Lecture 4: When is a Story More than a Story

advertisement

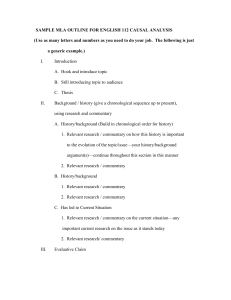

Lecture 4: When is a Story More than a Story? Social Commentary I. Introduction Last time we took a very close look at the American Declaration of Independence. In interpreting the text to locate the argument, we discovered that the DI has an introduction setting up the LOGIC of the argument made. In setting up their beef with King George, the Americans stated that one nation has the right to separate from another when suffering ill treatment is no longer an option. Then the body of the text presents their argument, point by point in logical succession. Each point made is another tally, in American minds, of PROOF of the rightness of American actions. In this section, the writers use appeal both to logic (logos) and to the passion of the reader/listener (pathos) to generate support. Finally, to round out their argument, the framers of the Declaration gave the SO WHAT?, the final result of all the complaints—they formed their own country and called on the support of God. Today, we move away from the type of close reading of texts we've been doing to start looking at how we use critical thinking to judge the past and the world around us. Today we begin to think about the world around us in broader ways than we've been doing. While we'll be talking about the Great Depression through next week, we need to set up the discussion about it, and all the commentary generated during that period by a detailed examination of social commentary. To begin this, we need to backtrack just a little and give us some solid historical grounding. II. The Industrial Age A. Massive Social Upheaval—the period from the late 18th century (1780s), beginning in England, spreading to continental Europe and the US in the 1820s, was one of the greatest technological revolutions in the history of mankind. Some historians argue that not since the 1st agricultural revolution in prehistoric times when people learned to domesticate animals and to harvest crops did a society face so much change. Well, what exactly, was this change? This change is known as the industrial revolution. The Industrial Revolution began slowly, and in fact, did not start with the massive factories at all, but on the family farm. Previous to this, people supplemented their household income (from bad harvests, etc.) with textile work, this was known as the cottage industry. People chose how much they were going to focus on textile manufacture based on the success of their crop for that season. However, as I've said, this system gradually was replaced, and workers were displaced. B. Worker Displacement—the cottage industry, where families had control of when and how much cloth they'd make, was replaced by the "putting-out" system. This system is similar to the cottage industry, but now there were restrictions placed on the worker/laborer. The putting-out system reorganized labor through the introduction of piecework, with capitalists—people who had the moulah—realizing they could make a lot of money if they separated all the pieces/parts that lay in control of workers (let's say textiles, since this was where the transition was made) and separated them into parts, with different families responsible now only for ONE chore (dying, weaving, etc.). This separation was known as piece work. But the problem with piecework was that workers were still locked into pre-industrial work habits. They worked when they wanted to, weren't tied to the clock. The capitalist might come by to pick up his dyed yarn and find that it hadn't been done. Moreover, another problem the capitalist faced in how to get these people to meet their goals was that they could "steal" from him by keeping some yarn for themselves, or weighing inaccurately to get some additional money. And as alluded to, when the demands of the fields called them, the goods of the capitalist would just be sitting there. Thus, something had to be done. Workers had to be moved to a central location where an "eye" could be kept on them. Thus, the early factories were not the big mechanized beasts with assembly lines that we see today. It just put all the work under one roof forcing people to leave home and COME TO WORK. Now they had a time schedule. C. Cities changing—it didn't take long, however, for the cities to change as a consequence of this worker displacement. Factories were not confined to areas near water, so cities built up, people came in to work, and filth increased. Cities became dirtier and the wealthier people moved out to the countryside D. Migration/Immigration—in this pattern of migration out to the country and into the city (for differing reasons), life got worse for the workers. Now they were tied into permanent labor in the factories at low pay, with no kinds of worker benefits. If a hand or finger was severed as they worked, they were dismissed with no pay and no benefits package. They were unfit for work. Additionally, children became employed because of their small, nimble fingers and their ease of being exploited. For example, one of the first factories was a cotton mill for children owned by Richard Arkwright. He literally took orphaned children and housed them to work in his factory. According to Friedrich Engels, mid-19th-century commentator and pal to Karl Marx: "Nobody troubles about the poor as they struggle helplessly in the whirlpool of modern industrial life. The working man may be lucky enough to find employment, if by his labour he can enrich some member of the middle classes. But his wages are so low that they hardly keep body and soul together…The only difference between the old-fashioned slavery and the new is that while the former was openly acknowledged the latter is disguised. The worker appears to be free, because he is not bought and sold outright. He is sold piecemeal by day, the week, or the year…His real masters, the middleclass capitalists, can discard him at any moment and leave him to starve, if they have no further use for his services and no further interest in his survival." III. Social Welfare A. What about the Poor? As we can see by this comment from the mid 19th century (1800s), the poor were essentially tossed aside in this new technological world. People who couldn't pay their bills were often sent to a place called debtors' prison until they could pay their bills (?how can you do that if you're not working?). the poor were the bane of the existence of this new glorious age. They were tossed aside, placed in urban filth and forgotten. B. Changes in Legislating Poor Laws C. Women, Children and Exclusionary Laws—by the mid 19th century in England and the late 19th century in the US, attempts to regulate factory life in the form of state legislation and unionization began. This was a long-fought battle and succeeded, but in many places, the quest for unionization is still being fought. IV. The Modern World and Social Criticism A. World War I—meanwhile, power politics, that is, politics at the level of the nation, still moved on. By 1914, the major European alliances fought could no longer maintain their delicate balance of power. Arguing over land and the distribution of wealth (among other things), the two main European groups, the Triple Alliance (Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary) and the Triple Entente (England, France, Russia) declared war on each other over an assassination and political battle in an area known as Bosnia. WWI lasted until 1918. It introduced high levels of technological warfare (trenches, tanks, mustard gas and machine guns). Most of the war was characterized by stagnation. Not until the US brought fresh troops in 1917 did the stalemate end in Germany's loss. B. Post-War Problems—lots of problems emerged from this. Some of these problems are mentioned in our article on Sacco and Vanzetti. Other problems included: the "lost" generation. Millions of men either killed or maimed—a whole generation of political leaders, etc. gone. Even the men who did survive felt out of touch with society. Economic problems. In Germany high inflation marked the early twenties. As a consequence, not everyone felt so happy about the post-war. There was a definite feeling of doom and gloom. V. How to Deal with this techno-age? A. Writing Fiction—TS Eliot's The WasteLand, the work of Franz Kafka, etc. B. Withdrawing from Society—some people, especially war veterans, never fully fit back into society. Thus they either withdrew completely or formed their own societies in the forms of paramilitary groups. These would set the stage for the darker thirties C. Social Commentary—another way people dealt with this time was to fall back on the age old tradition of social commentary. It was nothing new in the 1920s and 1930s, but it did become more accessible as literacy rates in the 20th century exceeded previous eras. People invoke social commentary for a few reasons: 1. to caricature political and social traditions 2. to make people aware of the world 3. to push for change 4. types—music, photographs, posters, writings VI. Conclusion—the music you heard at the beginning of class, and the readings you had for today and over the next week are forms of social commentary. They try to make people aware of certain circumstances and in their enunciation they hope to make change. VII. Setting up for George Orwell