The Standard of Living Debate: A Document Based Essay Activity for

advertisement

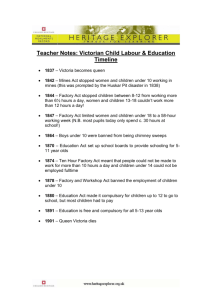

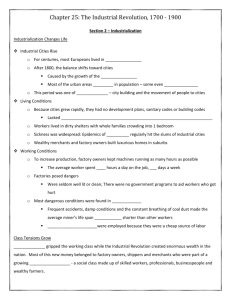

THE STANDARD OF LIVING DEBATE: A DOCUMENT BASED ESSAY ACTIVITY FOR SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS Brenda Santos Bronx Leadership Academy High School Bronx, NY NEH Summer Seminar 2000 Historical Interpretations of the Industrial Revolution in Britain University of Massachusetts Dartmouth at the University of Nottingham Letter to the Teacher This activity applies the philosophy that students learn best through inquiry. The goal is to guide students through a thorough and complex investigation of historical evidence which culminates in the formation of their own conclusions regarding a debated historical issue. The following Document Based Essay Activity poses the question: Was the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the standard of living of the working class positive or negative? Students are provided with a variety of documents; some illustrate an improvement in the standard of living, while others reveal the detrimental effect of industrialization on the living standard of the working classes. The documents vary in difficulty, some requiring very careful analysis to assess the meaning and usefulness of the evidence, and others allowing for differences of interpretation. The goal of the student writing this Document Based Essay is to analyze the evidence, and use it to support his or her thesis, in other words his or her response to the question. A sophisticated essay should not ignore viewpoints which oppose its thesis, but instead point out contradictory evidence and explain why the more convincing evidence leads to the thesis of the essay and not the opposite interpretation. In preparation for this activity, the students should gain familiarity with the topic of industrialization in Britain and the major issues involved with this period of transition. It is 2 suggested that this activity be utilized as a culminating project by the whole class or individual students. Of course, adaptation for the needs of each specific class is best. There are various ways in which this project can be adapted to the needs of different classes. With some students it may be appropriate to select one or a few of the documents for closer analysis. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration provide a useful worksheet for document analysis on line at: http://www.archives.gov/digitaI_classroom/lessons/analysisworksheets/document.html To focus specifically on the paintings featured in the Document Based Activity, project the image in the classroom, and allow students to make observations, first objective statements about what they see and then subjective statements about what the painting might indicate. A teacher may also decide to do a "jigsaw" activity. In order to facilitate this activity, divide the students into groups and direct each group to analyze one of a selection of the documents. Then reconfigure the groups so that each new group contains one member of each of the former groups. Now students may combine their expertise in order to discuss the question of living standard. In some classes, an organized debate might be an appropriate method of approaching this activity. Another effective activity for engaging students with the documents is the "document shuffle," a method developed by Robert DiLorenzo, a master teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School, Bronx, NY. Students, in groups, are provided with a packet of documents, each on a separate sheet of paper, and must determine into what two categories the documents fall. By dividing the documents and naming the categories, students analyze each document and assess the relationship between the different pieces of evidence, gaining an understanding of how the evidence frames a debate between two different points of view. The goal of this activity is to engage students in historical analysis. By participating in the process of historical inquiry and investigation, students will gain a better understanding not merely of the events and issues of history but also of what history as a discipline really is. The 3 documents and their presentation enrich the experience of learning history, a subject many high school students associate with a large, heavy book. Directions: Using the following documents and your knowledge of history, write an essay which addresses the question posed below. Read carefully, and remember to define important terms, brainstorm outside information, and outline your main points before writing. The body of the essay must support your thesis with clear references to the documents. Historical Context Britain is the undisputed birthplace of industrialization. At the turn of the eighteenth century, the country was experiencing gradual but significant and sustained changes in the methods and intensity of production. This was not merely an economic revolution, though. The deeper significance of this revolution was its social consequences, in its own day and into the future. Britain's philosophers and governors have been much consumed by thought and discussion about the implications and repercussions of this fate. At the forefront of this discourse is the standard of living debate. Contemporaries of the industrial period, Robert Southey and Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay were contributors to the competing and ideologically opposed publications, the conservative Quarterly Review and the radical Edinburgh Review, respectively. Although these two never debated directly, their writings reflected the national disagreement over the impact of industrialization on the standard of living of the common Briton. While Macaulay has been called "the first optimist" for his high hopes for industrialized society under laissez faire capitalism, Southey represents a more pessimistic view of uncontrolled capitalism in the industrial world, arguing that government must respond to the social problems caused by industrialism. At the root of this debate is the much disputed question of how industrialization affected the standard of living of the working people. Was the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the standard of living of the working class positive or negative? Support your answer with evidence from the documents and from your own knowledge. Document I 4 Daniel Defoe (1659? 173 1), A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain, 3 vols. 1724 -26, 11, from The Factory System, Vol. 1, Birth and Growth. ...Then it was I began to perceive the reason and nature of the thing, and found that this division of the land into small pieces, and scattering of the dwellings, was occasioned by, and done for the convenience of the business which the people were generally employ'd in, and that, as I said before, though we saw no people stirring without doors, yet they were all full within; for, in short, this whole country, however mountainous, and that no sooner we were down one hill but we mounted another, is yet infinitely full of people; those people all full of business; not a beggar, not an idle person to be seen, except here and there an alms house, where people antient, decrepid, and past labour, might perhaps be found; for it is observable, that the people here, however laborious, generally live to a great age, a certain testimony to the goodness and wholesomness of the country, which is, without doubt, as healthy as any part of England; nor is the health of the people lessen'd, but help'd and establish'd by their being constantly employ'd, and, as we call it, their working hard; so that they find a double advantage by their being always in business... This business is the clothing trade...Document 2 Joseph Wright of Derby (1734 97), The Blacksmith's Shop 1771, 50 1/2 x 41 in. (128.3 x 104.1 cm) Document 3 Letter To the Editors of the Leeds Mercury, by "A Briton," Fixby Hall, near Huddersfield, Sept. 29, 1830. Leeds Mercury, 16 October 1830; from The Factory System, Vol. 11: The Factory System and Society ... Gentlemen, No heart responded with truer accents to the sounds of liberty which were heard in the Leeds Cloth hall Yard, on the 22nd instant, than did mine, and from none could more sincere and earnest prayers arise to the throne of Heaven, that hereafter slavery might only be known to Britain in the Pages of her history. One shade alone obscured my pleasure, arising not from any difference in principle, but from the want of application of the general principle to the whole 5 empire. The pious and able champions of negro liberty and colonial rights should, if I mistake not, have gone farther than they did; or perhaps, to speak more correctly, before they had traveled so far as the West Indies should, at least for a few moments, have sojourned in our own immediate neighbourhood, and have directed the attention of the meeting to scenes of misery, acts of oppression, and victims of slavery, even on the threshold of our homes. Let truth speak out, appalling as the statement may appear. The fact is true. Thousands of our fellow creatures and fellow subjects, both male and female, the miserable inhabitants of a Yorkshire town, (Yorkshire now represented in Parliament by the giant of anti slavery principles) are this very moment existing in a state of slavery, more horrid than are the victims of that hellish system 'colonial slavery'. These innocent creatures drawl out, un pitied, their short but miserable existence, in a place famed for its profession of religious zeal, whose inhabitants are ever foremost in professing 'temperance' and 'reformation', and are striving to outrun their neighbours in missionary exertions, and would fain send the Bible to the farthest comer of the globe aye, in the very place where the anti slavery fever rages most furiously, her apparent charity is not more admired on earth, than her real cruelty is abhorred in Heaven. The very streets which receive the droppings of an 'Anti Slavery Society' are every morning wet by the tears of innocent victims at the accursed shrine of avarice, who are compelled (not by the cart whip of the negro slave driver) but by the dread of the equally appalling thong or strap of the over looker, to hasten, half dressed, but not half fed, to those magazines of British infantile slavery the worsted mills in the town and neighbourhood of Bradford!!! Document 4 Dr. Andrew Ure (1778 1857), The Philosophy of Manufactures, London, 1835. From the pamphlet, "The Gregs and the Factory System at Quarry Bank Mill, Styal." At a distance from the factory stands a handsome house, two storeys high, built for the accommodation of the apprentices. Here are well fed, clothed, educated and lodged under kind superintendence 60 young girls. The female apprentices at Quarry Bank mill come partly from its own parish, partly from Chelsea, but chiefly from the Liverpool workhouse. The proprietors have engaged a man and a 6 woman who take car of them in every way; also a school master and school mistress and a medical practitioner.... Document 5 Dr. Andrew Ure (1778 1857), The Philosophy of Manufactures: or, An Exposition of the Scientific, Moral, and Commerical Economy of the Factory System of Great Britain, 1835, 5 8, 13 14, 17 19, from The Factory System, Vol. 1: Birth and Growth ... The blessings which physico mechanical science has bestowed on society, and the means it has still in store for ameliorating the lot of mankind, has been too little dwelt upon; while, on the other hand, it has been accused of lending itself to the rich capitalists as an instrument for harassing the poor, and of exacting from the operative an accelerated rate of work. It has been said, for example, that the steam engine now drives the power-looms with such velocity as to urge on their attendant weavers at the same rapid pace; but that the hand weaver, not being subjected to this restless agent, can throw his shuttle and move his treddles at his convenience. There is, however, this difference in the two cases, that in the factory, every member of the loom is so adjusted, that the driving force leaves the attendant nearly nothing at all to do, certainly no muscular fatigue to sustain, while it procures for him hood, unfailing wages, besides a healthy workshop gratis: whereas the non factory weaver, having everything to execute by muscular exertion, finds the labour irksome, makes in consequence innumerable short pauses, separately of little account, but great when added together; earns therefore proportionally low wages, while he loses his health by poor diet and the dampness of his hovel. Dr. Carbutt of Manchester says, "With regard to Sir Robert Peel's assertion a few evenings ago, that the hand loom weavers are mostly small farmers, nothing can be a greater mistake; they live, or rather they just keep life together, in the most miserable manner, in the cellars and garrets of the town, working sixteen or eighteen hours for the merest pittance. The constant aim and effect of scientific improvement in manufactures are philanthropic, as to tend to relieve the workmen either from niceties of adjustment which exhaust his mind and fatigue his eyes, or from painful repetition of efforts which distort or wear out his frame.... ... In my recent tour, continued during several months, through the manufacturing districts, I have seen tens of thousands of old, young, and middle aged of both sexes, many of them too 7 feeble to get their daily bread by any of the former modes of industry, earning abundant food, raiment, and domestic accommodation, without perspiring at a single pore, screened meanwhile from the summer's sun and the winter's frost, in apartments more airy and salubrious than those of the metropolis in which our legislative and fashionable aristocracies assemble. In those spacious halls the benignant power of steam summons around him his myriads of willing menials, and assigns to each the regulated task, substituting for painful muscular effort on their part, the energies of his own gigantic arm, and demanding in return only attention and dexterity to correct such little aberrations as casually occur in his workmanship. The gentle docility of this moving force qualifies it for impelling the tiny bobbins of the lace machine with a precision and speed inimitable by the most dexterous hands, directed by the sharpest eyes. Hence, under its auspices, and in obedience to Arkwright's polity, magnificent edifices, surpassing far in number, value, usefulness, and ingenuity of construction, the boasted monuments of Asiatic, Egyptian, and Roman despotism, have, within the short period of fifty years, risen up in this kingdom, to show to what extent capital, industry, and science may augment the resources of a state, while they meliorate the condition of its citizens.... . Document 6 Peter Gaskell (1806 41), Artisans and Machinery: The Moral and Physical Condition of the Manufacturing Population considered with reference to Mechanical Substitutes for Human Labor, ix, 1 2, 61, 66 7, 78, 103, 104, 162, 164 5, 166, 172, 231, 262, 264, 268 9, 276, 277-8. 1836. from The Factory System, Vol. 11: The Factory System and Society ... The employment of children in manufactories ought not to be looked upon as an evil till the present moral and domestic habits of the population are completely reorganized. So long as home education is not found for them, they are to some extent better situated when engaged in light labour, and the labour generally is light which falls to their share. The duration of mill labour, from the natural state of the body during growth, and where there is a previous want of healthy development, is too long. . 8 Document 7 Sir Edwin Chadwick (1800 1890), Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population and on the Means of its Improvement, 1842, 240 4, from The Factory System, Vol. 1: Birth and Growth .....The chief advantages of the improved arrangements of the places of work were, on the side of the workpeople, improved health; security for females and for the young against the dangers of fatal accidents, and less fatigue in the execution of the same amount of work. But beyond these the arrangement of the work in one room had moral advantages of high value. The bad manners and immoralities complained of as attendant on assemblages of workpeople of both sexes in manufactories, generally occur, as may be expected, in small rooms and places where few are employed, and that are secluded from superior inspection and from common observation. But whilst employed in this one large room, the young are under the inspection of the old; the children are in many instances under the inspection of parents, and all under the observation of the whole body of workers, and under the inspection of the employer. It was observed that the moral condition of the females in this room stood comparatively high. It would scarcely be practicable to discriminate the moral effects arising from one cause where several are in operation; but it was stated by ministers that there were fewer cases of illegitimacy and less vice observable among the population engaged in this manufactory than amongst the surrounding population of the labouring class. The comparative circumstances of that population were such as, when examined, would establish the conclusion that it must be so. . Document 8 British Parliamentary Papers: Children's Employment (MINES) 1842 Volumes XV, XVI, and XVII (Reprinted by Irish University Press, Volumes 6, 7, and 8.) Employment of Women and Children in Mines and Collieries, Speech by Lord Ashley in the House of Commons, June 7, 1842. 9 Again, Mr. James Wright says and here I am very anxious for the attention of the House, because I would entreat them to observe how the mischief is first engender, and then perpetuated by the toleration of these practices. Women are allowed to work below [the pits], and because they are so, the evils here stated, continue without abatement: a man would complain and resist, but a woman is submissive"I feel confident (he says) that the exclusion of females will advantage the colliers in a physical point of view, inasmuch as the males will not work on bad roads (females are wrought only where no man can be induced to draw or work; they are mere beasts of burden). This will force the alteration of the economy of the mines." But now mark the effect of the system on women: it causes a total ignorance of all domestic duties; they know nothing that they ought to know; they are rendered unfit for the duties of women by overwork, and become utterly demoralized. In the male the moral effects of the system are very sad, but in the female they are infinitely worse, not alone upon themselves, but upon their families, upon society, and, I may add, upon the country itself It is bad enough if you corrupt the man, but if you corrupt the woman, you poison the waters of life at the very fountain. Sir, it appears that they are wholly disqualified from even learning how to discharge the duties of wife and mother. . Document 9 Report of the Children's Employment Commission, May 1842, Source 19 from Caphouse Colliery Study Pack, National Coal Mining Museum of England. No. 206. Fanny Drake, aged 15. Examined at Overton, near Wakefield, May 9th: - I have been 6 years last September in a pit. I work at Charlesworth's Wood Pit. I hurry by myself , I have hurried to dip side for four or five months. I find it middling hard. It has been a very wet pit before the engine was put up. I have had to hurry up to the calves of my legs in water. It was as bad as this a fortnight at a time; and this was for half a year, last winter; my feet were skinned, and just as if they were scalded, for the water was bad: it had stood some time; and I was off my 10 work owing to it, and had a headache and bleeding at my nose. I go down at 6, and sometimes 7; and I come out at 5, and sometimes 6; at least the banksman has told me it was 6, and after 6, but there's no believing him. We stop at 12; but we have often to go into hole to work at the dinnerhour. We stop to rest half an hour, and odd times longer. I stop to rest at hole with the getter, and there is none else with us. I don't like it so well. Its cold, and there's no pan [fire] in the pit. I'd rather be out of pits altogether. I'd rather wait on my grandmother. I push with my head sometimes, it makes my head sore sometimes, so that I cannot bear it touched: it is soft too. I have often had headaches, and colds, and coughs, and sore throats. I cannot read, I can say my letters. I work for James Greenwood; he is no kin to me. I have a singlet and a shift and petticoat on in the pit. I have had a pair of trousers. The getter I work with wears a flannel waistcoat when he is poorly, but when he is quite well he wears nothing at all. It is about 32 inches high where we hurry, and in some places a yard. [This girl is 4 feet 5 1Ž 2 in. in height, and she looked very healthy. . Document 10 Report on Children's Employment: Mines 1842 Volume 7, p. 218 9. Document 11 Rule, John. The Labouring Classes in Early Industrial England, 1750-1850. Essex: Longman Group UK Limited, 1986, p.89. Document 12 Report on Children's Employment: Mines 1842 Volumes XV, XVI, and XVII (Reprinted by Irish University Press, Volumes 6, 7, and 8). Document 13 E.W. Gray, Notes and Observations written during a Ramble of Seven Weeks, Newbury, 1843. From the pamphlet, "The Gregs and the Factory System at Quarry Bank Mill, Styal." 11 For [the apprentices'] amusement each had a small piece of garden; and in the playground a 'weigh jolt' and a swing are fixed, and the ball and battle dore were lying about. Hours are appointed for school, and the copy books of the eleven Newbury girls were shown to me; and all their performances in this respect were good and creditable to all the parties concerned. . Document 14 Friedrich Engels (1820 1895), The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1844. from the pamphlet, "The Gregs and the Factory System at Quarry Bank Mill, Styal." You come to Manchester; you wish to make yourself acquainted with the state of affairs in England ... you are maid acquainted with a couple of the first Liberal manufacturers, Robert Hyde Greg, perhaps, Edmund Ashworth, Thomas Ashton or others. They are told of your wishes. The manufacturer understands you, knows what he has to do. He accompanies you to his factory in the country; Mr. Greg to Quarry Bank in Cheshire, Mr. Ashworth to Turton near Bolton, Mr. Ashton to Hyde. He leads you through an admirably arranged building, perhaps supplied with ventilators, he calls your attention to the lofty airy rooms, the fine machinery, here and there a healthy looking operative. He gives you an excellent lunch and proposes to you to visit the operatives' homes, he conducts you to the cottages, which look new, clean and neat, and goes with you into this one and that one, naturally only overlookers, mechanics etc., so that you may see families who live wholly from the factory. Among other families you might find that only wife and children work, and the husband dams stockings. The presence of the employer keeps you from asking direct questions; you find everyone well paid, comfortable, comparatively healthy by reason of the country air; you begin to be converted from your exaggerated ideas of misery and starvation. But that the cottage system makes slaves of the operatives, that there may be a truck shop in the neighbourhood, that the people hate the manufacturer, this thy do not pint out to you, because he is present. He has built a school, church, reading room etc. That he uses the school to train children to subordination, that he tolerates in the reading room such prints only as represent the interests of the bourgeoisie, that he dismisses employees if they read Chartist or Socialist papers or books this is all concealed from you ... But woe to the operatives 12 to whom it occurs to think for themselves and become Chartists! For them the paternal affection of the manufacturer comes to a sudden end. . Document 15 Ford Madox Brown (1821 1893), Work 1852 1865, Oil on Canvas, arched top 137 x 197.3 cm. Manchester Art Gallery Document 16 Ernest Jones (1819-1869). 'The Factory Town', in The Battle-Day, and other poem, 82. 1855 "The Factory Town" The night had sunk along the city, It was a bleak and cheerless hour; The wild winds sang their solemn ditty To cold grey wall and blackened tower. The factories gave forth lurid fires From pent up hells within their breast; E'en Etna's burning wrath expires, But man's volcanoes never rest. Women, children, men were toiling, Locked in dungeons close and black, Life's fast failing thread uncoiling Round the wheel, the modern rack! Pen the very stars seemed troubled With the mingled fume and roar; 13 The city like a cauldron bubbled, With its poison boiling o'er. For the reeking walls environ Mingled groups of death and life: Fellow workmen, flesh and iron, Side by side in deadly strife. There, amid the wheels' dull droning And the heavy, choking air, Strength's repining, labour's groaning, And the throttling of depair... Stood half naked infants shivering With heart frost amid the heat; Manhood's shrunken sinews quivering To the engine's horrid beat!... Yet their lord bids proudly wander Stranger eyes thro' factory scenes;' Here are men, and engines yonder'. 'I see nothing but machines... Thinner wanes the rural village, Smokier lies the fallow plain Shrinks the cornfields' pleasant tillage, Fades the orchard's rich domain; And a banished population 14 Festers in the fetid street: Give us, God, to save our nation, Less of cotton, more of wheat. Take us back to lea and wild wood, Back to nature and to Thee! To the child restore his childhood To the man his dignity . Document 17 Grindrod, Ralph Barnes. "The Slaves of the Needle; An Exposure of tile Distressed Condition, Moral and Physical, of Dress Makers, Milliners, Embroiderers, Slop Workers, and c." London: William Brittain, and Charles Gilpin.