Interdisciplinarity is a word that has been heard a lot on campus

advertisement

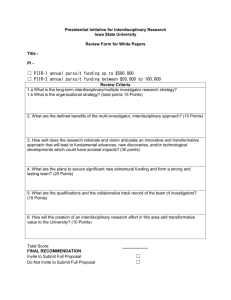

Submission to Curriculum Reform Committee, 14 February 2008 Dr Hazel Hutchison, School of Language and Literature Interdisciplinarity is a word that has been heard a lot on campus recently in connection with the process of Curriculum Reform, and there had been considerable discussion about the possibility of cross-school and cross-college courses taught across disciplinary and administrative boundaries. This presentation outlines one such course already running successfully: EL40BL Frankenstein to Einstein: Literature and Science in the Nineteenth Century. This course is taught by myself, Hazel Hutchison, based in the School of Language and Literature, Ben Marsden and Ralph O’Connor, based in the School of Divinity, History and Philosophy, with input from Neil Curtis and Siobhan Convery in Historic Collections. The nineteenth century is a long and diverse period, but 10-15 minutes is a very short period, so this presentation will give a brief sketch of what we do in this course. I will start by outlining our Aspirations for this course: Why did this course seem necessary? What are the key ideas which govern its conception? Then I will give you some of the Practicalities: How is this course delivered? What do the students learn and what do they take away from it? Finally I want to draw a few Abstractions: What can be translated from our experience into the context of other courses? At a moment of change, what might be relevant to Curriculum Reform? Aspirations Like all great ideas Frankenstein to Einstein began with a cup of coffee. When Ben Marsden and I were office neighbours in the Old Brewery, we quickly worked out that we had a shared interest in nineteenth-century culture, and had more intellectual common ground than many of our colleagues in our own departments. At some point over a cup of coffee, we rather wistfully agreed it would be good to teach a course which utilised my expertise in literature and his expertise in history of science. However, the administrative procedures in place made this less than easy. Everybody we consulted told us that this would be technically possible but fraught with administrative problems—an assessment that was borne out by later experience. However, ‘technically possible’ provided enough of a green light for us to proceed, and Ben and I produced a course proposal and started thinking about course content. At this point Ben secured a Senior Research Fellowship at the Dibner Institute (MIT/Harvard) for a year and plans were shelved. This turned out to be a useful holdup, as in the interval the School of DHP hired Ralph O’Connor, a specialist in nineteenth-century popular scientific literature. Ralph was keen to be involved in the project, so we reorganised the course programme to include him. When Ben returned from Boston we clarified our objectives and procedures, and the course was ready. Interdisciplinarity is nothing new. In fact, in the history of thought, it is disciplinarity that is the parvenu upstart. Certainly in the nineteenth century many discipline boundaries that seem cast-iron to us simply did not exist. This was true within academia and beyond. One need only glance at the contents page of any major nineteenth-century periodical to see this interdisciplinary process at work. Take for example a volume that happens to be on my bookshelf, Nineteenth Century, vol. 2 (1877). In this volume, articles on History, Theology, Foreign Policy, Medicine, Optics, Education, Literary Biography, Housekeeping, Philosophy, Technology and Poetry all rub shoulders. W. K. Clifford, Professor of Mathematics at University College London, writes on poetry, while W. E. Gladstone, MP, serving Prime Minister, writes about the optics of colour. However, many modern academic approaches to the nineteenth century are so focused on disciplinary methods and concerns, that the richness of this cultural diversity is made invisible to students. The main aim of our course is to expose students to the interdisciplinary nature of nineteenth-century culture, so that their understanding of texts, events and practices from the period is enlivened and sharpened. We also want to question their own intellectual boundaries and enhance their reading strategies by exposing them to different kinds of texts. For the cultural history students enrolled on the course, this means learning to examine imaginative literary texts as cultural documents. For the literature students it means reading scientific and journalistic texts as literary texts in their own right—texts which employ complex linguistic strategies and rhetorical structures. Every nineteenthcentury text on this course has the status of a ‘primary text’, and should be read with as much attention to its mode of expression as to its content. Indeed, as recent thought acknowledges, it is never possible to separate these two elements completely. By the end of the course, the students should have grasped not only that many nineteenth-century literary texts are crammed with references to contemporary scientific developments and technological innovations; but also that the science of the century was shaped by the cultural imperatives of the period, and were disseminated and popularised through the sophisticated use of tropes and narrative structures by writers in many different contexts. (See Powerpoint slides for a list of course aims.) Practicalities EL40BL is taken by students from English and Cultural History. Technically it is also available to History students, it has never been enthusiastically advertised to History students. As with all level-4 English courses, the course is taught in two two-hour seminars each week, and is capped at 15 students. Both years it has been offered, it has been the most heavily subscribed course at level 4. The course could run twice over if we had the time to teach it. This is a team-taught course, but this doesn’t just mean we rotate the teaching. Our aim is to have two of us there for most of the seminar sessions. This does not always register on our workloads, but it really works in class and is one of the aspects of the course which the students enjoy most. They especially relish any hint of disagreement or diversity of opinion on some fine academic point. And, at level 4, it is healthy for the students to be exposed to a variety of contrasting intellectual ideas. The reading for the course is a mix of literature and contemporary source material. Each week a ‘literary’ text is balanced with some other primary text and the students are encouraged to explore the connections between them and are given the necessary contextual information to facilitate this. The course also includes visits to the Archives, at Special Libraries to look at relevant print and MS material and to Marischal Museum where the scientific, anthropological and ‘imperial’ collections enhance the students’ engagement with the core themes of the course. The students write an essay mid-term; they also take a two-hour exam in January. 10% of the course mark is allocated for seminar participation and 10% for a group project. Last year, this project was based on the invaluable nineteenth-century periodical collection in QML basement, and explored subjects including the popularisation of scientific culture, the impact of print technology on literary practice, and popular medical literature. This year, the students are working with Neil Curtis at Marischal Museum to design an exhibition which will be staged in June and July 2008. Before Christmas, the students gave presentations outlining their ideas. In the coming months they will be working with Neil and the course team to realise exhibitions based on the themes of Science and Religion, the Human Animal, Time and Technology. Abstractions What is to be learned from this empirical experiment in interdisciplinary teaching? Teaching across intellectual and administrative boundaries can be exciting and rewarding for both students and staff. EL40BL has now run twice and has been very popular with the students. It has also been a joy to teach. Teaching across a disciplinary boundary means always being on the edge of one’s intellectual comfort zone. However, teaching within a team means constantly supporting one another, sparking new ideas and learning from each other. Feedback from the students, both written and verbal, suggests that they enjoy exposure to a mix of approaches and opinions. They also appreciate the opportunity to explore new territory, perhaps because they have reached a stage where they feel secure within their original discipline. The students also love getting out of the classroom and learning through material objects, including original printed material. For the subject area of nineteenth-century culture this interdisciplinary format is particularly appropriate. However it does requires a certain amount of disciplinary focus in order to retain an appropriate level of academic rigour and analysis. The students studying English and those studying Cultural History certainly get different things out of the course, which suggests that they need the intellectual security of some sort of disciplinary training, and some sense of a final disciplinary objective, in order to do useful business with other kinds of materials and subject areas. The danger of too much interdisciplinary teaching within a degree programme is that students could lose a sense of focus for their learning and develop into graduates who know a little about a lot, but have few intellectual tools to analyse any of it thoroughly. Encouraging the students to make use of analytical processes from single disciplines helps to counter this danger. It is also intriguing to notice how cautious the students can be about crossing discipline boundaries. Of course, EL40BL is designed to challenge that, but many of the literature students clearly want to continue reading the literary texts as literature and the other texts as secondary context. They clearly enjoy the security of knowing what they are doing and how, and I think it is important not to freak them out by shattering the analytical methods and categories which they have learned. Engaging in the traditions and methods of a single academic discipline remains a worthwhile project. Specialisation leads to depth and rigour of thought and often does evolve eventually into an interest in how the structures of one discipline also apply elsewhere. There is no point in attempting to rush students through this process. Learning is an incremental process and there are few shortcuts. Sound knowledge of one area is essential before attempting knowledge of many areas, if one is to develop any idea of how to recognise sound knowledge—which should be the goal of any academic programme. Finally, a few words about structures and funding. Winston Churchill is quoted as saying about the layout of the Houses of Parliament: ‘We shape our buildings and thereafter they shape us.’ Something similar is true of university structures. The frustrations of running this course have all been administrative and structural. Although I am not fully qualified to speak about the evolution of Cultural History, I do know that English Literature is, and always has been, a very interdisciplinary discipline. However, the institution of a school structure at Aberdeen has, ironically, not enhanced the possibilities for interdisciplinary collaboration, or synergies, with other departments. The current orientation of the school structure has focused money and attention on one aspect of the many interdisciplinary facets of English, and has inevitably hampered the growth of its connections elsewhere. Intellectual links with Divinity, History and Philosophy and with the Social Sciences have become hard to sustain. It certainly takes some determination to keep such connections alive across fiscal boundaries. The History Department has been reluctant to sign up singlehonours History students to the course, despite frank negotiations early on to ensure that the course was accredited to that programme as well as to Cultural History. This leads to an imbalance of FTEs between the two schools, and inevitable concerns about funding and staffing in the future. Moreover, raising money for innovative teaching events and practices, such as the forthcoming exhibition at Marischal, is always complex when designated funds for such events do not exist. As this course has a foot in several camps, and as few resources are available for teaching projects rather than research, this can prove rather tricky. Like any worthwhile project, interdisciplinary courses require solid resources, and cannot run entirely on enthusiasm. If such courses are to be at the foreground of a radical rethink of the curriculum, this may have also radical implications for administrative and fiscal structures. Interdisciplinary teaching is challenging and rewarding for both staff and students alike. An interdisciplinary course such as EL40BL Frankenstein to Einstein works best for students when attached to a programme with a robust disciplinary methodology, so that the students can explore new territory using tried and tested intellectual strategies. However, the current administrative and fiscal structures of the University do not make interdisciplinary teaching straightforward, and if such courses are to form a component of the reformed curriculum then issues of funding and registration will need to be resolved. HH 14 February 2008 / revised 11 March If you have any questions about this presentation, you can contact Hazel Hutchison at h.hutchison@abdn.ac.uk