1 Introduction to bioinformatics

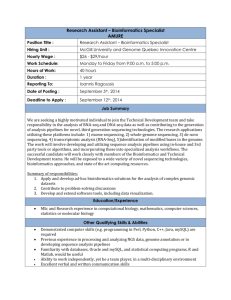

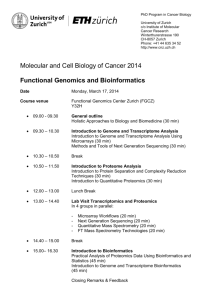

advertisement

Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) 1 INTRODUCTION TO BIOINFORMATICS Table of contents: Introduction to bioinformatics 1 Introduction to bioinformatics ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Voorwoord Bio-informatica ................................................................................................. 2 1.2. Bioinformatics formal definition ......................................................................................... 5 1.3. Driving force for bioinformatics: ......................................................................................... 5 1.3.1 Advance in molecular biology ......................................................................................... 5 1.4. Different subfields in bioinformatics research ..................................................................... 6 1.5. Structural genomics.............................................................................................................. 8 1.5.1 Overview .......................................................................................................................... 8 1.5.2 Biological application: genome sequencing .................................................................. 12 1.6. Comparative genomics ....................................................................................................... 18 1.6.1 Overview ........................................................................................................................ 18 1.6.2 Biological application 1: comparative genomics, genome evolution (Y. Van de Peer) 19 1.6.3 Biological application 2: metagenomics (G. Venter)..................................................... 22 1.7. Functional genomics & Systems Biology .......................................................................... 24 1.7.1 Systems biology ............................................................................................................. 24 1.7.2 Synthetic biology from an engineering point of view: rational design .......................... 25 Updated 20/09/2013 Master file introduction Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 1 Introduction 1.1. Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Voorwoord Bio-informatica Bio-informatica, hoewel een relatief recente term, bestaat reeds meer dan 400 jaar. Galileo schreef immers “the book of nature is written in the language of mathematics!”. Het gebruik van wiskundige modellen om biologische fenomenen te verklaren en gegevens te analyseren is zeker niet nieuw. Tot nog toe was het enkel gemeengoed in bepaalde deeldomeinen van de biologie (e.g. populatiegenetica, fylogenie, “molecular modeling” etc.). Belangrijke technologische vernieuwingen in de moleculaire biologie in het begin van de jaren ‘90 brachten hierin grondige verandering. De toepassing van de hoge-doorvoer technologieën (genomica, transcriptomica, proteomica, metabolomica) laat immers toe om in zeer korte tijd de DNA-sequentie van hele genomen in kaart te brengen, de expressie van duizenden genen of proteïnen in een organisme te analyseren, de aard en concentratie van alle metabolieten te evalueren en de interacties tussen deze verschillende genetische entiteiten te identificeren. Dit heeft geleid tot een onevenaarbare data-explosie. Voor het analyseren van deze data volstaat een excel spread sheet niet langer, maar is een interdisciplinaire aanpak noodzakelijk Deze dataexplosie heeft ook geleid tot een drastische verruiming in het “biologisch” denken (ook wel de nieuwe biologie geheten). De finale doelstelling van de moleculaire biologie “het verwerven van inzicht in de werking en evolutie van organismen” bleef dezelfde. De manier om dit doel te bereiken is gewijzigd. Tot voor enkele jaren werden in het functioneel moleculair biologisch onderzoek, genen, proteïnen en andere moleculen één voor één als geïsoleerde entiteiten bestudeerd. Het gebruik van de nieuwe technologieën situeert de functie van een gen nu in een globale context, namelijk als deel van een complex regulatorisch netwerk. Vanuit dit nieuw perspectief wordt het organisme beschouwd als een systeem dat interageert met zijn omgeving. Het gedrag ervan wordt bepaald door de complexe dynamische interacties tussen genen/proteïnen/metabolieten op het niveau van het regulatorische netwerk. Door de beschikbaarheid van data van verschillende modelorganismen kunnen bovendien de cellulaire mechanismen tussen de organismen vergeleken worden. Organisme voorgesteld als een systeem dat interageert met zijn omgeving. Via de werking van regulatorische netwerken past een organisme zich voortdurend aan aan wisselende omgevingssignalen. Deze aanpassingen resulteren in een gewijzigd gedrag of fenotype. De regulatorische netwerken kunnen beschouwd worden als de biologische signaalverwerkingssystemen. Traditionele studies van biologische systemen waren veeleer beschrijvend. De systeembenadering van de biologie impliceert echter een doorgedreven kwantitatieve en geïntegreerde analyse van complexe gegevens. Onder invloed van deze nieuwe tendens ontstond de term "bio-informatica" (voor het eerst gebruikt in de rond 1993) en werd de hoge-doorvoer functionele moleculaire biologie een deel van de “systeembiologie”. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 2 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Zoals de moleculaire biologie zijn systeembiologie en bio-informatica onderzoeksdomeinen met vele deeldisciplines (structurele, functionele, comparatieve bio-informatica). De bio-informatica vraagstelling ontstaat vanuit de biologie. De computationele wetenschappen stellen een arsenaal standaardalgoritmes en principes ter beschikking. Beide moeten op een zinvolle manier verenigd worden, rekening houdend zowel met de specifieke eigenschappen van het gebruikte algoritme als met deze van het biologisch probleem. Het verzoenen van algoritmen uit exacte wetenschappen met experimentele data afkomstig van stochastische biologische systemen vormt hierbij de belangrijkste uitdaging. Om die reden kan het oplossen van een biologisch probleem via computationele weg al snel een paar jaar onderzoek in beslag nemen maar leidt het tot waardevolle resultaten die in sommige gevallen het traditioneel biologisch onderzoek overstijgen. Toekomst van bio-informatica Bio-informatica is dus geen “hype”. Naarmate de moleculair biologische technologie evolueert zal ze verder aan belang toenemen. De meest succesvolle moleculair biologische laboratoria zullen daarbij ongetwijfeld deze zijn, die het “wet lab” onderzoek sturen a.h.v. de predicties van geavanceerd computioneel onderzoek. De toekomst van zowel de moleculaire biologie als de bioinformatica ligt in de uitbouw van het onderzoek waarbij de grens tussen het “wet lab” en het computationeel aspect vervaagt. Doel van de cursus bio-informatica Het doel van de cursus is tweeledig: De eerste en waarschijnlijk meest belangrijke doelstelling is om jullie ervan te overtuigen dat bioinformatica een essentieel onderdeel is van jullie curriculum. Met een aantal voorbeelden en verwezenlijkingen uit het domein hoop ik jullie van te kunnen overtuigen dat ‘bioinformatica’ en ‘systeem biologie’ ons leven en denken zullen veranderen.De moleculaire bioloog van de 21e eeuw zal niet enkel beschikken over een goed uitgebouwde biologische kennis, maar hij dient ook vertrouwd te zijn met belangrijke principes uit de wiskunde, de statistiek en de informatietechnologie. Dergelijke integratie van biologisch inzicht, analytisch en probleemoplossend denken is eigen aan de bioinformatica. Een tweede aspect van de cursus is om jullie vertrouwd te maken met het gebruik van bioinformatica tools. Het bio-informatica domein is echter zeer ruim en in volle expansie. Het is dan ook onmogelijk om alle tools en onderdelen te belichten. We zullen een aantal belangrijke en veel gebruikte voorbeelden bespreken. Het is hierbij van belang dat jullie realisereb dat zinvolle bio-informatica meer is dan enkel het toepassen van tools maar dat het essentieel is om ook de onderliggende mathematische principes van deze tools te begrijpen en tegelijk inzicht te verwerven in de datageneratieprotocols en de biologische complexiteit. Dit impliceert dat bio-informatica meer is dan een hulpmiddel bij het moleculair biologisch onderzoek maar dat het een volwaardig onderzoeksdomein op zichtzelf vormt. K. Marchal Important messages you should realize after having followed the course: How can bioinformatics change the world? Answer: Bioinformatics has numerous application domains, and will for instance revolutionize the medical field, because it for example will make personalized medicine possible. Now that the genome (the blueprints of life) of everyone can (and will) get sequenced, we can start investigating why some persons are susceptible to certain diseases while others are not, and why a certain treatment works for some and not for others. In agriculture, we can for instance study why certain Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 3 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) plants are more resistant to drought than others, which is important in these days of global warming and climate change. Bioinformatics can also address more fundamental questions in evolutionary biology, such as whether Neanderthals and the ancestor of modern humans ever had sex (the answer is yes), questions that can only be addressed with bioinformatics or computational biology. What is the most important skill of being a bioinformatician Well, I think first of all you need to be a generalist rather than a specialist. You need to know a bit of everything but nothing too much in detail (that can even be disadvantageous I think). To give an example: wet lab scientists typically have a very detailed view on biology: biological systems have randomly evolved into emerging complex systems that can not be captured in a few rules. There are more exceptions than fixed rules in biology. Engineers on the other hand model systems and these models depend on predefined rules. As a bioinformatician you need to keep both parties happy: a good formalization of a biological question should reduce the problem to a model that is mathematically tractable but that still captures the intricacies the biologist is interested in. Finding the right assumptions and simplifications builds on this generic knowledge. This generic knowledge is also key to the scientific Intuition you need to have as a bioinformatician. As was already mentioned: with bioinformatics we can solve research questions that could not be addressed before. There is so much data out there that when you integrate it all you can tackle research questions that go far beyond what was accessible or could be dreamt of by a single person or even a single lab. The difficulty often is defining these novel research questions or hypothesis no one has ever thought of before. This again requires very good interdisciplinary knowledge on how the data was generated, what type of information does it contain, how can it be integrated etc. If Bioinformatics will become so prominent and is referred to as ‘the new biology’, how will this effect the more classical wet lab science? Answer: Of course without data there is no bioinformatics. But there is indeed a tendency that increasingly, data generation becomes robotized or outsourced. This has a consequence that wet lab scientists have more time left to spend on the design of their experiment and will be confronted at a much earlier stage with the analysis of their data, and the problems related to this. What do you hope to to get out of your data, how will you synthesize all these data, what is the hypothesis you want to formulate, and so on? So rather than focusing on a single gene, they will need to start thinking more globally, solving the bigger picture and that is what the term ‘new biology’ is referring to. This is now often considered the problem of the bioinformatician but obviously, the wet lab scientist of the future will have to adopt at least some of those skills. So the distinction between a bioinformatician and a wet lab scientist (systems biologist) will become fuzzier and In the coming decades, we expect that about one third of the people in the life sciences will be bioinformaticians or at least use some sort of bioinformatics in their research. However, although genome hackers and number crunchers can learn a lot from the loads of data generated, wet lab work will always be necessary. Bioinformatics is also often about making predictions, but of course these still will need to be validated in the lab. On the other hand, for some specific fields such as evolutionary research, bioinformatics is often sufficient or even the only way to obtain results. Taken from an interview in the framework of N2N (bioinformatics speerpunt at the UGhent) Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 4 Introduction 1.2. Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Bioinformatics formal definition Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary research area at the interface between biological and computational sciences. Although the term 'Bioinformatics' is not really well-defined, you could say that this scientific field deals with the computational management of all kinds of molecular biological information. Most of the bioinformatics work that is being done deals with either analyzing biological data, or with the organization of biological information. As a consequence of the large amount of data produced in the field of molecular biology, most of the current bioinformatics projects deal with structural and functional aspects of genes and proteins. 1.3. Driving force for bioinformatics: 1.3.1 Advance in molecular biology Traditional genetics and molecular biology have been directed toward understanding the role of a particular gene or protein in a molecular biological process. A gene is sequenced to predict its function or to manipulate its activity or expression. Traditional molecular biology was focusing on single genes. With the advent of novel molecular biological techniques such as genome scale sequencing, large scale expression analysis (gene, protein expression, microarrays, 2Delectrophoresis, mass spectroscopy), large scale identification of protein-protein interactions (yeast 2 hybrid; protein chips) or protein-DNA interactions (immunochromatine precipitation), the scale of molecular biology has changed. One is no longer focusing on a single gene but many genes or proteins are analyzed simultaneously (i.e. at high throughput level transcriptomics, translatomics interactomics, metabolomics). This novel approach offers advantages: one can study the function or the expression of a gene in a global context of the cell. Because a gene does not act on its own, it is always embedded in a larger network (systems biology). These holistic approaches allow better understanding of fundamental molecular biological processes. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 5 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) On the other hand, high throughput approaches pose several novel challenges to molecular biology: the analysis of such large scale data is no longer trivial. Simple spreadsheet analysis such as excel are no longer sufficient. More advanced datamining procedures become necessary. Another urgent problem is also how to store and organize all the information. There is, in fact, an inseparable relationship between the experimental and the computational aspects. On the one hand, data resulting from high-throughput experimentation require intensive computational interpretation and evaluation. On the other hand, computational methods produce questionable predictions that should be reviewed and confirmed through experiments. 1.4. Different subfields in bioinformatics research This intricate merge between molecular biology and computational biology has given rise to new research fields and application. In each of these research fields, a specific field of bioinformatics expertise is required. Three main fields can be distinguished: Structural genomics, o Input: raw sequence data o Goal: annotation o Bioinformatics Tools: genome assembly, gene/promoter/intron prediction Comparative genomics o Input: annotated genomes o Goal: annotation, evolutionary genomics o Bioinformatics Tools: sequence alignment, tree construction Functional genomics. o Input: experimental information o Goal: function assignment, systems biology o Bioinformatics Tools: microarray analysis, network reconstruction, dataintegration Note that the field of molecular dynamics and protein modeling is not covered in this course. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 6 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Structural Genomics/Annotation Comparative Genomics/ evolutionary biology Functional genomics/ Systems Biology For some purposes, different subfield have to be combined i.e., the distinction is not always a s clear cut as it seems. For instance, for genome annotation: As these genomes are collected they need to be annotated. This means that we will have To identify the location of the genes on the genome (structural annotation) To assign a function to each of the potential genes (functional annotation). In structural annotation, the question to be answered is 'where are the genes'? One needs to localize the gene elements on the sequence (chromosome) and find the coding sequences, intergenic sequences, exons/intro boundaries, promoters, 5'UTR, 3'UTR regions, and so on. In functional annotation, one tries to get information on the function of genes. Often, it is possible to get hints on the biochemical function of the gene products by finding homologs in protein databases or by studying the biochemical characteristics of the gene (proteome, transcriptome analysis). In the following, each of the bioinformatics subfields will be briefly described and illustrated with a biological case study. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 7 Introduction 1.5. 1.5.1 Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Structural genomics Overview Structural genomics is based on raw sequence data. The first step in structural genomics consists of assembling raw sequence fragments into contigs or whole genomes. The complexity of the assembly process depends on the used sequence technique. Two major sequencing approaches will be described below: For more information see also http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/articles/06_00/sequence_primer.shtml http://www.bio.davidson.edu/courses/genomics/method/shotgun.html In a second step the genetic entities need to be located on the genome (structural annotation). SEQUENCING AND GENOME ASSEMBLY 1.1.5.1.1 Top down sequencing The first genome sequencing approach “top down” is based on the known order of DNA fragments. To sequence larger molecules such as human chromosomes, 1) individual chromosomes are broken into random fragments of approximately 150 kb. 2) These fragments are then cloned into BACs (vectors). 3) In an intensive but largely automated laboratory procedure, the resulting library is screened for clusters of fragments called contigs which have overlapping or common sequences. These contigs are then joined to produce an integrated physical map of the genome based on the order of the BACS. Once the correct map has been identified unique overlapping clones are chosen for sequencing. 4) However, these clones are too large for direct sequencing. One procedure for sequencing these subclones is to subclone them further into smaller fragments that are of sizes suitable for sequencing (500 bp). 5) From the DNA sequences of approximate length of 500 bp, genome sequences are assembled using the fragment order on the physical map as a guide. Top down sequencing 2. 1. Genome fragmentation 3. BAC library 4. Physical map Subclone library Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 8 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) 5. Genome assembly This method of creating physical maps of genomes and then using this map to guide the sequencing was used by the Public Human genome Consortium to create a draft of the human genome. This carefully crafted, but laborious procedure was designed to produce a sequence of the human genome that was based on a top down approach, at each stage using the physical map to guide the placement of sequences (Lander, Nature 2001). The reasoning behind this strategy was the avoidance of sequence repeats that might otherwise confound obtaining the correct genome sequence. 1.1.5.1.2 Shot gun sequencing A contrasting “bottom-up” method in which the genome sequence is derived from solely overlaps in large numbers of random sequence without using the physical map as a guide, has been devised. This alternative method, called shotgun sequencing attempts to assemble a linear map from subclone sequences without knowing their order on the chromosome. Contigs are assembled based on alignment of all possible sequence pairs in the computer. This method is now routinely used to sequence microbial genomes and the cloned fragments of larger clones (see also metagenomics). Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 9 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Shot Gun Sequencing 1. Genome fragmentation 2. Library 3. Sequences 4. Genome assembly The shotgun method was used by Celera Genomics to sequence the human genomes (Venter, Science 2001; http://www.jcvi.org/). There has since been controversy as to whether or not use of the public data by the Venter group contributed significantly to their draft of the human genome or from the overlaps in a highly redundant set of fragments by automatic computational methods (shotgun method). Fuzz about the public versus the commercial effort (lander versus venter) http://www.dnalc.org/view/15326-Analysis-in-public-and-private-Human-Genome-Projects-EricLander-.html Nowadays for large genomes a combination between top down and bottom up sequencing is used as illustrated below. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 10 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) STRUCTURAL ANNOTATION Once assembled, structural elements such as the location of genes, introns, exons, splice sites, promoters, repeated elements etc.need to be predicted in the genome (the structural analysis). Distinct gene predictions algorithms have been developed. Methods for ab initio gene predictions are based on supervised machine learning techniques(1). The model (e.g. a hidden markov model or a neural network) is trained on a set of known genes (or promoters or introns) and subsequently used to predict the location of unknown genes (or promoters or introns) in an organism. Features (properties in the genome) that are extracted from the trainingsset and that thus help recognizing genes are for instance specific codon usage (which differs between coding and non coding regions), spice site recognition sites (when predicting splice sites) etc. Because of differences in codon usage and splice junctions between organisms, a model must be trained for each novel genome (see chapter “gene prediction”). Once the complete genome is known genome maps can be constructed that indicate the position of each gene on the genome. Comparing gene maps of different organisms allows identification of translocation or other chromosome arrangements (important in cancer research). Fig. genome map of the bacterium A. tumefaciens Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 11 Introduction 1.5.2 Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Biological application: genome sequencing THE NUMBER OF FULLY SEQUENCED GENOMES INCREASES WITH AN UNPRECEDENTED PACE The first bacterial genome to be sequenced was that of Haemophilus influenzae (sequenced by the TIGR institute (http://www.tigr.org) in 1995). The success of sequencing this genome in relatively short time heralded the sequencing of a large number of additional prokaryotic organisms. To data the genomes 96 of these species have been sequenced among which the model organisms E. coli and B. subtilis. Later on eukarotic genomes were sequenced. In 2002 the human genome sequence was completed by two distinct research groups in parallel: a commercial group Celera and an academic sequence consortium (Sanger Center). Nowadays the sequences of several eukaryotic model organisms have been determined and the number of sequences is steadily increasing. Microbial genomes http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/static/micr.html Genome resources at ncbi: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Genome Vertebrate genomes: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/map_search.cgi?taxid=7227 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/human/ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/mouse/index.html http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/rat/index.html http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/zebrafish/index.html http://www.ensembl.org/ yeast genomes http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/map_search.cgi?chr=scerevisiae.inf Plant genomes: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMGifs/Genomes/Resources_1.html#arab Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 12 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) From Nature Reviews Genetics 4, 251-262 (2003); GENOME SEQUENCES AT INTERSPECIES LEVEL Why are these genomes useful. Below 2 examples of using genome sequences are described. With all these genome sequences at hand, it becomes even possible to study our own evolution. In September 2006, an international team published the genome of our closest relative, the chimpanzee. With the human genome already in hand, researchers could begin to line up chimp and human DNA and examine, one by one, the 40 million evolutionary events that separate them from us. The genome data confirm our close kinship with chimps: We differ by only about 1% in the nucleotide bases that can be aligned between our two species, and the average protein differs by less than two amino acids. Given the dramatic behavioral and developmental differences that have arisen since their divergence from a common ancestor 6-7 million years ago, the question therefore arises of how these phenotypic differences are reflected at the genome sequence level. Recent studies have shown that mainly genes involved in smell and hearing are significantly different between humans and chimpanzees. Also changes in gene regulatory binding sequences (promoters, enhancers, and silencers) are likely to have contributed to divergence between humans and chimps. Using a comparative approach, it has been shown that regulatory binding sites lost in human but still present in chimp are located in specific genomic regions and are associated with genes involved in sensory perception. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 13 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) In this figure, two examples are given of regulatory binding sites that changed between human and chimp. Note how small differences in sequences can have such large phenotypic influences. GENOME SEQUENCES AT THE LEVEL OF THE INDIVIDUAL In the early days most genomes were sequenced by the classical Sanger sequencing approach (see figure below), but nowadays the next-generation sequencing (NGS) methodology is taken over. Mainly the developments in nanotechnology have resulted in the origin of novel technologies for sequencing and synthesizing DNA sequences. Next-generation sequencing has the ability to process millions of sequence reads in parallel rather than 96 at a time. All NGS platforms share a common technological feature, reactions. massively parallel sequencing of clonally amplified or single DNA molecules that are spatially separated in a flow cell (for a recent review see Metzker, M.L. (2010) Nature Reviews Genetics 11:31-46) (see figure below). This design is a paradigm shift from that of Sanger sequencing, which is based on the electrophoretic separation of chain-termination products produced in individual sequencing reactions. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 14 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Fig. Sanger sequencing methodology: The dideoxynucleotide termination DNA sequencing technology invented by Fred Sanger and colleagues in 1977, formed the basis for DNA sequencing from its inception through 2004. Originally based on radioactive labeling, the method was automated by the use of fluorescent labeling coupled with excitation and detection on dedicated instruments, with fragment separation by slab gel and ultimately by capillary gel electrophoresis. Overview of next generation sequencing technologies. The breakthroughs in these technologies are unpreceded and follow the law of Moore. Related to the sequencing technology, it is to be expected that within a few years we will have the 100 dollar genome, which allows the genome of a human to be sequenced within a few hours for 1000 dollar. (comparison the human genome is 3.4 Gb=3.4 miljard baseparen en heeft 20000-25000 genen). As a result recent sequencing projects start focusing on sequencing different individuals of the same species (1000 genomes project e.g. http://www.1000genomes.org/). This has been made possible thanks to the lower sequencing cost of the next generation sequencing approaches. This opens novel perspectives for amongst others, personalized medicine, sequence-based trait selection, evolution experiments. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 15 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) The ‘1000 genomes project’ Recent improvements in sequencing technology ("next-gen" sequencing platforms) have sharply reduced the cost of sequencing. The 1000 Genomes Project is the first project to sequence the genomes of a large number of people, to provide a comprehensive resource on human genetic variation. As with other major human genome reference projects, data from the 1000 Genomes Project will be made available quickly to the worldwide scientific community through freely accessible public databases. (See Data use statement.) The goal of the 1000 Genomes Project is to find the genetic variants that have frequencies of at least 1% in the populations studied. This goal can be attained by sequencing many individuals lightly. To sequence a person's genome, many copies of the DNA are broken into short pieces and each piece is sequenced. The many copies of DNA mean that the DNA pieces are more-or-less randomly distributed across the genome. The pieces are then aligned to the reference sequence and joined together. To find the complete genomic sequence of one person with current sequencing platforms requires sequencing that person's DNA the equivalent of about 28 times (called 28X). If the amount of sequence done is only an average of once across the genome (1X), then much of the sequence will be missed, because some genomic locations will be covered by several pieces while others will have none. The deeper the sequencing coverage, the more of the genome will be covered at least once. Also, people are diploid; the deeper the sequencing coverage, the more likely that both chromosomes at a location will be included. In addition, deeper coverage is particularly useful for detecting structural variants, and allows sequencing errors to be corrected. Sequencing is still too expensive to deeply sequence the many samples being studied for this project. However, any particular region of the genome generally contains a limited number of haplotypes. Data can be combined across many samples to allow efficient detection of most of the variants in a region. The Project currently plans to sequence each sample to about 4X coverage; at this depth sequencing cannot provide the complete genotype of each sample, but should allow the detection of most variants with frequencies as low as 1%. Combining the data from 2500 samples should allow highly accurate estimation (imputation) of the variants and genotypes for each sample that were not seen directly by the light sequencing. [definition haplotype A haplotype in genetics is a combination of alleles (DNA sequences) at adjacent locations (loci) on the chromosome that are transmitted together. A haplotype may be one locus, several loci, or an entire chromosome depending on the number of recombination events that have occurred between a given set of loci. The data now available to scientists contains 99% of all genetic variants that occur in the populations studied, down to the level of rare variations that only occur in 1 out of every 100 Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 16 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) people. "The whole point of this resource is that we're moving to a point where individuals are being sequenced in clinical settings and what you want to do there is sift through the variants you find in an individual and interpret them," said Professor Gil McVean of Oxford University, a lead author for the study. The information will be pored over by thousands of researchers, who will analyse and interpret the DNA variations between people in a bid to work out which ones are implicated in disease. In addition to the DNA sequences, the 1,000 Genomes Project has stored cell samples from all the people it has sequenced, to allow future scientific projects to look at the biological effect of the DNA variations they might want to study. How is this done e.g. through a GWAS. Genome wide association studies (GWAS): Any two human genomes differ in millions of different ways. There are small variations in the individual nucleotides of the genomes (SNPs) as well as many larger variations, such as deletions, insertions and copy number variations. Any of these may cause alterations in an individual's traits, or phenotype, which can be anything from disease risk to physical properties such as height. In a genetic association study one asks if the allele of a genetic variant is found more often than expected in individuals with the phenotype of interest (e.g. with the disease being studied). Overview of a genomewide association study, from W. Gregory Feero et al 2010Th e new england journal of medicine. The most common approach of GWA studies is the case-control setup which compares two large groups of individuals, one healthy control group and one case group affected by a disease. All individuals in each group are genotyped for the majority of common known SNPs. The exact number of SNPs depends on the genotyping technology, but are typically one million or more. For each of these SNPs it is then investigated if the allele frequency is significantly altered between the case and the control group. In such setups, the fundamental unit for reporting effect sizes is the odds ratio. The odds ratio reports the ratio between two proportions, which in the context of GWA studies are the proportion of individuals in the case group having a specific allele, and the Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 17 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) proportions of individuals in the control group having the same allele. When the allele frequency in the case group is much higher than in the control group, the odds ratio will be higher than 1, and vice versa for lower allele frequency. Additionally, a P-value for the significance of the odds ratio is typically calculated. Finding odds ratios that are significantly different from 1 is the objective of the GWA study because this shows that a SNP is associated with disease. There are several variations to this case-control approach. A common alternative to case-control GWA studies is the analysis of quantitative phenotypic data, e.g. height or biomarker concentrations or even gene expression. In addition to the calculation of association, it is common to take several variables into account that could potentially confound the results. Sex and age are common examples of this. Moreover, it is also known that many genetic variations are associated with the geographical and historical populations in which the mutations first arose. Because of this association, studies must take account of the geographical and ethnical background of participants by controlling for what is called population stratification. Key to the application of GWA studies was the International HapMap Project and the 1000 genomes project which allowed to identify a majority of the common SNPs which are customarily interrogated in a GWA study. 1.6. 1.6.1 Comparative genomics Overview The basic idea of comparative genomics is the comparison of sequences between genomes. Sequence alignment methodologies form the basis tools for comparative genomics (Blast, clustalW, Needleman Wunsh, Markov models…) (see chapter sequence alignment). 1) Comparative genomics can be used to aid or validate gene predictions: Since gene prediction methods based on sequence features only (ab initio gene prediction) are only partially accurate, gene identification is facilitated by high-throughput sequencing of partial cDNA copies of expressed genes (called expressed sequence tags or ESTs). Presence of ESTs confirms that the predicted gene is transcribed. A more through sequencing of full length cDNA clone may be necessary to confirm the structure of genes. Gene prediction methods that not only take into account sequence features (codon usage, intron exon recognition sites), but also sequence homology (with ESTs, cDNAs, proteins) are called extrinsic gene finding methods (and are in fact a combination of structural and comparative genomics). An example is the genewise method discussed in chapter gene prediction. 2) Homology based annotation: The amino acid sequence of proteins encoded by the predicted genes can be used as a query sequence in a database similarity search. A match of a predicted protein sequence to one or more database sequences not only serves to validate the gene prediction, but also can give indications on the function of the gene. Not all genes will give hits in database searches. Some proteins might be unique for a certain organism or might not have been characterized before. In such cases it might also be important to search for characteristic domains (conserved amino acid patterns that can be aligned) that represent a structural fold or a biochemical feature (see chapter pattern searches). 3) Another important goal of comparative genomics is the study of protein families i.e., all proteins are compared in two or more proteomes. Orthologs are genes that are so highly conserved by Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 18 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) sequence in different genomes that the proteins they encode are strongly predicted to have the same structure and function and to have arisen from a common ancestor through speciation. Paralogs have arisen by duplication events and might have a distinct function (see chapter comparative genomics). Highly similar proteins (both orthologs and paralogs) form protein families. They can be identified by reciprocal blast searches or by cluster analysis (see COGs). In related organisms both gene content of the genome and gene order on the chromosome are likely to be conserved. As the relationship between organisms decreases local groups of genes remain clustered but chromosomal rearrangements move the clusters to other locations (see chapter comparative genomics). Evolutionary modeling at genome level can therefore include the following analyses: 1) the prediction of chromosomal rearrangements, analysis of duplications at the level of protein domain gene chromosome or full genome level search for horizontal transfer between separate organisms. 4) Phylogenetic footprinting is still another application of comparative genomics. Currently we have very limited information about regulatory elements especially in complex eukaryotes. Comparison of orthologous chromosomal regions in reasonably distantly related species should lead to identification of common regulatory elements (see chapter motif detection). 1.6.2 Biological application 1: comparative genomics, genome evolution (Y. Van de Peer) STUDYING GENOME EVOLUTION Fossil records of plant evolution The extant (or modern) angiosperms did not appear until the Early Cretaceous (145–125 Mya), when the final combination of these three angiosperm features occurred, as supported by evidence from micro- and macrofossils and clear documentation of all of the major lines of flowering plants. This diversification of angiosperms occurred during a period (the Aptian, 125–112Mya; Figure 1) when their pollen and megafossils were rare components of terrestrial floras and species diversity was low. Angiosperm fossils show a dramatic increase in diversity between the Albian (112–99.6 Mya) and the Cenomanian (99.6–93.5 Mya) at a global scale (Figure 1). The angiosperm radiation yielded species with new growth architectures and new ecological roles. Early angiosperms had small flowers with a limited number of parts that were probably pollinated by a variety of insect taxa but specialized for none. Accordingly, Cenomanian flowers do not yet provide strong evidence for specialization of pollination syndromes. However, by the Turonian (93.5–89.3 Mya), flowering plants had a wide variety of features that are, in extant species, closely associated with several types of specialized insect pollination and with high species diversity within angiosperm subclades. The evolution of larger seed size in many angiosperm lineages during the early Cenozoic (from 65 Mya) indicates that animal-mediated dispersal and shade-tolerant lifehistory strategies. In summary, fossils with affinities to diverse angiosperm lineages, including monocots, are all found in Early Cretaceous floras. However, the question remains why this was such a decisive time in the evolution of plants. Can whole-genome duplication events have had a key role in the origin of angiosperms and their morphological and ecological diversification. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 19 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Evolution of angiosperms based on fossil records Specialised flowering plants Unspecialised flowering plants Dramatic increase in diversity (aptian) extant (or modern) angiosperms 130 Mya Why was this such a decisive time in plant evolution ? Evidences: Many angiosperms have experienced one or more episodes of polyploidy in their ancestry. o Duplicated genes and genomes can provide the raw material for evolutionary diversification and the functional divergence of duplicated genes o The dates of the duplication events correspond to time periods of large expansion in angiosperms as recorded based on fossils. Corresponds with age older Genes involved in transcriptional regulation and signal transduction have been preferentially retained following genome duplications. Similarly, developmental genes have been observed to be retained following genome duplications, particularly following the two oldest events (1R and 2R). Few regulatory and developmental gene duplicates appear to have survived small-scale duplication events. Their rapid loss can be explained by the fact that transcription factors and genes involved in signal transduction tend to show a high dosage effect in multicellular eukaryotes. The expression of a wide range of genes regulated by these proteins show major perturbations when only one regulatory component is duplicated, Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 20 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) rather than all components that govern a certain pathway. Furthermore, that transcription factors and kinases are often active as protein complexes and must be present in stoichiometric quantities for their correct functioning is congruent with their high retention rate following whole-genome instead of small-scale duplication events. Regulatory and developmental genes are thought to have been of primordial importance for the evolution of morphological complexity in plants and animals. Genes involved in secondary metabolism or responses to biotic stimuli, such as pathogen attack, tend to be preserved regardless of the mode of duplication. Because plants are sessile organisms, secondary metabolite pathways, as well as genes governing responses to biotic stimuli, are crucial to the development of survival strategies against herbivores, insects, snails and plant pathogens. Additionally, in angiosperms, anthocyanins and other secondary metabolites give rise to colourful and scented flowers that attract pollen- and nectarcollecting animals. Thus, secondary metabolite diversification might have led to more efficient seed dispersal (compared with wind pollination, which is widespread in most seed plants) and might have provided new possibilities for reproductive isolation and the elevation of speciation rates. The finding that genes involved in secondary metabolism and responses to biotic stimuli are also strongly retained following (continuously occurring) small-scale gene duplications might reflect the continuous interaction between plants and animals, fungi or plant pathogens imposing a constant need for adaptation. By contrast, genes involved in responses to abiotic stress, such as drought, cold and salinity, appear to have been only moderately retained after small-scale gene duplication events [17], indicating that they might have been required at more specific times in evolution, such as during major environmental changes or adaptation to new niches. Interestingly, 1R and 2R might have occurred during a period of increased tectonic activity linked to highly elevated atmospheric CO2 levels Bioinformatics methods used Field of comparative genomics and phylogeny. Methodologies mainly based on sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 21 Introduction 1.6.3 Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Biological application 2: metagenomics (G. Venter) METAGENOMICS: DNA SEQUENCING OF ENVIRONMENTAL SAMPLES Nature Reviews Genetics 6, 805-814 (2005); doi:10.1038/nrg1709 Although genomics has classically focused on pure, easy-to-obtain samples, such as microbes that grow readily in culture or large animals and plants, these organisms represent only a fraction of the living or once-living organisms of interest. Many species are difficult to study in isolation because they fail to grow in laboratory culture, depend on other organisms for critical processes, or have become extinct. Methods that are based on DNA sequencing circumvent these obstacles, as DNA can be isolated directly from living or dead cells in various contexts. Such methods have led to the emergence of a new field, which is referred to as metagenomics. * DNA sequencing can provide insights into organisms that are difficult to study because they are inaccessible by conventional methods such as laboratory culture. Examples are for instance, organisms that exist only in tight association with other organisms, including various obligate symbionts and pathogens, members of natural microbial consortia and an extinct cave bear. * Isolation and sequencing of DNA from mixed communities of organisms (metagenomics) has revealed surprising insights into diversity and evolution. * Partially assembled or unassembled genomic sequence from complex microbial communities has revealed the existence of novel and environment-specific genes. The application of high-throughput shotgun sequencing environmental samples has recently provided global views of those communities not obtainable from 16S rRNA or BAC clone– sequencing surveys. The sequence data have also posed challenges to genome assembly, which suggests that complex communities will demand enormous sequencing expenditure for the assembly of even the most predominant members. However, for metagenomic data, this complete assembly may not always be necessary or feasible. Determining the proteins encoded by a community, rather than the types of organisms producing them, suggests a means to distinguish samples on the basis of the functions selected for by the local environment and reveals insights into features of that environment. For instance, Examination of higher order processes reveals known differences in energy production (e.g., photosynthesis in the oligotrophic waters of the Sargasso Sea and starch and sucrose metabolism in soil) or population density and interspecies communication, overrepresentation of conjugation systems, plasmids, and antibiotic biosynthesis in soil (Fig. 4, lower left). The predicted metaproteome, based on fragmented sequence data, is sufficient to identify functional fingerprints that can provide insight into the environments from which microbial communities originate. Information derived from extension of the comparative metagenomic analyses performed here could be used to predict features of the sampled environments such as energy sources or even pollution levels. Metagenomics data bases are currently been set up: for instance http://www.megx.net/index.php?navi=EasyGenomes EXAMPLE G. VENTER SARGASSO SEA Boston (04/16/04)—This Spring, J. Craig Venter is sailing around the French Polynesian Islands scooping up bucketfuls (figuratively) of seawater in an ambitious voyage to sample microbial Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 22 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) genomes found in the world's oceans. His 95-foot yacht, Sorcerer II, has been outfitted with all manner of technical equipment to accommodate the task, as well as a few surfboards should that opportunity arise. Venter and colleagues report finding 1.2 million genes, including almost 70,000 entirely novel genes, from an estimated 1,800 genomic species, including 148 novel bacterial phylotypes. This diversity is staggering and to a large extent unexpected. "We chose the Sargasso seas because it was supposed to be a marine desert," says Venter wryly. "The assumption was low diversity there because of the extremely low nutrients." His team sequenced a total of 1.045 billion base pairs of non-redundant sequence. At the height of the work, "over 100 million letters of genetic code were sequenced every 24 hours." The results have been deposited in GenBank. You can go and search for them. PALEOGENOMICS Mammoth genome A very recent application is the use of metagenomics approaches to sequence the mammoth genome: Usually mitochondrial genomes are sequenced form extinct species as it is abundantly present in eukaryotic cells and thus easier to sequence. In permafrost settings, theoretical calculations predict DNA fragment survival up to 1 million years (11, 12). When preserved in such conditions sequencing of genomic DNA is still possible. 1 g of bone was used to extract DNA which was subsequently used for library construction and sequencing technology that recently became available (13, 19). The mammalian fraction dominated the identifiable fraction of the metagenome. Nonvertebrate eukaryotic and prokaryotic species occur at approximately equal ratios, with paucity of fungal species and nematodes. hits against grass species to outnumber the ones from Brassicales by a ratio of 3:1, which could be indicative of ancient pastures on which the mammoth is believed to have grazed. From Poinar et al., Science 2006. Ancient salt crystals Bacteria have been found associated with a variety of ancient samples, however few studies are generally accepted due to questions about sample quality and contamination. Cano and Borucki isolated in 1995 a strain of Bacillus sphaericus from an extinct bee trapped in 25-30 million-yearold amber. More recently a report about the isolation of a 250 million-year-old halotolerant bacterium from a primary salt crystal has been published. Halite crystals from the dissolution pipe Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 23 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) at the 569 m level of the Salado Formation were taken from sampling. A fluid volume of 9 l was recovered from an inclusion in the crystal and inoculated into two different media: casein-derived amino acids medium (CAS) and glycerol-acetate medium (GA). Only the CAS enrichment yielded the bacteria, designated 2-9-3. Once isolated the bacteria, the next step in the research is to achieve its taxonomical classification. Two important genotypic markers widely used in recent bacterial taxonomy are the 16S rRNA gene sequence data and DNA-DNA hybridization data. Many researchers reported the correlation between 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity values and genomic DNA relatedness. It has been proposed that phenotypically related bacterial strains showing 70% or greater genomic DNA relatedness constitute a single bacterial species. In contrast, those having <70% but >20% similarity are considered to be different species within a genus. These analysis showed that the organism was most similar to Bacillus marismortui (99% similarity S) and Virgibacillus pantothenticus (97.5% S). Phylogenetic analysis showed that isolate 2-9-3 is part of a distinct lineage within the larger Bacillus cluster. Additional info Metagenomics and industrial applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005 Jun;3(6):510-6. Review. The metagenomics of soil. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005 Jun;3(6):470-8. Review. http://www.megx.net/index.php?navi=EasyGenomes http://www.bio-itworld.com/news/041604_report4889.html 1.7. 1.7.1 Functional genomics & Systems Biology Systems biology Is field that originated in the early 90’s: it stems from ‘molecular biology’ but reflects a novel holistic way of thinking: understanding complex biological phenomena in their entirety. In systems biology a cell is considered as a system that interacts with its environment. It receives dynamically changing environmental cues and transduces these signals into the observed behavior (phenotype or dynamically changing physiological responses). This signal transduction is mediated by the regulatory network (below). Genetic entities (proteins), located on top of a regulation cascade, are activated by external cues. They further transduce the signal downstream in the cascade via proteinprotein interactions, chemical modifications of intermediate proteins, etc into transcriptional activation and subsequent translation. Ultimately, these processes turn the genetic code into functional entities, the proteins. The action of regulatory networks determines how well cells can react or adapt to novel conditions. This signaling network in a cell can be compared with the electronic circuitry on a microchip. It also consists of individual components (often called modules). Systems biology is the science that tries to decode the design principles of biological systems. It can be used for both fundamental and applied purposes. A typical example of a fundamental application is the domain of evolutionary systems biology which has as a goal studying the impact of network rewiring on adaptive behavior and organism evolution. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 24 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Figure: The cell as a signal transduction system. The signaling circuitry can be considered as having a modular composition, in which each part form an individual functional unit. 1.7.2 Synthetic biology from an engineering point of view: rational design The major difference between ‘genetic engineering/biotechnology’ to ‘synthetic biology’ would reflect a novel mind set: the idea of rational design. Synthetic biology relies on the identification, reuse or adaptation of existing parts of systems to construct reduced systems tailored to an aim whose starting assumptions might be very different from those of the natural system. The idea of using parts stems from the parallel between electronic circuits and biological systems. Each component of the system can be seen as an individual transistor. By combining the different signaling components a circuitry can be designed that has operational characteristics or that gives rise to functionalities which do not occur as such in nature. The premise of synthetic biology is thus built on the modularity of signal transduction pathways. This modularity thus allows constructing and synthesizing artificial biological systems by combining “microchip design principles” with libraries of molecular modules to obtain a desired microbial functionality. According to this vision, Synthetic Biology should be able to rely on a list of standardized parts (amino acids, bases, proteins, genes, circuits, cells, etc) whose properties have been characterized quantitatively and on software modeling tools that would help putting parts together to create a new biological function. The idea behind the MIT ‘Registry of Standard Biological Parts’ (http://parts.mit.edu), is that as more libraries of parts are being constructed and provided that all these parts are well documented and standardized, in the end one can select immediately his appropriate part from the library and the tedious step of making a mutant library or synthesizing all possible sequences and characterizing their in and output characteristics can be omitted. Currently the Registry is a collection of ~3200 genetic parts that can be mixed and matched to build synthetic biology devices and systems. Founded in 2003 at MIT, the Registry is part of the Synthetic Biology community's efforts to make biology easier to engineer. It provides a resource of available genetic parts to iGEM teams and academic labs. Current challenges in synthetic biology: The premise of synthetic biology is built on the modularity of signal transduction pathways. Artificial biological systems are synthesized by combining parts with desired functionalities and kinetic behavior, as predicted by a model-based design. However the generation of the parts with the proper characteristics is still very laborious and ad hoc (large libraries are made randomly, see figure below. All parts within such library need to be characterized experimentally). A fundamental systems understanding of how regulation or a certain kinetic behavior is encoded could further rationalize the design of modules and contribute to a better standardization (that is the key features in the primary sequence that drive a specific expression behavior, motifs, motif spacing, nucleosome positioning, etc). Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 25 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) Modeling is the key to both systems and synthetic biology (see figure below). For systems biology modeling aims at getting a fundamental understanding of the host cellular behavior, while for synthetic biology ‘model-based design’ is used to determine the circuit topology and its parameters subject to predefined design requirements. Such design requirements should not only consider desired input/output characteristics (linear, oscillating behavior, bistability), but also take into account the easiness by which certain parts can be manipulated in the lab. A challenging task is making design models that determine design parameters conditioned on systems properties of the global cellular system. Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 26 Introduction Bioinformatics (Bachelor Cel & Gen/ Biochemistry) HETEROGENEOUS EXPERIMENTAL DATA SOURCES HOW WILL WE ANALYZE THE DATA SIMULTANEOUSLY? Kathleen Marchal Dept of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics UGent/ M2S KU Leuven 27