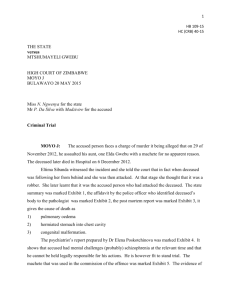

arrested, detained and accused persons

advertisement