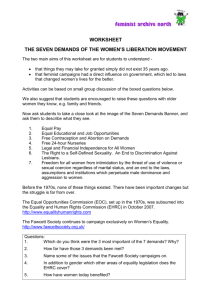

Promoting equality in pay

advertisement