Benenson, Group structure and gender final version1

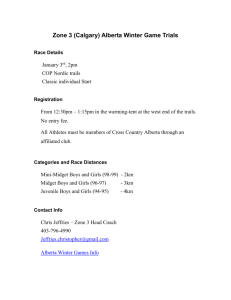

advertisement

1 EVIDENCE THAT CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS HAVE INTERNAL MODELS OF PEER INTERACTIONS THAT ARE GENDER DIFFERENTIATED Henry Markovits Université du Québec à Montréal Joyce Benenson Eva Dolenszky McGill University Article accepted for publication in Child Development, June, 2000. 2 ABSTRACT This study examined whether children’s internal representations reflect gender differences that have been found in peer interactions. The dimensions examined were (a) preferences for dyadic or group situations, (b) whether children who are friends with a given target child will be likely to be friends with each other, and (c) perceptions of the probability of knowing information about friends. Participants from preschool, grades 2, 6, 8, 10 and college were asked questions about both typical girls and boys. Results indicate that both girls and boys (a) rate typical boys as preferring group interactions more than typical girls, a difference present as early as preschool, (b) rate typical boys as having a higher probability of being friends with one another if they are friends with the same target boy, and (c) rate typical girls as having a greater probability of knowing certain types of information about friends. These results are consistent with the existence of internal models of social interactions that are at least partially gender specific. 3 INTRODUCTION There is a growing body of evidence that children and adults construct representational models of social interactions that encode patterns of behavior (for a review, see Baldwin, 1992). Such models translate regularities in behavior into cognitive structures that in turn guide the way that social information is processed. One major example is attachment theory which postulates the existence of an internal “working model” of the attachment relation that represents patterns of responsiveness of a child’s care-giver (e.g. Bowlby, 1969; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). More recently, researchers have begun to examine internal models of peer relations. For example, Burks, Dodge, Price, & Laird, (1999) have found that aggressive children interpret social stimuli in ways that appear to be related to their underlying representational models of peers. Similarly, Markovits and Dumas (1999) have found that children develop rules that mirror the transitive structure of friendship relations. In the research on adults, Von Hecker (1997) has proposed that adults construct mental models (Johnson-Laird, 1983) of social situations that allow them to represent some basic elements of the structure of such interactions. The idea that individuals possess representations of social interactions that allow them to make inferences related to the organization of social situations is a particularly interesting one. Ethologists have in fact often argued that understanding social interactions requires a multileveled approach that includes knowledge of the relationships between individuals as well as of specific behaviors (Hinde, 1976). If children are able to translate the structural regularities of social interactions into representations, then their internal models should reflect the structure of their peer experiences. One such important structural dimension concerns gender. Children’s peer interactions are segregated by gender (for a review, see Maccoby, 1988), and there are differences in the organization of social activities between girls and boys that appear early in 4 development. First, studies have shown that boys prefer interacting in groups compared to girls (Benenson, 1990; Benenson, 1993; Ladd, 1983; Savin-Williams, 1979, 1980), a difference that appears by the end of preschool (Benenson, Apostoleris, & Parnass, 1997). Second, studies have shown that boys’ friendships are more interconnected than are girls’ friendships (Benenson, 1990; Benenson, et al., 1997; Parker & Seal, 1996; Savin-Williams, 1979, 1980). That is, this implies that friends of a given child are more likely to be friends themselves amongst boys than amongst girls. Third, girls’ friendships have been found to be more intimate than boys’ friendships (Buhrmester and Prager, 1995; Lever, 1978). This implies that girls would be expected to know more about their friends than boys. Diaz & Berndt (1982) found that elementary school girls knew more about concrete characteristics of their best friends, (e.g. their birthdays) than did boys, although there were no differences in knowledge about personal preferences or personality characteristics. This study examined whether children’s internal representations reflect these three aspects of peer interactions. The basic method that we used involved presenting schematic descriptions of peer interactions that depicted either ‘typical’ girls or ‘typical’ boys without referring to any real children, to eliminate making judgments made by accessing cues related to a participant’s knowledge of specific children. Further, to reduce the possibility that children might be using conscious representations of gender-appropriate behavior, participants were not asked to make explicit comparisons between girls and boys. Instead, they were asked to make judgments about girls and boys separately, and differences in the nature of representations were inferred by comparing these judgments. To test the dyad-group distinction, we constructed cartoons of children either sitting/talking or playing with a ball, in either dyads or groups of four. These situations were chosen in order to provide a more concrete basis for children’s choices, to reflect 5 gender preferences for activities with greater or lesser verbal and physical involvement, and to naturally allow for both dyadic and group involvement. To test the degree of interconnectedness between a typical girl’s or boy’s friends, we asked children to rate how likely it would be that a target’s friends would be friends with each other. Finally, to examine differences in knowledge about friends, we asked children to rate the probability that a typical boy or girl would know six different items of information about his or her same-sex friend. Finally, we examined a large range of ages between preschool and college. Behavioral observation has shown that some of the distinctions looked at here appear to be established towards the end of preschool (Benenson, Apostoleris, & Parnass, 1997). Since internal models require experience for their construction (Baldwin, 1992), we would expect a developmental lag compared to behavior. Thus we would expect a clear increase in the extent to which internal models reflect behavior between preschool and the later primary school ages. We also expected that representations about the type of information that friends know of each other, which refer to a more abstract dimension than the behavioral differences looked at here, would develop later on. We also included samples of younger and older adolescents, primarily in order to examine whether the basic models developed over the primary school period continue to be found at these later ages. METHOD Participants A total of 287 children attending one of several schools in the Montreal area participated in this study. Of these, 38 were in preschool (19 girls, 19 boys; average age: 5 years, 1 month; range: 4 years, 2 months to 6 years), 33 were in grade 2 (17 girls, 16 boys; average age: 8 years, 2 months; range: 7 years 2 months to 9 years 3 months), 26 were in grade 6 (12 girls, 14 boys; 6 average age: 12 years, 1 month; range: 11 years 1 month to 13 years 2 months), 59 were in grade 8 (26 girls, 33 boys; average age: 14 years, 1 month; range: 13 years 1 month to 15 years 4 months), 45 were in grade 10 (23 girls, 22 boys; average age: 16 years; range: 15 years 2 months to 17 years), and 77 were in a junior college, which will be referred to as grade 13 for ease of reference (37 girls, 40 boys; average age: 19 years, 4 months; range: 17 years 7 months to 22 years 7 months). Participants primarily came from mixed European backgrounds and were from middle to lower-middle class neighborhoods. Materials Four versions of a paper-and-pencil questionnaire were constructed. Versions 1 and 2 presented questions about a target girl first followed by questions about a target boy. Versions 3 and 4 presented questions about a target boy first followed by questions about a target girl. The front page of each questionnaire had a picture of a boy or a girl sitting on a bench at the bottom of the page. At the top of the page were the following general instructions: “The purpose of this study is to understand how children think about social situations. Imagine that the child below is your age and is a typical girl/boy. I am going to ask you some questions about this girl/boy in the following pages. The girl/boy is always drawn in dark gray as shown below.” Following this, participants were asked to indicate their age, sex, and grade. The following describe the measures administered for one version of the questionnaire. Group-dyad rating task. The next page of the questionnaire showed pictures of four social situations in which the target girl (shown on the first page) is interacting with other girls. In order, these were four girls playing ball, two girls talking, four girls talking, and two girls playing ball. Beside each picture was the question: “How much would a typical girl enjoy being in this situation”. Underneath the question was a six-point scale with the following points: 1 (not 7 at all), 2 (a little bit), 3 (sort of), 4 (pretty much), 5 (quite a lot), 6 (a lot). Group-dyad paired comparisons. On the next two pages, were 6 pairs of situations in which the target girl was depicted. Under each of the two situations, there was a box, and the following instruction: “Check the box next to the situation the girl likes best”. The six comparisons were, in order: (1) Two girls playing ball vs Four girls talking; (2) Four girls playing ball vs Two girls talking; (3) Four girls talking vs Four girls playing ball; (4) Two girls talking vs Two girls playing ball; (5) Two girls playing ball vs Four girls playing ball; (6) Four girls talking vs Two girls talking. Information task. On the top of the following page, the instructions read: “Here is a picture of two girls who are best friends. How likely is it that they know the following things about each other?” Underneath this was a picture of two girls talking on a bench. Following this was a list of six items. Under each item was the following scale: 1 (not at all likely), 2 (a little likely), 3 (sort of likely), 4 (pretty likely), 5 (quite likely), 6 (very likely). Some items were varied according to grade level, in order to make them more appropriate. For participants at the elementary school level, the items used were: (1) Their birthdays, (2) The names of their sisters and brothers, (3) Their favorite sports, (4) Their favorite TV shows, (5) The names of each other’s friends at school, (6) Whether they get good or bad marks in class. For high school participants, these items were the same except for the fifth item which was replaced by: (5) Whether they have a girlfriend or not. Items used for college participants were the same as elementary school except for the forth and fifth items which were replaced by: (4) Their favorite movie actors, (5) Whether they have a serious relationship with their girlfriends. Items (1), (2), (5) and (6) refer to concrete information about the friend’s life, while items (3) and (4) refer to personal preferences. 8 Friends of friends task. On the top of the next page were the following instructions: “Here is a picture of the girl in gray with three other girls. The girl in gray is friends with each of the three other girls. How likely is it that the three other girls are friends with each other?”. Underneath this was a scale with the following points: 1 (not at all likely), 2 ( a little likely), 3 (sort of likely), 4 (pretty likely), 5 (quite likely), 6 (very likely). Underneath the scale was a picture of the target girl sitting with three other girls (all the girls appear to be looking at an outside stimulus). Following this final question, all measures were repeated in the same order except that they now referred to a target boy instead of a girl. A second version of the same questionnaire was identical to the one described, except that the order of the items used in the rating task, the dyadic comparison task and the scaling task respectively, were inverted within each task. Finally, the other two versions of these questionnaires were identical to the two previously described except that the tasks examining boys were given initially, followed by the tasks examining girls. Pictures used to illustrate situations were made from identical templates for both boy and girl targets, in order to ensure that there were no observable differences in portrayed interactions. Procedure For the high school and college participants, questionnaires were distributed to entire classes. For the elementary groups, questionnaires were given out to entire classes, and an experimenter explained each task in sequence to the class. Preschool children were interviewed individually. Pretesting indicated that preschoolers did not understand the information task and the friends of friends task, so they were only given the first two tasks. RESULTS Paired comparisons 9 For the four comparisons that compared dyads versus groups, we calculated the number of times that groups were preferred to dyads. Table 1 shows the mean scores for girls and boys by grade (see Table 1). An ANOVA using the mean number of group choices for target girls and for target boys as dependent variables with Gender of target child considered as a repeated measure and Grade and Gender of participant as independent variables was performed. This showed significant main effects of Grade, F(1, 266) = 6.33, p < .001 and of Target gender, F(1, 266) = 118.77, p < .001. There was a significant interaction between Target gender and Participant gender, F(1, 266) = 3.89, p < .05. Inspection of Table 1 shows that the number of group choices was significantly higher for target boys than for target girls across all grade levels. Girls generally predicted a greater difference in group preference between target boys and girls than did boys. Post hoc analyses of the main effect of Grade indicated that the difference between target boys and girls was significantly greater between preschoolers and between grades 10 and 13, respectively. Finally, for each grade level, we determined whether the mean number of group choices was significantly different from 2 (which indicates either random choice or a lack of preference), using the Wilcoxon nonparametric procedure (see Table 1). These indicate that at all grade levels between grades 2 and 13, boys are clearly considered to prefer group situations, both by girls and by boys. Rating task Table 2 indicates mean ratings for target boys and girls for each of the four situations depicted (see Table 2). We first looked at ratings concerning target boys. A repeated measures ANOVA with Activity (sitting or playing) and Number of children (dyad or group) as the repeated factors and Grade and Gender of participants as independent variables was performed. This indicated significant main effects for Grade, F(5, 266) = 28.19, p < .001, Activity, F(1, 266) 10 = 72.05, p < .001 and Number of children, F(1, 266) = 99.59, p < .001. There were significant interactions between Activity and Grade, F(5, 266) = 4.29, p < .01, between Activity and Number of children, F(1, 266) = 6.14, p < .05, and between Activity, Number of children, Grade and Gender of participant, F(5, 266) = 2.69, p < .05. All post hoc comparisons here and subsequently used simple effects tests. Children rated target boys as preferring the play situation to the sitting situation at grade 6, F(1, 266) = 17.91, p < .01, at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 51.88, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 90.06, p < .01, and at grade 13, F(1, 266) = 69.01, p < .01. Target boys were considered to prefer groups over dyads across activities at preschool, F(1, 266) = 17.27, p < .01, at grade 2, F(1, 266) = 14.46, p < .01, at grade 6, F(1, 266) = 7.15, p < .01, at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 90.91, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 73.64, p < .01, and at grade 13, F(1, 266) = 80.91, p < .01. We then looked at ratings given for target girls. A repeated measures ANOVA with Activity (sitting or playing) and Number of children (dyad or group) as repeated factors and Grade and Gender of participants as independent variables was performed. This showed significant main effects of Activity, F(1, 266) = 98.81, p < .001, Grade, F(5, 266) = 4.19, p < .01, and Gender, F(1, 266) = 7.15, p < .01. In addition there were significant interactions between Activity and Grade, F(5, 266) = 8.05, p < .001, between Activity and Gender, F(1, 266) = 4.41, p < .05, between Number of children, Grade and Gender, F(5, 266) = 3.20, p < .01, and between Activity, Number of children, Grade and Gender, F(5, 266) = 3.16, p < .01. There was a marginally significant effect of Number of children, F(1, 266) = 3.26, p < .07, which indicated a trend towards preferring dyads over groups. Target girls were seen as preferring the situation of sitting over that of playing at grade 2, F(1, 266) = 4.03, p < .05, at grade 6, F(1, 266) = 5.90, p < .05, at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 126.94, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 67.12, p < .01, and at grade 11 13, F(1, 266) = 185.84, p < .01. In addition, there was a gender difference in how activities were rated. While both girls and boys rated sitting equally highly overall, girls rating playing more highly than did boys, F(1, 266) = 12.64, p < .01. Information task Table 3 indicates the mean ratings for each of the six items of information presented to participants, by grade and gender (see Table 3). Individual analyses for each of the six items were first performed using mean ratings for target girls and target boys with Gender of target child as a repeated measure and Grade and Gender of participant as independent variables. For a friend’s birthday, there was a significant main effect of Gender of target, F(1, 230) = 144.68, p < .001 and a significant interaction between Gender of target and Grade, F(4, 230) = 8.82, p < .001. Target girls were judged to have a higher probability of knowing a friend’s birthday than target boys at grade 6, F(1, 230) = 8.26, p < .01, at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 97.96, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 67.35, p < .01, and at grade 13, F(1, 266) = 68.37, p < .01. For the names of a friend’s siblings, there was a significant main effect of Gender of target, F(1, 230) = 78.02, p < .001 and significant interactions between Gender of target and Grade, F(4, 230) = 3.73, p < .01 and between Gender of target and Gender of participant, F(1, 230) = 5.45, p < .02. Target girls were judged to have a higher probability of knowing names of a friend’s siblings than target boys at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 39.93, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 42.10, p < .01, and at grade 13, F(1, 266) = 35.53, p < .01. For a friend’s marks at school, there was a significant main effect of Gender of target, F(1, 230) = 46.97, p < .001 and a significant interaction between Gender of target and Grade, F(4, 230) = 8.93, p < .001. Target girls were judged to have a higher probability of knowing a friend’s marks than target boys at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 26.31, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 37.51, p < .01, and at grade 13, F(1, 266) = 49.22, p < .01. For friends or 12 serious relationships, there was a significant main effect of Gender of target, F(1, 230) = 77.24, p < .001 and a significant interaction between Gender of target and Gender of participant, F(4, 230) = 4.47, p < .05. Overall target girls were judged to have a higher probability of knowing about friends or relationships than target boys. Analysis of the interaction did not reveal any specific significant differences. For a friend’s favorite TV show/actor, there was a significant effect of Grade, F(4, 230) = 2.47, p < .05 and a significant interaction between Gender of target and Grade, F(4, 230) = 12.35, p < .001. Post hoc analyses indicated that target girls were judged to have a higher probability of knowing this information at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 8.35, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 5.03, p < .05, and at grade 13, F(1, 266) = 45.22, p < .01. Target boys were judged to have a higher probability at grade 6, F(1, 266) = 8.38, p < .01. Finally, for favorite sports, there was a significant effect of Gender of target, F(1, 230) = 80.97, p < .001. Target boys were judged to have a higher probability of knowing a friend’s favorite sport than target girls. We then grouped together the four items concerning concrete characteristics - birthdays, names of siblings, school performance and friends/relationships. An Anova with mean ratings for target boys and girls as the dependent variables, with Gender of target as a repeated measure, and Grade and Gender of participants as independent variables was then performed. This indicated a significant effect of Gender of target, F(1, 230) = 200.66, p < .001 and significant interactions between Gender of target and Grade, F(4, 230) = 7.12, p < .001, and between Gender of target and Gender of participants, F(1,230) = 6.48, p < .02. Target girls were judged to have a higher probability of knowing this information than target boys at grade 6, F(1, 230) = 14.24, p < .01, at grade 8, F(1, 266) = 89.96, p < .01, at grade 10, F(1, 266) = 90.11, p < .01, and at grade 13, F(1, 266) = 109.71, p < .01. Analysis of the interaction involving Gender of participants showed that target girls’ probability of knowing this kind of information was rated higher by girls than by 13 boys (5.55 to 5.41), while target boys’ probability of knowing this information was rated higher by boys than by girls (4.61 to 4.45). This latter result did not affect the overall pattern. Friends of friends task Table 4 shows the mean ratings of the probability that friends of a target child will be friends with each other as a function of grade and gender, for target girls and boys (see Table 4). An Anova with ratings for target girls and boys with repeated measure across Gender of target as dependent variable and Grade and Gender of participant as independent variables was performed. This indicated significant main effects of Grade, F(4, 230) = 4.64, p < .01, and Gender of target, F(1, 230) = 39.22, p < .001. Analyses showed that ratings for target boys were higher than ratings for target girls. Combined ratings across gender were higher for grade two children than for all other grades, although this did not affect the difference in ratings between target boys and girls. DISCUSSION The results of this study show that internal representations of peer interactions are at least partially gender specific. Particularly striking is the strong agreement between boys’ and girls’ representations, showing that while girls and boys might interact in segregated contexts, they are able to encode the major differences in behavior that characterize each others’ interactions. In the following discussion, we will focus on the representations of the differences in peer relationships as a function of gender that are shared by both girls and boys. Our results show that both boys and girls have gender differentiated representations of group size preferences. The most striking aspect of these representations is the perception that boys prefer group to dyadic interactions, a perception that exists in an embryonic way in preschool and is well established by the beginning of elementary school. The fact that only two 14 activity types were used may limit the extent to which these results can be generalized. However, it should be noted that the two activity types were specifically chosen to control for gender differences in activity preferences. Boys were perceived to prefer being in groups for both an activity that they were perceived to prefer more (playing ball) and for one that they were perceived to prefer less (sitting/talking). Children at all ages thus appear to have a representation that boys prefer interacting in groups which is not related to perceived preference for a specific kind of activity. Representations of how girls prefer to interact shows a much less clear pattern. Girls are perceived as liking the situation of sitting/talking more than the situation involving playing ball. In neither case, however, is there a clear perception that girls prefer dyadic or group interactions. Thus, it seems fair to conclude that children’s internal models of girls’ interactions do not include a strong generalized preference for either group or dyadic situations. Further research that focuses explicitly on a variety of girls' activities is necessary to determine whether perceptions of girls' preferences for group or dyadic interactions are related to type of activity. Finally, these results do not permit any generalization as to activity preferences amongst girls or boys, since the portrayed activities are not necessarily representative of gender typical ways of interaction. Children’s internal models may be more refined than can be detected in this study, which would require a more detailed examination of a wider range of type of activities. A second dimension that was examined concerned the ways that friendships are structured. Observational data is consistent with the idea that boys tend to form social groups with inter-related friendship structures, while girls tend more towards dyadic friendships who tend not to be friends with one another. The results of the friends of friends task show that as early as grade 2, boys who are friends with a given boy are perceived to have a greater 15 probability of being mutual friends than are girls in a comparable situation. The third dimension concerned access to information about friends. We presented children with a list of four items of information about friends’ concrete characteristics (Diaz & Berndt, 1982). In addition, we gave two items of information that referred to personal preferences. Our results show that by sixth grade, children consistently predicted that girls will have a greater probability of knowing about friends’ birthdays, names of siblings, school performance and friendships than will boys. The developmental pattern for each of the four individual items is remarkably similar. Also in line with results obtained by Diaz & Berndt (1982), ratings concerning preferences were more mixed. In fact, for the item a friend’s ‘favorite sports’, children consistently rate boys’ probability of knowing this as greater than that of girls. Thus, children’s representations of the kinds of knowledge about friends that are likely to be known by boys and girls appears to be quite accurate, although this discrimination is later to appear than gender differences concerning the group-dyad distinction and the probability of friends being friends. These results allow a picture of the developmental course followed by the internal models that we have examined. Firstly, there are some differences in the ages at which the factors that we have looked at here appear to be incorporated into children’s internal models. The perception that boys prefer group interactions is present as early as preschool. Gender differences in the structure of friendships appear as early as grade 2, while differences pertaining to access to information appear in a general sense by grade 6. These results suggest that children develop progressively more refined models of peer interactions, by successively incorporating different and possibly more abstract aspects of these interactions. Our results also show that these distinctions remain relatively constant across 16 adolescence. Clearly, the increasing variety of societal influences that adolescents are subjected to does not appear to have any strong modulating effects on the internal models that we have looked at here. The long-term continuity of the these models is consistent with the idea that while internal representations may be drawn from experience, they are subsequently used to process and interpret subsequent experience (Baldwin, 1992). It is also important to note that what we have examined here does not entail that the participants had explicit knowledge of the observed gender differences. At no time were they asked to make explicit comparisons; rather, we asked participants to make inferences about the social interactions of typical girls and typical boys in a way that made making explicit gender comparisons difficult at best. The effects that we have observed thus reflect differences in the representations of how boys interact compared to representations of how girls interact. The question of whether these differences are consciously accessible to children remains an open one. Finally, it should be noted that the dimensions examined in these studies reflect gender differences in social interactions that are the subject of on-going research. None of these dimensions are easily observable since they refer either to structural aspects of interactions (dyads versus groups, friendship networks) or, as is the case with differences in information about friends, to patterns of knowledge about social partners. This makes the precocity and accuracy with which children make implicit distinctions that correspond to observed gender differences quite remarkable and testifies to the importance of the representational process in understanding social interactions. 17 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a team grant from the Fonds pour la Formation de Chercheurs et l'Aide a la Recherche (FCAR) to the first two authors. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Henry Markovits, Département de psychologie, Université du Québec à Montréal, C.P. 8888, Succ. "A", Montréal, Québec H3C 3P8, Canada or Joyce F. Benenson, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, McGill University, 3700 McTavish Street, Montréal, Québec H3A 1Y2, Canada. The authors would like to thank the reviewers of a previous version of this manuscript for their helpful comments. 18 ADDRESSES AND AFFILIATIONS Henry Markovits Département de psychologie Université du Québec à Montréal C.P. 8888, Succ "A" Montréal, Québec H3C 3P8 e-mail: MARKOVITS.HENRY@UQAM.CA Joyce F. Benenson Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology McGill University 3700 McTavish Street Montréal, Québec H3A 1Y2 Eva Dolenszky McGill University 19 REFERENCES Baldwin, M. W. (1992). Relational schema and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 461-484. Benenson, J. F. (1990). Gender differences in social networks. Journal of Early Adolescence, 10, 472-495. Benenson, J. F. (1993). Greater preference among females than males for dyadic interaction in early childhood. Child Development, 64, 544-555. Benenson, J. F., Apostoleris, N. H., & Parnass, J. (1997). Age and sex differences in dyadic and group interaction. Developmental Psychology, 33, 538-543. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Buhrmester, D. and Prager, K. (1995). Patterns and functions of self-disclosure during childhood and adolescence. In K. J. Rotenberg (Ed.), Disclosure processes in children and adolescents. Cambridge studies in social and emotional development (pp. 10-56). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Burks, V. S., Dodge, K. A., Price, J. M., & Laird, R. D. (1999). Internal representational models of peers: Implications for the development of problematic behavior. Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 802-810. Diaz, R. M. & Berndt, T. J. (1982). Children’s knowledge of a best friend: Fact or Fancy? Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 787-794. Hinde, R. A. (1976). On describing relationships. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 1-19. Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983). Mental Models, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 20 Ladd, G. W. (1983). Social networks of popular, average, and rejected children in school settings. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29, 283-307. Lever, J. (1978). Sex differences in the complexity of children’s play and games. American Sociological Review, 43, 471-483. Maccoby, E. E. (1988). Gender as a social category. Developmental Psychology, 24, 755765. Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to a level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research (pp. 66-104). Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1-2, Serial No. 209). Markovits, H. & Dumas, C. (1999). Developmental patterns in the understanding of social and physical transitivity, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 73, 95-114. Parker, J. G., & Seal, J. (1996). Forming, losing, renewing, and replacing friendships: Applying temporal parameters to the assessment of children's friendship experiences. Child Development, 67, 2248-2268. Savin-Williams, R. C. (1979). Dominance hierarchies in groups of early adolescents. Child Development, 50, 923-935. Savin-Williams, R. C. (1980). Social interactions of adolescent females in natural groups. In H. C. Foot, A. J. Chapman, & J. R. Smith (Eds.), Friendship and social relations in children (pp. 343-364). New York: Wiley. Von Hecker, U. (1997). How do logical inference rules help construct social mental models? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 367-400. 21 Table 1 Mean number of times groups were chosen over dyads in paired comparisons (maximum score = 4). Number of group choices Gender Grade N Target girl Target boy Girls Preschool 19 1.89 (0.88) 2.21 (1.03) 2 17 2.18 (1.07) 3.18* (0.53) 6 12 1.75 (1.35) 3.33* (0.89) 8 26 1.77 (1.03) 3.31* (0.62) 10 23 2.09 (0.85) 3.39* (0.78) 13 37 2.11 (1.10) 3.27* (0.80) Preschool 19 1.89 (1.05) 2.47 (0.96) 2 16 2.13 (1.41) 3.19* (0.83) 6 14 1.93 (1.07) 2.57 (1.09) 8 33 2.76* (1.00) 3.30* (0.77) 10 22 2.41 (1.26) 3.32* (0.78) 13 40 2.15 (1.12) 3.20* (0.53) Boys Note. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. *indicates score significantly different from 2 22 Table 2 Mean ratings of types of interactions for target boys and target girls Type of interaction – target boys Gende Grade N Type of interaction – target girls 2 sitting 4 sitting 2 playing 4 playing 2 sitting 4 sitting 2 playing 4 playing 4.21 (2.34) 4.74 (2.07) 4.05 (2.44) 4.79 (1.96) 4.00 (2.26) 4.63 (1.73) 4.00 (2.31) 3.95 (2.25) 5.06 (1.20) 5.59 (0.79) 5.18 (1.33) 5.24 (1.43) 5.24 (1.30) 4.94 (1.20) 4.94 (1.25) 5.06 (1.20) 4.58 (1.00) 5.17 (0.83) 5.50 (0.67) 5.83 (0.57) 5.75 (0.62) 5.17 (0.71) 5.42 (0.90) 5.00 (0.85) 3.23 (1.24) 4.50 (1.55) 4.27 (0.96) 5.35 (0.84) 5.58 (0.64) 4.89 (1.24) 4.08 (1.32) 3.65 (1.32) 3.17 (0.78) 4.35 (1.07) 4.52 (0.89) 5.52 (0.51) 5.35 (0.12) 4.78 (1.12) 3.87 (1.12) 4.09 (1.12) 3.67 (0.94) 4.49 (1.14) 4.92 (1.08) 5.73 (0.58) 5.51 (1.88) 5.24 (1.16) 4.19 (1.36) 4.03 (1.08) r Girls Preschool 1 9 2 1 7 6 1 2 8 2 6 10 2 3 13 3 7 23 Boys Preschool 1 3.95 (2.01) 5.16 (1.74) 5.32 (1.45) 4.84 (2.03) 4.90 (1.91) 3.68 (2.16) 4.16 (2.34) 4.16 (2.19) 4.69 (1.08) 5.63 (0.61) 5.44 (0.89) 5.88 (0.34) 5.31 (1.20) 5.06 (1.12) 4.38 (1.50) 4.56 (1.51) 4.14 (1.29) 4.43 (1.74) 4.86 (1.29) 5.21 (1.80) 5.14 (1.17) 4.64 (1.55) 4.21 (1.53) 4.07 (1.86) 3.33 (1.31) 3.88 (1.27) 4.00 (1.37) 4.82 (1.16) 4.73 (0.94) 5.30 (1.04) 3.24 (1.32) 3.33 (1.55) 3.23 (1.07) 4.14 (1.08) 4.68 (0.89) 5.41 (0.66) 5.14 (0.84) 5.32 (0.78) 3.68 (1.21) 3.82 (1.40) 4.1 (1.01) 4.93 (0.99) 4.73 (1.01) 5.33 (0.76) 5.22 (0.95) 5.42 (0.84) 3.25 (1.41) 3.43 (1.46) 9 2 1 6 6 1 4 8 3 3 10 2 2 13 4 0 Note. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. 24 Table 3 Mean rating of the probability that target girls and boys will know specific items of information about friends by grade and gender. Type of information about target’s friends Birthday Names of siblings School performance Grade Gender Girls Boys Girls Boys Girls Boys 2 Girls 5.06 (1.60) 4.88 (1.49) 5.00 (1.32) 4.53 (1.59) 4.65 (1.97) 5.00 (1.54) Boys 5.44 (0.96) 5.19 (1.28) 5.19 (1.11) 5.13 (0.72) 4.81 (1.33) 5.12 (1.33) Girls 5.75 (0.45) 4.67 (1.07) 5.58 (0.67) 4.83 (0.72) 5.50 (0.90) 5.42 (0.67) Boys 5.43 (1.09) 4.93 (1.14) 4.86 (1.10) 4.71 (1.14) 5.07 (1.14) 4.43 (1.70) Girls 5.77 (0.51) 3.73 (1.49) 5.89 (0.43) 4.54 (1.53) 5.69 (0.55) 4.23 (1.50) Boys 5.42 (1.03) 3.82 (1.49) 5.33 (0.96) 4.64 (1.22) 4.97 (1.05) 4.64 (1.32) Girls 5.74 (0.69) 4.13 (1.22) 5.91 (0.29) 4.70 (1.02) 5.57 (0.66) 4.17 (1.27) Boys 5.77 (0.43) 3.96 (1.09) 5.64 (0.58) 4.46 (1.14) 5.64 (0.66) 4.59 (1.29) Girls 5.76 (0.80) 4.30 (1.53) 5.60 (0.90) 4.60 (1.28) 5.03 (1.16) 3.89 (1.07) Boys 5.60 (0.71) 4.40 (1.34) 5.63 (0.74) 4.93 (1.27) 5.23 (0.95) 4.23 (1.25) 6 8 10 13 Note. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. 25 Table 3 (continued) Mean rating of the probability that target girls and boys will know specific items of information about friends by grade and gender. Type of information Friendship Sports TV shows/actors Grade Gender Girls Boys Girls Boys Girls Boys 2 Girls 5.06 (1.43) 3.82 (1.85) 4.47 (1.81) 5.35 (1.37) 4.35 (1.90) 4.35 (1.80) Boys 5.38 (0.88) 4.44 (1.50) 4.56 (1.71) 5.94 (0.25) 4.63 (1.09) 5.56 (1.31) Girls 5.75 (0.62) 4.08 (1.44) 4.67 (1.07) 5.92 (0.29) 4.92 (1.16) 5.58 (0.69) Boys 4.79 (1.58) 4.43 (1.45) 4.29 (1.73) 5.93 (0.27) 4.29 (1.68) 5.29 (0.73) Girls 6.00 (0.00) 5.19 (1.02) 4.81 (1.23) 5.50 (0.94) 5.04 (1.15) 4.39 (1.36) Boys 5.64 (0.65) 5.18 (1.07) 4.33 (1.54) 5.09 (1.29) 4.79 (1.24) 4.33 (1.19) Girls 5.65 (0.64) 4.83 (1.64) 5.04 (1.11) 5.70 (0.70) 4.83 (1.27) 4.35 (1.37) Boys 5.86 (0.47) 5.00 (1.27) 5.00 (1.07) 5.55 (0.67) 5.18 (0.73) 4.68 (1.13) Girls 5.60 (0.76) 4.51 (1.19) 4.76 (1.23) 5.60 (0.60) 4.70 (1.20) 3.78 (1.18) Boys 5.53 (0.82) 4.70 (1.24) 4.78 (1.33) 5.35 (0.89) 5.20 (0.82) 3.88 (1.09) 6 8 10 13 Note. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. 26 Table 4 Mean ratings of probability that friends of a target child will be friends. Probability of being friends Grade Gender Target girl Target boy 2 Girls 5.24 (0.97) 5.53 (1.01) Boys 4.50 (1.71) 5.44 (1.31) Girls 4.08 (1.24) 5.42 (0.79) Boys 4.29 (0.99) 4.79 (1.19) Girls 3.88 (1.31) 5.04 (0.87) Boys 4.34 (1.22) 4.52 (1.18) Girls 4.26 (1.25) 4.87 (0.92) Boys 4.55 (1.34) 4.86 (0.99) Girls 4.00 (1.22) 4.78 (1.18) Boys 4.20 (1.07) 4.70 (1.22) 6 8 10 13 Note. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.