J Lattas proposal for chapter in IE book

advertisement

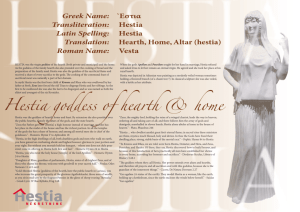

Page 1 of 16 Title: Teaching and Imagination: Towards a Phenomenological Account of the University Teacher for the 21st Century Author: Dr Judy Lattas Institution: Macquarie University Position: Director of the Interdisciplinary Women’s Studies, Gender and Sexuality program in the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Arts; Associate Dean of Learning and Teaching in the Division of Society, Culture, Media and Philosophy (2006-8) Email: jlattas@scmp.mq.edu.au Bio: Dr Judy Lattas has been teaching in women’s studies and gender at Macquarie since 1989. In 1998 she was awarded her PhD for a thesis entitled “Politics in Labour”, a deconstructivist reading of Hannah Arendt on the philosophical conditions of totalitarianism. In her research she is interested most recently in the popular right in Australia, publishing on Pauline Hanson, on gun activism, on secessionist micronations and on the Cronulla riots. In the field of Learning and Teaching her scholarship includes “Inquiry Based Learning: a Tertiary Perspective” in Agora (the quarterly journal of the History Teachers’ Association of Victoria), February 2009 and “Dear Learner: Shame and the Dialectics of Enquiry” (winner of the International Journal of the Humanities International Award for Excellence in the area of new directions in the humanities) International Journal of the Humanities March 2009 Proposal accepted as: chapter for book on Imaginative Education What is teaching, as distinct from learning? In the proliferation of the phrase ‘teaching and learning,’ and the increasing normalisation of its correction into ‘learning and teaching’ – or simply ‘learning’ - this is a question for our time. Teaching is everywhere lauded in the new university. Yet its repudiation is being led by those in the highest places in higher education policy and the scholarship of teaching. It is not to its old rival, research, that teaching is losing out; rather it is to a new preoccupation with the student, and a new rhetoric in which there are no more teachers, only learners. In this chapter I respond to the disappearance of teaching in the discourse of learning with a contemplation of its specific character, and a contribution towards a phenomenological account of the university teacher. Imaginative Education (IE) practitioners who are interested in engaging their imaginations in teaching, in primary and secondary as well as tertiary education, need to be able to grasp what might be called the essence of teaching. This is in a world that is overfull of truths (in terms of statements of teaching excellence, shifting historical models and popular iconography) and yet is losing the symbolic mechanism through which the truth of teaching may be revealed. An object may only have truth, or an essence, when it is defined against another that belongs to its conceptual universe - and in the case of the binary opposition, that complements and completes it. For the teacher, the other object is the student. Teacher and student emerge together in a relation of reciprocal identity, mutual exclusion and mutual exhaustion. Each is for the other, a mirror of the other; but is not the other. Occasions when ‘the teacher is a student’ or ‘the student is a teacher’ feature as exceptions that prove the rule. They become striking in the same way that ‘the girl is a boy’ is able to register its impact. The reference is to a norm of clearly distinguished meanings, and it is this norm that is retreating with the advance of a totalising construction of learning. The idea that ‘we are all learners’ is part of the heralding of ‘lifelong learning’ that has come with the embrace of new technologies of knowledge production and distribution, and their decentring of the educational institution. Willing to meet the challenge head on, administrators in these institutions sought to secure their markets by mapping their place in the unending journey and unlimited resource pool of the internet, and by tapping into the emerging rhetoric. Schools and universities now prepare the student for a lifetime of learning Page 2 of 16 (rather than for a job, or for entry into an elite circle of knowledge keepers). The apparent democratisation of access to education, and democratisation of the order of knowledge, attracted those interested in overturning the hierarchies of power in the teacher-student and academy-world relation. They grafted their studies of the psychology of learning and cocreation of knowledge (constructionism) onto the discourse of ‘student-centred’ and ‘studentled’ teaching and learning. The result has been a two-way surge of interest in the constructionist pedagogies of Problem Based Learning (PBL), Enquiry Based Learning (EBL)1, Discovery Based Learning, ‘andragogical’ (adult) learning and so on. In Australia, several universities are introducing measures to expand the take up of these pedagogies across the board, in the arts and humanities as well as the sciences and vocational training programs.2 It is in these pedagogies that the conventional role of the teacher is most deeply questioned, and, in much of the literature, recast if not relinquished in the role of ‘facilitator.’ In the extreme constructionist position, a renunciation of teaching can be found in the articulation of a goal of ‘learning without teaching;’ a flattening out of the teacher-student order to the extent that not only are there no podium style lectures, but no instruction takes place; no texts or preferred readings are set; and no disciplinary foundation is established. The teacher is neither represented nor required in the pure PBL/EBL classroom. It is the constructionist epistemology, however, which holds the most interest and potential for IE practice. A focus on the dynamics of the learning process and the role of the creative function in the making of knowledge is highly appropriate as a starting point for explorations in this field of endeavour. My concern is not to dispute this starting point. It is rather to argue for a clear recognition of the profession of teacher, and the crucial part that teachers play in the scene of learning that is called upon in constructionist literature, in all the paths that might open up along the way. Here the issue of suggested models of the teacher is critical. In PBL/EBL writing, the ideal model of teaching (such as it remains in the idea of facilitating) is the maieutic one, or the Socratic model of the teacher as midwife. This is set against a model of the teacher as master, cast as the traditional model. The master is a holder of knowledge, a revered high scholar who inducts selected learner-apprentices into the hallowed ranks of the enlightened few. The erudition of the master is delivered to the learner-apprentice in a direct transmission from one who is full of knowledge, to one who lacks knowledge. The mode of delivery is the lecture, sent via podium speech, and received in silence by passive listeners. To this account is counter-posed the preferred account of the facilitator-midwife. This quasi-Socratic figure assists in the delivery of knowledge that comes from within the learner-labourer. Both learner and teacher here are maternal figures in that one is heavy with the child of her thought processes, and the other is primarily nurturing and supporting. Rather than being full of knowledge, the facilitator-midwife is equipped with the kind of skill and wisdom that comes from experience and not scholarship. Authority, along with expert knowledge, is repudiated in the teacher on this model. I find this preferred model of the teacher, as it is being advanced in constructionist literature, to be just as problematic as the traditional model that these writers hold up for rejection. In her 1994 essay ‘The Teacher’s Breasts’3 and her 1997 book, Feminist Accused of Sexual Harassment,4 Jane Gallop offers a thoroughgoing critique of the maternalist norm of the university teacher. Gallop is a well-known feminist theorist who was herself formally charged with sexual harassment – not because of any sexual bullying or innuendo, she maintains, but simply because she exhibited the kind of power and authority over her students, including her female students, that any senior professor would, male or female.5 This violated an unspoken honour code amongst feminists, she says. In the situation of the university, she finds that when feminist teachers assume any kind of authority, instead of Page 3 of 16 being like sisters or mothers, they are accused of being authoritarian and of betraying the cause. They are seen as being ‘as bad as the men’ - and so worse than the men, for calling themselves feminist. This can go so far as to be called a form of sexual harassment of women students. This is actually what she found herself accused of, in the university she worked in. She maintains in her writing that it was simply because she was seen as being too authoritative by everybody, especially her young female students. Her plea is for the teacher’s authority to be recognised and defended as legitimate and essential. The philosopher who provides the most powerful recognition and defence of the teacher’s authority is the maverick phenomenologist Hannah Arendt.6 Mordechai Gordon writes about this in his edited collection of interpretations of Arendt on education.7 Gordon argues that Arendt’s understanding of the proper authority of teachers is very different from that given in the portrayal of the authoritarian master. In Arendt’s vision, it is the students’ potential for imaginative creation and what she calls renewal (in the key concept of natalism that can be found in all her works) that is provoked in the exercise of authority in teachers; the authority that provides a trust-enabling and positive communication that, to the best of their knowledge, ‘this is our world.’ The enactment of this authority primarily implies the teacher’s responsibility - responsibility for the world that is, and for the world that may be given birth to in the process of learning. It is not only on the question of authority that the new pedagogical account of the maieutic teacher is inadequate, in my view (and in the view of Jacques Derrida, who commented on the sterility of midwife figure of the teacher in his 2004 book Dissemination).8 I find that it is just as problematic to determine that the facilitator-midwife can only deliver the knowledge that comes from outside the classroom, in the form of the student’s own prior understandings, as it is to determine that the master-expert can only deliver the knowledge that that comes from outside the classroom, in the form of his own prior scholarship. My suggestion is that knowledge might be considered as an event that comes in a situation, such as within a classroom, when people respond to one another and to an idea, in the moment (or the re-created moment) of its composition. The role of the teacher here is fundamental. I describe this role in a phenomenological consideration of traces of the meaning of the teacher in philosophical accounts, literature, popular culture and etymology. The closest match to the traditional model of the teacher, as cited in constructionist literature, is the Humboldtian figure that Baert and Shipman (2005) reflect upon in their critical analysis of the effects of ‘audit culture’ on the contemporary university.9 In their identification with a discipline, the academic teachers proposed by German humanist von Humboldt would be highly committed, self regulating scholars who could manage their own profession, and be trusted with their culture’s intellectual legacy. In the current context, I find that considerable care needs to be taken in surrendering what is a long accepted, and strategically important, figure of the professional teacher. Other accounts of the teacher that I consult include the Byzantine Erotapokriseis tradition,10 the Biblical teacher as ‘host’,11 a phenomenological construction inspired by Merleau Ponty,12 and writing by Levinas on the teaching of philosophy.13 Romantic notions of the teacher and imagination are considered in readings of Blake’s ‘The Schoolboy’ and other texts. In popular culture, images of the good teacher who liberates the soul squashed by social inequality, and of the bad teacher who squashes the soul as an agent of social conditioning, are consulted. Etymological considerations yield further representations of the teacher, particularly with regard to the root meaning of ‘to teach’ as ‘to point to’ or to indicate. It is the Arendtian notions of natality and belatedness, however, that I find most engaging and most promising, read alongside her account of the Life of the Mind.14 From this contemplation I offer my own sense of what Imaginative Education might look like when the Page 4 of 16 pivotal work of the teacher is brought into focus. A brief sketch of one classroom activity, in a medium size, introductory, interdisciplinary university subject, is given to illustrate my account in its practical dimension. Page 5 of 16 Cahen, Didier, ‘Derrida and the question of education’. Derrida & education, edited by Gert J. J. Biesta and Denise Egéa-Kuehne. London; New York: Routledge, 2001 LB880.D48 D47 2001 ‘Derrida tried to think of teaching as the irreducible other – infinitely other – of pedagogy.’ p. 17 Derrida quote: ‘Rhetoric may amount to the violence of theory, which reduces the other when it leads the other, whether through psychology, demagogy, or even pedagogy which is not instruction. The latter descends from the heights of the master, whose absolute exteriority does not impair the disciple’s freedom.’ ‘Violence and Metaphysics’ in Writing and Difference 1978 p. 106 p. 17 Blanchot quote: ‘...one must not be satisfied with attributing to the master the part of role model, and with defining his/her link with the pupil as an existential link. The master represents an absolutely other region of space and time...The master gives nothing to know which does not remain determined by the indeterminable “unknown” he/she represents, unknown which does not affirm itself by the mystery, the prestige, and the erudition of he/she who teaches, but by the infinite distance between A and B...to go to the familiarity of things while reserving their strangeness, to relate to everything by the vry experience of the interruption of relations, this is nothing other than to hear something speak, and to learn how to speak. The relation of master to disciple is the very relation of the spoken word...’ Blanchot l’entretien infini 1969:4 Francis Fischer two schemes of teaching p. 19 corresponds to master & maieutic; teaching via Derrida as unveiling Audit culture, technology p. 20 Derrida quote: ‘On the one hand, pupils and students as well as teachers must be given the possibility, in other words the conditions of philosophy. A master must initiate, introduce, form, and so on, his disciple to this. The master who himself must have been previously formed, introduced, initiated remains someone other for his disciple. Keeper, guarantor, mediator, predecessor, elder, he must represent the word, the thought or the knowledge of the other: heterodidactic. But on the other hand, whatever the cost, one will not renounce the autonomist ad autodidactic tradition of philosophy. The master is nothing but a mediator who must efface himself. How can the necessity of the presence [avoir-lieu] of a master and the necessity of his effacement [non-lieu] be reconciled? What unbelievable topology do we require to reconcile the heterodidactic and the autodidactic?’ 1990 520-1 ‘Les antinomies...’The Right of Philosophy French ed Derrida, deconstruction, and education: ethics of pedagogy and research, edited by Peter Pericles Trifonas and Michael A. Peters. Oxford: Blackwell pub., c2004. LB880.D48 D49 1 Introduction : Derrida and the philosophy of education / Peter Trifonas 2 Applied Derrida : (mis)reading the work of mourning in educational research / Patti Lather 3 The teaching of philosophy : renewed rights and responsibilities / Denise Egea-Kuehne 4 The ethics of science and/as research : deconstruction and the orientations of a new academic responsibility / Peter Trifonas 5 Archiving Derrida / Marla Morris 6 Derrida, pedagogy and the calculation of the subject / Michael A. Peters 7 Signal event context : trace technologies of the habit@online / Robert Luke Page 6 of 16 8 Dewey, Derrida, and ’the double bind’ / Jim Garrison. Get from work: Leon Donski on conspiracy, Nancy Jay on dualism Derrida, deconstruction, and education: ethics of pedagogy and research, edited by Peter Pericles Trifonas and Michael A. Peters. Oxford: Blackwell pub., c2004. LB880.D48 D49 Page 7 of 16 What is teaching, as distinct from learning? Responsibility (for love of the world). As in Arendt. The world always withdrawing/appearing. The job of the teacher is to re-present it, keep the flame going, reignite. As always in process of rebirth, link to natalism, but it is not ‘delivery’ – has to be sparked in engagement with the learners. Find a myth to narrate the model that this might correspond to, neither master nor midwife – match lighter??? Atlas to carry the world? No, go with Hestia. Responsibility for keeping the flame alight (has to keep relighting it). Hestia has come to represent hearth & home but this is not quite right. She represent more public hearth than private. – or both. She insists on her virginity – so does not dwell in mortal world, does not represent the private as opposed to public (which is the world, for Arendt). She presides over both, guards the possibility of both. Both Metis & Athena represent wisdom but my model of teaching is neither of those. Hestia is neither the mother (Metis – effaced within Zeus) – maternal figure of teaching – nor the enabled child (Athena – fully present and armed for the world; Plato makes poros, or "creative ingenuity", the child of Mètis). The teacher has a special being that is neither of these, but her special role is to keep the possibility of both alight. She carries the world in a more important way than Atlas. Page 8 of 16 The Myth of Atlas Atlas was a Titan, one of the firstborn sons of Earth. Atlas made the mistake of siding with his brother Cronus in a war against Zeus. In punishment, he was compelled to support the weight of the heavens by means of a pillar on his shoulders. He was temporarily relieved of this burden by Heracles, who needed the Titan's aid in procuring the Golden Apples of the Hesperides. In connection with another heroic quest, Atlas divulged the whereabouts of the Graeae to Perseus. The encounter of Atlas and Heracles came about when Eurystheus, the great hero's cousin and taskmaster, challenged him to retrieve the Golden Apples of the Hesperides. The Hesperides, or Daughters of Evening, were nymphs assigned by the goddess Hera to guard certain apples which she had received as a wedding present. These were kept in a grove surrounded by a high wall and guarded by a dragon named Ladon, whose many heads spoke simultaneously in a babel of tongues. The grove was located in some far western land in the mountains named for Atlas. Heracles had been told that he would never get the apples without the aid of Atlas. The Titan was only too happy to oblige, since it meant being relieved of his burden. He told the hero to hold the pillar while he went into the garden of the Hesperides to retrieve the fruit. But first, Heracles would have to do something about the noisily vigilant dragon, Ladon. This was swiftly accomplished by means of an arrow over the garden wall. Then Heracles took the pillar while Atlas went to get the apples. He was successful and returned quickly enough, but in the meantime he had realized how pleasant it was not to have to strain for eternity keeping heaven and earth apart. So he told Heracles that he'd have to fill in for him for an indeterminate length of time. And the hero feigned agreement to this proposal. But he said that he needed a cushion for his shoulder, and he wondered if Atlas would mind taking back the pillar just long enough for him to fetch one. The Titan graciously obliged, and Heracles strolled off, omitting to return Hestia was the oldest daughter of Cronus and Rhea and one of the twelve Olympian gods. The word 'hestia' in Greek means the heart, the place in the house where the fire was maintained. So, Hestia was the goddess of the heart. She was venerated in the households and in the temples. In ancient Greece, the cult of the heart was cherished in every house. That was the place where family gathered. The father of the family used to play the role of the goddess' priest. Also, in every town there was a communal heart sacred to Hestia. The common heart of all Greece was symbolized by Hestia of Delphi. There are almost no legends of Hestia. All that is known about her is that both Poseidon and Apollo tried to win her love. In order to stop them in their attentions, she vowed to Zeus she would remain a virgin forever. Zeus accepted her vow and granted her with special honours. According to some versions, Hestia later resigned her seat at the high table in favour of Dionysus, who then became one of the twelve great Olympian gods. Page 9 of 16 Although Hestia was venerated throughout Greece, she didn't have any temples. In the art, she was shown on several red figured vases, wearing a veil and holding a sceptre or flower, sometimes seated, sometimes standing, but always in a pose of immobility Page 10 of 16 Hestia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For other uses, see Hestia (disambiguation). Hestia The Giustiniani Hestia in O. Seyffert, Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1894 Goddess of the Hearth Abode Delphi Symbol Hearth Parents Cronus and Rhea Siblings Poseidon, Hades, Demeter, Hera, Page 11 of 16 Zeus, Chiron This box: view • talk In Greek mythology, virgin Hestia, (Roman Vesta) daughter of Cronus and Rhea, (ancient Greek Ἑστία') is the goddess of the hearth, of the right ordering of domesticity and the family, who received the first offering at every sacrifice in the household. In the public domain, the hearth of the prytaneum functioned as her official sanctuary. With the establishment of a new colony, flame from Hestia's public hearth in the mother city would be carried to the new settlement. In Roman mythology, her more specifically civic approximate equivalent was Vesta, who personified the public hearth, and whose cult round the ever-burning hearth bound Romans together in the form of an extended family. The similarity of names between Hestia and Vesta, is misleading: "The relationship hestia-histie-Vesta cannot be explained in terms of Indo-European linguistics; borrowings from a third language must also be involved," Walter Burkert has written[1]. At a deep level her name means "home and hearth", the oikos, the household and its inhabitants. "An early form of the temple is the hearth house; the early temples at Dreros and Prinias on Crete are of this type as indeed is the temple of Apollo at Delphi which always had its inner hestia" [2] Among classical Greeks the altar was always in the open air with no roof but the sky, and that of the oracle at Delphi was the shrine of the Goddess before it was assumed by Apollo. The Mycenaean great hall, such as the hall of Odysseus at Ithaca was a megaron, with a central hearthfire. The hearth fire of a Greek or a Roman household was not allowed to go out, unless it was ritually extinguished and ritually renewed, accompanied by impressive rituals of completion, purification and renewal. Compare the rituals and connotations of an eternal flame and of sanctuary lamps. At the more developed level of the polis, Hestia symbolizes the alliance between the colonies and their mother cities. Contents [hide] 1 As an Olympian 2 Leaving Olympus 3 Other worship 4 In mythology 5 References 6 Sources 7 External links [edit] As an Olympian Page 12 of 16 Hestia is one of the three Great Goddesses of the first Olympian generation: Hestia, Demeter and Hera. She was described as both the oldest and youngest[3] of the three daughters of Rhea and Cronus, the sisters to three brothers Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades. Originally listed as one of the Twelve Olympians, Hestia gave up her seat in favour of newcomer Dionysus to tend to the sacred fire on Mt. Olympus. Every family hearth was her altar. Of the Olympian gods, Hestia has the fewest exploits "since the hearth is immovable Hestia is unable to take part even in the procession of the gods, let alone the other antics of the Olympians," Burkert remarks.[4] Sometimes this is assumed to be due to her passive, nonconfrontational nature. This nature is illustrated by her giving up her seat in the Olympian twelve to prevent conflict. She is considered to be the first-born of Rhea and Kronus; this is evidenced by the fact that in Greek (and later Roman) culture ritual offerings to all gods began with a small offering to Hestia; the phrase "Hestia comes first" from ancient Greek culture denotes this. Immediately after their birth, Kronus swallowed Hestia and her siblings except for the last and youngest, Zeus, who later rescued them and led them in a war against Kronus and the other Titans. Hestia, the eldest daughter "became their youngest child, since she was the first to be devoured by their father and the last to be yielded up again" (Kereny 1951:91) — the clearest possible example of mythic inversion, a paradox that is noted in the Homeric hymn to Aphrodite (ca 700 BCE): She was the first-born child of wily Kronus — and youngest too. Poseidon, and Apollo of the younger generation each aspired to court Hestia, but the goddess was unmoved by Aphrodite's works and swore on the head of Zeus to retain her virginity. The Homeric hymns, like all early Greek literature, are concerned to reinforce the supremacy of Zeus, and Hestia's oath taken upon the head of Zeus is an example of surety. A measure of the goddess's ancient primacy—"queenly maid...among all mortal men she is chief of the goddesses", in the words of the Homeric hymn— is that she was owed the first as well as the last sacrifice at every ceremonial assembly of Hellenes, a pious duty related by the mythographers as the gift of Zeus, as if it had been his to bestow: another mythic inversion if, as is likely, the ritual was too deep-seated and essential for the Olympian reordering to overturn. There are theories (by modern neopagans among others) that Hestia, as goddess of "home and hearth", was one of the most ancient of all gods later worshipped as Olympians; as a maternal goddess of humans finding safety and homes in caves around a fire, worship of Hestia, by other names, may literally be hundreds of thousands of years old and has continued through Classical Greek times to the present day. [edit] Leaving Olympus Hestia, not wanting to be involved in the gods' quarrels, decided to leave Olympus to tend to her sacred hearth. She became a lesser goddess in the same ranks of Pan and Dionysus, the latter of whom later rose to the place of Olympian when Zeus chose him to take Hestia's place. [edit] Other worship Page 13 of 16 "Hestia full of Blessings", Egypt, 6th century tapestry (Dumbarton Oaks Collection). The "great hall" of Minoan-Mycenaean culture as well as the type of earliest enclosed site built for worship on the Greek mainland is the megaron: the name of the Goddess who was venerated in the Helladic megara is not recorded, but at the center of each holy site laid bare by archaeologists was normally a hearth. In his account of the Fasti of the Roman year, Ovid twice recounted an anecdote of Priapus's foiled attempt on a sleeping nymph: once he told it of the nymph Lotis[5] and then again, calling it a "very playful little tale", he retold it of Vesta, the Roman equivalent of Hestia.[6] In the anecdote, after a great feast, when the immortals were all either passed out drunk or asleep, Priapus — who had grotesquely large genitalia — spied Lotis/Vesta and was filled with lust for her. He quietly approached the nymph, but the braying of an ass awoke her just in time. She screamed at the sight and Priapus ran away. [edit] In mythology Hestia figures in few myths: she did not roam or have any adventures. The Homeric hymn To Hestia is consequently brief, simply an invocation of five lines, a prelude: Hestia, you who tend the holy house of the lord Apollo, the Far-shooter at goodly Pytho, with soft oil dripping ever from your locks, come now into this house, come, having one mind with Zeus the allwise: draw near, and withal bestow grace upon my song. In the hymn, Hestia is located in ancient Delphi (rather than at the hearth of Zeus on Mount Olympus), which was considered the central hearth of all the Hellenes. In classical Greek art, Hestia was depicted as a woman modestly cloaked in a head veil. Page 14 of 16 METIS was one of the Okeanides and the Titan goddess of good counsel, advise, planning, cunning, craftiness and wisdom. She functioned as the counsellor of Zeus during the Titan War, and devised the plan which forced Kronos to regurgitate his children. However, Zeus, in fear of a prophecy that she would bear a son more powerful than himself, swallowed the pregnant Metis whole. Their daughter, Athena, was later born fully grown from the god's head. Zeus is himself titled Mêtieta, "the wise counsellor," in the Homeric poems. It should be noted that most poets and mythographers represent Athena as a "motherless goddess," with no mention made of Metis. Plato makes poros, or "creative ingenuity", the child of Mètis.[5] Metis (mythology) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In Greek mythology, Metis (Μῆτις) was of the Titan generation and, like several primordial figures, an Oceanid, in the sense that Mètis was born of Oceanus and Tethys, of an earlier age than Zeus and his siblings. Mètis was the first great spouse of Zeus, indeed his equal (Hesiod, Theogony 896) and the mother of Athena, Zeus' first daughter, the goddess of the arts and wisdom. By the era of Greek philosophy Mètis had become the goddess of wisdom and deep thought, but her name originally connoted "magical cunning" and was as easily equated with the trickster powers of Prometheus as with the "royal metis" of Zeus.[1] The Stoic commentators allegorized Metis as the embodiment of "wisdom" or "wise counsel", in which form she was inherited by the Renaissance. Mètis was both a threat to Zeus and an indispensable aid (Brown 1952:133): Zeus lay with Metis but immediately feared the consequences. It had been prophesied that Metis would bear extremely powerful children: the first, Athena and the second, a son more powerful than Zeus himself, who would Greek deities series Primordial deities Olympians Aquatic deities Chthonic deities Other deities Titans The Twelve Titans: Oceanus and Tethys, Hyperion and Theia, Coeus and Phoebe, Cronus and Rhea, Mnemosyne, Themis, Crius, Iapetus Sons of Iapetus: Atlas, Prometheus, Epimetheus, Menoetius Personified concepts Muses Nemesis Moirae Cratos Zelus Nike Metis Charites Adrasteia Horae Bia Eros Apate Themis Eris Page 15 of 16 eventually overthrow Zeus.[2] In order to forestall these dire consequences, Zeus tricked her into turning herself into a fly and promptly swallowed her.[3] He was too late: Mètis had already conceived a child. In time she began making a helmet and robe for her fetal daughter. The hammering as she made the helmet caused Zeus great pain and Prometheus, Hephaestus, Hermes, or Palaemon (depending on the sources examined) either cleaved Zeus's head with an axe,[4] or hit it with a hammer at the river Triton, giving rise to Athena's epithet Tritogeneia. Athena leaped from Zeus's head, fully grown, armed, and armored, and Zeus was none the worse for the experience. The similarities between Zeus swallowing Mètis and Cronos swallowing his children have been noted by several scholars. The second consort taken by Zeus, according to the Theogony was Themis, "right order". Hesiod's account is followed by Acusilaus and the Orphic tradition, which enthroned Mètis side by side with Eros as primal cosmogenic forces. Plato makes poros, or "creative ingenuity", the child of Mètis.[5] Metis Metis was the Titaness of the forth day and the planet Mercury. She presided over all wisdom and knowledge. She was seduced by Zeus and became pregnant with Athena. Zeus became concerned over prophecies that her second child would replace Zeus. To avoid this Zeus ate her. It is said that she is the source for Zeus wisdom and that she still advises Zeus from his belly. It may seem odd for Metis to have been pregnant with Athena but, never mentioned as her mother. This is because the classic Greeks believed that children were generated solely from the fathers sperm. The women was thought to be nothing more than a vessel for the fetus to grow in. Since Metis was killed well before Athena's birth her role doesn't count. Metic From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search (not to be confused with Métis) In ancient Greece, the term metic meant resident alien, a person who did not have citizen rights in their Greek city-state (polis) of residence. Metic comes from the Greek μέτοικος, metoikos, where the second element is derived from οἶκος, oikos, "house; inhabit." The preceding element meta could here either carry the notion of "change" or of "among". The two possible senses implicit in the word were one who changes their place of dwelling and one who lives among (that is, who is "among" but not "of"). There is no need to distinguish between these senses. Both reflect the reality of the Page 16 of 16 immigrant—a person who has moved from somewhere else and come to live among strangers. Goddess of wisdom, warfare, handicrafts and reason. Sister of Ares, and is the Athena daughter of Zeus. Sprung from Zeus's head in full body armor. She is the wisest of the gods. Her symbols are the aegis, owl, and olive tree. God of fire and the forge (god of fire and smiths) with very weak legs. He was thrown off Mount Olympus as a baby by his mother and in some stories his father. He makes armor for the gods and other heroes like Achilles. Son of Hera Hephaestus and Zeus is his father in some accounts. Married to Aphrodite, but she does not love him because he is deformed and, as a result, is cheating on him with Ares. He had a daughter named Pandora. His symbols are an axe, a hammer and a flame. 1 . I use Enquiry rather than Inquiry in line with British-Australian English convention. The Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at La Trobe is conducting a university wide pilot of EBL in 2008-9, based on the Manchester ‘hub and spoke’ model; the University of South Australia features a commitment to EBL in its teaching and learning framework, while Macquarie University lists PBL workshops as one of its Learning and Teaching Plan strategies for improving the research skills and critical thinking of students. The Australian Learning and Teaching Council sponsored national Teaching-Research Nexus project cites numerous examples of PBL-EBL practice in Australian departments on its website. 3 Gallop, J. (1994) “The Teacher’s Breasts”, in Jill Julius Matthews, ed. Jane Gallop Seminar Papers, Humanities Research Centre A.N.U. See also responses by Moira Gatens, Vicky Kirby and Meaghan Morris. 4 Gallop J. (1997). Feminist Accused of Sexual Harassment, Duke University Press. 5 We have had our own case in Australia of a woman academic being accused of sexually harassing her female students - this was in a Western Australian university in the department of Archeology, part of the saga known as the Rindos affair. Some of you may have heard of this from the newspapers a few years ago. 6 Arendt, H. ‘Crisis in Education’ in Between Past and Future, Penguin 1993 7 Gordon, M, ed. (2001). Hannah Arendt and Education: Renewing our Common World, Boulder, Colo., Westview Press 8 Derrida, J. (2004) Dissemination, trans. Barbara Johnson. Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 153 9 Baert, P. and Shipman, A. (2005) ‘University Under Siege? Trust and Accountability in the Contemporary Academy’ European Societies 7(1): 157-185 10 Davis, Robert A ‘Erotapokriseis: Questioning, answering and the representation of the teacher in Byzantine pedagogy’, paper delivered to The Teacher: Image, Identity, Icon. An International Conference exploring representations of 'The Teacher' in the Arts and Humanities (2 to 4 July 2008, Glasgow, United Kingdom). 11 McGovern, Deirdre, ‘The teacher as host’, paper delivered to The Teacher: Image, Identity, Icon. An International Conference exploring representations of 'The Teacher' in the Arts and Humanities (2 to 4 July 2008, Glasgow, United Kingdom). 12 Morrison. Harriet B (1988) Seven Gifts A New View of Teaching Inspired by the Philosophy of Maurice Merleau Ponty. Northern Illinois University Educational Studies Press. 13 . see Wirzba, Norman ‘From maieutics to metanoia: Levinas's understanding of the philosophical task’ Man and World Volume 28, Number 2 / April, 1995; and ‘Teaching as propaedeutic to religion: The contribution of Levinas and Kierkegaard’ International Journal for Philosophy of Religion Volume 39, Number 2 April, 1996 14 Arendt, H. (1978). Life of the Mind, London, Secker and Warburg. 2