Information Structure in English

advertisement

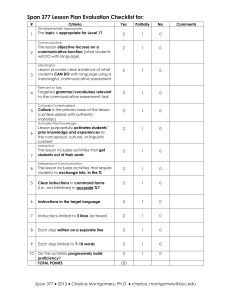

MA Applied Linguistics Mohammad Al Towaim Information Structure in English Contents Introduction 1 Section 1: Rewrite the given text considering the information structure 2 1.2 Rewrite the given text and made comments 2 Section 2: Communicative Principle affecting the structuring of Information 3 2.1 Given-New Information (Principle of End-Focus) 3 2.1.1 Given Information 3 2.1.2 New Information 3 2.2 Principle of End-Weight 4 2.3 Principle of Clausal-Initial 5 Section 3: Some of the grammatical Devices For Reordering Information 6 3.1 Thematic Reordering 6 3.2 Postponement 6 3.2.1 Postponing parts of the sentence elements 7 3.2.2 Postponing the emphatic Reflexive Pronoun 7 3.3 Subject-Complement Switching 7 3.3.1 Subject-Verb Inversion 7 3.3.2 Subject-Operator Inversion 8 3.4 Passivization 9 3.4.1 Passivization without an agent 9 3.4.2 Passivization focusing on the other elements 10 3.4.3 Passivization with an agent 10 3.5 Cleft-Sentence 10 3..6 Pseudo-Cleft Sentence 11 3.6.2 The differences between Cleft-Sentences and Pseudo-Cleft Sentence 12 3.6.3 Major communicative Functions of Pseudo-Cleft Sentence 13 3.7 Extrapostion 13 3.8 Existential 14 Conclusion 15 References 16 Appendix 17 Introduction In the light of communicative considerations, information structure plays a significant role within English grammar and discourse. Rather than hesitating when we face various choices among different styles, knowledge of information structure allows us to arrange our messages in an appropriate way. I have chosen this topic for these reasons and in order to be able to apply such features to my native language, Arabic, whose grammar studies do not appear to refer to them. This essay will consider the information structure of English by starting with the given text and mentioning some communicative changes which I will make. In Section 2, the communicative principles affecting a choice of different information styles will be considered, before Section 3 examines the grammatical devices available in English with suitable examples, either from the given text, or from other sources. Finally, the conclusion will summarise the essay and pose some questions relating to my postgraduate study. This essay focuses on written rather than spoken language, for two reasons. Firstly, the availability of time in a conversation, according to Greenbaum (1991), is generally very limited, and I think, as a result, that the opportunity to take account of information structure is likely to be quite narrow. Secondly, in spontaneous utterances, speakers may emphasise or highlight certain elements using various devices such as tone, stress and intonation, which are, in my opinion, not related directly to the chosen topic. Section 1: Rewrite the given text 1 to improve the information structure Sentences 1 Comments See Appendix, p17 1 1 There is a man in the bar of the Phoenicia By using Existential ‘There’, the hotel who gave me some incorrect theme (a man) containing new information. information was moved out of subject position, since the subject is new. 2 He was a fattish pinkish man in bulging To respect the principle of End- blue short. Focus, the information is reordered. 3 What he was looking for was a decent Here, Pseudo-Cleft is used to place to stay, so he informed me. focus on the new information as complement of verb to be ‘was’ 4 He had investigated the Channel Islands, The long clause is moved to end Bermuda, Jamaica and Geneva, and none position by Fronted Topic. had proved satisfactory. 5 6 It is Malta where he was now, among A Cleft-Sentence is used here to Malts. emphasis ‘Malta’ I always picked the wrong man at the bar To respect the principle of EndFocus, the information is reordered. 7 I had done it again. The adverb again was moved to the end position to respect EndFocus principle. 8 His fat eyes were now focused on me no need for any unusual structure Section 2: The Key Communicative Principles affecting Information Structures. According to Leech and Svartvik (1975), the majority of foreign students learning English are interested in making use of language communicatively. Therefore, it is 2 important to consider the communicative principles affecting the order of information within and between clauses. Such principles relate to meaning, situation and use. The most significant principles in English are: 2.1 The Given-New principle (Principle of End-Focus) The information in a message can be divided into given and new information: 2.1.1 Given information ‘Given’ information is what the speaker/writer supposes the hearer to know about. Such information is considered as given, either in the light of the situation or because it has been mentioned before. 2.1.2 New information New information, on the other hand, is the part of the message which is assumed to be new for the hearer/reader. Thus, it should receive the main focus among all parts of the message, called ‘end-focus’. The main aim of this principle is to order the message to emphasise the new information by putting it at the end of the sentence or clause. Consider the example below, which is adapted from the given text: Given information New information He was a fattish pinkish man in bulging blue shorts. In this sentence, the pronoun ‘he’ refers to someone who is already known, so it is placed at the beginning of the sentence, while the rest of the sentence is new information, since it carries more details regarding the man. It is important to say that although the elements occurring at the end of a sentence typically deserve the end-focus, there are some elements in language which are inherently given, even though they might occur in final position. Halliday (1991) gives examples of anaphoric elements (those that refer to things mentioned before) and deictic elements (those that are interpreted by reference to the ‘here-&-now’ of the discourse. 3 2.2 The principle of End-Weight It is normal in English to put long and complex constituents at the end of a clause, because this makes them easier to understand. Consider the following examples: (a) That he did not understand what I said at the lecture is very strange! (b) It is very strange that he did not understand what I said at the lecture. It is clear, for communicative purposes, that (b) is more appropriate than (a), since the former has a long, complex phrase in subject position, and that may make it difficult to interpret. The principle of end-weight, as (Greenbaum 1991) mentions, usually has a strong relationship with the principle of end-focus, in which the most significant information is likely to occur at the end of the clause. However, the two principles can conflict, as can be seen in the examples below: (a) My father owns the largest betting-shop in London. (b) The largest betting-shop in London belongs to my father. Leech and Svartvik (1975) note that in (a), the long object phrase comes after the short subject ‘my father’, to respect the principle of end-weight. In contrast, this principle is broken by putting the long phrase in (b) in the theme position; but it could be said that the writer did so to apply the principle of end-focus to ‘my father’. 2.3 The principle of Clause-Initial Topic/Topic Preservation As we have just seen, the two principles of end-focus and end-weight give importance to the final position of the sentence or clause. Nevertheless, the first position is also important for communication, due to the fact that the first element is the ‘point of departure’ for what the speaker/writer wants to say. We call this element the ‘theme’ (Downing and Locke 2000). 4 Usually, but not always, theme corresponds with ‘topic’, which indicates what the text, or part of the text, is about. Downing and Locke (2000) claim that there are three types of topic, which may be illustrated by the phrase below: …buying a caravan… The ‘superordinate topic’ is the topic of the whole text, whereas the ‘basic-level topic’ is a participant in the phrase (in this case, the buyer, the seller, the caravan or the money). A ‘subordinate topic’ is part of the basic-level topic, such as some part of the caravan. Such principles may influence the selection of one structure over another, in which the topic tends to be expressed as the first element in the sentence/clause (Collins and Hollo 2000). Section 3: Some Grammatical Devices for Reordering Information The previous section set out some of the principles affecting the choice of information structure in English. Now, the logical question is: how can we apply those principles? Some answers are offered below. 5 3.1 Thematic Reordering According to Leech and Svartvik (1975), English allows elements other than the subject to be chosen as topic. This process involves moving that element to the front of the sentence. So, as we have seen above, a less important idea is shifted, and the principle of end-focus can be applied. In English, such a shift, called ‘topic fronting’, has three different effects: An ‘emphatic topic’. This kind of fronted topic is common in informal conversation. In such cases, a speaker tends to front a complement (e.g. ‘Joe’, ‘his name is’). It seems that the speaker says the most significant thing first, thus giving it double emphasis. A ‘contrastive topic’. Here, we can contrast two things mentioned in the previous clause (e.g. ‘Rich, I may be!’ in answer to ‘You’re rich, so you must be happy.’) This type of fronted topic is not very common, and is used in rhetorical style. ‘Given topic’. Consider this example: ‘Most of these problems a computer could solve easily’. Here, the object is moved to the initial position as a fronted topic to give more focus to the subject. However, the topic still receives partial emphasis, since it is the starting-point of the sentence (Leech and Svartvik 1975). 3.2 Postponement There are many types of postponement, two of which are: 3.2.1 Postponing Part of the Sentence If we have a long noun phrase, we can postpone a part of the sentence to avoid awkwardness, by splitting, for instance, an adjective from its postmodifiers (Leech and Svartvik 1975). Consider the following examples: (a) How ready to make peace with their enemies are they? (b) How ready are they to make peace with their enemies? 3.2.2 Postponing the Emphatic Reflexive Pronoun 6 If a reflexive pronoun occurs as part of the subject, it is likely to be postponed in the light of the end-focus principle: John himself told me. → John told me himself. (= ‘It was John, and no one else, who told me’.) 3.3 Subject-Complement Switching In English, fronting is not applied to the topic element only; the verb phrase, or part of it, can occur before the subject. This kind of fronting is called ‘inversion’ or ‘subjectcomplement switching’. There are two types of such processes: ‘subject-verb inversion’ and ‘subject-operator inversion’, which can be explained as follows: 3.3.1 Subject-Verb Inversion According to Leech (1975), subject-verb inversion is usually identified by two main features: The verb phrase consists of a single verb word. This verb is an intransitive verb of position (be, stand, lie, etc) or a verb of motion (come, go, fall, etc). The example below illustrates these features: Subject Verb The rain came down in torrents This sentence is changed by subject-verb inversion to: Down came the rain in torrents. 3.3.2 Subject-Operator Inversion This kind of subject-complement switching applies in questions. Moreover, Greenbaum and Quick (1990:410) point out some common circumstances when the operator precedes the subject: 7 When a negative element is fronted for emphasis: Not a car did he own. Under no circumstances must the door be left unlocked. In comparative clauses, when the subject is not a personal pronoun: Oil costs less than would atomic energy. In subordinate clauses of condition and concession, especially in formal usage: Even had she left a will, it is unlikely that the college would have benefited. Moreover, the principle of end-focus by subject-operator inversion can be applied to ‘so’, with the meaning of ‘degree’ or ‘amount’ (Leech and Svartvik 1975): So absurd did he look that every one stared at him. (= ‘He looked so absurd that…’) 3.4 Passivization Consider the examples below: (a) The teacher gave the lecture. (b) The lecture was given by the teacher. If we analyse the active clause (a) and the passive clause (b) deeply, it can be said, according to Collins and Hollo (2000), that the passive form can be derived by: Converting the object of the active (the lecture) into the subject if the passive; Making the subject of the active (the teacher) into the axis of the byphrase; Making the VP passive, by adding auxiliary be to VP before the main verb and converting the main verb into the Ven form. 8 The usage of the passive form is one of the grammatical devices available in English, and plays a significant role in applying communicative principles such as end-focus and end-weight. Passivization can be divided into three types: 3.4.1 Passivization without an agent For communicative considerations, particularly the principle of end-focus, a passive form is preferred when we aim to omit the agent. Greenbaum and Quick (1990:45) point out some reasons for such usage in detail: We do not know the identity of the agent of the action. We want to avoid identifying the agent because they do not assign or accept responsibility. We feel that there is no reason for mentioning the agent, because identification is unimportant or obvious from the context. In scientific and technical writing, writers often use the passive to avoid the constant repetition of the subject I or we, and to put the emphasis on the process and procedure. This use of the passive helps to give the writing the objective tone that such writers wish to convey. 3.4.2 Passivization focusing on the other elements According to Downing and Locke (1992), a significant proportion of passive clauses in English have an adjunct, a complement or a prepositional object in end-position, as in these examples: He was taken to jail. Nothing has been heard of him for months. The letters had been sent unstamped. Membership is limited to the over-65s. The retiring chairman was presented with a gold watch. In these passive examples, it could be said that the end-focus would have applied if the verb had been active. Instead, the passive form was used to respect the principle of ‘clausal-initial topic'. Then, the preferred theme may be affected and given 9 information (‘he’, ‘The letters’), a nuclear negative (‘nothing’) a nominalization (‘membership’) or recipient (‘the retiring chairman’) would be chisen. 4.4.3 Passivization with an agent The two types above show cases where the agent is omitted. On the other hand, English sometimes prefers the ‘by-agent’ passive (Leech and Svartvik 1975; Downing and Locke 1992), for one or more of three main reasons: To consider the agent as new information. To respect the principle of end-weight. To retain the same subject throughout the sentence. 3.5 Cleft Sentences Although their grammatical structure seems to be difficult, cleft sentences are easy to interpret, because they place a clear emphasis on the person or thing that is being referred to. In order to make an utterance more easily understood, cleft sentences consist of two parts: 1) the ‘empty’ subject pronoun ‘it’ followed by the verb to be and its complement; then 2) a relative clause. This is illustrated in the example below: empty theme + verb to be + complement relative clause It was Mark that won the car Cleft sentences are used to draw special attention to the new information involved, usually in the first part. However, the relative clause in the second part carries some of the emphasis, since it is the antecedent element (Collins and Hollo 2000). We can refer to some notes on usage which are made by Downing and Locke (1992): Who or that, but not which, are fronted in the second part; and that is more common than who, even after proper names. Relative adverbs (where, how and when but not why) can be placed at the beginning of the second part. 10 The cleft sentence receives a special significance in the written language, because it helps the reader to identify more easily the position of the focused element, without the need for other devices such as underlining or capitals. 3.6 Pseudo-Cleft Sentences Another device which can be used to re-order the information in the English clause is the Pseudo-Cleft Sentences. Identified Identifier What he clearly hates are lies This sentence is typical, according to Collins and Hollo (2000), following the SVC pattern, and has a nominal relative clause as subject or complement. In this form, we can distinguish between two parts, ‘identifier’ and ‘identified’. The identifier usually receives the focus of information, even if the order is reversed, as in the following sentence (Downing and Locke 1992): Identifier identified Lies are what he clearly hates 3.6.1 Differences between Cleft Sentences and Pseudo-Cleft Sentences Greenbaum (1991), Greenbaum and Quick (1990) and Downing and Locke (1992) indicate three main differences between these two grammatical devices: The emphasized parts are different. In a cleft sentence, the first part is more important than the second, while it is the second part of a pseudocleft which has the stronger focus. Unlike the cleft sentence, the pseudo-cleft sentence can emphasise a prediction, action or event, in sentences like: 11 What he’s done is spoil the whole thing. What he did was rent a car. What we should all do is hurry off home. The pseudo-cleft sentence is more limited than the cleft-sentence, in that it is always constructed with a what-clause, whereas the latter is more flexible in the use of relative adverbs. However, the two types are similar from another point of view, since the highlighted element must be appropriate to the situational context. 3.6.2 Communicative functions of the Pseudo-Cleft Sentence This device has three functions in discourse, mentioned by Downing and Locke (1992:250): It can introduce a new topic: What we shall consider today is the Second World War. It can recall an earlier part of the discourse: We arrived home to find the place flooded; what had happened was that a pipe had burst. It can provide contrast with a previous statement or question: - Do you mean that we should go now? - No, what I meant was that we should finish quickly. 3.7 Extraposition When we have a long subject clause, we can apply the principles of end-focus and end-weight by extraposition, which can be achieved by moving the long subject clause to the end of the sentence and replacing it by ‘it’. Such movement takes various forms (Collins and Hollo 2000; Downing and Locke 1992): Finite Subject Extraposition: (Finite that-clause). 12 That he escaped without injury is amazing → It is amazing that he escaped without injury. Finite Subject Extraposition: (Finite WH-clause): How much that child eats is unbelievable → It is unbelievable how much that child eat. Non-Finite Subject Extraposition: To think of a convincing excuse is difficult → It is difficult to think of a convincing excuse. Object Extraposition: I find that he drives without a license amazing → I find it amazing that he drives without a license. This is usually obligatory with finite and non-finite clauses. 3.8 Existential there English has an alternative way to structure information communicatively, by use of the unstressed dummy pronoun there followed by a verb, usually be, and a nominal group. Consider the first sentence in the given text: There is a man in the bar of the Phoenicia hotel who gave me some incorrect information. The sentence above without existential there would be gauche, since ‘man’ seems to be new information. In this regard, the subject moved by there is usually indefinite. Thus, as Downing and Locke (1992) point out, there typically has a function in which the indefinite subject is shifted to a later position, in the light of either the end-focus or the end-weight principle. This device can express events, happenings and states of affairs. In such cases, the noun is a nominalization of a process (Downing and Locke 1992): 13 There was a sudden feeling of panic. Moreover, according to Collins and Hollo (2000) and Downing and Locke (1992), existential sentences permit few verbs to follow presentative there; examples include remain, appear, follow, seem, arise, rise and emerge. 14 Conclusion Some aspects of information structure in English have been considered, in terms of both the principles controlling a selection of utterance styles and of the communicative devices applying to such choices. As I said above, this topic is significant for me as a teacher of Arabic to foreign students, given the lack of this kind of study in Arabic. Thus the question arises of whether such analyses are applicable to any language, and if so, how they can be applied to Arabic. I hope to find some answers in future research. 15 References Collins, P & Hollo, C (2000) English Grammar: An Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave. Downing, A & Locke, P (1992) A University Course in English Grammar. London: Prentice Hall International. Ferguson, G. (2005) Handout: ‘Lecture on Information Structures’. University of Sheffield. Greenbaum, S & Quick, R (1990) A Student's Grammar of The English Language. Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman. Greenbaum, S (1991) An Introduction to English Grammar. Essex: Longman Group Limited. Halliday, M A K (1985) An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Bury St Edmunds: St Edmundsbury Press Ltd. Leech, G & Svartvik, J. (1975) A Communicative Grammar of English. London : Longman 16 Appendix The given text: (2) The man in the bar of Phoenicia hotel gave me some incorrect information. (2) A fattish pinkish man in bulging blue short he was. (4) A decent place to stay was what he was looking for, so he informed me. (4) The Channel island, Bermuda, Jamaica and Geneva had already been investigated by him and none had proved satisfactory. (5) In Malta he was now, among Malts. (6) The wrong man at the bar was what I always picked and (7) again I had done it. (8) It was his fat eyes that were now focused on me. The text after rewrite: There is a man in the bar of the Phoenicia hotel who gave me some incorrect information. He was a fattish pinkish man in bulging blue short. What he was looking for was a decent place to stay, so he informed me. He had investigated the Channel Islands, Bermuda, Jamaica and Geneva, and none had proved satisfactory. It is Malta where he was now, among Malts. I always picked the wrong man at the bar, and I had done it again. His fat eyes were now focused on me 17