Excerpts from “The Great Bone Hoax:

advertisement

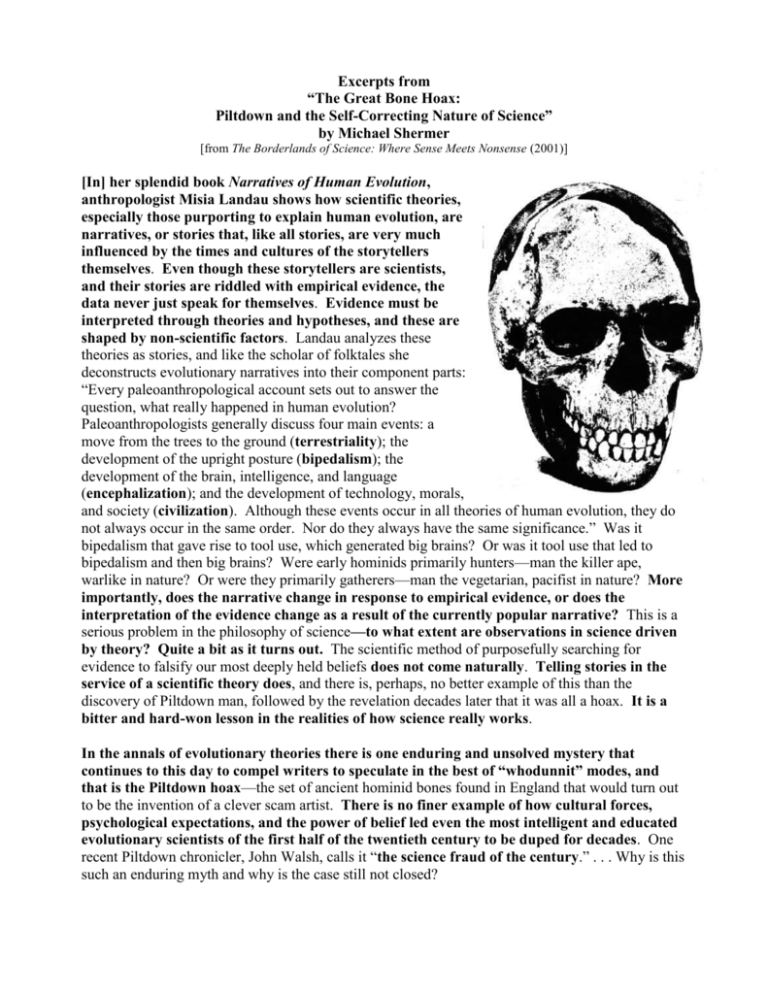

Excerpts from “The Great Bone Hoax: Piltdown and the Self-Correcting Nature of Science” by Michael Shermer [from The Borderlands of Science: Where Sense Meets Nonsense (2001)] [In] her splendid book Narratives of Human Evolution, anthropologist Misia Landau shows how scientific theories, especially those purporting to explain human evolution, are narratives, or stories that, like all stories, are very much influenced by the times and cultures of the storytellers themselves. Even though these storytellers are scientists, and their stories are riddled with empirical evidence, the data never just speak for themselves. Evidence must be interpreted through theories and hypotheses, and these are shaped by non-scientific factors. Landau analyzes these theories as stories, and like the scholar of folktales she deconstructs evolutionary narratives into their component parts: “Every paleoanthropological account sets out to answer the question, what really happened in human evolution? Paleoanthropologists generally discuss four main events: a move from the trees to the ground (terrestriality); the development of the upright posture (bipedalism); the development of the brain, intelligence, and language (encephalization); and the development of technology, morals, and society (civilization). Although these events occur in all theories of human evolution, they do not always occur in the same order. Nor do they always have the same significance.” Was it bipedalism that gave rise to tool use, which generated big brains? Or was it tool use that led to bipedalism and then big brains? Were early hominids primarily hunters—man the killer ape, warlike in nature? Or were they primarily gatherers—man the vegetarian, pacifist in nature? More importantly, does the narrative change in response to empirical evidence, or does the interpretation of the evidence change as a result of the currently popular narrative? This is a serious problem in the philosophy of science—to what extent are observations in science driven by theory? Quite a bit as it turns out. The scientific method of purposefully searching for evidence to falsify our most deeply held beliefs does not come naturally. Telling stories in the service of a scientific theory does, and there is, perhaps, no better example of this than the discovery of Piltdown man, followed by the revelation decades later that it was all a hoax. It is a bitter and hard-won lesson in the realities of how science really works. In the annals of evolutionary theories there is one enduring and unsolved mystery that continues to this day to compel writers to speculate in the best of “whodunnit” modes, and that is the Piltdown hoax—the set of ancient hominid bones found in England that would turn out to be the invention of a clever scam artist. There is no finer example of how cultural forces, psychological expectations, and the power of belief led even the most intelligent and educated evolutionary scientists of the first half of the twentieth century to be duped for decades. One recent Piltdown chronicler, John Walsh, calls it “the science fraud of the century.” . . . Why is this such an enduring myth and why is the case still not closed? As a narrative story, the Piltdown discovery—a big brain atop an apelike jaw—fit the scientific and cultural expectations of the day in that it conveniently supported the prevailing theory . . . that humans first evolved a big brain and only later such features as bipedalism and tool use. Afterall, it was argued, it was our singular ability to think in abstract ways, to plot and strategize and communicate complex ideas, that allowed us, in this progressivist model, to take the great leap forward in evolution above and beyond our simian ancestors. Their bodies may have been similar, but their brains were not. Exceptional encephalization was what set us apart. Further, since it was believed that the most advanced races of today (white) can be found in northern climes (Europe and Asia), fossils of our ancestors would most likely be found here, and certainly not Africa . . . Indeed, out of Germany came a treasure trove of fossils, starting with the breathtaking finds from the valley of Neander [in 1856], giving the name to the most famous of all our ancestors [i.e., “Neanderthal Man”]. Out of France [in 1869] came our most recent and advanced relatives, the Cro-Magnons, with their cave paintings, clothing, jewelry, and complex tool kits that allowed them to develop what could genuinely be called culture. Additional fossils were discovered in Holland, Belgium, and scattered areas of Asia and Southeast Asia, including significant finds at Peking (“Peking Man”) in China and at Java (“Java Man”) in southeast Asia. It seemed everyone was getting in on the great human fossil hunt; everyone except the English, that is. Was it possible that humans did not evolve in England? Were Englishmen nothing more than a recent migration from the continent, a backwater of human evolution? If only an ancient hominid could be found here. And what a coup it would be that if that hominid, unlike many of the finds coming from elsewhere, clearly showed a humanlike brain sitting atop more primitive primate features, especially a jaw. Seek and ye shall find, build it and they will come—pick your metaphor. The British got what they were wishing for in 1912. On February 15, 1912, a British lawyer named Charles Dawson, who devoted every moment of his spare time to amateur archaeology, presented to the renowned Keeper of Geology of the British Museum of Natural History, Arthur Smith Woodward, several cranial fragments that appeared to be of an ancient hominid. Dawson told Smith Woodward that in 1908 workmen had unearthed fragments from a gravel pit at Piltdown in Sussex [in southern England], accidentally smashing them with their pick. The skull fragments were modern in appearance, with a large, thick casing, yet they were found in deep, ancient layers, indicating great antiquity. On June 2, 1912, Smith Woodward, Dawson, and a youthful paleontologist and Jesuit priest named Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, . . . went to the pit to continue the dig. There Dawson made another find—the lower jaw of the skull, including two molars, very ape-like in structure but indicating humanlike wear. Additional digging uncovered stone tools, chipped bones, and fossil animal teeth that placed the ancient hominid well back in evolutionary history. The December 5, 1912 edition of the most respected British science journal, Nature, ran a short news item of the find: Remains of a human skull and mandible, considered to belong to the early Pleistocene period, have been discovered by Mr. Charles Dawson in a gravel-deposit in the basin of the River Ouse, north of Lewes, Sussex. Much interest has been aroused in the specimen owing to the exactitude with which its geological age is said to have been fixed. On December 8, 1912, Dawson, under the auspices and endorsement of Smith Woodward, announced his great find at the meeting of the Geological Society of London. A few skeptics voiced their doubts, but one of the crucial pieces of evidence that might have addressed their concerns—the jaw—was mysteriously (and conveniently as it turns out), broken in just the right places to preclude resolution. In its December 19, 1912 edition, Nature ratched up the excitement by proclaiming this as the singular find in the history of British paleontology: “The fossil human skull and mandible to be described by Mr. Charles Dawson and Dr. Arthur Smith Woodward at the Geological Society as we go to press is the most important discovery of its kind hitherto made in England . . .” The authors went on to explain just why this specimen was so important: “At least one very low type of man with a high forehead was therefore in existence in western Europe long before the low-browed Neanderthal man became widely spread in this region. Dr. Smith Woodward accordingly inclines to the theory that the Neanderthal race was a degenerate offspring of early man and probably became extinct, while surviving modern man may have arisen directly from the primitive sources of which the Piltdown skull provides the first discovered evidence.” Newspaper headlines soon followed. On December 19, the Times of London announced: A PALEOLITHIC SKULL FIRST EVIDENCE OF A NEW HUMAN TYPE The New York Times followed suit, identifying the deeper, theoretical issues involved in the find: PALEOLITHIC SKULL IS A MISSING LINK MAN HAD REASON BEFORE HE SPOKE DARWIN’S THEORY IS PROVED TRUE . . . That summer Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, with a background in paleontology and completing his theological training at a Jesuit seminary, conveniently (some say suspiciously) near Piltdown, found an apelike lower canine tooth, but worn in a very humanlike fashion. The following summer, as the great nations of Europe cascaded toward their destiny of total war, Dawson added to the trove a fossilized thigh bone from an elephant and what appeared to be a stone tool, and a fairly advanced one at that. In 1915, at another pit two miles from Piltdown, Dawson uncovered two more hominid skull pieces along with another tooth similar to previous finds. Now there could be no doubt as to both the authenticity and the significance of the fossil collection, and for four decades the finds when largely unchallenged. Humans evolved not only in Europe and Asia, but in England too, and these ancient hominids first evolved big brains then the other hominid features, as evidenced by the Piltdown fossils, cementing the progressivist narrative plot: big brains bipedalism tool use . . . The scientific world was ecstatic that this new find had confirmed what they always believed must be true about human evolution—our large brain had lifted us above our simian ancestors. And it was an Englishman no less, no trivial matter in this jingoistic era on the eve of the Great War where France and Germany had already produced a number of fossils attesting to their role in humanity’s rise out of the detritus. It was too good to be true. Unfortunately for those who allowed their skeptical facilities to be overcome by cultural expectations . . . it was too good to be true. In 1953, scientists Kenneth Oakley, J. S. Weiner, and W. E. le Gros Clark announced that new dating techniques had proven the skull fragments to be of modern origin, as was the orangutan jaw, all stained, chipped, and filed to look ancient. The flint artifacts were worked with modern tools, the fossil animal teeth were from locals elsewhere, and everything was carefully placed in the Piltdown pit. It was all a hoax—four decades worth! [308-313] Regardless of the solution to this unsolved mystery, Piltdown provides two valuable lessons in the nature of science: 1. Science is subject to bias. The head of the Institute for Creation Research, Duane T. Gish, wrote of Piltdown in 1978 that “The success of this monumental hoax served to demonstrate that scientists, just like everyone else, are very prone to find what they are looking for.” Well, sure, that much is true; but this is the very reason that science is constructed to be selfcorrecting. It has built into it methods to detect not only hoaxes, but both conscious and unconscious biases. This is what sets science apart from all other knowledge systems and intellectual disciplines. If it were not for this self-correcting mechanism, in fact, science could not have made the remarkable progress it has over its 500-year history. Its greatest weakness, in fact, is its greatest strength. 2. Science is self-correcting. It is critical to emphasize that in the Piltdown hoax, as with all other scientific hoaxes and errors, it was scientists who exposed the hoax and science that corrected the mistake and moved forward with more and better research . . . Still, Piltdown is a painful reminder of the fact that intelligence and education is no prophylactic [i.e., protection] against fraud and flimflam. In Piltdown we saw some of the most highly decorated and respected scientists in the world taken in by someone who was at most an amateur hoaxer. It shows that humans are pattern-seeking, storytelling animals, who seek and find patterns that fit a meaningful story. Once the pattern is found and a story developed around that pattern, additional confirming evidence (or clues of a hoax) are ignored . . . Piltdown shows that scientists—even world-class scientists—are not immune. [317319] Further Reading: The Piltdown Conspiracy (1983), by Stephen Jay Gould Piltdown Man (BBC: Archaeology) Piltdown Man is revealed as fake (PBS: Science Odyssey) 1) Why were the Piltdown fossil finds of the 1910s considered important, especially to many Englishmen? 2) How does the Piltdown Man hoax illustrate that scientists are influenced by both internal & external considerations? How did it, as Shermer claims, “fit with the scientific and cultural expectations of the day”? 3) What does the story of the Piltdown Man, according to Shermer, illustrate about the nature of science and scientists? Do you agree or disagree with Shermer? Explain.