File

advertisement

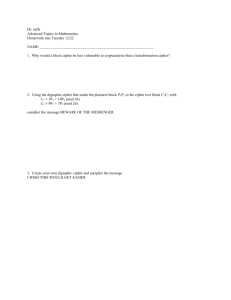

1 “ADVANCED ENCRYPTION STANDARDS (AES)” (Implementation of RIJNDAEL Algorithm) (UNDER THE THEME : NETWORK SECURITY) P.CHANAKYA. Y9MC95008, IV Semester, II MCA, St.Ann’s College of P.G. Studies, Chirala – 523 187, Contact: funnychanu@gmail.com www.funnychanu.weebly.com/seminor Abstract In the first few decades of their existence, computer networks were rarely used by common man. But now-a-days due its use by millions of ordinary citizen's, network security is looming on the horizon as a potentially massive problem. Security deals mainly with secrecy, authentication, non-repudiation and integrity control. Secrecy has to do with keeping information out of hands of unauthorized users. Authentication deals with determining whom 2 you are talking before revealing sensitive information. Non repudiation deals with digital signatures to make sure that the message received by a person was really the one sent and not something that a malicious adversary modified in transit or concocted. Data integrity is a service which addresses the unauthorized alteration of data. Cryptography is about the prevention and detection of cheating and other malicious activities. Providing secrecy allows people to carry over the confidence found in the physical world to the electronic world, thus allowing people to do business electronically without worries of deceit and deception. In this paper, the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) algorithm Rijndael has been implemented & this is approved as the AES algorithm by NIST (National Institute of Standards & Technology). The algorithm encrypts and decrypts only text files with extensions such as *.txt, *.doc and *.c etc. The expected strength, advantages and limitations of this project have been discussed. 1. INTRODUCTION TO CRYPTOGRAPHY Cryptography today might be summed up as the study of techniques and applications that depend on the existence of difficult problems. Cryptanalysis is the study of how to compromise (defeat) cryptographic mechanisms, and Cryptology (from the Greek kryptos logos, meaning "hidden word") is the discipline of cryptography and cryptanalysis combined. To most people, cryptography is concerned with keeping communications private. 3 Encryption is the transformation of data into a form that is as close to impossible as possible to read without the appropriate knowledge (a key). Its purpose is to ensure privacy by keeping information hidden from anyone for whom it is not intended, even those who have access to the encrypted data. Decryption is the reverse of encryption; it is the transformation of encrypted data back into an intelligible form. Encryption and decryption generally require the use of some secret information, referred to as a key. For some encryption mechanisms, the same key is used for both encryption and decryption; for other mechanisms, the keys used for encryption and decryption is different. The general model of Encryption and Decryption is shown in the figure below. Intruder Plain Text, P Plain Text, P Decryption Method Encryption Method Encryption Key, K Cipher Text, C=E k (P) Decryption Key The Encryption Model Today's cryptography is more than encryption and decryption. While modern cryptography is growing increasingly diverse, cryptography is fundamentally based on problems that are difficult to solve. A problem may be difficult because its solution requires some secret knowledge, such as decrypting an encrypted message or signing some digital document. The problem may also be hard because it is intrinsically difficult to complete, such as finding a message that produces a given hash value. 4 There are two types of cryptosystems: secret-key and public-key cryptography. In secret-key cryptography, also referred to as symmetric cryptography, the same key is used for both encryption and decryption. 1.1 Cryptanalysis The process of attempting to discover the plain text or key is known as Cryptanalysis. The strategy used by the cryptanalyst depend s upon the nature of the encryption scheme and the information available to the cryptanalyst. The following table summarizes the various types of cryptanalytic attacks on encrypted messages. Type of Attack Cipher text only Known Plain text Information known to Cryptanalyst Encryption algorithm Cipher text to be decoded Encryption algorithm Cipher text to be decoded One or more plain text - cipher text pairs formed with the secret key Chosen Plain text Encryption algorithm Cipher text to be decoded Plain text message chosen by the cryptanalyst, with its corresponding cipher text generated with the secret key An encryption scheme is computationally secure if the cipher text generated by the scheme meets one or both of the following criteria: The cost of breaking the cipher exceeds the value of the encrypted information. The time required to break the cipher exceeds the useful lifetime of the information. 5 1.2 Applications of Cryptography Cryptography is extremely useful; there is a multitude of applications, many of which are currently in use. Some of the more simple applications are secure communication, identification, authentication, and secret sharing. More complicated applications include systems for electronic commerce, certification, secure electronic mail, key recovery, and secure computer access. Cryptography is not confined to the world of computers. Cryptography is also used in cellular (mobile) phones as a means of authentication; that is, it can be used to verify that a particular phone has the right to bill to a particular phone number. This prevents people from stealing ("cloning'') cellular phone numbers and access codes. Another application is to protect phone calls from eavesdropping using voice encryption. 2. HISTORY In 1972 and 1974, the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST) issued the first public request for an encryption standard. 6 The result was DES, arguably the most widely used and successful encryption algorithm in the world. Despite its popularity, DES has been plagued with controversy. But recent advances in distributed key search techniques have left no doubt in anyone's mind that its key is simply too short for today's security applications. More fundamentally, the 64-bit block length shared by DES and most other well-known ciphers opens it up to attacks when large amounts of data are encrypted under the same key. In response to a growing desire to replace DES, NIST announced the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) program in 1997. NIST's call requested a block cipher. Block ciphers can be used to design stream ciphers with a variety of synchronization and error extension properties, one way hash functions, message authentication codes, and pseudorandom number generators. NIST specified several other design criteria: Longer Key Length Larger Block Size Faster Speed and Greater Flexibility While no single algorithm can be optimized for all needs, NIST intends AES to become the standard symmetric algorithm of the next decade. RC6, Rijndael, SAFER, Serpent and Twofish were the finalists. Among these the NIST has accepted Rijndael as AES and is also approved by the U.S Government recently. It meets the entire required NIST criteria, efficient on various platforms; etc.and some strenuous design requirements, performance as well as cryptographic, of our own. Rijndael is developed by Joan Daemen and Vincent Rijmen. Pronunciation of Rijndael: “Rain Doll” or “Rhine Dahl”. 3. INTRODUCTION TO RIJNDEAL ALGORITHM This standard specifies the Rijndael algorithm, a symmetric block cipher that can process data blocks of 128 bits, using cipher keys with lengths of 128, 192, and 256 bits. 7 Rijndael was designed to handle additional block sizes and key lengths. Throughout the remainder of this standard, the algorithm specified herein will be referred to as “the AES algorithm.” The algorithm may be used with the three different key lengths indicated above, and therefore these different “flavors” may be referred to as “AES-128”, “AES-192”, and “AES-256”. Algorithm Parameters, Symbols, and Functions The following algorithm parameters, symbols, and functions are used throughout this standard: AddRoundKey ( ) Transformation in the Cipher and Inverse Cipher in which a Round Key is added to the State using an XOR operation. The length of a Round Key equals the size of the State (i.e., for Nb = 4, the Round Key length equals 128 bits/16 bytes). InvMixColumns ( ) Transformation in Inverse Cipher that is the inverse of MixColumns ( ). InvShiftRows ( ) Transformation in the Inverse Cipher that is the inverse of ShiftRows ( ). InvSubBytes ( ) Transformation in the Inverse Cipher that is the inverse of SubBytes ( ). K Cipher Key. MixColumns ( ) Transformation in the Cipher that takes all of the columns of the State and mixes their data (independently of one another) to produce new columns. Nb Number of columns (32-bit words) comprising the State. For this standard, Nb = 4. Nk Number of 32-bit words comprising the Cipher Key. For this standard, Nk = 4, 6, or 8. Nr Number of rounds, which is a function of Nk and Nb (which is fixed). For this standard, Nr = 10, 12, or 14. Rcon [ ] The round constant word array. RotWord ( ) Function used in the Key Expansion routine that takes a four-byte word and performs a cyclic permutation. 8 ShiftRows ( ) Transformation in the Cipher that processes the State by cyclically shifting the last three rows of the State by different offsets. SubBytes ( ) Transformation in the Cipher that processes the State using a nonlinear byte substitution table (S-box) that operates on each of the State bytes independently. SubWord ( ) Function used in the Key Expansion routine that takes a four-byte input word and applies an S-box to each of the four bytes to produce an output word. XOR Exclusive-OR operation. Exclusive-OR operation. Multiplication of two polynomials (each with degree < 4) modulo x4 + 1. • Finite field multiplication. 4. IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES 9 4.1 Key Length Requirements An implementation of the AES algorithm shall support at least one of the three key lengths: 128, 192, or 256 bits (i.e., Nk = 4, 6, or 8, respectively). Implementations may optionally support two or three key lengths, which may promote the interoperability of algorithm implementations. 4.2 Keying Restrictions No weak or semi-weak keys have been identified for the AES algorithm, and there is no restriction on key selection. 4.3 Parameterization of Key Length, Block Size, and Round Number This standard explicitly defines the allowed values for the key length (Nk), block size (Nb), and number of rounds (Nr). However, future reaffirmations of this standard could include changes or additions to the allowed values for those parameters. Therefore, implementers may choose to design their AES implementations with future flexibility in mind. 4.4 Implementation Suggestions Regarding Various Platforms Implementation variations are possible that may, in many cases, offer performance or other advantages. Given the same input key and data (plaintext or cipher text), any implementation that produces the same output (cipher text or plaintext) as the algorithm specified in this standard is an acceptable implementation of the AES. 5. ADVANTAGES & LIMITATIONS 10 5.1 Advantages Implementation aspects: Rijndael can be implemented to run at speeds unusually fast for a block cipher on a Pentium (Pro). There is a trade-off between table size/performance. Rijndael can be implemented on a Smart Card in a small amount of code, using a small amount of RAM and taking a small number of cycles. There is some ROM/performance trade off. The round transformation is parallel by design, an important advantage in future processors and dedicated hardware. As the cipher does not make use of arithmetic operations, it has no bias towards big or little endian processor architectures. Simplicity of Design: The cipher is fully “self-supporting”. It does not make use of another cryptographic component, S-boxes “lent” from well-reputed ciphers, bits obtained from Rand tables, digits of p or any other such jokes. The cipher does not base its security or part of it on obscure and not well understood interactions between arithmetic operations. The tight cipher design does not leave enough room to hide a trapdoor. Variable block length: The block lengths of 192 and 256 bits allow the construction of a collision-resistant iterated hash function using Rijndael as the compression function. The block length of 128 bits is not considered sufficient for this purpose nowadays. Extensions: The design allows the specification of variants with the block length and key length both ranging from 128 to 256 bits in steps of 32 bits Although the number of rounds of Rijndael is fixed in the specification, it can be modified as a parameter in case of security problems. 5.2 Limitations 11 The limitations of the cipher have to do with its inverse: The inverse cipher is less suited to be implemented on a smart card than the cipher itself: it takes more code and cycles. (Still, compared with other ciphers, even the inverse is very fast) In software, the cipher and its inverse make use of different code and/or tables. In hardware, the inverse cipher can only partially re-use the circuitry that implements the cipher. 6. EXPECTED STRENGTH Rijndael is expected, for all key and block lengths defined, to behave as good as can be expected from a block cipher with the given block and key lengths. The most efficient keyrecovery attack for Rijndael is exhaustive key search. Obtaining information from given plain text-cipher text pairs about other plaintext-cipher text pairs cannot be done more efficiently than by determining the key by exhaustive key search. The expected effort of exhaustive key search depends on the length of the Cipher Key and is: for a 16-byte key, 2127 applications of Rijndael for a 24-byte key, 2191 applications of Rijndael for a 32-byte key, 2255 applications of Rijndael Despite the large amount of symmetry, care has been taken to eliminate symmetry in the behavior of the cipher. This is obtained by the round constants that are different for each round. The fact that the cipher and its inverse use different components practically eliminates the possibility for weak and semi-weak keys, as existing for DES. 7. CONCLUSION 12 Cryptography has a long and colorful history. It is extremely useful; there is a multitude of applications, many of which are currently in use. Some of the more simple applications are secure communication, identification, authentication, and secret sharing. More complicated applications include systems for electronic commerce, certification, secure electronic mail, key recovery, and secure computer access. No block cipher is ideally suited for all applications, even one offering a high level of security. This is a result of inevitable tradeoffs required in practical applications. They are listed below: speed requirements and memory limitations (e.g., code size, data size, cache memory) constraints imposed by implementation platforms (e.g. , hardware, software, chip cards) properties of various modes of operation efficiency must typically be traded off against security 13 Reading List and Bibliography Applied Cryptography - Bruce Schneier (John Wiley & sons) Handbook of Applied Cryptography - Alfred J. Menezes Pall C. van Oorschot Scott A. Vanstone Network Security Essentials - William Stallings Let us C - Yashavant P. Kanetkar http://csrc.nist.gov/encryption/aes/ http://fp.gladman.plus.com http://www.rijndael.com http://www.esat.kuleuven.ac.be/~rijmen/rijndael