THIS IS THE TITLE PAGE OF THE THESIS

advertisement

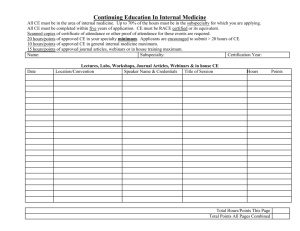

MONEY, FRIENDS OR FIT: FACTORS INFLUENCING CAREER SELECTION DECISIONS IN MEDICINE Pri Shah & John Bechara Carlson School of Management University of Minnesota Monica Drefahl, Joseph Kolars, Barbara Spurrier, Douglas Wood & Nicholas LaRusso Department of Internal Medicine Mayo Clinic 1 Money, Friends or Fit: Factors Influencing Career Selection Decisions in Medicine ABSTRACT This study investigates the role of job characteristics (income & lifestyle), exposure, person-environment fit, and network actors on career selection decisions in medicine. Personenvironment fit is defined as the degree to which physicians perceive their personality, problem solving style, skills, interests, norms and values as similar to that of physicians in different medical specialties. Network actors were defined as friends, role models, and mentors. A field study was conducted in the internal medicine department of a large Midwestern Academic Medical Center. Residents were asked to report their experiences and perceptions on all of the eleven different subspecialties from which they could choose as well as their final selection decision. Thus, we have a record of each subject’s experience and perception for both their chosen subspecialty as well the ten subspecialties they opted not to select. The results indicate that career selection decisions are significantly influenced by physicians’ perceptions of fit, the presence of network actors and prior exposure, even when controlling for job characteristics. Keywords: Career selection; person-environment fit; social network; healthcare 2 Money, Friends or Fit: Factors Influencing Career Selection Decisions in Medicine Career selection decisions in medicine impact both the individual physician and the composition of the physician workforce. Thus, understanding the factors that influence physicians’ career choice is critical to understanding the distribution of the physician workforce and its ability to serve the needs of the U.S. population. Medical researchers investigating career trends have focused on the role of specialty attributes (i.e., lifestyle, income, work hours, training requirements) and individual attributes (gender, age, debt, personality factors) on career choice decisions (Barshes, Vavra, Miller, Brunicardi, Goss & Sweeney, 2004; Dorsey, Jarjoura, Rutecki, 2003; Newton & Grayson, 2003). The findings indicate that both factors are important; however, they are often investigated independently, thus it is unclear which factors actually drive career choice decisions. Additionally, the role of social factors and the fit between subspecialty factors and individual attributes is neglected. Thus, we draw from the person-environment fit and social network literature to provide a more comprehensive perspective on career selection decisions in medicine. Additionally, the medical context contributes to our understanding of organizational behavior and specifically career selection decisions. The medical context provides an ideal research environment for several reasons. First, subjects are confronted with the same choice set during their pre-selection period. Although, exposure to each option in the choice set differs among subjects, they still have the same set of options available for their final selections. This allows us to control for non-observable characteristics when estimating the effects of observable characteristics of the selected option and the non-selected options. Second, subjects adhere to the same strict schedule during the pre-selection period. This also allows us to control for 3 unobservable environmental characteristics. Finally, subjects have a large degree of discretion in their choice but are also constrained by the same match process. This allows us to ascertain, albeit imperfectly, the volitional and discretionary aspect assumed in career selection but rarely corroborated in the literature (Fouad, 2007). By providing natural controls to test the effects of person-environment fit and social networks, we can corroborate or falsify the findings in the career selection literature. The person-environment fit literature finds that congruence between the person and the environment is predictive of positive outcomes for both the individual and the organization (Chapman, Uggerslev, Carroll, Piasentin & Jones, 2005; Chatman, 1991; Kulick, Oldham & Hackman, 1987). We extend these findings to suggest that perceptions of fit will also influence job choice decisions. Prior researchers have examined the role of fit on job selection; however, the results are mixed. We suggest that this may be due to artifacts in the research design. Prior research attempting to link person-environment fit to job selection relies on respondents who have already selected a job within a given firm; thus the degree of fit reported may be biased or constrained within the data set. We also incorporate a social network perspective into our investigation of career selection decisions. Decisions are not made devoid of social context. Individuals are inherent social information processors and their behaviors, attitudes and actions are often influenced by others around them particularly under conditions of uncertainty (Shah, 1998; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). In fact, social network researchers have found that the influence of friends and similar others is more dominant than objective characteristics when making organizational choice decisions (Kilduff, 1990). Choosing a profession, one of the most important decisions made by a 4 physician, is often one fraught with uncertainty (West al. 2006). Thus, investigating the role of network actors such as mentors, role models, and friends is particularly germane in this context. The contributions of this study for medicine are two fold. First, the simultaneous examination of specialty attributes, social factors and person-environment fit will provide us with a more comprehensive understanding of the drivers of job choice in medicine. Second, the study provides certain policy implications for the academic medical institutions as they grapple with subspecialty shortages. Next, the contributions of this study for the career selection literature are twofold. First, this study extends the boundaries of person-organization fit by showing the impact of fit on individual outcomes might precede organizational entry and effect career selection decisions. Second, the comparative evaluation of the effects of fit and social networks on career selection provides two complementary views of the same phenomenon from two relatively insular bodies of literature. THE ROLE OF PERSON-ENVIRONMENT FIT IN CAREER CHOICE DECISIONS In this study, we define person-environment fit as the congruence between individual skills, interests, norms, values and attributes (i.e., personality styles, learning styles & interpersonal styles), and the requirements and opportunities provided by the work environment. This multidimensional view of person-environment fit is consistent with prior research that often delineates four different domains of fit: person-vocation fit; person-job fit; person-organization fit and person-group fit (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006). Person-vocation fit stems from the early work in this discipline on vocational choice by Holland (1985) and suggests a self selection matching process when individuals select careers. Person-job fit is defined as the relationship between an individual’s skills, abilities and motivations and those required by a specific job (Kulick, et al., 1987; Kristof, 1996). Person-organization fit focuses on the congruence of norms 5 and values between the individual and the organization (Chatman, 1991; O’Reilly, Chatman & Caldwell, 1991). Person-group fit recognizes that individuals are not socially isolated when performing their work duties and incorporates interpersonal compatibility with coworkers as a component of fit (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006). Although much of past research investigates one component of fit, we suggest that a more holistic view of fit more accurately represents the embeddedness of interactions that occur at work (Granovetter, 1985). Researchers investigating multiple components of fit simultaneously find that that they each have important and independent effects on work satisfaction (Kristof-Brown, Jansen & Colbert, 2002) In general, the findings for fit indicate positive individual and organizational outcomes. Early research on fit using the job characteristics theory finds that individuals are better suited for jobs when their motives, skills and needs match those required by the job (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). Work on vocational choice finds that people are more attracted to careers based on their interests, values and personalities (Holland, 1985). Research on fit and individual outcomes find that person-organization fit is associated with positive work attitudes, performance, well being, and low stress (Bowe, Ledford & Nathan, 1991; Chapman et al., 2005, Chatman, 1991; Kristoff & Brown et al, 2002; O’Reilly et al., 1991; Resick, Baltes & WalkerShantz; 2007). Research on fit and organizational outcomes finds that person-organizational fit is associated with higher organizational commitment and lower turnover intentions and lower turnover. (Chatman, 1991; O’Reilly et al., 1991). In contrast a lack of fit is associated with decreased performance, dissatisfaction and greater stress (Pervin, 1968). Researchers investigating fit and job choice find that although fit is predictive of organizational attraction and intentions to accept a job, its impact on job choice are mixed (Chapman et. al., 2005; Kristoff Brown et al., 2002; Resick et. al., 2007). Sociologists have 6 found that newspaper reporters are more likely to apply for jobs at conservative or liberal outlets depending on their own personal predilections (Sigelman, 1975). However, a recent metaanalysis examining applicant attraction to organizations and job choice decisions finds that although person-job fit predicts acceptance intentions, it did not govern actual job choice (Chapman et al., 2005). Similarly, Cable and Judge (1997) and Resick et. al. (2007) find a weak effect for person-organizational fit and job selection decisions. Research design constraints are often cited as factors in attenuating the effect of fit and job choice. Specifically, most studies recruit subjects from within a given organization. Since only applicants who received jobs are in the subject pool, range restrictions in person-organization fit may be a factor. This is due to the fact that applicants are often offered positions due to perceptions of fit (Chatman, 1991); they may self-select out due to perceived lack of fit (Chapman et al., 2005) or may be offered alternatives of better fit (Resnick et al., 2007). Additionally, since job choice requires a commitment from both the applicant and the employer, and there are often fewer jobs than candidates the relationship between job choice and fit will likely be mitigated (Chapman et al., 2005). Thus, although the body of work on person-environment fit intuitively leads us to surmise that fit will play a critical role in job selection decisions, evidence supporting this claim is weak. To conclusively investigate the relationship between person-environment fit one must survey respondents on both jobs that were selected jobs as well as those that were not selected. Thus, residency programs, where all subjects select from the same potential specialty choices, provide an exemplar setting to expand our understanding of the person-environment fit as it relates to actual job selection decisions. Medical researchers have already begin to suggest that fit with regards to personality, lifestyle, intellectual challenge or clinical skills may be an important 7 factor in specialty selection decisions (Burack, Irby, Carline, Ambrozy, Ellsbury & Stritter, 1997), but fit has yet to be measured directly. An alternative explanation for non-significant relationship between fit and job choice may be limited exposure. Job candidates may have minimal prior contact with incumbent firm members. Lack of fit may be due to the lack of knowledge of potential areas of fit. While person-organization fit may predict outcomes such as satisfaction and commitment once in the firm, it may not predict job choice when the knowledge of fit is limited. Past research findings indicate that spending time with incumbent members of the firm prior to entry is predictive of person-organizational fit upon entry into the organization (Chatman, 1991). Thus, prior exposure to a firm or job will likely be positively related to job choice decisions. Research findings in primary care support this premise. The findings indicate that greater exposure to family practice in the form of a family practice clerkship, or assignment to a curriculum that emphasized primary care and long-term community based placements, increased the likelihood of selecting that specialty (Bland, Meurer & Maldonado, 1995; Kaufman et al., 1989). Unfortunately, the timing of selection decisions in medicine may limit the amount of exposure physicians have to their range of options. In effect, internal medicine residents are required to make a subspecialty selection decision in the beginning of their second year of residency when they may not have yet rotated in all the different subspecialties. Thus, prior exposure may be a critical factor in job selection decisions in this setting. The discussion above leads to the following predictions for the influence of prior exposure and person-environment fit on career selection decisions. 8 Hypothesis 1. Prior exposure to a specialty will influence career choice, such that physicians are more likely to select subspecialties in which they have had prior experience even when controlling for income and lifestyle attributes of that specialty. Hypothesis 2. Perceptions of fit will influence career choice, such that physicians are more likely to select specialties in which they perceive greater degrees of fit even when controlling for income and lifestyle attributes of that specialty. THE ROLE OF NETWORK ACTORS IN CAREER CHOICE DECISIONS Choosing a profession is a defining moment in the career of a physician. It simultaneously opens up new opportunities but closes off others; thus, activating feelings of uncertainty. Research on the durability of career decisions finds that 62% of the internal medicine residents change their career plans at least once during the course of their residency (West, Popkave, Schultz, Weinberger & Kolars, 2006). Additionally, two-thirds of the first and second year residents indicate that they are uncomfortable making an informed selection decision in their second year (Smith, Feit & Mueller, 1997). Yet, due to the constraints of the match process, these residents are asked to make their final selections early in the second year of their three year residency, when they may only have limited exposure to their range of options. Organizational behavior literature suggests that it is under these conditions that network actors will thrive as agents of influence. Social information processing research and social comparison research find that reliance on social cues is particularly strong under conditions of uncertainty. Employees are more likely to rely on social cues from others to help them evaluate aspects of their job such as performance, compensation, career trajectory and work duties in 9 efforts to mitigate the uncertainty (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978; Festinger, 1954; Goodman, 1977). Of course, not all social cues are equally influential. Social network research advances social comparison and social information processing research by further delineating both the type of social cues that are of greatest impact and their mechanism of influence (Shah, 1998; Shah 2000). Network theory provides a perspective where individuals are embedded in a web of relationships with other actors who in turn influence, facilitate and constrain behavior. The network actors of interest in this study are friends, mentors and role models, for each is known to play an influential role in the career selection process. Friendship channels are particularly conducive to social influence because the frequency, intensity, and proximity of interaction among friends results in a greater exchange of information and a greater opportunity to transmit social cues (Rice & Aydin, 1991). This direct interaction results in socially constructed perceptions that are similar (Ibarra & Andrews, 1993). Friendship ties also tend to be stable, strong and enduring. Thus, the strength of friendship ties, their source credibility and the conformity pressure that results amplifies the influence exchanged through this channel. Similarly, group research also finds that the limited exposure to information and restricted contact in social groups results in common evaluations. Members of cohesive groups are more likely to exhibit greater behavior conformity than less cohesive groups primarily due to the group’s ability to reward appropriate actions and punish deviance (Levine & Moreland, 1990; Guzzo & Shea, 1992). Researchers investigating organizational selection decisions have found support for the influence of friends. In a study of the interview patterns of MBA students, Kilduff (1990) found that students who were friends were likely to interview with the same organizations even when controlling for similarities in job preferences and academic concentrations. Given the degree of uncertainty associated with selecting a profession, it is 10 expected that physicians’ decisions to select a specialty will be influenced by those of their friends. Mentors and role models are also network actors that play a critical role when individuals select a profession. Mentors are defined as individuals who are experienced in a given profession and take an active interest in an individual’s career development in that profession. They provide support, advice, guidance and encouragement to individuals to help them pursue a given path. Mentoring is often associated with facilitating career selection in medicine (Sambunjak, Straus, & Marusic, 2006). Specifically, researchers have found support for the role of mentors at all levels of medicine, from residency selection decisions, subspecialty selection decisions, and even decisions to pursue academic medicine in general (Osborn, 1993; Rubeck et al., 1995). A role model is a reference person that individuals use for comparison for they occupy a position that the individual aspires towards. It describes people who are admired for they serve as exemplars of positive behavior. Research on specialty choice decisions in medicine finds ample support for the importance of role models on career selection decisions (Ambrozy, Irby, Bowen, Burack, Carline & Stritter, 1997; Osborn, 1993; Wright, Wong, & Newill, 1997). The discussion above suggests that given the uncertainty associated with selecting a subspecialty and the importance of network actors in conditions of uncertainty, that network actors will have a greater impact on career selection decisions than subspecialty attributes. Hypothesis 3. The presence of network actors (i.e., friends, mentors, role models) in a specialty will influence career selection decisions such that physicians are more likely to select subspecialties in which there is a greater presence of network actors even when controlling for lifestyle and income attributes of that specialty. 11 METHODS Our primary source of data for this study comes from a large Midwestern Academic Medical Center, which we will refer to as WFMC. WFMC is an integrated and not-for-profit group practice with more than 3300 physicians, scientists and researchers, and 46000 health staff. Research Site This study is conducted in the Internal Medicine Department of WFMC. An internal medicine residency program consists of three years of additional training upon completing medical school. It is an apprenticeship program where residents are subject to long hours and rigorous training. Training is comprised of rotations through the different areas within internal medicine; thus, residents have exposure to an assortment of subspecialties. Upon completing their internal medicine training, residents can opt to practice General Internal Medicine or pursue further training into one of ten different subspecialties: Allergy, Cardiology, Endocrine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Infectious Diseases, Nephrology, Preventative Medicine, Pulmonary and Rheumatology. Thus, residents can select one of eleven options when making their career selection decisions.1 Although subspecialty training does not commence until after completion of a residency program; subspecialty selection decisions must be made early in the residency program due to the constraints of the match process. The match process is a mutual selection process where residents and fellowship programs enter their rank order of preferences into a database by a 1 Although there is no additional training to select General Internal Medicine as an option, we have opted to consider it as a distinct career option on par with the ten sub specialties. After interviewing physicians in General Medicine and residents who have selected the area became clear that the selection process for General Internal Medicine was similar to that of the sub specialties in internal medicine. 12 given date. A computerized algorhythm is used to determine optimal matches between the two parties’ preferences. The match process occurs at the end of the second year of residency; however, interview season begins as early as 18 months into the residency and actual application process starts as early as twelve months into the program. Thus, residency training may be three years, but in actuality, residents only have 1 year to determine their subspecialty selection decisions. Additionally, much of their rotation schedule for the first year is already predetermined by the residency program prior to the start of their residency. This site and setting have numerous advantages for examining our research questions. First, testing our hypothesis in a single organization allows for controls in confounding factors such as variations in organizational structure, culture, services and programs. On the other hand, the internal medicine program, being the largest program at WFMC with 150 residents and 11 distinct choices, provides a natural and meaningful variability in the type of residencies, average salary and average work hours all of which are important factors in the career selection process. Each of the eleven areas is represented by a corresponding division within the department of internal medicine. Divisions are independent entities with variations in the type medicine practiced, culture and composition. Finally, the uncertainty in career decisions during the residency program in internal medicine (West, et. al., 2006) provides an exemplary setting to study the decision-making process for career selection decisions. Procedure A two stage research design was used in this study. In the first stage we conducted semi structured interviews with 10 graduating residents to assess key factors in career decisions. We conducted an extensive review of the literature and found 40 different items related to selection decisions. Subjects were asked to think about why they selected their subspecialty, and were 13 give a set of cards listing each item. They were then asked to sort the cards in one of three categories based on whether they were important, somewhat important or not at all important in their selection decision. Subjects were also given blank card to write in other alternative reasons, but none were reported. Upon completing the card sort for their selected specialty, subjects were then asked to think of all the other subspecialties that were not selected. They were then given a set of the same 40 items as the first task, but this time the items were negatively worded. Subjects were again asked to sort the 40 negatively worded cards into three categories based on which were the most important, somewhat important or not at all important in their decision not to choose the other subspecialties. The interview results revealed that the most important factors driving subspecialty decisions were skill fit (interest in patients & patient problems), personality fit, favorable rotation experience, prior exposure, and the presence of a mentor. Factors not considered important were mostly demographic (age, grades, gender, martial status), and subspecialty attributes (income, prestige, years of training, malpractice potential). When residents were asked why they did not select the other subspecialties, lack of fit was the primary answer (lack of culture fit, skill fit, personality fit). Lack of a role model was also a top indicator of non selection decisions. The results of the interviews were used to construct the survey questions for primary data collection in stage two. Data Collection The survey was collected over a period of three months (October 2007 – December 2007). We opted for a pencil and paper survey since it provided residents with an alternative to the numerous web-based surveys they receive per week, and provided them with a $10 coffee card as a reward for completing the survey. The response rate for the survey was 41%, 62 of the 150 residents completed our survey. Respondents were primarily male (70%), married (64%) 14 and under the age of 30 (82%). Respondents were equally distributed across all three years of the program, 26% were first year residents, 34% were second year residents, 34% were third year residents and 6% were chief residents (fourth year residents who serve as advisors and administrators). Finally, 85% of respondents had selected a subspecialty (N=1 for Allergy; N=21 for Cardiology; N=3 for Endocrine; N=10 for Gastroenterology; N=5 for General Medicine; N=6 for Hematology; N=1 for Infectious Diseases; N=2 for Nephrology; N=5 for Pulmonary). Cardiology and Gastroenterology were the most popular subspecialties representing 39% and 19% of our subjects’ choices respectively. In order to assess possible selection bias, we examined the representativeness of the respondents with the study population. Selective response bias was evaluated by comparing difference in gender and residency year between respondents and non-respondents. The analysis was restricted to gender and residency year since those were the only relevant variables that the WFMC maintained in their records. Univariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the odds of being a non-responder given the variables (gender and residency year). Responders were defined as the dependent variable (non-responders coded 1 and responders coded 0) and, gender and residency year were the independent variables. The results showed no statistically significant relationship between the dependent variables and the independent variables and hence no significant selection bias. Item non-response bias was studied to test a hypothetical assumption that there is no difference between residents that have selected an option compared to those who have not selected an option. This assumption is important given that the analysis will be conducted on the sample of residents that have made a career selection decision and hence generalizing the results across all individuals that responded might be more complex if the assumption doesn’t hold. 15 Univariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the odds of not having made a career decision given a set of independent variables (level of debt, age, gender, and residency year). Responders that have not yet made a career decision were defined as the dependent variable and were coded 1 and 0 otherwise. The results showed that married residents without children were more likely to have selected an option than those who were single or those who had children. On the other hand, male residents, residents with higher levels of debt, and not surprisingly, resident more advanced in their program (second and third year residents) were more likely to have selected an option. Hence, generalizing the results of the subsequent analysis require consideration of the level of debt, age, and gender of the respondents. Finally, the assumption underlying choice models is that decision-makers have discretion in selecting their preferred option (Fouad, 2007). In order to ascertain this assumption, we compared the selected option with the highest ranked option. If the selected option was consistent with the highest ranked option, we concluded that the decision-maker had a choice in the selection process. From the sample of resident only two residents had inconsistent results and hence were removed from the sample. These residents selected hematology and pulmonary, respectively, but ranked cardiology as their highest option. Measures Dependent Variable. Our primary dependent variable of Selection Decision was obtained on the survey instrument. Residents were asked if they had selected an option and which area they had selected. The selection measure that we employed is a variable that takes a value of 1 for the option that the resident selects and zero for the remaining ten options. This measure is consistent with measures used in discrete choice models (McFadden, 1974) where individual decision-making behavior is examined when facing a choice set with nominal 16 alternatives. In our case the choice set consists of the eleven distinct options reported above. Our secondary variable is Rank Decision. Rank Decision is based on three items. The first items asked residents to check all other (i.e. other than the selected option) options that they were considering. The second item asked residents to rate on a scale of 1 to 5 how seriously they were considering them (1=not at all to 5=very seriously), and the third item asked them to rank order their preferences for each of the options (1=most preferred to 11=least preferred). Using these items, this measure was coded using the top 3 options since the median number of other options under serious consideration was 2. The remaining options were coded a unit-rank lower that the third ranked option, and the incomplete options (i.e., options where the subjects had neglected to provide a rank) were coded a unit-rank lower than the remaining options. This coding scheme provides a way to mitigate problems with the reliability of coefficients due to decreases in ranking information as the ranking decreases (Hausman & Ruud, 1987). This measure is also consistent with measures used in rank ordered models (Beggs, Cardell, & Hausman, 1981; Chapman & Staelin, 1982). Independent Variables. We used the survey results to develop scales for Fit and Network Actors. Residents were asked a series of questions about their past experiences and perceptions for each of the eleven different options. This measure of perceived fit provides a more proximal account and direct assessment for the residents’ conception of personenvironment fit (Cable & DeRue, 2002). This measure is consistent with interaction psychology that construes people’s decisions as a function of their own perception of fit with their environment (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). We performed a factor analysis on these items using principle components analysis with a varimax rotation. The results revealed two distinct factors with eigen values greater than 1. The specific items and their factor loadings are provided in 17 table 1. The first factor contains 9 items that measure Fit. This measure reflects the degree to which residents perceived fit between their personality, problem solving styles, norms, values and skills with those of the physicians in each option. The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1) to “strongly agree (5) or N/A if not applicable. The resulting Fit measure is the mean across all items within the factor. The Cronbach alpha for Fit is 0.90. Network Actors was reflected in the second factor by 4 items. The items loading on this factor include three items directly measuring the presence of friends, mentors and role models in each subspecialty, as well as an item measuring communication frequency with members of the different options. The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1) to “strongly agree (5) or N/A if not applicable. The resulting Network Actors measure is the mean across all items within the factor. The cronbach alpha for Network Actors was 0.83. Prior Exposure was measured using a single item in the survey that asked respondents if they had exposure to each of the options in medical school. The item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1) to “strongly agree (5) or N/A if not applicable. ---------------------------------Insert Table 1 about here ---------------------------------Control Variables To account for alternative explanations we included control variables for two key job attributes found to impact career decisions in medicine: Income and Controllability of Life Style. The Income variable consists of the average salary for each subspecialty based on the 18 figures in the 2007 physician compensation survey by the American Medical Group Association. We scaled the variable to the $10,000. Controllability of lifestyle is defined as “personal time free of practice requirements for leisure, family, and avocational pursuits and control of total weekly hours spent on professional responsibilities.” Put differently, it refers to the amount of time remaining for activities independent of medical practice. Perceptions of controllable lifestyle have been shown to account for most of the variability in the changing trends in the specialty choices of graduating US medical students (Dorsey et. al., 2003). To examine the controllability of lifestyle we use average work hours. We obtained average work hours for each option from the American Medical Association Frieda website for residents. This website provides descriptive information for each of the different options one of which is average work hours. RESULTS The data in the first two tables provides a descriptive backdrop for the overall results. Descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables are listed in table 2. Table 3 illustrates the mean differences for the variables on the options selected compared to those that were not selected. Residents reported a greater degree of fit, more network actors, and greater prior exposure to selected options (means= 4.37, 4.51, 3.67 respectively) compared to those they did not select (means = 3.28, 2.77, 3.17 respectively). Selection options were also higher in income, work hours (means=312,316.07, 53.01, respectively) when compared to the non selected options (means=250,359.55, 50.20, respectively). To further examine the role of different networks actors on career selection decisions we looked at a few of the items that constituted network ties separately. Specifically, we wanted to determine whether residents indicated that they had more mentors, role models and friends in the 19 options that they selected compared to those that were not selected. We dichotomized the answers to these three questions such that 1-3 was coded as 0 (no mentors, role models or friends; 1=strongly disagree to 3 =neither agree nor disagree) and 4-5 was coded as 1 (had a mentor, role model or friend; 4=agree & 5=strongly agree). The results indicated our subjects reported having a mentor in the option that they selected 96% of the time compared to only 31 % of the time in those that they did not select. Subjects reported having a role model in their selected option 100% of the time compared to 37% of the time in those that were not selected. Finally, subjects reported friends in their selected option 88% of the time compared to 46% of the time in those that were not selected. ---------------------------------------- Insert Table 2 & 3 about here ---------------------------------------- Similar to the method used by Shaver and Flyer (2000) for location choice, we apply a conditional logit (McFadden, 1974) to test the hypotheses. This method is suitable for data on career choice when we have data on the attributes of the selected option and all other options in the choice set. In our case, the choice set contains 11 distinct options and the predictors reflect objective measures of each option’s attributes (income, average work hours and satisfaction) and perceived option preferences (fit, network actors, and prior exposure). The method estimates how changes in option attributes increase or decrease the probably that a resident will select a particular option. Applying the conditional logit to career selection is done as follows. Let nit be the expected preference i for selecting option t. Residents select the option with the greatest expected preference which can be represented as follows: nit = pXit + Sit 20 The vector of unknown parameters is β and the vector of option j attributes for observation n is xjn. εit refers to the random disturbances due to unobservable characteristics of the options and any deviant or non-optimal behavior on the part of the resident. Finally, assuming ε is a Type I error, we can represent the probability that option j is the highest preference (Yi) using a logit: Pn(Yi = t) = exp(β'xit) ∑exp(β' J xit) t= j The independent variables consist of prior exposure, fit and network actors. The control variables consist of income and average work hours. We begin modeling the career selection model by estimating the effects of the control variables. We then include the independent variables prior exposure, fit and network actors to test each hypothesis. We conclude by including all the independent variables in the final model. If a coefficient is positive and significant then an increase in the value of the variable would increase the probability that a resident selects that particular option. If a coefficient is negative and significant then an increase in the value of the variable would decrease the probability that a resident selects that particular option. The effects of the control variables on selection decision are in column 1 of table 4. All the control variables are positive and significant. This suggests that an increase in income and average work hours will increase the probability that a resident selects that particular option. However, the coefficient of income is greater than the coefficient of work hours suggesting that it has a greater impact on career selection. Although the income result is consistent with prior research, the work hours result runs counter to the existing work on controllability of lifestyle (Dorsey et. al, 2003). 21 The effects of prior exposure on selection decision are in column 2 of table 4. The results support hypothesis 1 that prior exposure to a particular option in medical school increases the probability of selecting that option even when controlling for attributes of the option. In fact, the results show that prior exposure is an even stronger predictor of selection decision than income. The effects of fit on career selection are in column 3 of table 4. The results also clearly support hypothesis 2, that perceived fit influences selection decisions. Fit also appears to play a stronger role in selection decisions than income. Next, the effects of network actors on selection decisions are in column 4 of table 4. The results support hypothesis 3, that network actors influence career selection. Similar to the prior results, the network actors play a stronger role in selection decisions than income. Finally, the effects of prior exposure, fit and network actors are shown in column 5 of table 4. The results support hypothesis 2 and hypothesis 3, illustrating that network actors such as mentors, role models and friends, and fit influence career choice. The coefficients of fit and network actors suggest that fit is a much more influential factor in determining the selection decisions than network actors, or income. In order to control for other possible option differences that might affect option preferences we use an option fixed-effects specification. We restrict the choice set to options that have been selected at least once as a requirement for the fixed-effects estimation (we dropped 2 options: preventative medicine and rheumatology). Once again, the results support hypothesis 2 and 3. Hence, fit and network actors remain significant after controlling for other specialty factors. ---------------------------------Insert Table 4 about here ---------------------------------- 22 The analysis above investigates residents’ selection decisions in a full set of eleven options. Although, the subjects do indeed have eleven options, not all may be considered seriously when selecting a future career. In fact, residents may only seriously consider a small subset of options. Thus, testing our hypotheses using only those options that were seriously considered may provide a more conservative test of critical selection factors driving career selection decisions. To pursue this line of investigation we first examined how many options residents selected when asked which other subspecialties they were considering and then examined how seriously they were considered. On average, residents considered 2.29 other options (median =2), and options that were checked were considered far more seriously than those that were not checked (means=3.50 & 1.17 respectively). In fact, analysis of the rank order data for the options indicates that the first three choices were considered most seriously (means =3.10 & 3.30, 2.75 respectively for the first, second and third ranked options), while those ranked higher were not regarded as serious options (means range from 2.11 for the fourth ranked option to 1.04 for the eleventh ranked option). Thus, we decided to conduct additional analysis using the Rank Decision variables. As mentioned earlier, this measure was coded using the residents’ perceptions of their top 3 options that were under serious consideration. The remaining options were coded a unit-rank lower than the third ranked option, and the incompletes were coded unit-rank lower than the remaining options. For example, a resident ranked cardiology, pulmonary and rheumatology as her top 3 choices (coded 11, 10, 9 respectively) while the remaining options were coded a unit-rank lower than rheumatology (coded 8), and the incompletes were coded a unit-rank lower than the remaining options (coded 7). The results are robust to changes in coding as long as the difference in coding is a unit-rank. 23 To estimate the models with ranking data, we apply a rank ordered logit (Beggs, Cardell, & Hausman, 1981; Chapman & Staelin, 1982). This method is suitable for data on options ranking where we have data on the attributes of the selected options and other options in the choice set. Similar to the conditional logit, the choice set contains 11 distinct options and the predictors reflect objective measures of option attributes (income, average work hours and satisfaction) and perceived option preferences (fit, network actors, and prior exposure). This ranking of the 11 options is assumed to be sequential where the highest-ranked option is chosen over all the other options, the second-ranked option is chosen above the remaining option with the exception of the highest-ranked option, and so forth. The model assumes that the selection behavior underlying each rank position satisfies the independence from irrelevant alternatives assumptions (IIA) where the alternatives in our case are the options. Hence, the choice probabilities are: J-1 P(1,2,...,J) = ∏P(j/ j , j + 1,...,J) j=1 Here P(1,2,...,J) is the probability of observing the rank order of option 1 being preferred over option 2, option 2 preferred over option 3, and so forth. Additionally, if the probability of ranking a given option assuming a multinomial logit (MNL) model and that all the options follow the same logit model, the probabilities of observing the rank-order is: Pn(1,2,...,J / β) = ∏ J j=1 ∑ exp( β ' xi ) The vector of unknown parameters is fi and the vector of subspecialty j attributes for observation n is xjn. Hence, the rank ordered logit model is similar to estimating (J -1) independent multinomial logit models. Finally, the model assumes that choice process is similar 24 each rank in the ranking process. However, it has been shown that the reliability of the ranking information decreases as the ranking decreasing (Hausman & Ruud, 1987). In order to mitigate problems with reliability of the ranking information we resorted to the aforementioned coding that focuses on the top 3 options. Similar to the modeling process used for the conditional logit models, we first estimate the effects of the control variables income and average work hours. We include the independent variables prior exposure, fit and network actors to test each hypothesis. We conclude by including all the independent variables in the final model. In a rank ordered model, if a coefficient is positive and significant then an increase in the value of the variable increases the probability of ranking that option higher than the remaining options in the choice set. Conversely, if a coefficient is negative and significant then an increase in the value of that variable decreases the probability of ranking that option higher than the alternative options remaining in the choice set. The results of the rank ordered logit are in table 5. The results are consistent with those of the conditional logit with the exception of the effects of income. As fit and network actors are included in the model, the effect of income is insignificant suggesting a possible mediating effect. The remaining results support hypothesis 2 and hypothesis 3, even when controlling for the other option characteristics using the fixed-effects specification. ---------------------------------Insert Table 5 about here ---------------------------------Finally, we examined if our data violated the independence from irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumption for the conditional logit and the rank ordered logit. However, the Haussmann- 25 McFadden test and the Small-Hsiao test provide inconsistent results. This is not surprising given that Cheng and Long (2005) have shown that such test have poor small sample size properties. They conclude that such tests are not useful for assessing violation of the IIA assumption and suggest going back to McFadden’s (1974) suggestion that the conditional logit (similarly for the rank ordered logit) should be used only where the alternatives “can plausibly be assumed to be distinct and weighted independently in the eyes of each decision maker”. Based on this suggestion, we have no doubt that the distinctions between all options in the choice set are very significant even for non-physicians. Each of the eleven options work on different organs or systems, manage different patient problems or diseases, and each have their own professional associations, board certification exams, journals and conferences. Overall the conditional logit and the rank ordered logit analyses support our hypotheses that prior exposure, fit and network actors are influential factors in residents’ selection process even when controlling for option attributes such as income or lifestyle. DISCUSSION The results of this study provide strong support for the influence of prior exposure, fit and network actors on career selection decisions in medicine. Overall, the findings indicate that although attributes such as income and average work hours are important indicators of choice, it is the fit between the attributes and individual preferences that serves as the primary driver of selection decisions. In the case of the conditional logit, the results do support the existing literature suggesting that income is key variable in selection decisions. Although not the main driver, income was a significant factor in the equation even when examining our independent variables. Interestingly, the results did not support the prior work on controllability of lifestyle, 26 as our average work hours variable was significant in the opposite direction. Specifically, residents tended to select career options with longer rather than shorter work hours. The results of the exposure variable are interesting for it suggests that simply having prior experience in a subspecialty has the ability to influence selection decisions even more so than the potential income of the different subspecialties. Given that the results for exposure were not significant when fit and network actors were added into the equation, we suspect that the effect of prior exposure may be mediated by fit and network actors. A mediation perspective for prior exposure is consistent with prior research finding that prior exposure was related to fit (Chatman, 1991). The results demonstrate strong support for the importance of social factors in career selection decisions. Friends, mentors, role models, and even those with whom we have frequent communication influence selection decisions. The role of mentors and role models is consistent with prior findings in the medical literature (Sambunjak et al., 2006). The direct guidance, wisdom and exposure to the profession provided by mentors and indirect observations and emulations of role models are both clearly important in selection decisions. In fact, many studies in medicine and our own interview sample suggest that residents recognize the importance of these two types of actors. Less intuitive is the influence of friends and communication partners. Although the social network literature finds strong support for the influence of friends on individuals’ attitudes, behaviors and actions; the medical literature does not examine the role of these types of network actors. Furthermore, when we asked residents directly whether their decisions were influenced by those of their friends, all of the subjects in our interview sample indicated that friends were definitely not a factor in their decisions. Interestingly, network research suggests just the opposite. The residency program creates an opportunity where there is 27 frequent interaction with peers often over long durations of time (i.e., nights on call). Given the amount of interaction that occurs with friends, and the uncertainty associated with subspecialty selection decisions, fellowship selection is a context in which social cues from friends will likely dominate. In the future, it would be interesting to determine whether some network actors had more influence than others. Not all social cues are created equal. Different actors have the ability to influence on different dimensions (Shah, 1998; 2000). Unfortunately, given that all four of our network actor measures loaded on one factor, we are not able to fine tune our understanding of the role of different network actors on career selection decisions. The strongest result of this study was that of fit. Perceptions of fit on interests, skills, personality style, problem solving style, interpersonal styles, norms and values clearly dominated the selection process. Although medical researchers have discussed the importance of fit; to date, researchers have not investigated it directly. Additionally, person-environment fit research in organizational behavior has suggested that fit will play a role in selection decisions, but the evidence has been weak. Given that our study examines residents’ perceptions and experiences in both selected and non-selected subspecialties, we are clearly able to illustrate the importance of fit in career selection decisions. In this study we take a multidimensional view of fit; however, given the results of our factor analysis we are unable to separate the different types of fit. Thus, it is not clear whether type of fit (person-job fit, person-organization fit or person-group fit) has a differential impact on career selection or whether we should call into question the separate effects of each type of fit on career selection. For the time being we adopt the latter and suggest that in the future determining 28 whether different components of fit have a differential or similar impact on career decisions might provide an interesting contribution to the career selection literature. THEORETICAL IMPLCIATIONS The theoretical implications of this project are three fold. First, the results call into question the separate effects of the underlying dimensions of fit on career selection decisions. It might be that different types of fit have similar effects on career selection in contrast to the results in the literature on individual outcomes such as job satisfaction and strain (Kristof-Brown et. al. 2005). Second, the findings of the study extend the boundary conditions of the personenvironment fit literature. The findings to date focus on the individual and organizational benefits of fit once employees are in an organization. The findings of our study demonstrate that fit is important even prior to organizational entry and can actually impact selection decisions. Finally, although past research has found extrinsic components of the profession such as income and lifestyle to be predictors of selection decisions, our findings indicate that once fit, network factors or even prior exposure are taken into account that they play a limited role in selection decisions. Thus, income and lifestyle may be important when they are examined in isolation, but once social factors, experience, fit and network actors are incorporated, lifestyle no longer becomes a factor. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS Understanding how physicians make career choice decisions has important implications for the field of medicine and physician career satisfaction. First, the results suggest that subspecialty attributes such as income and average work hours play a limited role in career selection decisions. Thus, attempts to influence the balance of subspecialties via compensation methods or job restructuring are unlikely to be successful. Instead, the results suggest that 29 altering factors related to fit, network actors and prior exposure is more likely to influence career choice. Specifically, fellowship directors facing decreased applicants in their area may want to create greater opportunities for exposure for residents and medical students to their subspecialties. The findings indicate that greater exposure may result in greater perceptions of fit and more opportunity for social interaction, and thus subsequently influence decisions. Alternatively, the network variable results suggest that formalizing a mentor program or creating greater channels of communication among physicians in an under represented subspecialty may influence selection decisions. Second, the findings from the person-environment fit literature indicate that fit is predictive of many positive employee outcomes such as higher performance, greater satisfaction and lower stress. Thus, fellowship directors may be well suited to encourage a greater exploration and discovery of the different professions so that residents select those that fit them best. LIMITATIONS & FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH The limits of our study suggest interesting areas for future research. The primary limitation of this study is due to its cross sectional design. Subjects in our sample reported on their perceptions of fit after they had already decided upon a subspecialty. To take precautions against recall biases, we structured the survey such that the fit questions preceded the choice question. However, once a choice is known, perceptions of fit may be greater. Future research using a longitudinal design would help alleviate this concern. Specifically, if residents were surveyed at the end of each of their rotations about their perceptions of fit, perceptions would not be influenced by actual decisions. Research findings do indicate that many residents have already decided upon subspecialty prior to the start of their residency; however, it is likely the recall bias would be minimized within this design. Alternatively, future research on residency 30 selection decisions by medical students may be less prone to recall bias since most make their final choices in their third or early part of your fourth year (Kassenbaum & Szenas, 1995). Use of actual fit measures rather than perceptions of fit also provide an interesting direction for future research. Matching actual values or preferences of physicians in the different subspecialties with those of residents may provide more robust findings for fit. Lastly, the results of the exposure variable were quite interesting. Simply having prior experience in a subspecialty resulted in a greater likelihood to select that area. This raises some interesting questions regarding dynamics of this variable. Specifically, does the duration or timing of the exposure matter? Findings from the decision making research suggest primacy and recency biases in judgments. Thus, future research should investigate the influence of rotation patterns and duration to fully understand how prior experience influences career choice decisions. 31 TABLES: Table 1: Factor Loadings of Principle Component Analysis Using Varimax Rotation Items for each subspecialty Fit 1. I am interested in the types of patient problems in this subspecialty 2. I was treated well in my subspecialty rotation in this subspecialty 3. My skills are well suited for this subspecialty 4. My norms and values are consistent with the culture of this subspecialty 5. My personality fits well with that of the physicians in this subspecialty 6. I felt comfortable working with the staff on the rotation of this subspecialty 7. The physicians in this subspecialty approach problem solving the same way that I do 8. The staff in this subspecialty were more like me than in other subspecialties The staff in this subspecialty seemed satisfied with their careers 9 10. I had a mentor in this subspecialty (someone who took active interest in me and helped me learn the values, and ways of thinking and acting in this subspecialty I 11. had a role model in this subspecialty (someone who I observed informally to help me understand the values, and way of thinking and acting in this subspecialty 12. I frequently communicate with members of that subspecialty 13. I have many friends and acquaintances in this subspecialty Table 2: Descriptive Statistics Variable | Mean --------------3.3 1.Fit 2.9 2.Network Actors 3.3 3.Prior Exposure 50.4 4.Average Work Hours 25.6 5.Average Salary and Correlation between Variables sd 1 2 3 + ---------------0.79 1.0000 1.0000 1.07 0.6726* 0.5420* 1.0000 1.36 0.5090* 0.4322* 0.4046* 1.0000 6.10 0.2630* 0.2142* 0.1190* 0.0299 5.94 0.1805* *p<0.05 32 0.6196 0.7129 0.6952 0.6081 0.7445 0.7453 0.6737 0.7523 0.6720 0.3295 Network Actors 0.4216 0.1007 0.4391 0.3815 0.3508 0.2800 0.4409 0.3592 0.0684 0.6983 0.3995 0.7091 0.1699 0.2253 0.8477 0.7493 1.0000 TABLE 3: Mean differences between Selected & Non Selected Subspecialties Variable Selected Subspecialty Non Selected Subspecialty N=57 Mean (sd) N=570 Mean (sd) FIT Network Actors Prior Exposure Average Work Hours Average Salary 4.37 4.51 3.67 53.01 312,316.07 (.65) (.59) (.79) (4.49) (67,849.21) 33 3.28 2.77 3.17 50.20 250,359.55 (.79) (.99) (.84) (6.19) (55,160.06) Table 4: Conditional Logits for selection decision 3 4 5 Choice set: 11 options Control Variables Income Average work hours Predictors Exposure Prior Fit Network Actors Subspecialty fixed effects n Log likelihood *p<0.05 0.139* 0.094* 0.110* 0.024 0.796* Not Incl 530 81.31 Not Incl. 493 69.71 0.178 0.034 Restricted Choice set: 9 options 0.062+ 0.085 7.469* Not Incl. 504 18.56 +p<0.01 34 6 4.016* Not Incl 479 23.98 0.215* -0.057 0.037 7.377* 3.693* Not Incl 472 -10.76 0.312* -0.089 0.054 9.793* 4.190* Included 429 -10.44 Table 5: Rank Ordered Logit s for rank 1 decision 2 3 4 5 Choice set: 11 options Control Variables Income Average work hours Predictors Prior Exposure Fit Network Actors Subspecialty fixed effects n Log likelihood *p<0.05 0.210* 0.016* Not Incl. 522 -771.61 Restricted Choice set: 9 options 0.170* 0.004 0.178 0.034 0.016 0.011 0.142* 0.699* 0.432* Not Incl. 491 -710.11 Not Incl. 500 -694.08 +p<0.01 35 6 Not Incl. 476 -665.55 0.009 -0.009 -0.011 0.575* 0.175* Not Incl. 465 -631.82 0.008 -0.016 -0.011 0.637* 0.191* Included 422 -533.91 REFERENCES: Ambrozy, D.M., Irby, D.M., Bowen, J.L., Burack, J.H., Carline, J.D., & Stritter, F.T. 1997. Role models’ perceptions of themselves and their influence on students’ specialty choices. Academic Medicine, 72: 1119-1121. Barshes, N.R., Vavra, A.K., Miller, A., Brunicardi, F.C., Goss, J.A., & Sweeney, J.F. 2004. General surgery as a career: A contemporary review of factors central to medical student specialty choice. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 199(5): 792-799. Beggs, S., Cardell, S. & Hausman, J. 1981. Assessing the potential demand for electric cars. Journal of Econometrics, 16: 1-19. Bland, C.J., Meurer, L.N., Maldonado, G. 1995. Determinants of primary care specialty choice: a non statistical meta-analysis of the literature. Academic Medicine, 70: 620-641. Bowen, D.E., Ledford, G.E., & Nathan, B.R. 1991. Hiring for the organization, not the job. Academy of Management Executive, 4: 35-51. Burack, J.H., Irby, D.M., Carline, J.D., Amrozy, D.M., Ellsbury, K.E., & Stritter, F.T. 1997. A study of medical students’ specialty choice pathways: trying on possible selves. Academic Medicine, 72: 534-541. Cable, D.M. & Judge, T.A. 1997. Interviewers’ perceptions of person-organization fit and organizational selection decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82: 546-561. Cable, D.M. & DeRue, D.S. 2002. The convergent and discriminate validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 875-884. Chapman, D.S., Uggerslev, K.L., Carroll, S.A., Piasentin, K.A., & Jones, D.A. 2005. Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlations of recruiting outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90: 928944. Chapman, R. G. & Staelin, R. 1982. Exploiting rank ordered choice set data within stochastic utility model. Journal of Marketing Research, 19: 288-301 Chatman, J.A. 1991. Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36: 459-484. Cheng, S., & Long J. S. 2005. Testing for IIA in the multinomial logit model. University of Connecticut, working paper. 36 Dorsey, R. E., Jarjoura, D., & Rutecki, G. W. 2003. Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 290(9): 1173-1178. Festinger, L. 1954. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7: 117140 Fouad, N. A. 2007. Work and vocational psychology: theory, research, and applications. Annual Review of Psychology, 58: 543-564. Goodman, P.S. 1977. Social comparison processes in organizations. In B.M. Staw & G.R. Salancik (Eds.), New directions in organizational behavior: 97-132. Chicago: St. Clair Press. Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structures: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3): 481-510. Guzzo, R. A., & Shea, G.P. 1992. Group performance and inter group relations in organizations. In M.D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.) Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology: 269-313. Hackman, J.R. & Oldham, G. 1980. Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Haussman, J. A. & Ruud, P. A. 1987. Specifying and testing econometric models for rankordered data. Journal of Econometrics, 34: 83-104. Holland, J.L. 1985. Making vocational choices. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Ibarra, H., & Andrews, S.B. 1993. Power, social influence, and sense making : Effects of network centrality and proximity on employee perceptions. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38: 277-303. Jansen, K., & Kristof-Brown, A.L. 2006. Toward a multi-dimensional theory of personenvironment fit. Journal of Managerial Issues, 28, 193-212. Kaufman, S., Mennin, S., Waterman, R., Duban, S., Hansbarger, C. Silverblatt, H., Obenshain, S.S., Kantrowitz, M., Becker, T., Samet, J., Wiese, W. 1989. The New Mexico experiment: educational innovation and institutional change. Academic Medicine, 64: 285-294. Kassenbaum, D.G. & Szenas, P.L.1995. Medical students’ career indecision and specialty rejection: roads not taken. Academic Medicine, 70: 937-943. Kilduff, M. 1990. The interpersonal structure of decision making: A social comparison approach to organizational choice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 47: 270-288. 37 Kristof, A.L. 1996. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurements, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49: 1-49. Kristof-Brown, A.L., Jansen, K.J., & Colbert, A.E. 2002. A policy capturing study of the simultaneous effects of fit with jobs, groups and organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 985-993. Kristof-Brown, A.L., Zimmerman, R. D., Johnson, E. C. 2005. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58: 281-342. Kulick, C.T., Oldham, G.R., & Hackman, J.R. 1987. Work design as an approach to person-environment fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31: 278-296. Leigh, P. J., Kravitz, R. L., Schembri, M. Samuels, S. J., and Mobley, S. 2002. Physician career satisfaction across specialties. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162: 15771584. Levine, J.M., & Moreland, R.L. 1990. Progress in small group research. In M.R. Rosenzweig & L. W. Porter (Eds.), Annual review of psychology, vol. 41: 585634. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews. McFadden, D. 1974. Conditional logit analysis of quantitative choice behavior. In Frontiers in Econometrics, Zarembka P. (ed). Academic Press: New York. Newton, D.A. & Grayson, M.S. 2003. Trends in career choice by US medical school graduates. The Journal of the America Medical Association, 290(9):1179-1182. O’Reilly, C.A., Chatman, J. & Caldwell, D.F. 1991. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3): 487-516. Osborn, E.H. 1993. Factors influencing students’ choice of primary care or other specialties. Academic Medicine, 68: 572-574. Pervin, L.A. 1968. Performance and satisfaction as a function of individual-environment fit. Psychological Bulletin, 69: 56-58. Resick, C.J., Baltes, B.B., & Walker-Shantz, C. 2007. Person-organization fit and work related attitudes and decisions: Examining interactive effects with job fit and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5): 1446-1455. 38 Rice, R.E. & Aydin, C. 1991. Attitudes toward new organizational technology: Network proximity as a mechanism for social information processing. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36: 219-244. Rubeck, R.F., Donnelly, M.B., Jarecky, R.M., Murphy-Spence, A.E., Harrell, P.L., & Schwartz, R.W. 1995. Demographic, educational, and psychosocial factors influencing the choice of primary care and academic medical careers. Academic Medicine, 70:318-320. Salancik, G.R., & Pfeffer, J. 1978. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23: 224-253. Sambunjak, D., Straus, S.E., & Marusic, A. 2006. Mentoring in academic medicine. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 296(9): 1103-1115. Shah, P.P. 1998. Who are employees’ social referents? Using a network perspective to determine referent others. Academy of Management Journal, 41(3): 249-268. Shah, P.P. 2000. Network destruction: The structural implications of downsizing. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3): 101-112. Shaver, M.J., & Flyer, F. 2000. Agglomeration economies, firm heterogeneity, and foreign direct investment in the United States. Strategic Management Journal, 21: 1175-1195. Sigelman, L. 1983. Reporting the news: An organizational analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 79: 132-151. Smith, L.G., Feit, E., & Mueller, D. 1997. Internal medicine residents’ assessment of the subspecialty fellowship application process. Academic Medicine, 72(2): 152-154. West, C. P., Popkave, M. A., Schultz, H.J., Weinberger, S.E., & Kolars, J.C. 2006. Changes in career decisions of internal medicine residents during training. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145(10): 774-449. Wright, S., Wong, A., & Newill, C. 1997. The impact of role models on medical students. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12: 53-56. 39