Zero Waste, Landfill Diversion at UC Santa Barbara

advertisement

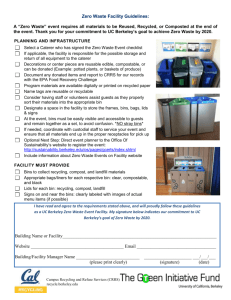

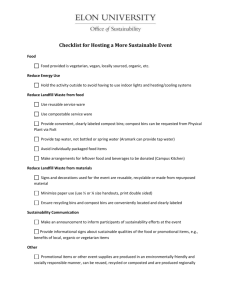

Zero Waste 1 Zero Waste Landfill Diversion at UC Santa Barbara Stephen M.D. Read Writing 2LK Dr. LeeAnne Kryder November 7th, 2013 Zero Waste 2 Abstract Upgrades to waste receptacles provide significant improvements in landfill diversion and contribute to UC Santa Barbara’s goal of zero waste by 2020. Improved signage can help guide the flow of waste into the proper bins. A few simple modifications can solve several problems with “Big Bertha” bin sets without the need for complete replacement, and the new BigBelly solar compactors reduce trash volume by a factor of 4. A transition to compostable bags in restrooms can keep hundreds of pounds of paper towels out of landfills every week. All of these affordable, relatively simple measures will help reduce UCSB’s contribution to landfills. Zero Waste Landfill Diversion at UC Santa Barbara Zero Waste 3 Introduction “[Our] Dining Commons alone produce four tons of compost in a single week.” -Katie Maynard Sustainability Coordinator, UCSB Geography Department October 22nd, 2013 “With a student body of over 21,000, UCSB’s production and treatment of waste is an extremely significant and highly relevant issue” (Parnell-Wolfe, 2013, UCSB Sustainability Website). Truer words were never spoken. Efforts to reduce waste production and increase diversion from landfills are crucial to reducing the negative environmental impact of our University. In the next decade, UCSB has the opportunity to blaze the trail of sustainable waste management, and lead the way for universities across the country. Large-scale measures such as the transition to tray-less dining can bring UCSB close to its goal of zero waste by 2020. However, the final few percentage points may prove elusive. The best way to capture them may well be the waste bins themselves. By maintaining consistent, clearly-marked sets of waste bins on campus, UCSB can improve its waste management in two valuable ways: by enabling the recycling and composting habits of waste-conscious individuals, and by creating these habits in others. What is Zero Waste? The University of California holds a system-wide goal of zero waste by the year 2020, as defined on page 4 of the University of California Policy on Sustainable Practices for 2013: For the purposes of measuring compliance with UC’s zero waste goal, locations need to meet or exceed 95% diversion of municipal solid waste. Ultimately, UC’s zero waste goal strives for the elimination of all materials sent to the landfill by 2020. According to the 2012 UC Santa Barbara Waste Diversion Plan, UCSB also intends to meet the requirements specified in the Zero Waste International Alliance’s “peer-reviewed zero waste definition,” adopted on August 12th, 2009: Zero Waste is a goal that is ethical, economical, efficient and visionary, to guide people in changing their lifestyles and practices to emulate sustainable natural cycles, where all discarded materials are designed to become resources for others to use. Zero Waste 4 Zero Waste means designing and managing products and processes to systematically avoid and eliminate the volume and toxicity of waste and materials, conserve and recover all resources, and not burn or bury them. Implementing Zero Waste will eliminate all discharges to land, water or air that are a threat to planetary, human, animal or plant health. More information on the background of this definition and the Zero Waste International Alliance can be found on their website, which is listed in the “References” section. An Apple a Day Every Tuesday and Thursday, I stop at Carrillo Dining Commons for lunch before heading off to class. On the way out, I grab an organic granny smith apple. As I cruise the bike paths, one hand holds my bike steady, the other holds the apple. By the time I lock up my bike outside Lotte Lehmann Concert Hall, only the core remains. I look around for somewhere to put it, but there isn’t a compost bin in sight. With class starting in a few minutes, I don’t have time to ride to the University Center to find one. Being from San Francisco, I was raised with the three-bin system. Paper, cardboard, cans, and bottles go in the blue bin. The green bin is for dirty napkins and bits of uneaten food. The black bin, the traditional “trash can”, is used only when absolutely necessary. For me, it feels no less wrong to put an apple core in a trash can than it does to put a plastic bag in a compost bin. Not everyone is familiar with composting and recycling. I spent the first few weeks of college picking plastic bottles and scraps of cardboard out of the trash bin in my dorm room. For whatever reason, my roommate refused to recycle. After about a month of coaching, he has it all figured out. It is quite rewarding to know that I have passed my waste-conscious habits to another person. Imagine that my roommate takes an apple from the same basket, rides his bike to the same bike rack, and looks around for a trash can to toss away the core. He encounters three bins, clearly labeled as “Compost”, “Recycle”, and “Landfill.” As my roommate reaches toward the bin marked “Landfill”, he hesitates. The sign on the “Compost” bin shows food scraps, including an apple core similar to the one in his hand. Even without me there to coach him, the apple core ends up in the correct bin. What’s Your Sign? In addition to the fact that compost and recycling bins are difficult to find on campus, I have encountered several issues with their labeling. At my high school, students from the environmental studies classes signed up for one-hour shifts to stand in the cafeteria guiding the endless stream of waste into the appropriate bins. While somewhat effective, this system was inconvenient and thus short-lived. We soon transitioned to a clear, understandable set of signs, similar to those pictured in Figure 1. Zero Waste 5 The University Center (UCEN) is one of the few locations on campus that is widely known to have compost bins. According to Katie Maynard, the Sustainability Coordinator for UCSB’s Geology Department, “all restaurants that sign-on under the new contract are required to use compostable dishware.” That means everything from the Panda Express bowl to the Root 217 fork can be composted. However, all of that effort will go to waste with signage blunders like the one pictured in Figure 2, below. Figure 1. Signs that are clear, consistent, and easy to understand are an important to making proper waste disposal effortless. Source: UCSF Sustainability Website. “All restaurants that sign-on under the new contract are required to use compostable dishware.” -Katie Maynard Sustainability Coordinator, UCSB Geography Department October 22nd, 2013 Above the bin in the center, labeled Figure 2. The signs above these bins are switched; they direct “cans, bottles, and other trash” into the bin labeled “Compostable.” Source: Stephen M.D. Read. “Compostable,” hangs a sign that reads “Cans, Bottles and other Trash Here -- Zero Waste 6 Landfill.” The signs above the unlabeled black bins read “root 217, Panda, Wahoo’s Trash Here - Compostable.” Clearly the UCEN is putting measures in place to divert waste from landfills. In this case, however, it isn’t “just the thought that counts.” Even the most waste-conscious individuals will be stumped by this set of bins. Promoting correct waste-sorting habits is difficult to begin with, so there is no room for careless mistakes like this. There is no magic bullet to solve the problem of landfill diversion, but one thing is certain: clear, concise, and consistent signage is a very important piece of the puzzle. “Big Berthas” The older sets of bins on campus, called “Big Berthas”, are particularly confusing. The set pictured in Figure 3 is a prime example of this. On the leftmost bin, the label simply reads “Newspaper”. Beyond the fact that it does not include a compost bin, this set appears to have no place for paper or cardboard. In reality, nearly all paper products are recyclable, and can be placed in the same bin. It may only take moment to figure this out, but the confusing signage is can be enough to frustrate would-be recyclers into sending their scratch paper to the landfill. Figure 3. This “Big Bertha” set has not yet been modified, and lacks proper signage. Figure 4. The clear labeling on this “Big Bertha” set makes trash-sorting simple. The good news is, Source: UCSB Geography Department Website the “Big Berthas” do not need to be replaced entirely. With a bit of retooling, they can be upgraded to improve their clarity. Figure 4 shows a modified set of “Big Bertha” bins, with improved signage. The right bin remains as a trash can, the only change is the use of the term “Landfill.” This is not insignificant, as it makes people more conscious of the final destination of items placed in this bin. The left three bins are combined into two, called “Office Pack” and “Recyclables”. The blue bin is for “co-mingled recyclables”, a term that includes all common paper, plastic, glass, and aluminum products. The remaining bin is converted to hold compostable materials. The items that belong in each bin are listed on the appropriate sign, with prominent visual aids. This simple but effective retrofit serves a dual purpose: it adds a compost bin and improves ease-of-use. Source: UCSB Geography Department Website BigBelly Waste Compactors Zero Waste 7 I conducted a brief interview with Tim Witwer, an intern at Housing and Residential Services, about recycling and composting at UC Santa Barbara. “Mark [Rousseau] is my boss, he’s the Energy and Sustainability Manager,” Mr. Witwer told me, “He does a lot of work making things run more efficiently.” When I asked Tim if there were any recent upgrades to UCSB’s waste-management system, he was eager to talk about the BigBelly solar-powered waste compactors (see Figure 5) that have recently been installed in several locations on campus. “They started with one... it was actually a student’s idea,” Mr. Witwer said, “It worked so well that they started phasing them in at all of the Dining Commons.” Figure 5. A few years from now, these solar-powered, secure, and well-labeled BigBelly sets may be the only bins on campus. Figure 6. Elan Franz brought BigBelly compactors to UCSB during his freshman year. Source: UCSB Geography Department Website Source: Stephen M.D. Read The new BigBelly compactors were brought to campus by a Mechanical Engineering major named Elan Franz (see Figure 6), “whose first course assignment as a freshman was to ‘think of a way to improve something, write about it, and then present on it’” (“Big Berthas”, 2012, UCSB Geography Department Website). By the time of Elan Franz’s graduation in 2012, BigBelly compactors had gained support among administrators in the Facilities Management, Residential Services, and Geography Departments. Zero Waste 8 Elan Franz articulated the many benefits of BigBelly compactors quite well, as quoted in the November 6th, 2012 article, “Conversion of Big Berthas to BigBellies is Big Business”: The project has been wildly successful. Instead of taking out the trash at food service stations twice a day, grounds workers are now only servicing them twice a week. This opens up opportunities to give attention to other areas of campus maintenance that are in need. In the old trashcans, if a raccoon was found, animal services was called to euthanize the animal. Now the pests are kept out of the trash permanently and relocate themselves. The amount of loose clutter on campus has been reduced as the trashcans lock the contents in and the amount of recyclable items that accidentally get thrown in the trash has been significantly reduced just based on the appearance of these bins. The ultimate goal is to convert the entire campus to BigBelly. This way, densified trash enters the dumpsters causing them to fill up less often. The garbage trucks then no longer have to drive the 32 miles to the landfill as often, saving potentially hundreds of tons of carbon emissions each year. (Para. 5) It is inspiring to see that what started as a first-year student’s class project has turned into a popular and successful improvement to UCSB’s waste management system. As funding for BigBelly systems on campus increases, the full extent of this system’s value will be realized. Compostable Bags A vast majority of the waste deposited in restroom trash cans is damp paper towels. This material is excellent for compost. Unfortunately, more often than not, it ends up in a landfill. A simple method to divert this waste is to use compostable bags. At all of San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department facilities, restrooms are fitted with signs requesting that the public only deposit paper towels in the trash cans. Sorting is not necessary, as the plant-based bags are deposited directly in the compost bin when full. The biggest barrier to this improvement is cost. Relative to traditional plastic bags, plantbased compostable bags are very expensive. According to Katie Maynard, about “$35,000 a year is the price difference between the two.” As with the BigBelly compactors, the only thing preventing a substantial upgrade to UC Santa Barbara’s waste management system is a lack of funding. Conclusion Zero Waste 9 “With landfills reaching their capacity and the numerous negative environmental impacts associated with landfills... reducing, reusing, recycling, and composting our waste is of the utmost importance.” -2012 UC Santa Barbara Waste Diversion Plan The quote above is from the first paragraph of the 2012 UC Santa Barbara Waste Diversion Plan. UC Santa Barbara is well on its way to zero waste by 2020, but there is still much work to be done to reach that goal. In the 2012 fiscal year, UCSB “achieved an overall waste diversion rate of 69.73%” (Waste Diversion Plan, p.6). This was a “7.67% increase from the pervious year’s 62.00% diversion rate” (Waste Diversion Plan, p.31). Certainly this improvement is in part due to the addition of several BigBelly compactors, improved signage, and a slight reduction in total waste production. While it may seem that a majority of waste diversion occurs behind-the-scenes, individuals can have a significant impact. Elan Franz is an excellent example of a single student taking initiative and bringing positive change to our campus. That being said, such a large dedication of time and effort, while admirable, is not always necessary for students, faculty, and staff to contribute to waste diversion. The process of improving signage is currently underway, and many of the “Big Bertha” sets have been modified to include compost bins. Yet, as the misplaced signs above the University Center bins demonstrate, the process is not yet complete. There are still inconsistencies, and some confusion as a result. As a member of the University of California Santa Barbara community, take it upon yourself to help reach the goal of zero waste by 2020. Though the bins may be difficult to find, and the signage confusing, take a minute to make sure your waste goes to the right place.