part of textual analysis, in other words, to naturalise theoretical reflection. We would like to enable students to become readers who are awake theoretically. We’ve not been able to find an anthology that gives students the historical range and conceptual variety we think is needed for this task, so the Department has devised its own, in the shape of the Reading Theory Pack. Part of this aspect of the module is also covered by the important series of optional lectures offered by Prof. Docherty, which are specifically focused on twentieth-century theoretical reflections on culture and the literary. 3. Reading Primary Texts. You can’t talk about literature at a theoretical level without having texts to talk about, too. So Modes also introduces students to a range of primary texts. We don’t take an instrumentalist view of the texts, though. That is, in Modes of Reading we don’t treat the literary text as a stable entity to which we can then apply various theoretical approaches in our search of a single meaning that sticks (that would take us back to one of the myths I mentioned above). True, interpretation is contingent on extra-textual factors, some of them beyond our control (and perhaps even our cognisance), but that does not free us from the task of reading attentively. Literature speaks, even though the meaning of words is not transparent. So, we offer students primary texts as a site where they can work as interpreters, and then reflect upon that process of interpretation. A few further points about what to expect: Expect discomfort. Please remember (and if you don’t, it will become painfully obvious soon) that your cohort will be made up of mostly smart, but sometimes quite fragile students fresh out of school trying to come to grips with a radically different model of teaching/learning. While they are realising that they are expected to work on their own, think critically, discuss what they think without being stigmatised as nerds, we are introducing to them critical/theoretical texts for the first time in their lives. Try to imagine what is going through their heads – the language is unfamiliar, so is the method of argument, what is the objective of this exercise? How am I supposed to score marks in this? What do you mean I am supposed to talk about this in front of other people? What is the use of all this? Panic! Over the years we have found that one way to deal with their (quite legitimate) anxieties is to emphasize, misquoting Raymond Williams, that theory is ordinary. That is, it is a systematized process of reflecting on the ordinary and regular act of reflection itself, the act we perform everyday in our material cultural lives (shopping, reading, talking, watching TV, listening to music, voting, working etc). Therefore, in introducing them to theory texts, our objective is to give them a sample of the range or modes of reflection available. We are asking them to assess and engage with these reflective processes. We do not expect them to show familiarity with ‘isms’. We do not expect them to argue (at this stage) that one ‘ism’ has a monopoly on objective truth. We do not expect them to spout technical terms. We do expect them to argue about the contours of the arguments in front them. We do expect them to realise that they will encounter these positions in the various interpretations of all the literary texts they will engage with during their time in the university. We do expect them to become familiar with using theory and concepts in their own academic writing. Thinking about thinking can be an uncomfortable experience. It is important to let them know that this discomfort is OK, in fact, it may be one of the central experiences of engaging with theory. We can suddenly find our own automatic assumptions analysed, challenged and exposed. But this enables to better understand, change and/or defend our convictions and decisions – in academic life and outside it. Lecturers on Modes don’t necessarily agree with one another. Students will hear different points of view. There will be inconsistencies, even disagreements, in the course of the year. Lecturers may offer different readings of the same texts; and they will certainly give different emphases to some of the key aspects of studying literature and literary cultures today: the importance of political, religious and ethical perspectives; the importance of gender and sexual orientation; the importance of history and nation; and so on. This doesn’t make it easy for students, or tutors for that matter. Part of the content of the module, and not just a side-effect of the manner of its delivery, is this dissonance. Students should get accustomed to literary studies as a site of live debates. Tutors have a large degree of autonomy. We provide the syllabus and the set texts, and the lecturers offer students a great deal of additional material by way of interpretation and clarification. But seminar tutors are asked to put their own stamp on the seminars. For instance, you may supplement the set reading with texts chosen by yourself and you may shuffle things around as it suits you. You may ask students to make short presentations, or set mini-assignments, and so on. Find out what others do, and don’t be shy about stealing someone else’s good practice. Do make sure that you allow some time in the seminars to discuss the lectures, as students may want to ask for clarification on some points. It’s a good idea to attend the Thursday lectures yourself, to know where your students are at. Some Checklists: Before Your first Seminar - Buy the primary texts and the Theory Reading Pack, familiarise yourself with the syllabus - Confirm with the dept office the time and place of your seminar(s) - Check that you have a copy of the seminar class list: all students have been assigned to a group - You might want to draw up your own Module information for your specific seminar, tailored to your own needs (I highly recommend this) – Eg, if your seminar meets on Tuesday, i.e., before the Thursday lecture, you may want to have the seminar topics occur one week later (eg, if the week 2 Thursday lecture is on ‘Howl’, you may want to take this as the subject for your week 3 Tuesday seminar – in which case you’ll need to come up with something else for your seminar to talk about in week 2.) - It’s good to bring photocopies of your tailored schedule for the seminar to your week 1 meeting. You should have been given a code so you can use the office photocopier – if you haven’t, then get in touch with the office directly. Your first seminar This is a chance to get introduce yourself to the group and also the members of the group to each other. It’s also the time to do some very important pedagogical work: to give the students a clear indication of what the module is about (and what’s expected of the students); and to send out a clear message about what your own personal expectations are – in other words, to set the tone. One thing I like to stress when talking to first year students for the first time is that here at university students, not their teachers, are responsible for their own learning – we as staff are only responsible for giving them the tools. And one of the most important tools we give them is the safe haven of a seminar where they can express and experiment with ideas. You can expect students to be of quite a high calibre, but nonetheless uncertain on their feet. Most first-year students crave the high regard of their tutor and their peers, but don’t yet know what’s required to achieve this: some will be very shy, others very verbose. The best thing you can do is react not so much to the overt behaviour as to the impulse behind it, by reassuring students of your goodwill. Be clear about what you expect, and build a positive, relaxed and always supportive atmosphere for expressing opinions and ideas. Once you’ve set that tone, most students will find themselves up to the challenges that you’ll be giving them. Here are some things to remember to touch on during the first seminar: - Attendance: the department is very strict about attendance, so make sure you keep accurate records. There are penalties for absences, and you should make these clear to the students (see the Undergraduate Student Handbook). The first week of term is traditionally a bit chaotic, and there will almost certainly be floating students without assigned classes, or ones who show up who are not on your list. Don’t worry – they will eventually be slotted in. Please let the office know of any withdrawals/transfers/other amendments to your list. - Assessment: there are assessed and unassessed essays due – you should explain what’s involved, and when they’re due. There’s a heavy penalty for missed unassessed work – do pass on this information (see the module homepage). - Do some work on the Week 1 assignment If you have any questions about this or other matters, just get in touch with me, or bring them with you to our first meeting. Here is some further information for things that crop up in the course of the year. Assessment Term 1: Two non-assessed essays of approx. 2,000 words, set and marked by the tutors. Nature and topic is up to you, the object is to pick up on and help any problems, so what is important is rapid feedback. You may want to get both the pieces of work in by end of week 8, so you should be marked and returned to the students before the party season and vacation takes over. This way, the students will get some feedback before their first assessed essay. Terms 2 and 3: Assessed essays of approx. 3,500 words (each comprising 50 per cent of the final course) are required. Titles are centrally set; essays marked by tutors. Some tutors provide additional titles for their own groups to supplement the centrally-set titles. Any request for extension must be made by the student to the department’s Director of Undergraduate studies, not to the tutor. We do not read or comment or drafts of the essays, but the students should be welcomed to discuss ideas with you during your office hours. Plagiarism The essays for Modes will be among the first university-level writing exercises demanded of students. Some will plagiarise from internet sources, perhaps maliciously, perhaps out of ignorance of good citation practice. It’s part of our job to instruct students in this area: to help them identify (and eliminate) bad practice in their own work, and to show them how to use and cite sources properly. It’s especially important that we send out the clear message that plagiarism is unacceptable under all circumstances. Pastoral Points: 1. If you encounter a student with personal problems drop a note to the personal tutor immediately. 2. If a student is struggling with the writing of essays please refer them to the Royal Literary Fund Fellows, who are usually to be found in Room 421. 3. First Year Review takes place at the end of Term 1. You will be asked to write brief reports on all your students. 4. There’s a Modes of Reading file in the office. You will find copies of previous assessed essay titles, which may be useful. 5. I will assign mentors to those part-time tutors who are new to the course. Routine questions about teaching and marking should be addressed to the mentors, but of course I am happy to advise on any specific difficulties. Marking The essays are marked out of 100 (see the appropriate section in the current Undergraduate Student Handbook). The pass mark is 40%. Please return the essays as soon as you have marked them to the office and keep a record of your marks. After you have marked both the assessed essays, you simply add up to the two marks and divided by two, ‘rounding up’ where necessary. The students submit two copies of the assessed essays. One is a ‘marked’ copy, where the tutors mark, annotate and comment. This copy is returned to the students along with the pink cover sheet. The ‘unmarked’/’clean’ copy should be returned to the English Department Office with the white cover sheet. Essays should be marked and returned within three weeks after the deadline for submission. It’s worth bearing in mind that First Year marks do not count towards the student’s final degree, they just need to pass. Don’t agonise too much about whether to give them a 61 or a 62. First year essays are not normally second-marked, but any fail mark should be passed on to the convenor. Many thanks and good luck!