Medscape 2014-02-06

www.medscape.com

The Epidemiology of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic

Encephalitis in Children

Esther Crawley

Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(2):171-174.

Abstract

Most paediatricians regularly see children with chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalitis (CFS/ME) in their clinics and yet we know little about how common it is, who is affected, whether there are risk factors and how likely a child is to recover (or what might predict recovery). Recent research suggests that this illness is more complicated than previously thought and that rather than being an illness found in middle class families, it is more common in those who are socially deprived. This article reviews what is currently known about this important but little understood condition.

The Definition

Chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalitis (CFS/ME) is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) as "disabling fatigue without another cause" that lasts 6 months with four additional symptoms. [1 2] Paediatricians in the UK use the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) 2004 recommendations [3] (adopted by National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2007 [4] ) that children should only have to wait three months before being given the diagnosis of CFS/ME. In both cases, the fatigue must be disabling and other illnesses that could explain the fatigue (such as anaemia, hypothyroidism or depression) should have been excluded. [1 4]

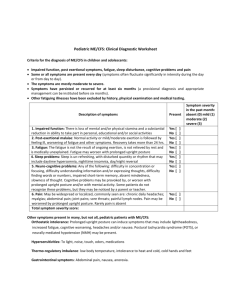

Children with CFS/ME may present with a wide range of symptoms, as described in , meaning that children may present to paediatricians with headaches or recurrent sore throats and fatigue. [5] The characteristic symptoms are postexertional malaise and unrefreshing sleep, which are almost universal. [5 6] As there is sometimes a delay before the increase in fatigue, children will describe this as being able to go to school on

Monday and Tuesday but being too unwell to go to school on Wednesday, or doing sport on Wednesday and being unable to go to school on Thursday.

Table 1. Common symptoms in addition to fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalitis

(CFS/ME) (taken from National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines Quick Reference

Guide, Box 1, page 6 4 )

Symptom

Difficulty sleeping

Muscle and/or joint pain

Headaches

Painful lymph nodes

Sore throat

Notes

Eg, insomnia, hypersomnia, unrefreshing sleep, disturbed sleep

–wake cycle multisite and without evidence of inflammation without pathological enlargement

Cognitive dysfunction

Eg, difficulty thinking, inability to concentrate, impairment of short-term memory, and difficulties with word-finding, planning/organising thoughts and information processing

Physical or mental exertion makes symptoms worse

General malaise or 'flu-like' symptoms

Dizziness and/or nausea

Palpitations In the absence of identified cardiac pathology

How many symptoms should be present to diagnose CFS/ME? The NICE guidelines suggest that one additional symptom should be present; [4] the CDC criteria require four additional symptoms, [1 2] but other criteria such as the Canadian criteria [7] require the assessment of some 65 discrete symptoms, which is a significant burden on both patients and doctors. There is currently no evidence for an obvious cut-off for the number of symptoms that define CFS/ME [6] and the approach used in NICE guidelines (just one additional symptom) to ensure that all patients should have access to services seems sensible.

Although disorders that could explain the fatigue must be excluded before a diagnosis of CFS/ME is made, some children will have other diagnoses that either do not fully explain the fatigue or would not always be associated with fatigue, and in these children, a diagnosis of CFS/ME should be considered. [1 4] For example, you should consider CFS/ME in a child with well controlled diabetes, if fatigue prevented them from attending school over a period of several months.

Are not all Teenagers Tired? What Is Different About CFS/ME?

Fatigue is common in teenagers with up to 34% of teenagers feeling 'much more tired and worn out than usual' over the last month. [8] The prevalence of fatigue increases with age during adolescence [9] and severe fatigue

(defined as more than the clinical cut-off score on the Checklist Individual Strength) is more common in teenage girls (20.5%) compared with boys (6.5%). [10]

Fatigue is also common in primary school aged children, and the reporting of fatigue in this age group has increased from 15% to 23% among 8-year-old girls and from 13% to 24% in boys between 1989 and 2005. [11]

The reason for this increase is unknown.

Although fatigue is common in teenagers, to make a diagnosis of CFS/ME, the fatigue has to be disabling and chronic. Fatigue that is sufficiently severe to stop teenagers doing activities is less common [8] as is fatigue lasting 6 months or longer. [12]

How Common Is CFS/ME?

Population surveys for CFS/ME suggest the prevalence in teenagers is between 0.4% and 2.4% [8 13 14] depending on whether the definition used is of 6 or 3 months of fatigue, respectively. The prevalence of chronic disabling fatigue, a proxy for CFS/ME in children aged 13 years old in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) cohort was 2.4% when using the 3 month definition and 0.9% when using 6 months of fatigue. [13] In this study, disability was defined as fatigue that prevented a child either attending full-time school or that had a significant impact on social or extracurricular activities. Prevalence of CFS/ME sufficiently severe to cause children to miss at least a day a week at school could be as high as 1% in children aged 11 –16. [15]

The reported prevalence of CFS/ME is much lower (0.06

–0.1%) in studies that collect data from GPs

[16] or paediatricians [17] compared with population surveys. This difference could be because children with symptomatic disabling fatigue do not access medical care or because GPs and paediatricians do not make a diagnosis. In one UK prevalence study, only 10% of children with CFS/ME had been given a diagnosis. [15] This is partly explained by the low rate (31%) of children with long-term disabling fatigue who consult a doctor. [13]

GPs are not confident in making a diagnosis of CFS/ME [18 19] and only 43% of GPs in the Netherlands will make a diagnosis in an adolescent. [17] This may explain why children and their families still experience multiple barriers in obtaining a diagnosis and accessing specialist care. [20]

Do we Know Anything About Incidence?

The estimated incidence for paediatrician-diagnosed CFS/ME is 12/100 000 adolescents (0.01%) in the

Netherlands, [17] but for the reasons described above, this may be lower than at the population level. In the UK,

4/1096 adolescents (0.36%) developed CFS (CDC definition, 6 months of fatigue and 4 symptoms) in a 4 –6 month window [8] but two of these had fatigue at the first time point and, with small numbers, the true incidence is still unknown.

Is CFS/ME One Illness?

CFS/ME is a heterogeneous condition associated with many symptoms () but with three paediatric phenotypes

(musculoskeletal, sore throat and migraine). [21] These phenotypes are not associated with length of illness

(suggesting they are not due to deconditioning), age or depression, but the migraine phenotype is associated with anxiety. [21]

Table 1. Common symptoms in addition to fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalitis

(CFS/ME) (taken from National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines Quick Reference

Guide, Box 1, page 6 4 )

Symptom

Difficulty sleeping

Muscle and/or joint pain

Headaches

Painful lymph nodes

Sore throat

Cognitive dysfunction

Notes

Eg, insomnia, hypersomnia, unrefreshing sleep, disturbed sleep

–wake cycle multisite and without evidence of inflammation

Physical or mental exertion makes symptoms worse

General malaise or 'flu-like' symptoms

Dizziness and/or nausea

Palpitations without pathological enlargement

Eg, difficulty thinking, inability to concentrate, impairment of short-term memory, and difficulties with word-finding, planning/organising thoughts and information processing

In the absence of identified cardiac pathology

Risk Factors

Gender

Female gender is a risk factor for CFS/ME in older adolescents (15 years and older) where it is 2

–3 times as common. [16 17] Gender does not appear to be a risk factor for primary school children [16] or 13 year olds [13] where CFS/ME is equally common in boys and girls. This may be because the prevalence of fatigue increases more in females as they get older than in males. [10 16 22]

Genes

Twin studies have consistently demonstrated that there is a heritable component to both fatigue [23] and

CFS/ME [24] with concordance rates of 0.55 and 0.19 in adult monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins with

CFS, respectively. [24] Heritability estimates are higher in children (MZ 0.81 and DZ 0.59), [25] which may be because children are more genetically predisposed (and therefore get CFS/ME earlier) or because children are only diagnosed because they are more severely affected.

Infection

Between 22% and 88% of children developed CFS/ME rapidly after an infection. [17 26] EBV is the most wellknown virus to cause CFS/ME with rates of 13%, 7% and 4% at 6, 12 and 24 months after infection. [27] The risk of developing CFS/ME after EBV is increased in adolescents who are female. [27] The severity of infection is an important predictor of CFS/ME rather than a specific infection. [28] This is consistent with a model where the insult acts as a trigger in a genetically vulnerable individual.

Exercise

It is not known whether exercise is a risk factor or protective for CFS/ME with conflicting evidence in adults. [29

–

31] Reduced physical activity may be associated with new onset of fatigue 12 months later [32] and with extreme tiredness occurring more than once a week in adolescents [12] but the effect on CFS/ME is not known. Both excessive exercise and sedentary behaviour are plausible risk factors and further investigation is required to understand the complex nature of exercise and fatigue.

Anxiety and Depression

Both anxiety and low mood are more common in children with CFS/ME than either healthy controls or children with other chronic illnesses. [33

–36] Teenage girls are those most likely to have a problem with anxiety, with up to

38% of those attending a specialist service scoring above the 10% upper cut-off level. [37] Depression is also common, with 29% of children with CFS/ME having probable depression. [38] These results are consistent with population studies that describe an association between anxiety and CFS/ME. [14] It is not known whether the associated mood disorders contribute to the development of CFS/ME or are caused by it. [39] There are currently no longitudinal studies that are sufficiently powered to investigate this, although several describe an association between mood disorders and later onset of fatigue. [8 12 32]

Socio-economic Factors and Family Adversity

CFS/ME used to be called 'yuppie flu'; however, the epidemiology suggests the reverse is true and that

CFS/ME is more common in those experiencing social deprivation. In the adult literature, an association with those from higher socioeconomic classes is only described for those who have successfully obtained a

CFS/ME label. [30] However, this could be explained by successful health-seeking behaviour. Studies that screen for CFS/ME report no association with social class or an association with lower social economic class.

[40 41] This suggests that CFS/ME is more common in those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds but is more likely to be diagnosed in wealthier families.

In children, family adversity in pregnancy has been shown to be associated with CFS/ME in 13 year olds. [13] In this study, family adversity was measured using a family adversity index derived from responses to questions about early childhood adversity (eg, partner aggression, substance abuse) and socioeconomic status (eg, housing adequacy, basic home amenities) completed during pregnancy (see [13] for more details). This study showed an approximately linear increase in the log odds of developing chronic disabling fatigue lasting 3 months and 6 months with increasing numbers of family adversity factors so that families with 4 factors were

2.6 times more likely to develop CFS/ME compared with families with no family adversity factors (OR of 2.56

(95% CI 1.01 to 6.45)). There are several possible explanations for this finding:

A. Family adversity could have an epigenetic effect on the developing fetus. In other words, the experience of family adversity during pregnancy could change gene expression in developing fetuses such that they were at higher risk of developing CFS/ME as a teenager.

B. Family adversity in pregnancy is likely to be associated with family adversity 10 years later, which may affect susceptibility to CFS/ME. This would be consistent with adult studies showing an association between socioeconomic status and CFS/ME in cross-sectional studies.

C. Family adversity in pregnancy may be associated with adverse events between ages 6

–8 years, which are associated with higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines at age 10 years. [42]

D. The factor providing the strongest association with CFS/ME at 13 years was maternal psychopathology (high levels of depression, anxiety or attempted suicide) in pregnancy. Maternal psychopathology may have an epigenetic effect in pregnancy or be associated with maternal psychopathology at 13 or prior to the development of CFS/ME.

Child Abuse

Retrospective case-control studies have suggested an association between childhood trauma (physical, emotional and sexual abuse, or physical or emotional neglect) and CFS/ME in adults. These studies suggest that the association could be mediated through neuroendocrine dysfunction because only those with CFS/ME and a history of abuse had decreased mean early morning cortisol levels. [43 44] However, this work needs to be replicated in a population cohort as retrospective studies may be biased and it is not clear whether the results will be relevant for CFS/ME in children as well as adults.

Maternal Risk Factors

Mothers of children with CFS/ME have higher rates of psychological distress compared with the general population. [45 46] However, as these are cross-sectional studies it is not possible to know whether this is primary or secondary to having a child with a chronic disabling condition.

Prognosis

A 1996 systematic review of prognosis, based on four small studies (N=15 –31) using different definitions of recovery, reported that 50%

–94% made a good or complete recovery at 13–72 months.

[47] A recent trial suggests that recovery rates vary between 16% and 85% depending on the treatment given. [48] For details on treatment that paediatricians should offer, see NICE guidance. [4]

The recovery in children is much better than in adults where only 22% are expected to recover with specialist treatment. [49] We do not know why children are much more likely to recover, whether different CFS/ME

phenotypes have different prognosis or whether factors thought to affect outcome in adults such as comorbid psychiatric diagnoses [47] affect prognosis in children.

What Are the Implications for Paediatricians

Paediatricians need to think about CFS/ME in children who present with a variety of symptoms (including recurrent headaches, abdominal pain, nausea and sore throats) who also have fatigue. They need to be particularly aware of CFS/ME in families from lower socioeconomic groups and be prepared to offer treatment

[4] because treatment is likely to be effective.

Those setting up services need to consider that paediatric CFS/ME is more common than previously realised and a significant number will have comorbid anxiety or low mood and need access to specialist help for this.

References

1. Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al . The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med

1994;121:953 –9.

2. Reeves WC, Lloyd A, Vernon SD, et al . Identification of ambiguities in the 1994 chronic fatigue syndrome research case definition and recommendations for resolution. BMC Health Serv Res

2003;3:25.

3. Health RCoPaC. Evidence Based Guideline for the Management of CFS/ME (ChronicFatigue

Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalopathy) in Children and Young People . London Royal, College of

Paediatrics and Child Health, 2004.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic fatigue syndrome/Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy); diagnosis and management . London, National Institute for

Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007.

5. Davies S, Crawley E. Chronic fatigue syndrome in children aged 11 years old and younger. Arch Dis

Child 2008;93:419

–21.

6. Sullivan PF, Pedersen NL, Jacks A, et al . Chronic fatigue in a population sample: definitions and heterogeneity. Psychol Med 2005;35:1337 –48.

7. Carruthers BM. Definitions and aetiology of myalgic encephalomyelitis: how the Canadian consensus clinical definition of myalgic encephalomyelitis works. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:117 –19.

8. Rimes KA, Goodman R, Hotopf M, et al . Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors for fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents: a prospective community study. Pediatrics 2007;119:e603

–9.

9. ter Wolbeek M, van Doornen LJ, Kavelaars A, et al . Fatigue, depressive symptoms, and anxiety from adolescence up to young adulthood: A longitudinal study. BrainBehav Immun 2011;25:1249 –55.

10. ter Wolbeek M, van Doornen LJ, Kavelaars A, et al . Severe fatigue in adolescents: a common phenomenon? Pediatrics 2006;117:e1078

–86.

11. Luntamo T, Sourander A, Santalahti P, et al . Prevalence changes of pain, sleep problems and fatigue among 8-year-old children: years 1989, 1999, and 2005. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:307 –18.

12. Viner RM, Clark C, Taylor SJC, et al . Longitudinal risk factors for persistent fatigue in adolescents.

Arch Pediatr Adoles Med 2008;162:469

–75.

13. Crawley E, Hughes R, Northstone K, et al . Chronic disabling fatigue at age 13 and association with family adversity. Pediatrics 2012;130:e71

–9.

14. Chalder T, Goodman R, Wessely S, et al . Epidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome and self reported myalgic encephalomyelitis in 5 –15 year olds: cross sectional study. BMJ 2003;327:654 –5.

15. Crawley EM, Emond AM, Sterne JA. Unidentified Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is a major cause of school absence: surveillance outcomes from schoolbased clinics. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000252.

16. Haines LC, Saidi G, Cooke RW. Prevalence of severe fatigue in primary care. ArchDis Child

2005;90:367 –8.

17. Nijhof SL, Maijer K, Bleijenberg G, et al . Adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome: prevalence, incidence, and morbidity. Pediatrics 2011;127:e1169

–75.

18. Bowen J, Pheby D, Charlett A, et al . Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a survey of GPs' attitudes and knowledge. Fam Pract 2005;22:389

–93.

19. Chew-Graham C, Dowrick C, Wearden A, et al . Making the diagnosis of Chronic Fatigue

Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalitis in primary care: a qualitative study. BMCFam Pract 2010;11:16.

20. Webb CM, Collin SM, Deave T, et al . What stops children with a chronic illness accessing health care: a mixed methods study in children with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis

(CFS/ME). BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:308.

21. May M, Emond A, Crawley E. Phenotypes of chronic fatigue syndrome in children and young people.

Arch Dis Child 2010;95:245 –9.

22. Ghandour RM, Overpeck MD, Huang ZJ, et al . Headache, stomachache, backache, and morning fatigue among adolescent girls in the United States: associations with behavioral, sociodemographic, and environmental factors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:797

–803.

23. Hickie I, Kirk K, Martin N. Unique genetic and environmental determinants of prolonged fatigue: a twin study. Psychol Med 1999;29:259

–68.

24. Buchwald D, Herrell R, Ashton S, et al . A twin study of chronic fatigue. PsychosomMed 2001;63:936

–

43.

25. Farmer A, Scourfield J, Martin N, et al . Is disabling fatigue in childhood influenced by genes? Psychol

Med 1999;29:279 –82.

26. Kennedy G, Underwood C, Belch JJ. Physical and functional impact of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis in childhood. Pediatrics 2010;125:e1324

–30.

27. Katz BZ, Shiraishi Y, Mears CJ, et al . Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics 2009;124:189 –93.

28. Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, et al . Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2006;333:575.

29. Harvey SB, Wadsworth M, Wessely S, et al . Etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: Testing popular hypotheses using a national birth cohort study. Psychosom Med 2008;70:488

–95.

30. Viner R, Hotopf M. Childhood predictors of self reported chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis in adults: national birth cohort study. BMJ 2004;329:941.

31. Goodwin L, White PD, Hotopf M, et al . Psychopathology and physical activity as predictors of chronic fatigue syndrome in the 1958 british birth cohort: a replication study of the 1946 and 1970 birth cohorts. Ann Epidemiol 2011;21:343

–50.

32. ter Wolbeek M, van Doornen LJ, Kavelaars A, et al . Predictors of Persisent and New-onset Fatigue in

Adolescent Girls. Pediatrics 2008;121:449 –57.

33. Carter BD, Kronenberger WG, Edwards JF, et al . Psychological symptoms in chronic fatigue and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics 1999;103:975

–9.

34. Garralda E, Rangel L, Levin M, et al . Psychiatric adjustment in adolescents with a history of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:1515

–21.

35. van Middendorp H, Geenen R, Kuis W, et al . Psychological adjustment of adolescent girls with chronic fatigue syndrome. Pediatrics 2001;107:E35.

36. Smith MS, Martin-Herz SP, Womack WM, et al . Comparative study of anxiety, depression, somatization, functional disability, and illness attribution in adolescents with chronic fatigue or migraine. Pediatrics 2003;111:e376

–81.

37. Crawley E, Hunt L, Stallard P. Anxiety in children with CFS/ME. Eur Child AdolescPsychiatry

2009;18:683 –9.

38. Bould H, Collin SM, Lewis G, et al . Depression in paediatric chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Dis Child

2013;98:425

–8.

39. Bould H, Lewis G, Emond A, et al . Depression and anxiety in children with CFS/ME: cause or effect?

Arch Dis Child 2011;96:211 –14.

40. Reeves WC, Jones JF, Maloney E, et al . Prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia. Popul Health Metr 2007;5:5.

41. Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, et al . The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: A prospective primary care study. Am J PublicHealth 1997;87:1449

–55.

42. Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, McLaughlin KA, et al . Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: a prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013;38:188 –200.

43. Heim C, Nater UM, Maloney E, et al . Childhood trauma and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome: association with neuroendocrine dysfunction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:72 –80.

44. Heim C, Wagner D, Maloney E, et al . Early adverse experience and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome: results from a population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:1258

–66.

45. van de Putte EM, van Doornen LJ, Engelbert RH, et al . Mirrored symptoms in mother and child with chronic fatigue syndrome. Pediatrics 2006;117:2074

–9.

46. Missen A, Hollingworth W, Eaton N, et al . The financial and psychological impacts on mothers of children with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME). Child Care HealthDev 2012;38:505 –12.

47. Joyce J, Hotopf M, Wessely S. The prognosis of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review. QJM 1997;90:223

–33.

48. Nijhof SL, Bleijenberg G, Uiterwaal CS, et al . Effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment for adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome (FITNET): a randomised controlled trial.

Lancet 2012;379:1412 –18.

49. White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, et al . Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome

(PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet 2011;377:823

–36.

Provenance and peer review

Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(2):171-174. © 2014 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & Royal College of Paediatrics and

Child Health