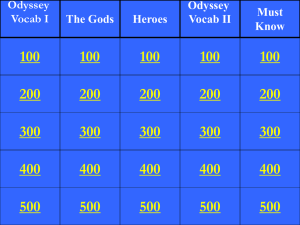

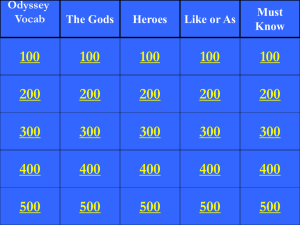

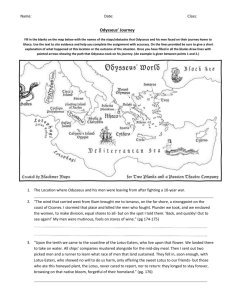

Lectures on the Odyssey

advertisement