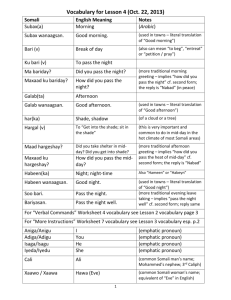

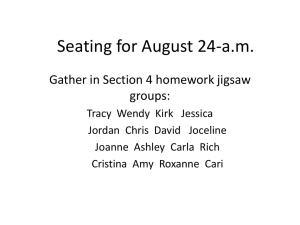

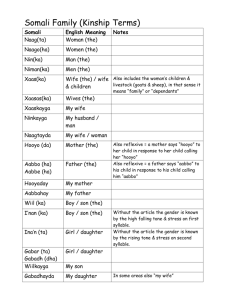

Research on Somali Communities

advertisement