[41] See Footnote 37

advertisement

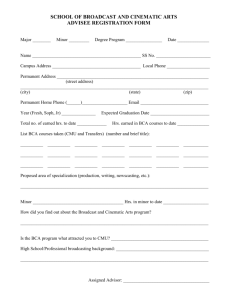

![[41] See Footnote 37](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007782072_2-1574a5f0bed3492e62ed7f90f5675890-768x994.png)