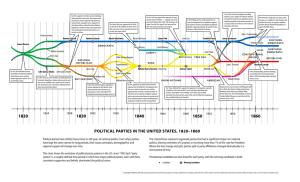

Rise of Popular Politics 1820-1830: Second Party System

advertisement

The Rise of Popular Politics, 1820-1830 Although the beginning of the nineteenth century saw Jeffersonian Republicans seeking to limit the size and power of the federal government, this trend had to yield to the realities of a growing nation; simply relying on states to deal with their own issues was not enough. With the purchase of Louisiana in 1803, the U.S. expanded dramatically—almost doubling the size of the country. Additionally, the U.S. victory in the War of 1812 renewed the American confidence in their independence from Britain and in the establishment of a stronger, more capable defense for the new nation. Social change was also taking place at a rapid pace. European observers, like Alexis de Tocqueville, came to the U.S. during the first decades of the new century to watch and write about the “American Democratic Revolution.” In his book, Democracy in America (1835), Tocqueville wrote about the decline of the American intellectual elite as government leaders and their middle-class, workingmen replacements. This rise of a new group of elected leaders would give rise to the Second Party System in the U.S., with a focus on a more democratic republic. This focus would include: General culture of egalitarianism (sense of equality among certain groups) o Social and religious origins of some equality o Ideal of equal opportunity (“American Dream”) No monarchy or hereditary power (power passed down from father to son) More social, economic, and political interactions across classes Expansion of the franchise, or the right to vote, was symbolic of the American Democratic Revolution. It was only after large masses of (white) men with “election fever” pushed for the right to vote was this made possible in most states. Many states even re-wrote their constitutions to include voting and representation by district and mandating popular elections of public officials. With their newfound power, some politicians turned to the parties to advance their religious or cultural agendas (plans) upon the public, often causing controversies over liberty and equality (i.e., the Benevolent Reformers). Other politicians used the increase in eligible voters to their own advantage. Bribes for votes, government assistance for private businesses, fraudulent trades of stock, and political allies became an unfortunate part of the new party system. Part of this party system was the advent of the political machine, named after the fact that parties managed their members like a well-designed textile loom, a machine that “wove the diverse interests of various social and economic groups into…a coherent legislative program.” The key to any good political party is not just to influence law, but to get your party members elected to influence law in various legislative (lawmaking) roles. One politician particularly adept at this was Martin Van Buren, who rejected the idea that political parties (then called factions, like in the Federalist Papers) were dangerous to a democratic republic. Van Buren rose into New York political elite with the aid of his supporters, the “Bucktails,” and his political machine, the Albany Regency. In 1821, he used a system of patronage, or the buying of support/votes to control the New York legislature. He built additional support with the creation of secretive party meetings called caucuses (now referring to closed, but not secret, party meetings). Although the “Era of Good Feelings” was built on a sense of nationalism, the Second Party System found its roots in sectionalism, concentrating their membership bases in certain sections of the country. By 1824, the Democratic-Republican Party had broken up into warring sectional groups, all vying for political and economic power. Instead of one Republican candidate in the election of 1824, there were four, each representing a section of the country: William Crawford (South), John Quincy Adams (New England), Henry Clay (West), and Andrew Jackson (West). The War of 1812 had undermined the ability of Indians in the Northwestern Territory to protect themselves from white settlers, and along with the invasion (and annexation) of Florida in 1823, raised General Andrew Jackson to such prominence that he won the popular, if not the electoral, vote in 1824. This upset the one-party rule of the Era. Jackson received more popular and electoral votes than any other candidate, but not the constitutionally mandated majority of electoral votes. This threw the election to the House, where Henry Clay's support of John Quincy Adams led to his election. Jackson's supporters, the “Jacksonians,” believing their candidate deserved the presidency, were enraged when he lost and became even angrier when Adams named Clay his secretary of state. The outrage expressed at what they called a "corrupt bargain" haunted Adams throughout his tenure. Unlike his term as Secretary of State, where conservative values and rigid morals followed the previous political era, and success with the acquisition of Florida, John Quincy Adams's term of office was largely a failure. The National Republicans, led by John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster, believed that government power should be used to advance a wide range of social and cultural improvements. Adams proposed an elaborate program of internal improvements that included traditional projects such as roads, canals, and harbors, as well as more innovative ideas such as a national university and government support for scientific research. Other National Republicans argued that government authority should be used to advance moral reforms such as temperance. This faction of National Republicans, soon to become a fullfledged party known as the Whigs, maintained something of the Federalists' earlier confidence in the benefits of an active national government. In fact, the Whigs drew most of their support from the northeast, just as the Federalists had in earlier decades. But there was a more middle-class orientation to the Whig agenda. It was less narrowly focused on economics on a grand scale and more focused on using government power to improve and "moralize" the quality of life in America's communities. For example, Whigs believed that public institutions like schools, hospitals, and asylums could elevate the character and improve the health of the public. The Jacksonian Democratic-Republicans insisted that they were the true heirs of the Jeffersonian Republican tradition—but to emphasize their commitment to advancing the interests of the common man, they soon simplified their name to Democrats. These Democrats favored a smaller national government and opposed, in particular, any Whig proposal that seemed to threaten their economic, social, or cultural freedoms. They viewed the Whigs as self-righteous meddlers, and they argued that, historically, federal intervention in the economy served only small economic elite. Democrats did, however, encourage forcible government removal of Native Americans in order to open western lands to white migrants. And Democrats did support war with Mexico in the 1840s in order to expand the western domain. The Democrats controlled the presidency during most of this second party era and succeeded in advancing most of their major policy ambitions. Ninety-thousand Indians were moved out of the eastern states, the national boundaries dramatically expanded through war with Mexico, the institutional centerpiece of the Federalist era—the Bank of the United States—was destroyed, and America's public lands were made more accessible to common farmers. But during the 1850s, the issue of slavery shattered the existing political alignments and led to the emergence of a third era in American political history. QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER: 1. EXPLAIN how the growth of political parties led to a growth in democracy. 2. DESCRIBE the key reasons for the development of the Second Party system. 3. COMPARE and CONTRAST the Whig Party to the former Federalist Party. 4. COMPARE and CONTRAST the Democratic Party to the former Democratic-Republicans. Sources: America’s History; http://online-history.org/US1.htm and http://www.shmoop.com/political-parties/the-first-party-system.html