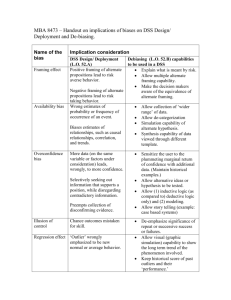

Cheung_Honors_Thesis_FINAL

advertisement

Affect and Framing 1 Running head: AFFECT AND RISK-SEEKING IN THE FRAMING EFFECT I’m feeling lucky: The relationship between affect and risk-seeking in the framing effect Elaine Cheung Cornell University Affect and Framing 2 Abstract The present research explored the role of affect in the framing effect. In Study 1, participants provided affect ratings during a gambling task. Positive affect was found to be associated with risk-seeking in the loss frames; affect was not related to behavior in the gain frames. In Study 2, participants were either instructed to make their decisions in the gambling task using emotions (emotion-focused condition) or without using emotions (emotion reappraisal condition). Participants in the emotion-focused condition displayed the classic pattern of the framing effect. Conversely, participants in the emotional reappraisal condition displayed reduced risk seeking in the loss frames and greater risk aversion in the gain frames. These findings suggest affect is related to risk-seeking in the framing effect. Affect and Framing 3 I’m feeling lucky: The relationship between affect and risk-seeking in the framing effect The way information is presented can largely impact one’s judgments and decisions. For instance, the presentation of the outcomes of a cancer treatment in terms of mortality or survival may largely influence one’s decision whether or not to accept the treatment. It is important, therefore, to understand the processes behind people’s susceptibility to information presentation and how this may influence their decision behavior. Decision research has largely focused on cognitive explanations for biases in judgments and decision making (e.g., Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993). However, there has been recent attention highlighting the importance of affect in guiding decision behavior (Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001; Slovic, Fincuane, Peters, & Macgregor, 2002). In the present research, we seek to explore the role of affective processes in one notable decision bias, the framing effect. The “framing effect” (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981) is the tendency for people to make systematically different decisions based on whether alternatives are framed positively (i.e., as gains) or negatively (i.e., as losses). When alternatives are framed positively, individuals are more likely to display risk aversion, preferring to choose options with certain outcomes over those that are risky. Conversely, when alternatives are framed negatively, individuals are more likely to display risk-seeking behavior, preferring risky options over a sure loss. That is, individuals are more likely to choose to keep a “sure thing” in decisions framed as gains and gamble in decisions frames as losses, in spite of the decisions being objectively equivalent. The classic paradigm used to demonstrate the framing effect is the “Asian Disease Problem”, a hypothetical scenario created by Tversky and Kahneman (1981): Affect and Framing 4 Imagine that the United States is preparing for an outbreak of an unusual Asian disease that is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are as follows: Problem 1(Positive Frame): If Program A is adopted, exactly 200 people will be saved. If Program B is adopted, there is a 1 in 3 probability that all 600 people will be saved and a 2 in 3 probability that no people will be saved. Which of the two programs would you favor? Problem 2 (Negative Frame): If Program C is adopted, exactly 400 people will die. If Program D is adopted, there is a 1 in 3 probability that nobody will die and a 2 in 3 probability that all 600 will die. Which of the two programs would you favor? When presented with options framed positively (i.e., as lives saved), people overwhelming choose Program A (i.e., the sure option). Conversely, when presented with options framed negatively (i.e., as lives lost), people overwhelming choose Program D (i.e., the risky option). This pattern consistently emerges, despite the fact that the expected outcomes of all four programs are equivalent. Prospect Theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) is a cognitive theory of decision making under risk and uncertainty that has been used to explain framing. According to Prospect Theory, the value of an option is defined in terms of gains and losses. Rather than considering the final outcomes of a decision, people tend to assign value to gains Affect and Framing 5 and losses and use decision weights instead of probabilities to make their decisions. Moreover, the theory suggests that people tend to underweigh outcomes that are probable in favor of outcomes that are certain (the certainty effect) and generally discard components that are shared by all options under consideration (the isolation effect). These tendencies are represented in the form of an s-shaped value function in which the function is concave for gains (implying risk aversion), convex for losses (implying risk seeking), and steeper for losses than for gains (implying loss aversion). Although Prospect Theory offers a compelling explanation for decision making in the framing effect, affective processes may also be influencing these decisions. We believe a consideration of the role of affect in framing may help provide a more comprehensive understanding of decision making in the framing effect. Affect in Risky Decision Making Affect has been shown to be instrumental in guiding decisions. Loewenstein et al. (2001) assert the importance of affect in risky decision making through their “risk as feelings” model. According to this model, individuals react to the prospect of risk at both a cognitive level and an emotional level. Although the two levels are interrelated, they can diverge from one another. When this divergence occurs, affective reactions often supersede cognitive interpretations in influencing risky decision behavior. Similarly, the “affect heuristic”, proposed by Slovic et al. (2002), asserts the importance of using affect in guiding decisions. The authors argue that using affective impressions to make judgments can be more quick and efficient than using a deliberative strategy such as weighing the pros and cons of each option, particularly in complex and uncertain circumstances. Affect and Framing 6 The authors extend the affect heuristic to risky decision making suggesting that an individual’s affective impression of an option should directly inform his or her judgments of risk and benefit in the option (Slovic, Finucane, Peters, & MacGregor, 2004). Specifically, a positive view of an option should lead an individual to judge the risks of that option as low and the benefits of that option as high whereas a negative view of an option should lead an individual to judge the risks of the option as high and the benefits of the option as low. Accordingly, affect likely plays an important role when making framing decisions. For example, people may have different affective reactions to the prospect of risk in alternatives framed as gains or losses, and these reactions may lead to different choices by frame. Additionally, people’s affective reactions to each option may influence their judgments of both the risks and benefits in the options. These judgments of risk and benefit may also lead them to different choices based on frame. Thus the pattern of riskseeking in loss frames and risk aversion in gain frames is likely influenced by different affective responses to the gain and loss frames. Evidence for Affect in the Framing Effect There is some preliminary empirical evidence for affective processes in framing behavior. De Martino, Kumaran, Seymour, and Dolan (2006) conducted a neuroimaging study of a monetary gambling task and found that behavior consistent with framing effect (specifically risk-averse behavior in gain frames and risk-seeking behavior in loss frames) was associated with greater activity in the amygdala, a brain region associated with emotional processes. This association between framing and neural activity in the amygdala suggests that affect may play an important role in the framing effect. Affect and Framing 7 Moreover, the authors found that greater activity in the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex, brain regions associated with deliberative processes, was associated with a reduced display of framing. Although these findings offer support for an association between affect and the framing effect, a direct test is needed to elucidate the specific nature of how affect may influence decision making in the framing effect. Current Project The purpose of the present research was to investigate the role of affect in the framing effect. In Study 1, participants provided affect ratings when making framing decisions in a computerized gambling task. Study 2 sought to determine whether increasing or decreasing reliance on emotion would influence framing. Participants in this study were given instructions manipulating their reliance on emotion when making decisions in the computerized gambling task. Study 1 In the present study, we sought to determine the role of affect in the framing effect. Participants in this study completed the monetary gambling task from the aforementioned De Martino et al. (2006) study adapted to include a measure of affect. We chose to use a monetary gambling task as opposed to hypothetical vignettes such as the Asian Disease Problem because we believe that the decisions within a monetary gambling task would be less abstract, more familiar, and more personally relevant to participants. In the control condition, participants completed the original task from De Martino et al. (2006). In the affect-probe condition, participants completed the same task with the addition of providing affect ratings before each decision. Affect and Framing 8 We predicted that participants in both the affect-probe and the control conditions would display classic framing (i.e., risk aversion in the gain frames and risk seeking in the loss frames). We also expected affect ratings to be a significant predictor of behavior consistent with the framing effect. As this is the first direct test to our knowledge of the relationship between affect and the framing effect, we did not include specific hypotheses regarding affect valence, and its interaction with frame, in influencing decisions in the framing effect. Method Participants Sixty-four undergraduate students (age range: 18-23; M=19.27, 38 females and 26 males) participated in exchange for course credit. Measures Positive and Negative Affect Schedule- State Version (PANAS-S; Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A., 1988). The PANAS-S is a twenty-eight item measure of current state affect. Participants were given instructions to rate the extent they were currently feeling each of the emotions listed on a 5-point scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Averages of positive and negative items were calculated to obtain a mean positive score and mean negative score for each participant. Stimuli Gambling Task. The computerized, monetary gambling task adapted from De Martino et al. (2006) consisted of 96 gambling trials: 32 gain frames, 32 loss frames, and 32 catch trials. Each trial in the study consisted of four components. Participants were first given a hypothetical endowment of money, ranging from $25 to $100 in increments Affect and Framing 9 of $25. Then, they were presented a choice situation in which they had to choose between a sure option and a gamble option: they could either choose to lose/keep a certain amount for sure (the sure option) or choose to gamble on a set probability of retaining the full amount (the gamble option). Both options were displayed simultaneously on the computer screen with the sure option always positioned on the left and the gamble option always positioned on the right. In the gain frames, sure options were presented in terms of keeping a set proportion of the initial endowment; conversely in the loss frames, sure options were presented in terms of losing a set proportion of the initial endowment. The gamble options were presented as pie charts depicting the probability of keeping or losing the full endowment. Probabilities in the gamble option ranged from 20% to 80% in increments of 20%. Notably, the expected outcomes of the sure option and the gamble option were always equal. (See Figure 1.). The catch trials were identical to the framing trials with the exception that the expected outcome of the sure option and the gamble option were not held constant; rather, the expected outcome was skewed so that there was a clear “correct” response. In these trials, the sure options were always presented as keeping/losing 50% of the initial endowment and the probabilities in the gamble options were always either a 95% or 5% chance of keeping/losing the entire endowment. An example catch trial would be a choice between keeping $50 of the $100 endowment for sure versus gambling with a 95% chance of keeping the entire $100 endowment. The purpose of these trials was to ensure that participants were engaged in the task. Affect and Framing 10 Before making each decision, participants in the affect-probe condition responded to the probe “How do you feel about this decision?” by indicating their response on a 7point Likert-type scale from -3 (very negative) to +3 (very positive) on labeled keys on the keyboard. The choice situation was presented on the screen as participants responded to the affect probe. Participants in the control condition were not presented with any probe. Finally, all participants made their choice of a sure option or a gamble option by pressing ‘z’ for the sure option and ‘m’ for the gamble option. Again, the choice situation remained on the screen as participants made their decision. Apparatus The gambling task was presented to participants on a 17” LCD screen using a Dell Optiplex GX270 desktop with E-Prime experimental software. Participant responses were recorded via a standard keyboard. Procedure The complete duration of the experiment lasted 30 minutes. Participants were run in groups ranging from one to four persons. Upon arrival, participants were seated in front of a computer and told they would be completing a computerized gambling task. Before beginning the task, participants completed the PANAS-S measure of their baseline affective state. Participants then completed the aforementioned gambling task. Each participant was randomly assigned to either the affect-probe condition or the control condition. In order to ensure the task was personally meaningful, participants were informed that they would receive a sum proportional to their total winnings at the end of the study. Affect and Framing 11 Upon completion of the task, participants once again completed a PANAS-S measure of their current affective state. All participants were then rewarded their “winnings”. Participants were then debriefed about the study and thanked for their time. Results The dependent variable for this study was calculated as the percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option in the gain and loss frames. We used 50% as an indicator for risk neutrality, with percentages significantly above 50% indicating riskseeking behavior and the percentages significantly below 50% indicating risk-averse behavior. Effects of Condition To determine whether participants differed between the affect-probe and control conditions in the percentage of trials they chose the gamble option, we conducted a 2 (condition: affect-probe vs. control) by 2 (frame: gain vs. loss) Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on the percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option. We found that there was no significant difference by condition in the percentage of trials the gamble option was chosen (F(1, 62) = .115, ns, ƞ² = .001). There was a significant effect of frame, such that the gamble option was chosen less frequently in the gain frames (42.5%) than the loss frames (57.6%) across both conditions (F (1, 62) = 18.2, p < .001, ƞ² = .128). Importantly, there was no significant frame by condition interaction (F (1, 62) = .002, ns, ƞ² = .000). (See Figure 2.). Seeing as both groups did not differ in the percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option in the gain frames and the loss frames, we can assume that the affect-probe did not alter decision making in this task. The Framing Effect Affect and Framing 12 We then investigated whether the percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option was consistent with the pattern of the framing effect. One sample t-tests were conducted to explore whether the percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option in each frame differed significantly from a risk-neutral score of 50%. One-sample t-tests using 50 as the test-value showed that in the gain frames, participants were significantly more likely than chance to choose the sure option t(63) = -3.29, p < .01, suggesting risk-aversion. Furthermore, in the loss frames, participants were significantly more likely than chance to choose the gamble option, t(63) = 2.86, p < .01, suggesting risk-seeking behavior. This pattern of risk-aversion in the gain frames and risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames is consistent with the pattern in the framing effect. Affect Ratings Predicting Choice in Each Frame To determine the influence of affect ratings on decision making, we conducted a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) analysis in the gain and the loss frames. The GEE controls for within-cluster correlation in regression models with binary outcomes. In this task, participants completed 96 repeated trials; the GEE takes into consideration repeated measures of binary outcomes within individual participants. Choice in each trial resulted in a binary outcome of either the sure option or the gamble option; for this analysis we coded choice of the sure option as 0 and the gamble option as 1. Moreover, affect ratings were treated as a continuous variable in this model with higher responses indicating higher levels of positive affect. In the gain frames, the relationship between affect ratings and the likelihood of choosing the gamble option was not significantly related, χ² (1, N = 1024) = .071, ns. Participants displayed equal levels of risk aversion regardless of their affect ratings, β = Affect and Framing 13 .018, SE = .07 (see Figure 3). However, in the loss frames, the relationship between affect ratings and the likelihood of choosing the gamble option was significantly related, χ² (1, N = 1024) = 5.89, p < .05. As seen in Figure 3, the percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option varied as a function of affect only in the loss frames, such that greater positive affect was associated with an increased likelihood of choosing the gamble option, β = .176, SE = .07. Mean Affect Ratings Mean affect ratings did not differ depending on frame; participants reported feeling slightly positive in both gain (M =. 25, SD = .98) and loss (M = .07, SD = .89) frames, t(62) = .731, ns. PANAS-S Scores We calculated mean positive and negative scores for each participant’s pre-andpost task PANAS-S measures. To test for changes in participants’ affective state, we conducted paired samples t-tests to compare mean PANAS-S scores before and after the gambling task. Participants’ PANAS-S scores did not differ as a function of condition; participants in both affect-probe and control conditions felt equally positive before and after the task, ts(32) = -.23 and -.21 respectively, ns , and participants in both affect-probe and control conditions felt equally negative before and after the task, ts(32) = -.43 and 1.04 respectively, ns. Discussion The purpose of Study 1 was to determine the role of affect in the framing effect. We found that participants in both the affect-probe and control conditions showed classic framing, namely, risk aversion in the gain frames (choosing the gamble option below Affect and Framing 14 50% of the time), and risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames (choosing the gamble option above 50% of the time). This pattern is consistent with previous findings of the framing effect (e.g. De Martino et al, 2006; Kahneman & Tversky, 1981, 2000; Kuhberger, 1998). Moreover, we found that the relationship between affect and framing was limited to the loss frames, such that risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames is predicted by positive affect. However, Study 1 did not allow us to determine the directionality of the relationship between affect and choice. Although our affect-probe preceded participants’ choice between the sure option and the gamble option, we cannot be certain that they had not already made their decision, and that their affect ratings were a result of their feelings about their choice instead of their affective responses to the decision. Thus, it remains unclear as to whether the affect ratings in this task were influencing participants’ decisions or whether their decisions were influencing affect ratings. We addressed this question in Study 2 by including a manipulation of emotion reliance in decision strategy. If framing can be altered by manipulating emotion reliance in decision strategy, then it suggests that the directionality of the effect should be affect influencing decisions rather than decisions influencing affect. Study 2 In the present study, we sought to determine whether framing could be altered by manipulating participants’ reliance on emotion when making framing decisions. Participants in this study completed a gambling task identical to the one in Study 1 with the addition of an emotion reliance manipulation. Namely, participants were instructed to either use their emotions when making decisions (emotion-focused condition) or to Affect and Framing 15 reappraise the choice situation such that they made their decisions without using emotions (emotion reappraisal condition). The strategy used in the emotion reappraisal condition is derived from Gross (2002)’s description of reappraisal as a cognitive emotion regulation strategy which involves reinterpreting a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in non-emotional terms. Based on the findings in Study 1, we predicted that participants in the emotion-focused condition would display classic framing; we also predicted that participants in the emotion reappraisal condition would display the classic pattern of risk aversion in the gain frames, but they would display reduced risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames. Method Participants Forty-three undergraduate students (age range: 18-23; M = 19.7, 27 females and 16 males) participated in a gambling study for payment of $5 or course credit. Measures, Stimuli, and Procedure The measures, stimuli, and procedure were identical to Study 1 with the exception of including an emotion reliance manipulation. Participants were randomly assigned to either an emotion-focused condition or an emotion reappraisal condition. Before beginning the task, participants were given instructions designed to manipulate their reliance on emotion when making decisions. In the emotion-focused condition, participants were given the following instructions: As you make each decision, let your EMOTIONS guide your choice. Please use the following steps to make each decision: First, consider how you POSITIVE or NEGATIVE you FEEL about each option. Affect and Framing 16 Finally, make your choice using your emotions to guide you. The instructions for the emotion reappraisal condition were adapted from the reappraisal instructions given to participants in Gross (1998). The emotion reappraisal instructions were as follows: As you make each decision, DO NOT let your emotions influence your choice. Instead, please use the following steps to make each decision. First, consider how you feel about each option. Second, REEVALUATE the options in a manner that reduces your emotions. Finally, make your choice WITHOUT using your emotions. After making each decision, all participants responded to the emotion reliance query, “How much did your emotions influence your decision” by indicating on a 7-point Likert-type scale their response from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Very much so) on the keyboard. Similar to the affect-probe in Study 1, the options remained on the screen while participants responded to the query. This query was used both as a prompt to reinforce participants’ assigned emotion reliance strategy and also as a manipulation check. Results Effects of Condition To determine whether participants differed between conditions in the percentage of trials they chose the gamble option, we conducted a 2 (condition: emotion-focused vs. emotion reappraisal) by 2 (frame: gain vs. loss) ANOVA on the percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option. We found that there was a significant difference in the percentage of trials the gamble option was chosen based on condition (F(1, 41) = 11.71, p < .001, ƞ² = .30). Participants in the emotion-focused condition were Affect and Framing 17 significantly more likely to chose the gamble option (50.5%) than participants in the emotion reappraisal condition (38.7%). There was also a significant effect of frame, such that the gamble option was chosen less frequently in the gain frames (42.5%) than the loss frames (50.9%) across both conditions (F (1, 41) = 13.23, p < .001, ƞ² = .338). Lastly, there was no significant frame by condition interaction (F(1, 41) = .075, ns, ƞ² = .002). (See Figure 4.). The Framing Effect The percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option in the gain and loss frames for both conditions is displayed in Figure 4. To determine whether the participants’ behavior was consistent with the pattern of the framing effect, we conducted one-sample t-tests using a risk-neutral score of 50% as the test-value for each condition in the gain and loss frames. Participants in the emotion-focused condition were significantly more likely than chance to choose the sure option in the gain frames t(21) = -2.14, p < .05, and the gamble option in the loss frames, t(21) = 2.06, p = .05. This pattern of risk-aversion in the gain frames and risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames provides evidence for classic framing in the emotion-focused condition. For participants in the emotion reappraisal condition, we found that participants were significantly more likely than chance to choose the sure option t(20) = -4.70, p < .01 in the gain frame, suggesting risk-averse behavior. However, in the loss frames, participants in the emotion-reappraisal condition did not significantly differ from the riskneutral score of 0.5, t(20) = -1.49, ns. Thus, although participants’ risk aversion in the Affect and Framing 18 gain frames was consistent with the framing effect, their risk neutrality in the loss frames was inconsistent with the framing effect. Emotion Reliance Response After each decision, participants responded to an emotion reliance query asking, “How much did your emotions influence your decisions?” on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 7(Very much so). To determine whether mean responses to this query differed by condition, we conducted a 2(condition: emotion-focused vs. emotion reappraisal) by 2(frame: gain vs. loss) ANOVA on participants emotion reliance responses. As expected, participants significantly differed by condition in emotion reliance responses (F(1, 41) = 175.32, p < .001, ƞ² = 182.35). Frame was not a significant predictor of emotion reliance, (F(1, 41) = .106, ns, ƞ² = .11). Lastly, the interaction between frame and condition were also not significant (F(1, 41) = .009, ns, ƞ² = .009). (See Table 1). Furthermore, we conducted a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) analysis in the gain and the loss frames for each condition to determine whether reliance on emotion was related to the likelihood of choosing the gamble option. Similarly to Study 1, we coded choice of the sure option as 0 and the gamble option as 1. Moreover, emotion reliance responses were treated as a continuous variable with higher responses indicating increased emotion reliance. Emotion reliance responses were significantly related to the likelihood of choosing the gamble option for participants in the emotion-focused condition in the gain and loss frames, χ² (1, N = 704) = 37.40 and 13.42 respectively, ps < .001, such that higher emotion reliance responses were associated with a greater likelihood of choosing the gamble option in both the gain and loss frames, βs = .41 and .26, SEs = .07 and .07 respectively. Likewise, in the emotion reappraisal condition, Affect and Framing 19 emotion reliance responses were significantly related to the likelihood of choosing the gamble option in the gain and loss frames, χ² (1, N = 672) = 16.01 and 10.14 respectively, ps ≤ .001; higher emotion reliance responses were also associated with a greater likelihood of choosing the gamble option in both the gain and loss frames, βs = .27 and .18, SEs = .07 and .06 respectively. (See Figure 5.). PANAS-S Scores We calculated mean positive and negative scores for each participant’s pre-andpost task PANAS-S measures. To test for changes in participants’ affective state, we conducted paired samples t-tests to compare mean PANAS-S scores before and after the gambling task. Similar to Study 1, participants’ PANAS-S scores did not differ as a function of condition; participants in both conditions felt equally positive before and after the task, ts(41) = 1.16 and .05 respectively, ns , and participants in both conditions felt equally negative before and after the task, ts(41) = -1.56 and -.78 respectively, ns. Discussion The purpose of Study 2 was to explore the effect of manipulating emotion reliance in decision strategy on framing behavior. We found that participants in the emotion-focused condition showed classic framing behavior, namely, risk-aversion in the gain frames and risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames. This is consistent with our findings in Study 1, as well as with previous studies of the framing effect (e.g. De Martino et al, 2006; Kahneman & Tversky, 1981, 2000; Kuhberger, 1998). Consistent with our hypothesis, participants in the emotion reappraisal did not display framing behavior in the loss frames; the percentage of trial participants chose the gamble option was not significantly different from a risk-neutral score of 50%. This Affect and Framing 20 finding that risk-seeking behavior in the loss frame is not present when making decisions without using emotions provides further support for Study 1’s finding that the primary role of affect in the framing effect lies in the loss frame. However, participants in the emotion reappraisal condition displayed significantly greater risk-aversion than participants in the emotion-focused condition; because of this difference in the gain frames between conditions, we cannot assume that the risk-averse behavior in the emotion reappraisal condition is truly consistent with classic framing. An alternative explanation for our findings could be that by decreasing the reliance on emotion when making decisions, we increased overall risk aversion in the emotion reappraisal condition for both the gain frames and the loss frames. This second explanation is further supported by our finding that higher emotion reliance responses were associated with increased risk seeking in both conditions in the gain frames and the loss frames. A limitation of the present study is that we did not include a control condition without any instructions. However, based on our findings in Study 1, increasing the salience of affect (through an affect probe) did not influence participants’ decisions in the gambling task. Similarly, we believed that a reliance on emotion when making decisions would not alter participants’ decisions in this task. We attempted to address this limitation by comparing the results in the present study with the results from Study 1. We found that the emotion-focused condition did not differ from either the affect-probe or control conditions in Study 1, suggesting that an emotion-focused strategy is relatively comparable to participants’ naturalistic strategy when making framing decisions. Furthermore, the emotion reappraisal condition, when compared with the affect-probe Affect and Framing 21 and control conditions in Study 1, showed similar findings as when compared with the emotion-focused condition in Study 2. The emotion reappraisal condition was marginally significantly different from the affect and control conditions in Study 1 for the gain frames and significantly different from the affect and control conditions in Study 1 for the loss frames. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that this study would have been strengthened with the addition of a control condition without any instructions. General Discussion The present research found a relationship between affect and risk-seeking behavior in the framing effect. Study 1found evidence for a relationship between positive affect and risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames of the framing effect. This finding is consistent with Slovic et al. (2004)’s explanation that positive affective appraisals should lead to lower perceptions of risk and higher perceptions of benefits in an option. One explanation for the association between positive affect and risk-seeking behavior could be that the gamble option in the loss frames felt more positive to participants relative to choosing a sure loss. Additionally, choosing the gamble option could also elicit positive emotions such as excitement; however, we did not find positive affect to be associated with increased risk-seeking in the gain frames. A final explanation could be that there was no true risk of loss to participants in this task; the worst possible outcome would be for participants not to win anything. Furthermore, we did not expect the finding in Study 1 that affect did not predict risk aversion in the gain frames. Perhaps risk-aversion in the gain frames is not driven by affective processes. Another explanation could be that the role of affect in the gain Affect and Framing 22 frames is more subtle in nature than that of the loss frames, and that a more nuanced approach than self-reported affect ratings is necessary. In Study 2, we found that participants in the emotion-focused condition (relying on emotions when making decisions) displayed classic framing. Conversely, participants in the emotion reappraisal condition (making decisions without using emotions) displayed increased risk aversion in the gain frames and reduced risk-seeking in the loss frames. The pattern displayed by the emotion reappraisal condition suggests that by decreasing participants’ emotion reliance in decision strategy, we increased risk-aversion in their overall decision making. Furthermore, we found that higher emotion reliance responses were associated with increased risk seeking behavior. Collectively, these findings suggest that the role of affect in the framing effect may be such that affect drives the risk-seeking behavior in this tendency. In the present research, we used a gambling task instead of hypothetical vignettes such as the classic “Asian Disease Problem” (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). We chose the gambling task because we thought monetary gambling decisions would be less abstract, more familiar, and more personally relevant to participants. However, as the gambling task consisted of 96 consecutive trials, one limitation may be the possibility that participants’ decision making may have changed over the course of the 96 trials. Additionally participants’ decisions in each trial may have been influenced by the previous trials they have been exposed to; we attempted to minimize order effect s by randomizing the order of trials. Nevertheless, future research may benefit from studying the role of affect in framing across different framing paradigms. Affect and Framing 23 One limitation of the present research is the lack of external validity in the gambling task; the task did not offer much potential gain or risk of loss to participants. While we attempted to make the experience personally meaningful to the participants by informing them that they would receive a sum proportional to their total winnings at the end of the study, the risk of loss to the participants was relatively benign. Participants did not risk losing anything in this study; the worst possible outcome would be to not receive any reward. Moreover, as this was a laboratory experiment, participants may have suspected that their potential gains were limited. Thus, the affect elicited in this experiment may not necessarily be comparable to affect elicited by true losses and gains outside of an experimental setting. This is consistent with our finding in Study 1 that mean affect, regardless of frame, did not differ a great deal from 0 (neutral). The fact that we still found significant effects for the role of affect within this experimental design is promising as one would expect the affective experience to be limited in this design relative to a real-world setting with authentic gains and losses. Another limitation is that participants were not provided feedback as to whether they “won” or “lost” each trial, yet instead made repeated decisions without receiving feedback until the end of the study. While providing feedback immediately after each trial would be more naturalistic, the feedback of “winning” or “losing” each trial would likely influence participants’ affect and their future choices, making it very difficult to study the pure mechanisms behind the framing effect. For example, Gehring and Willoughby (2002) found that when participants were provided feedback in a gambling scenario, participants that were told they ‘lost’ a trial became increasingly risky in subsequent trials to make up for their losses. Thus, we believe our decision not to include Affect and Framing 24 feedback, while less naturalistic, allows for a more controlled test of the processes in the framing effect. Future research should elucidate the role of discrete emotions underlying the framing effect. Lerner and Keltner (2000) found that fear and anger, two discrete emotions of the same valence, resulted in different appraisals of the risk perception in future events. Specifically, they found that fearful individuals judged the risk of future events as high whereas angry individuals judged the risk of future events as low. Likewise, future research may discover how discrete positive and negative emotions differentially influence risk perception in framing decisions. Moreover, the risk as feelings model (Loewenstein et al., 2001) distinguishes between anticipatory and anticipated emotions in risky decision making. Anticipatory emotions are immediate, visceral reactions to risk and uncertainties whereas anticipated emotions are emotions that are expected to be experienced in the future. Distinguishing between anticipatory and anticipated emotions in the gain and loss frames may also help clarify the influence of emotional processes in framing. An additional direction for future research may be to study the role of affect in the framing effect in different developmental populations such as children, adolescents, and older adults. The framing effect is a tendency that only develops as early as late childhood (Reyna and Ellis, 1994). Studying the role of affect in the development of this systematic bias may help shed light on both the framing effect and the development of emotional processes in decision making. Moreover, research suggests that adolescents may be more likely to consider the risks and benefits of each outcome rather than relying on heuristic strategies when making risky decisions (Reyna and Farley, 2006). Future Affect and Framing 25 research may explore how adolescents may differ in the role of affect when making framing decisions to further understand adolescent risky decision making. Lastly, Mikels and Reed (in press) found that when completing a monetary gambling task, older adults did not display the classic pattern of risk aversion in the gain frames and risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames that young adults displayed. Whereas older adults displayed similar levels of risk aversion to young adults in the gain frames, older adults did not display risk-seeking behavior in the loss frames. Investigating the role of affect in older adults’ decision making in a framing task could help explain these age differences in riskseeking behavior in the loss frames, and also could help further the understanding of the role of emotional processes in the decision making of older adults. Conclusions The present investigation explored the role of affect in the framing effect. We found that positive affect was a significant predictor of risk-seeking in the loss frames; affect was not related to risk aversion in the gain frames. Additionally, we found that relying on one’s emotions when making framing decisions leads to the classic pattern of risk aversion in the gain frames and risk seeking in the loss frames. However, using a strategy in which one does not rely on their emotions when making decisions leads to reduced risk seeking in the loss frames and greater risk aversion in the gain frames. Collectively, these findings suggest a relationship between affect and risk-seeking behavior in the framing effect. Affect and Framing 26 References De Martino, B., Kumaran, D., Seymour, B., & Dolan, R. J. (2006). Frames, biases, and rational decision-making in the human brain. Science, 313, 684-687. Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & Slovic, P. (2003). Judgment and decision making: The dance of affect and reason. In S. L. Schneider & J. Shanteau (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on judgment and decision research. New York: Cambridge University Press. Gehring, W. J. & Willoughby, A. R. (2002). The medial frontal cortex and the rapid processing of monetary gains and losses. Science. 295, 2279-2282. Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39, 281-291. Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent- and response- focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 224-237. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2000). Choices, values, and frames. New York: Cambridge University Press. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263-291. Kuhberger, A. (1998). The influence of framing on risky decisions: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75, 23-55. Lerner, J. S. & Keltner, D. (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgment and choice. Cognition and Emotion, 14, 473-493. Affect and Framing 27 Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, E. S. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267-286. Mikels, J. A., & Reed, A. E. (in press). Monetary losses do not loom large in later life: Age differences in the framing effect. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive decision maker. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Reyna, V. F. & Farley, F. (2006). Risk and rationality in adolescent decision-making: Implications for theory, practice, and public policy. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(1), 1-44. Reyna, V. F. & Ellis, S. C. (1994). Fuzzy-trace theory and framing effects in children’s risky decision making. Psychological Science, 5, 275-279. Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. An International Journal, 24, 311-322. Slovic, P., Finucane, M., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D.G. (2002). The affect heuristic. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 397-420). New York: Cambridge University Press. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 4, 249-262. Affect and Framing Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. 28 Affect and Framing 29 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Joseph Mikels for his feedback and support at every step of this process. Without his guidance, this work would not be possible. I would also like to thank Andy Reed and Dr. Marianella Casasola for their continued support and thoughtful feedback on this thesis. Special thanks to Dr. Thomas Gilovich and Dr. Valerie Reyna for agreeing to be on my defense committee; I appreciate your ideas and feedback on this research. I would like to thank the Emotion and Cognition Lab for making research a fun and delightful experience. Special thanks to Lee Kaplowitz for his programming expertise in this study. I am eternally grateful to John Rhee, Tommy Lei, Jon Hirschberger and Jade Wu for collecting this data. Finally, I would like to thank Mrs. Marjorie Corwin and Cornell University for the financial support throughout the completion of this study. This thesis was partially funded by the Marjorie A. Corwin Undergraduate Research Fellows Endowment. Affect and Framing 30 Table 1. Mean Emotion Query Responses in the Gain and Loss Frames for the EmotionFocused and Emotion Reappraisal Conditions in Study 2. Emotion-Focused Gain Loss M 4.89 4.95 SD 1.04 1.06 Emotion Reappraisal M 1.96 2.05 SD 0.95 1.02 Framing and Affect 31 Figure Captions Figure 1. Choice presentation screen of a “gain” frame; in this example, participants received an initial endowment of $25. The sure option is presented on the left side of the screen. The gamble option is on the right side of the screen with the gamble probability (80%) depicted in a pie chart. Figure 2. The percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option in the gain and loss frames for the affect-probe and control conditions. The reference line indicates a risk-neutral score of 50%. Figure 3. The percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option in gain and loss frames for negative, neutral, and positive affect ratings. The reference line indicates a risk-neutral score of 50%. Figure 4. The percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option in gain and loss frames for the emotion-reappraisal and the emotion-focused conditions. The reference line indicates a risk-neutral score of 50%. Figure 5. The percentage of trials participants chose the gamble option for each emotion reliance response collapsed across conditions. After each trial participants responded to how much they relied on their emotions when making their decision on a scale from 1(Not at all) to 7 (Very much so). The reference line indicates a risk-neutral score of 50%. Framing and Affect Figure 1. 32 Framing and Affect Figure 2. 33 Framing and Affect Figure 3. 34 Framing and Affect Figure 4. 35 Framing and Affect Figure 5. 36