Inquiry Project - Appalachian State University

Reading Workshop 1

READING WORKSHOP

Introduction

During the summer, I took Literature and Language Arts Integration through

Appalachian University. A portion of the class dealt with allowing students to choose what they read during class and not just during free reading. The teacher instructs through a mini-lesson and then students read their chosen books, applying the minilesson to what they are reading. The teacher conferences, verbally or written, to see if the students are able to apply the teaching to the text. I wanted to try this Reading Workshop approach with my fourth and fifth grade students.

This is my third year as a Reading Specialist in the elementary school teaching kindergarten through fifth grade. I have twelve small groups of students for 25 to 30 minutes daily. All my students are below grade level in reading and many do not like to read because they are not good at it. Most of them struggle with comprehension as well as reading fluently.

My goal is to keep my students interested and motivated so that they will want to read, want to read better, and be able to understand what they read. As I learned more about Reading

Workshop, I felt this would be a good program for my older students and that I could adapt the format into a 30 minute class.

Comprehension is the end goal of most reading instruction because the purpose of reallife reading is to understand and process the text. A reader integrates motivation and cognition when he picks a book, reads it, comprehends it, and lets it affect his mental/emotional state

(Guthrie, McGough, Bennett, & Rice, 1996). For students to acquire comprehension skills and reading strategies they must put forth a large amount of effort and be motivated. Motivated students usually want to understand the text and think about the information (Guthrie, Wigfield,

Reading Workshop 2

Barbosa, Perencevich, Taboada, Davis, Scafiddi, & Tonks, 2004). To develop comprehension,

Guthrie et al. (2004) theorizes that (a) engagement relates to interaction with the text,

(b) engaged reading is needed to understand the material, (c) cognitive strategies and motivation can be enhanced through instruction, and (d) a teacher that integrates motivation and cognitive strategies will improve student reading and comprehension skills. Because engagement and motivation are part of reading comprehension, ways to motivate students need to be included into the daily language arts lesson.

In The Book Whisperer, Miller (2009) writes that students need to be able to choose what they read to motivate and interest them. Struggling readers need instruction in reading/comprehension strategies and they need to spend time reading text if they are going to become strong readers. They need this independent reading time to practice the skills they are learning. The more students read, the more it will become a daily habit (Miller, 2009). When students read independently, they are able to experience the full act of reading (Moss & Young,

2010). Morrow (1992) found in a study on the attitudes of second graders from minority backgrounds that the children thought reading was fun and enjoyable when they got to choose what to read and choose comfortable surroundings. Reading Workshop is a way to instruct, motivate, choose, and conference.

Action Research Question

Will Reading Workshop, using minilessons and choice of book, improve students’ motivation and comprehension?

Participants

Cornatzer Elementary School, where I teach, is in the Davie County School System, in

Mocksville, North Carolina. It is a K-5 Title I school with 54% of students on free or reduced

Reading Workshop 3 lunch. There are about 435 students in this rural community school. The participants in my research were four fourth grade students: one boy and three girls. The daily class time was

30 minutes and I conducted my research for eight weeks.

Instructional Procedures

Reading Workshop traditionally includes minilessons, individual reading, conferencing, and sharing (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001). My adapted Reading Workshop has these same components. I begin with a minilesson about a literary element or skill such as inference. I read aloud a picture book and we apply the skill to the story. The students write the skill, definition, picture book title, and example of the skill from the picture book in their composition books.

The topics for minilessons come from the North Carolina Standard Course of Study, EOG preparation, and needs that I see arise (Atwell, 1998). Then the children choose a book that is

“just right” for them and one they want to read. By letting students choose what they want to read, they become more involved in their learning (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001). To teach students to take charge of their own learning is part of the New Teacher Evaluation. When students find topics that interest them, they want to know more and thus choose to read more on the subject

(Ivey, 2010). During independent reading, they may stay seated or go to a comfortable spot in the room. Independent reading is not “free reading” or “sustained silent reading” rather it is a time for instructional conversations with students. I go to the students individually and have them tell me about what they are reading and give me examples of the skills that we studied. I do not have genre requirements for independent reading because the class time is only 30 minutes. Reading Workshop is more like real life reading (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001) and having my students be able to understand real life reading is my goal.

Reading Workshop 4

Another component of Reading Workshop is guided reading. Since I only have the students for 30 minutes a day, I set aside a week or two for guided reading. I select the text, an interesting novel, a selection from an anthology, or a nonfiction book that correlates with what is being studied in the fourth grade. Using the same text, we work as a group to learn reading strategies and literary elements. Students share, verbally or written, how the strategies apply to the guided reading text (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001).

Data Collection

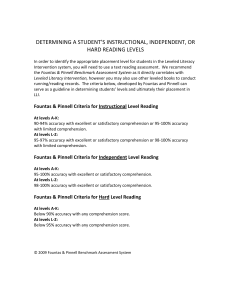

At the beginning of the study, I gave my fourth grade participants the “Garfield

Elementary Reading Attitude Survey” (McKennna & Kear, 1990) to compare their interests and motivation to read. This survey has questions about academic and recreational reading. Each question has four answer choices that are pictures of Garfield: happy Garfield, slightly smiling

Garfield, mildly upset Garfield, and very upset Garfield (Figure 1). The students circle their answers. I administered the Garfield Survey again at the end of November.

Figure 1

To measure comprehension I used the STAR Reader, computer software that assesses reading levels through cloze passages. The STAR was given to the students at the beginning of the school year and I administered the assessment again at the end of November.

Results

The Reading Workshop format has been good for my students. They seem to enjoy it because it gives them flexibility and chose. I am pleased with how they are able to apply the

Reading Workshop 5 minilessons in their independent reading and guided reading. The children write the skill or literary element that we are learning on a card and then give an example (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 Student Examples

Reading Workshop 6

According to the “Garfield Elementary Reading Attitude Survey”, the students averaged an increase of nine percentage points from the beginning of the study to the end. This indicates that the students enjoy reading recreationally and academically more now than they did in

September.

Three of the students’ instruction reading levels increased using data from STAR Reader.

Normal growth would be one-tenth per month or three-tenths since the beginning of the year.

Instructional

Reading Level

Students Aug. Nov. Difference

IG 3.8 3.7

OM 2.9 3.2

OS

SL

2.7

3.0

3.8

3.4

- .1

+ .3

+1.1

+ .4

Table 3

One student, OM, made normal growth in her reading level. SL made four months growth and

OS made eleven months growth. I am not sure why IG decreased in her reading level. An interesting comparison is the student whose reading level increased the most is also the student whose attitude survey increased the most. Of course, this is what the research said, if students are motivated to read they will comprehend.

Conclusion

These results suggest that Reading Workshop is an effective instructional program for comprehension and for motivating struggling readers. Two of the four children achieved more than normal growth and that is what below-grade-level students must do to catch-up to grade level. Although I did not include a group of six fifth graders in the study, I used the Reading

Reading Workshop 7

Workshop format with their class. This group has been very excited about choosing independent reading books and many of them have asked to take the books home to finish. This shows interest and motivation.

As I was doing research for this paper, I learned more about Reading Workshop and ways to improve my instruction. I received new ideas for minilessons and questions to ask during student/teacher conferencing. I did not expect any of the students to decline in their reading level, but working with struggling readers is a challenge. They do not progress or improve at a normal rate. Before doing the research, I did not think about students assuming responsibility for their own learning through Reading Workshop. Helping students become independent learners is one of my goals in the New Teacher Evaluation.

Eight weeks is not enough time to evaluate Reading Workshop, but I have seen enough improvement and interest to continue this format. One thing that I will change is the guided reading. I am not going to choose another long novel. With only 30 minutes a day, it takes a long time to get through some fourth grade novels. Instead, I will use shorter texts for guided reading and this will leave more time for independent reading. Reading Workshop is a good instructional program to improve students’ motivation and comprehension.

Reading Workshop 8

References

Atwell, N. (1998). In the middle.

Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. Su. (2001). Guiding readers and writers. Portmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

Guthrie, J. T., McGough, K., Bennett, L., Rice, M. E. (1996). Concept-oriented reading instruction: An integrated curriculum to develop motivations and strategies for reading.

In Baker, L., Afflerbach, P., & Reinking, D. (Eds.), Developing engaged readers in school and home communities (pp. 165-188) . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Barbosa, P., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Davis, M. H.,

Scafiddi, N. T., & Tonks, S. (2004). Increasing reading comprehension and engagement through concept-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96,

403-423.

Ivey, G. (2010). Texts that matter. Educational Leadership, 18-23.

McKenna, M. C. & Kear, D. J. (1990). Measuring attitude toward reading: A new tool for teachers. The Reading Teacher, 43, 626-629.

Miller, D. (2009). The book whisperer. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Morrow, L. M. (1992). The impact of a literature-based program on literacy achievement, use of literature, and attitudes of children from minority backgrounds. Reading Research

Quarterly, 27, 250-275.

Moses, B., Young, T. A. (2010). Creating lifelong readers through independent reading.

Newark, DE: International Reading Association.