V. Open Educational Resources - Computer Networks Laboratory

advertisement

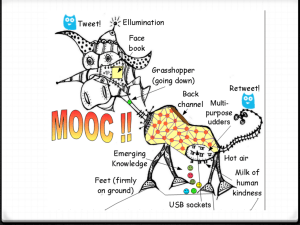

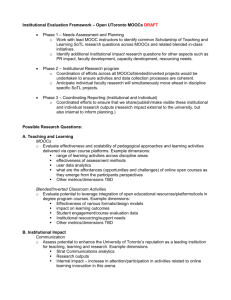

Open Education K. Pisutova ** Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia Empire State College, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA Katarina.Pisutova@esc.edu Abstract— Introduction to some concepts of openness in education. This presentation addresses concepts of Open Licensing (Creative Commons licenses), Open Content, Open Coursewere, Open Educational Resources, and Open Teaching (Massive Open Online Courses – MOOC). The presentation loosely follow structure of David Wiley’s Introduction to Openness in Education course[1], but chooses areas to focus on. The main focus is kept on open teaching and Massive Open Online Courses. I. INTRODUCTION Openness and sharing has always been part of education process. Sharing knowledge is the very definition of education. In his TEDxNYED presentation [2], David Wiley compares sharing in education to overcoming our inner two-year old, screaming “MINE!”. However, society’s proprietary rules encourage our inner two-years old. And even in education, where sharing should be the core of the process we have rules, it encourage us not to share knowledge freely. Internet gave us means for easy and immediate sharing of knowledge and within the last decade movement for more openness and sharing is gaining wide support in education including changes in institutional approaches and policies of many universities. Empire State College (ESC) decided to join the movement. ESC became a founding anchor partner in the OER University (OERu). A Learning Resources task force (which I was a member of) was created in fall 2011, to investigate the possibilities of using these emerging open resources within the ESC courses and for other open learning initiatives. In an effort to familiarize themselves with terms and concepts and to explore the issues related to open resources, in Spring 2012 the members of the task force went together as a group through open course on Openness to Education taught by David Wiley [1]. This is an open course, consisting of 12 topics: Open Licensing, Open Source, Open Content, Open Courseware, Open Educational Resources, Open Access, Open Science, Open Data, Open Teaching, Open Assessment, Open Business Models and Open Policy. Each topic contains video and text resources. Participants maintain personal blogs and are required to post a blog article reflecting on each of the topics. Final blog article should contain links to each of the topic article and after instructor’ review of all the articles, participants can receive course completion badges. We proceed through the course as a group, met physically every two weeks, reviewed video resources together and discussed and analyzed issues arising within each topic. This article briefly summarizes key issues from the course, provides links to course resources, as well other resources on the topics. However, I pick and choose topics of interest, so this article doesn’t provide full summary of the course. I also focus a lot on issues that raised from our discussions, as well as discussions from different conferences, where we as a group presented summaries of issues studied in the course. II. OPEN LICENSING Open licensing was the first topic of the course and it also was the only one focusing more on regaining practical skills in being able to recognize and use Creative Commons licenses. Video resource for this part is TEDx speech by Lawrence Lessig [3], where he clearly explains why licenses that allow sharing, re-using and modifying work of others are necessary for creativity. He uses Walt Disney and his most famous classic movies (such as Cinderella, Snow White and Sleeping Beauty) as an example of extraordinary work of using and remixing work of others. Unfortunately later Disney Company made sure that nobody else can do to them what they did to brothers Grimm. Unfortunately, recent copyright laws are rather restrictive in copying, distributing, editing, remixing and building upon work of others. Creative Commons licenses are a way for creators to allow others to copy, distribute, edit, remix and build upon their work still within copyright laws. Basic description of licenses could be found on Creative Commons website [4]. The course’s website also provides link to a Creative Commons License game [5]. Understanding licenses means knowing how to use them and this game is a perfect tool to make us realize it is not simple. III. OPEN SOURCE AND OPEN CONTENT Concept and reality of open source software has been around for a while. Some 15 years ago, open source software was not extremely user friendly comparing to commercial products and was considered used exclusively by computer geeks. Times have changed, for instance Moodle increases its share of the Learning Management Systems market, has most language mutations, user friendliness is comparable and there are free tutorials and instructions to be found for each and every feature. Similarly open content is not anymore just stuff nobody would buy anyway. In an effort to define open content, Wiley [6] uses analogy of an open door. It can be opened fully or just half-way or just tiny bit, but it is still not closed. The same way, open content can come with no restrictions or some restrictions for its free use. However, the primary permissions for open content usage are based on "4Rs Framework:"[6] 1. Reuse - the right to reuse the content in its unaltered / verbatim form (e.g., make a backup copy of the content) 2. Revise - the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language) 3. Remix - the right to combine the original or revised content with other content to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup) 4. Redistribute - the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend) IV. OPEN COURSEWARE In 2001, MIT made a groundbreaking decision to publish content of their courses online. At the time, they made it clear [7], that they are giving away materials, not the education. According to one faculty member at the press conference in 2001 [7], "raw material is not true education." Open CourseWare (OCW) isn't replacing traditional course work at MIT. According to the faculty panelists, a "true" MIT education comes from the interaction of the students with faculty, students with students, students with lab work and equipment, facilities, community, etc. Another way to think of OCW is as a publication, rather than a form of distance learning. It is material; not instruction. MIT was then quickly followed by the launch of similar projects at Yale, the University of Michigan, and the University of California Berkeley and many more educational institutions around the world. Open Courseware Consortium now unites over 200 institutions from over 40 countries around the world [8] with materials from thousands of courses accessible. V. OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Most current definition of Open Educational Resources (OER) according to UNESCO[9] is: “Open Educational Resources are digitised materials offered freely and openly for educators, students and selflearners to use and re-use for teaching, learning and research.” So as opposed to OCW here we are talking not just about materials from college courses, but any and all educational materials and resources. OER movement got support from private donors such as Open Society Institute or Shuttleworth Foundation, international organizations like UNESCO and government policies. Amount of OER online can be a bit overwhelming. The source we as a group found very useful is the OER Handbook [10]. VI. OPEN TEACHING MOOC – a Massive Open Online Course is a next step beyond providing course content and resources. MOOCs are courses provided by universities a student can take for free. The MOOC is defined as follows [11]: The course is open (all work is done where people can read and comment on it) The course is cost free (you can take it without paying for participating in the course – payment for credit is possible though) The work in the course is shared with all the people taking it The course is participatory – you gain by engaging with other people’s work (there usually aren’t specific assignments, but engagement with other people and materials) The course is distributed (all participant’s blogs, discussions and contributions are part of the course, but don’t reside on the same website) The first MOOC was taught by David Wiley at Utah State University in 2007. This was a graduate course in open education that was opened to participation by anyone around the world. About 50 people from eight countries participated. In 2008 George Siemens from Athabasca University and Stephen Downes from National Research Council in Canada run another open online course called “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge”. In this course participated 25 tuition-paying students at the University of Manitoba and 2,300 people all over the world who took the class free of charge. The term MOOC was also introduced with connection to this course [12]. More courses with increasing numbers of students followed. In the fall 2011 over 160,000 people signed up for a Stanford University’s course in Artificial Intelligence. At the Beginning of 2012 two private educational companies - Coursera and Udacity (both started by Stanford University professors) and non-profit initiative Edx (common project of MIT and Harvard University) focusing on MOOCs were launched. MOOC development seems to go in two different directions. One is represented by earlier MOOCs based on connections, social networking and interaction – these courses are called cMOOC and one is represented by Coursera courses, referred to as xMOOC. George Siemens [13] explains the difference between the two: “our cMOOC model emphasises creation, creativity, autonomy and social networking learning. The Coursera model emphasises a more traditional learning approach through video presentations and short quizzes and testing. Put another way, cMOOCs focus on knowledge creation and generation whereas xMOOCs focus on knowledge duplication”. He notes that in time the xMOOCs “may well address the “drill and grill” instructional methods that are receiving some criticism”. Coursera gains new partnerships very fast. According to an article from September 19, 2012 [14], Coursera announced new partnership with 16 universities worldwide to help them produce MOOCs. This more than doubles the number of their institutional partners and pushes number of Coursera courses over 200. However, even though Coursera claims to be for-profit company, so far they haven’t started making a profit. According to Daniel [15] Coursera lists 8 possible business models at the end of their institutional agreements: Certification (students pay for a badge or certificate) Secure assessments (students pay to have their examinations invigilated (proctored)) Employee recruitment (companies pay for access to student performance records) Applicant screening (employers/universities pay for access to records to screen applicants) Human tutoring or assignment marking (for which students pay) Selling the MOOC platform to enterprises to use in their own training courses Sponsorships (3rd party sponsors of courses) - Tuition fees. According to Young [16] certification and employee recruitment are under the most active consideration. VII. MYTHS AND ISSUES ABOUT MOOCS Involvement of top US universities into offering MOOCs brought media attention and significant increase in attendance. With such a stir, inevitably myths developed even though MOOCs have been around for a relatively short time. Following analysis of issues is mainly based on Daphne Koller’s (one of the Coursera founders) presentation [17], article by John Daniel [15] and blog entry by Tony Bates [18]. A. Access to Education in Developing Countries Argument, that MOOCs will resolve issues with access to education in developing countries seems to be used quite often. However, US universities partnering with Coursera don’t offer credits or degrees for completions of their MOOC courses. These MOOC courses offer interesting alternative to people who are seeking knowledge, but not credits or degrees. This is not true for majority of population in developing countries. B. Quality Issues The second myth is that a course from good and famous university is always a good course. Not necessarily. The elite universities that are starting to offer xMOOCs en masse gained their reputations in research. This doesn’t say anything about their abilities of online teaching. For face-to-face as well as traditional online courses, the drop-out rates are significant in quality assessment. MOOCs with their less than 10% completion rate would not score very high in this sense. Methods to assess quality of MOOCs still need to be developed. C. Computers Personalize Learning One of the largest problems with online learning in general (and one of the causes of large drop-out rates) is that students feel alone and abandoned without feeling personal attention of their instructor. However cleverly constructed assessment program still won’t give student a feeling, that there is somebody on the other side who pays attention to them personally and who might get disappointed if they drop out. This has been researched on traditional online learning where average class sizes are about 15 students per instructor [20]. With thousands students in a MOOC course students are essentially on their own, communicating with computer program and (if course structure calls for it) with their classmates. VIII. POSSIBILITIES AND FUTURE OF MOOCS At this time MOOCs are fashionable and institutions are flocking into the business. Even though nobody has yet figured out how to make MOOCs profitable or at least financially sustainable. Some of MOOC ventures will probably go down, some might survive. They are bringing new options and opportunities for people who desire knowledge without needing degrees. If institutions work out systems and open ways to gaining credits for MOOCs cheaper than for traditional education, this might open more affordable ways to college degrees. However, due to their massive character, their completion rates might stay as low as they are and only most motivated and self-sufficient students would succeed. But on the other hand – from my personal point of view – there are courses out there on topics I am interested in taught by professors who are renowned in the field – and they are free. There is nothing wrong with that. This article is a very incomplete overview of issues in and around openness in education. I picked and chose information and topics that felt interesting and relevant for me and for this conference. For more complete overview take the David Wiley’s open course on openness in education. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Thanks to members of OER Task Force 2011/2012 at the Empire State College Ellen Murphy, Joyce McKnight, Claire Miller, Hui-Ya Chang, Robert Kester, Rebecca Bonanno, Katarina Pisutova, Suzanne Hayes, Xenia Coulter, Michele Ogle, Deb Staulters REFERENCES [1] [2] Wiley, D. (2012) Openness in Education http://openeducation.us/ Wiley, D. (2010) Open Education and the Future. TEDx presentation, June 23, 2010 http://youtu.be/Rb0syrgsH6M [3] Lessig, L. (2010) Open Licensing. TEDx presentation, March 6, 2010 http://youtu.be/FhTUzNKpfio [4] Creative Commons (2012) About the Licenses http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ [5] BYU Independent Study (2011) Finding and Using Open Educational Resources http://indstudy1.org/univ/355460515034/Flash/Lesson2/PracticeV ersion.html [6] Wiley, D. (2011) Defining the “Open” in Open Content http://opencontent.org/definition/ [7] Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2001) Open Courseware Press Conference, April4, 2001 http://youtu.be/4XFvqOSRsa8 [8] OCW Consortium (2012) Website of Open Courseware Consortium http://ocwconsortium.org/ [9] Hylén, J. (2006). Open Educational Resources: Opportunities and Challenges. OECD http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/37351085.pdf [10] Gurell, S & Wiley, D. (2008). OER Handbook for Educators http://wikieducator.org/OER_Handbook/educator_version_one [11] Cormier, D. (2010) What is MOOC? http://youtu.be/eW3gMGqcZQc [12] Wikipedia (2012) Massive Open Online Courses http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MOOC [13] Siemens, G. (2012) MOOCs are really a platform. eLearnspace. http://www.elearnspace.org/blog/2012/07/25/moocs-are-really-aplatform/ [14] Kolowich, S. (2012) MOOC Host Expands, Inside Higher Education http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/09/19/courseradoubles-university-partnerships [15] Daniel, J. (2012) Making Sense of MOOCs: Musings in a Maze of Myth, Paradox and Possibility http://sirjohn.ca/wordpress/wpcontent/uploads/2012/08/120925MOOCspaper2.pdf [16] Young, J. R. (2012). Inside the Coursera Contract: How an Upstart Company Might Profit from Free Courses, Chronicle of Higher Education, July 19 http://chronicle.com/article/How-an-UpstartCompanyMight/133065/?cid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en [17] Koller, D. (2012) TED Talk, June 2012 http://www.ted.com/talks/daphne_koller_what_we_re_learning_fr om_online_education.html [18] Bates, T. (2012) What’s right and what’s wrong about Courserastyle MOOCs, Blog entry, August 5, 2012 http://www.tonybates.ca/2012/08/05/whats-right-and-whatswrong-about-coursera-style-moocs/ [19] Knox, J., Bayne, S., Macleod, H., Ross, J. & Sinclair, C. (2012). MOOC Pedagogy: the challenges of developing for Coursera. http://newsletter.alt.ac.uk/2012/08/mooc-pedagogy-thechallenges-of-developing-for-coursera/ [20] Moore, M.G. & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance Education: A Systems View, Belmont, USA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.