Forthcoming in World Politics April 2014 Domestic Institutions

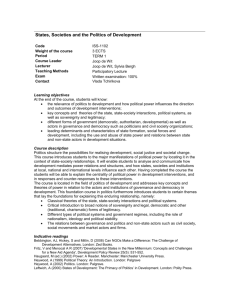

advertisement