Developing alternative communication strategies to facilitate

advertisement

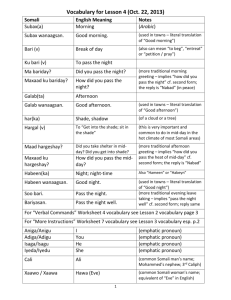

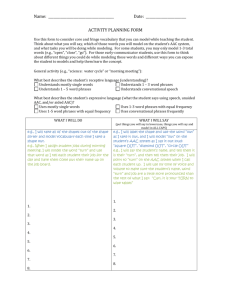

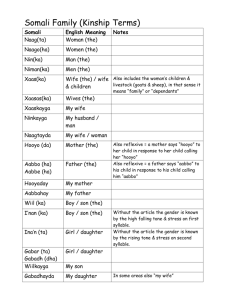

ESRC Seminar 6 Abstract June 2006 Developing alternative communication strategies to facilitate communication with Somali refugees in primary care Authors: Marianne Johnson1, Zeinab Mohamed2, Gareth Evans2 School of Nursing1, School of Informatics2, The University of Manchester Background: Significant numbers of Somali refugees and asylum seekers are still entering the UK as a result of the continuing war in Somalia (Home Office, 2005). Somali refugees tend to have very limited English and literacy skills as a result of poor educational opportunities; consequently they experience communication difficulties during healthcare consultations (Harris, 2004). Although communication is deemed the single most important factor influencing the success of a consultation (Hornberger et al., 1996; Fazil et al., 2002), many gaps and inadequacies pervade the provision of language services for non-English speaking patients. Most studies investigating language barriers still tend to recommend using professional interpreters, link workers or Language Line (Gerrish, 2004, Rhodes & Nocon, 2003) but no standardised alternative communication strategy exists in primary care when these services are unavailable (Johnson, 2004). Alternative communication strategy: This proof-of-principle study aimed to develop and evaluate an alternative communication strategy to address this gap. This strategy involves using a computer system containing pictographic symbols, bilingual text labels and recorded Somali speech. It is designed as a tool to help Englishspeaking clinicians elicit information from Somali patients with limited English and literacy. A live demonstration of how the system works will be given during the poster presentation. Evaluating this strategy: The success of the system was evaluated in simulated asthma reviews with clinicians and Somali volunteers with asthma (Doss et al., 1991; Dyches et al., 2002; Fried-Oken, Howard & Stewart, 1991). Preliminary findings indicate that the communication aid enabled history taking between clinicians and Somalis. A list of recommendations for improving the system for possible future deployment within primary care is being compiled as a result of this proof-ofprinciple study. References Doss LS, Locke P, Johnston S, Reichle J, Sigafoos J, Charpentier P, Foster D. Initial comparison of the efficiency of a variety of AAC systems for ordering meals in fast food restaurants. AAC, 1991, 7: 256-265. Dyches TT, Davis A, Lucido BR, Young JR. Generalization of skills using pictographic and voice output communication devices. AAC, 2002, 18: 124-131. Fried-Oken M, Howard JM, Stewart SR. Feedback on AAC intervention from adults who are temporarily unable to speak. AAC, 1991, 7: 43-50. Gerrish K, Chau R, Sobowale A, & Birks E. Bridging the language barrier: the use of interpreters in primary care nursing. Health and Social Care in the Community, 2004, 12(5): 407-413. ESRC Seminar 6 Abstract June 2006 Harris H. The Somali Community in the UK: What we know and how we know it. King’s College London, 2004. Home Office. Home Office Asylum Statistics, 2nd Quarter, United Kingdom. 2005. [Website]. Available from: <http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/asylumq205.pdf> [Accessed September 2005]. Johnson MJ. What can we learn from drawing parallels between people who use AAC and people whose first language is not English? Communication Matters, 2004, 18(2): 15-17. Rhodes P, & Nocon A. A problem of communication? Diabetes care among Bangladeshi people in Bradford. Health and Social Care in the Community, 2003, 11(1): 45-54.