The interdisciplinary cultural landscape.

advertisement

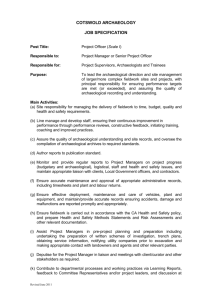

13th EAA Annual Meeting 18th -23rd September 2007 Zadar, Croatia Thematic Block: Archaeology and the Modern World: Theoretical and Mythological Perspectives Session Title: Investigating Archaeological Survey. Session Organiser: Kate Page-Smith, BA (Hons), MA, PIFA. (CgMs Consulting) Session Abstract: With a tradition stretching back over 300 years, archaeological survey and investigation deserves a definitive place within archaeological and historical research. Its multidisciplinary approach not only provides greater understanding of sites and their landscapes, but it also offers a comprehensive and cost-effective evaluation for projects. However, despite the recognised value of landscape archaeology within the heritage sector, this valuable and versatile specialism is often overlooked. For this session I would like to invite individuals to come and promote this unique discipline and its contribution towards archaeological research. With increasing emphasis upon landscape approaches and non-intrusive techniques, earthwork survey and interpretation has the potential to become a fundamental method within archaeological practice and enter the mainstream. With the help of case studies, large and small, this session intends to facilitate the liberation of archaeological survey from the margins of research and advocate its importance to an international audience. There will also be added emphasis upon international contributions for it is currently believed that this specialism is essentially a British contribution towards archaeological research. Hopefully this session will either dispel the myth or encourage its expansion outside of the UK. Whether you specialise in intrusive or non-intrusive techniques, academia or commercial archaeology, this session is intended to appeal to all. Its focus upon holistic approaches should encourage a healthy dialogue between different disciplines and specialists. Kate Page-Smith, CgMs Consulting, England Introduction to Session Interpretation at the end of the tape measure: the practice of archaeological survey and historic landscape analysis today Mark Bowden, English Heritage This paper will be introduced by a brief history of archaeological survey in Britain. It will present a view of the current state of archaeological earthwork survey and historic landscape analysis in England, illustrated by some recent case studies. It is now widely accepted in excavation that ideally interpretation happens ‘at the point of the trowel’. It will be argued here that equally in non-intrusive archaeological research, interpretation is an integral part of the fieldwork process, building a multi-period landscape history. From this stance, the paper will address some of the issues raised in the Session Abstract regarding the marginal position of survey even within its supposed homeland in the British Isles. Earthworks and other historic landscape features are often under-valued, even by archaeologists. It is necessary to demonstrate that earthworks are part of the beauty and fascination of the landscape, that they are valuable visual markers and that they are crucial to a proper archaeological understanding of landscape history. In order to do this we have to build and maintain the skills to record, analyse and understand these features. It will be suggested that these skills can be developed in the hands of independent and amateur practitioners, as well as more widely in the world of professional archaeology. The Origins of Archaeological Survey in Spain Margarita Díaz-Andreu Abstract: Until very recently most archaeologists in Spain equated archaeology with excavation. It was assumed that this partly derived from the relative isolation in which Spanish archaeology developed after the Spanish Civil War, during the Francoist regime (1936/39-1975). The study of the Pericot Archive, however, shows that this was not the case. There was an influential group of Spanish archaeologists who had regular contact with both the U.K. and the U.S.A. Despite this, Spain was unmoved by some of the developments in these countries. This paper will analyse the situation and try to explain why archaeological practice did not change much during the period under study Landscape archaeology and predictive modeling within Dutch archaeology: some trends H.M. van der Velde (Archeologisch Diensten Centrum, Netherlands) Since the beginning of the 20th century Dutch archaeology was closely connected to archaeological trends within Germany from which it derived most of the field techniques. Also the paleo-ecological background of one of the fathers of modern Dutch archaeology (Van Giffen) led to the development of a more environmental approach to the discipline. His followers (e.g. Waterbolk and Van Es) developed a kind of settlement archaeology within regional projects. In the 70’s and 80’s a lot of large scale excavations started in order to understand the development of settlements and cemeteries from a cultural and environmental point of view. The same years witnessed the birth of theoretical archaeology within this large scale excavations. From the 90’s onwards the focuses gradually changed towards the cosmological interpretation of landscape, the archaeology of the periphery and the so-called cultural biography of landscape (e.g. Roymans and Gerritsen). Some regions within the Netherlands are the most thoroughly researched landscapes of Northwestern Europe and hundred of hectares have been excavated. In fact on this very moment ADC-Archeoprojecten (the biggest commercial firm within the Netherlands) is excavating roughly 25 hectares in Boxmeer (within the time span of 9 months). Because of the way the Dutch archaeological monument act was working only a few institutions were permitted to undertake excavations. That’s why in 1986 an unemployment project (RAAP) started of as an commercial firm doing non-destructive prospective archaeology. This early start of commercial prospective archaeology together with the implementation of the Malta treaty in the mid 90’s led to a rapid development of this branch of archaeology. Not only RAAP, but nowadays every Dutch commercial firm is employing archaeologists specializing in landscape development and prospective archaeology. At the same time the Dutch state service shifted it’s focus towards cultural heritage and in it’s slip stream non-destructive archaeology. They started projects like ARCHIS which led to the development of a database comprising information about every excavation and find locations in the Netherlands. In recent years this databases have been modeled into GIS leading to archaeological value maps. The valueinterpretations are mainly based on geological maps. Still little has been undertaken to interpret and value historical landscapes using modern archaeological theories. Because of this, Dutch archaeology shows an overrepresentation of settlement areas and maps have become very static. Cemeteries and shifting choices of location are not very often highlighted. This contribution deals with some recent projects undertaken by ADC. They are an example of shifting focus towards modern predictive modeling. The first project deals with the Actual Height Measurement-maps which have been made for the Netherlands and their possibilities for landscape archaeology. The second project involves some major excavations in the Dutch province of Limburg searching for archaeological answers in the periphery of settlements. The third project is about an archaeological value map of a local town in the East of the Netherlands. Close collaboration between archaeology, paleo-ecology and historical-geography led to new models about shifting location choices. Margaret Gowen, Margaret Gowen & Co. Ltd, Ireland Title to be confirmed Tea Break The interdisciplinary cultural landscape. Søren Diinhoff The study of the relationship between man and nature is a central issue in archaeological science. That is probably due to a basic wish, to understand how human culture is established in a dialectic interaction between cultural, ecological and geophysical conditions. Still since the childhood of archaeological science back in the nineteenth century it has been an established fact that archaeology can not explain this relation by itself. The study of culture and nature is by definition an interdisciplinary project. Throughout the story of archaeological science the study of man and landscape has gone through a distinct development. In general we have gained better knowledge and though the development has not been linear, it has been promoted by a continual accumulation of knowledge through time, an establishing of scientific schools and organisations, by politically governed financial support, new theoretical thinking and development of new field and analytical methods. In recent years the archaeology of South Scandinavia has experienced cultural, political and economic attention. Several comprehensive interdisciplinary projects have been launched, all focusing on the cultural landscape. A case study – The research project “Land Use and Plant Diversity”. This article is partly based on my own experiences as a participant in the interdisciplinary research project Land Use and Plant Diversity. This is one of several large projects initiated by the Research Council of Denmark in the middle of the 1990`s. The project operates within a budget of approximately 10 million Danish kroner, with a staff of more than a dozen researchers picked from archaeology, history, genetics and botany. The project is an offshoot to the “Rio Conference” objective, to strengthen preservation and research into biological diversity. Man influences environment and this has consequences for the biological diversity of the earth. The question is how to secure a viable development. Our project is built up of several sub projects, which in an integrated corporation seeks to reveal the conditions of present botanical diversity. The research focuses on selected landscapes, influenced differently by human activity. Hence it is possible to study how botanical diversity has developed in respectively intensively and extensively exploited landscapes. It is a study of the variation of species in present physical botanical environments seen through 2500 years of cultural history. The project has chosen two Danish research areas. One area is in the western part of Zealand; the other is the district of Himmerland to the southeast of Limfjorden in Northern Jutland. We shall take a look at the latter. Himmerland covers an area of 2372 km2, and it holds 2105 Iron Age features at 1541 different sites (fig. 1). Site information has been recorded at the archives and collections of the National Museum in Copenhagen (NMI) and the two local museums in Aalborg (ÅHM) and Aars (VMÅ). To establish a meaningful link between the information of archaeological data and the overall objective of the project, it is important that some basic agreement exist between the participating researchers. Basically one must approve that: A connection existed in prehistory between human culture and the ecological and geophysical conditions of the landscape. This relation can be tested in a modern landscape and it can be mapped for analysis. Furthermore if the project is to be realistically practicable - whether it is an interdisciplinary or a multidisciplinary organisation – it is important that: Consensus exists about the overall objective. The project must be meaningful to all participants. Agreement exists to some degree about the applied scientific methods, and it is possible to compare and test the different results within the project. As an archaeologist one soon realizes how difficult it is to calibrate humanistic research into a common testable scientific language, and one may question if it in fact really is possible or even desirable. The chosen method is called landscape archaeology. The method is a combination of traditional settlement archaeology, cultural geography and Site Catchment Analysis. The analysis deals with comprehensive cultural and geophysical data, why use of digital mapping and GIS is indispensable. In many ways the method can be compared to the concept of predicative modelling (Kohler 1988). The distribution maps. The distribution maps are the main tools for analysing and presenting the archaeological finds. The question is whether the produced find maps really are representative of the prehistoric settlement pattern (assuming it actually is possible to recognize patterns in the find material). To answer the question a number of statistical analyses have been carried out. A few examples will be shown here and briefly commented. The composition of find types and year of retrieval. Archaeological finds need to be retrieved and throughout the decades of archaeological history different find types have turned up very unevenly as shown in figure 2. Depending on the year of observation, the find picture will vary and will accordingly show different settlement patterns. Museological or amateur excavations. Some find types are difficult to recognize and demand a higher professional competence while other are easier. The find picture will be influenced whether the museological readiness is built up by amateurs or by a professional trained staff. Earlier amateur excavations were frequent but in the last decades professional curators have taken over the majority (fig. 3). The composition of the museological readiness will influence the settlement pattern. Find density and the archaeological readiness. In areas nearby the two local museums and near enterprising amateurs the find density turns out to be high (fig. 4). Especially earlier the factor of distance played an important role but that is not the only explanation. Areas with a high find density seem to attract both professional and amateur archaeologists attention beyond the average readiness. Archaeological finds need to be retrieved. Finds need to be found. Normally some kind of modern activity in the landscape expose the prehistoric site before it comes to our attention. It turns out that different activities reveal different find types (fig 5). Peat cutting results in bog finds, metal detectors in trade posts and landing places etc. Different activities will produce different find distributions. Conclusion: representative analysis. The district of Himmerland probably offers one of the best Iron Age find contexts in Denmark, but still the data is insufficient and difficult. The find distribution is not directly identical to the prehistoric settlement pattern. Several conditions determine what we have knowledge about. A few of these have been presented above. The topographical analysis. Parallel to the representative analysis runs a topographical analysis. Several types of geophysical and historical maps have been produced for analysis. A few examples will be shown. Himmerland is geographic clear-cut, it is bounded by sea and fjords to the west, north and east and by waste wetlands to the south. The district fully meets the methodical demand for a geographic and cultural unit (Roberts 1996:8). Himmerland is by no mean flat, it is a varying hilly and undulated landscape traversed by rivers and wetlands. In many ways the district is a perfect object of study. A wide range of geophysical conditions have been analysed, such as the example shown in figure 6. The figure analyses the relation between soil type and settlement. This analysis and many more have shown how the Iron Age settlements are located mainly on the rim of sandy undulated hills at a near distance to water and pasture. This placing secures ample supply of cattle feed and drainable soil for grain-growing. Another type of map analysis is the use of historic maps such as the one shown in figure 7. This map is a digital reproduction of maps produced around the year 1800 by The Royal Commission of Sciences. The map presents the relationship between the historic landscape and the Iron Age settlement, thus indicating a higher likeness between the two. There is a clear tendency that the Iron Age settlements are located in the same landscapes as the historic villages and that they both tend to avoid the meagre heaths. The presumed relationship between historic and Iron Age settlement seems to be clear especially in the Late Iron Age. Concluding remarks. The main conclusion is that the landscape archaeological analysis is a useful and gives good potential for further research. There are great difficulties related to this method, even when using a find material as comprehensive as that of Himmerland. In a regional perspective, the find distribution does express cultural patterns and a relation between the settlement and the geophysical conditions of the landscape. However if one changes the scale of research from the perspective of the regional settlement pattern to a local analysis of single farms, the pattern is no longer clear and uniform. In densely populated areas some farms are located on barren soil while in adjoining areas with no or only sporadic settlement there may be plenty of vacant fertile land. The overall regional pattern does not explain the local settlements, why is that? Answer 1): The settlement is in respect to economic strategy related to the extent and quality of the surrounding area, to the soil type, the hydrographics, and to the flora and fauna of the environment. Though the geomorphology and ecology of the landscape set certain limitations - and therefore are determinant conditions – the choice of economical strategy and the location of the settlement itself is basically governed by cultural conditions. A landscape may be barren in respect to agriculture, but rich in respect to for example pastoral economy, fishing or iron production. Whether a landscape should be characterized as a marginal area all depends on the chosen economic strategy. The physical conditions of the landscape must therefore be seen through a cultural filter, put together by the cultural and political organisation of the society, the economic strategy, technology and demography. Divergences in the landscape archaeological analysis may be caused by insufficient knowledge about the means of production of the prehistoric society in question. Answer 2): The method of predicative modelling analyses the archaeological find as a single basic unit and compares it to different ecological and geophysical conditions, as if every unit existed in a closed system. Our knowledge about the Iron Age settlements however shows how settlements are connected into cultural and economic networks with some kind of central management of production. Answer 3): The human spatial organisation in the landscape is not only physically conditioned and the landscape is not only a three-dimensional container wherein finds are put to order. To the Iron Age farmer the land was more than the sum of its physical components. It was the land of the forefathers and the lineage and their history was inscribed in the myths of the landscape. The cultivated land, the graves on the hill all reminded the farmer, that this was the home of his kin. The Iron Age society was organised within a logocentric time and space perception of the landscape. The cultural landscape is not only a landscape with culture in it. It is landscapes organised in correspondence with cultural standards in a cognitive space. Landscape archaeology and predicative modelling do not really explain or understand in details the complex interaction between culture and nature regarding prehistoric settlement. It is not possible to weight the different variables being analysed. The archaeologist faces a serious problem, should the predicative model be abandoned or should one try to “supplement” it. The later solution is the better. The inductive map analysis of the predicative model ought to be followed up by explaining cultural models and deductive hypothesis in order to make the results archaeological viable (Kvamme 1992). Doing this the analysis is no longer testable “hard science” as prescribed and this could be a problem for the interdisciplinary project, where the standard of reference is a measure of success. Participation in a project is a social process in many ways. The granting authorities seek to secure that the project is practicable within time limits - the researchers seek consensus about the overall objective, and perhaps sometimes the will to success and agreement is more explicit, than what is realistic. Maybe sometimes the different results in an interdisciplinary project cannot really be compared and tested, and the only glue linking it together is the imported cultural model. We study at the same universities, we read the same books, and maybe this tends to result in a certain conformity in ways of thinking, making way for consensus where none should have been found. The social processes of participating in a research project can hinder natural discrepancies to be outspoken. At this point one may conclude that landscape archaeology and predicative modelling have gotten a foothold and are still spreading out. In short term perspective this is positive, we now have the means to test descriptive models dealing with cultural development in a regional perspective. In a long term perspective we should develop a more humanistic approach and superstructure. Literature. Kohler, Y. A. 1988: Predicative Locational Modelling: History and Current Practice. In W. J. Judge & L. Sebastian (eds): Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method and Application of Archaeological Predicative Modelling. Washington. p. 19-59. Kvamme, K. L. 1992: A Predicative Site Location Model on the High Plains: an Example with an Independent Test. Plains Anthropologist 37. p. 19-41. Roberts, B. K. 1996: Landscapes of Settlement. Prehistory to the present. Routledge. London and new York. Digging is not the only archaeology – the sometimes turbulent relationships between field survey and excavation Paul Belford, BSc. MA. MIFA Head of Archaeology and Monuments Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust In the UK more than 90% of archaeological fieldwork is undertaken in a commercial, planning-focused context. Most of this comprises excavation of one form or another, ranging from small test pits and trial holes to large open area excavations. Very little field survey is undertaken at all, and, where it is done, the motive is usually to locate the results of other work (such as geophysics or excavation) rather than to provide a landscape analysis in its own right. By far the majority of field survey is undertaken by a very small minority of publicly-funded bodies such as English Heritage, National Parks and local authorities. As a consequence, many archaeologists in the UK are unaware of the potential benefits that can accrue from close integration of field survey and intrusive fieldwork. This paper will survey several examples of research-led and commercial work to show how landscape survey has, or has not, been incorporated and into archaeological studies. These examples will focus on the medieval, post-medieval and industrial periods, which have seen an unprecedented growth in research interest and theoretical development over the last decade. Field survey has been usefully deployed in classic upland and rural environments, but urban or semi-urban landscapes have been sadly neglected. Case studies will include mining landscapes, military earthworks, industrial watercourses and picturesque landscapes of pleasure. The paper will seek to investigate ways in which landscape survey can be integrated into more difficult areas such as urban and ‘brownfield’ archaeology, with attention particularly focussed on developing field survey in the flourishing commercial sector. The relation between field survey carried out by private collectors s of the early 20th century and the archaeological field surveying of today. Johannes Carlåhs, a case study Oscar Ortman The County Museum of Bohuslän Box 403 S-451 19 Uddevalla Sweden In connection with the prospectation of a new motorway through central Bohuslän the county museum of Bohuslän and the central board of antiquities UV-Väst carried out excavations of prehistoric sites and monuments. The sites in question, located north of Uddevalla, were examined in the years 2002 and 2003. In connection with this project I have studied how the archaeological perception of the area evolved through several years of field surveys carried out by a small group of devoted amateur archaeologists. These amateur archaeologists were active between 1910´s and 1960´s. The area which was covered by their work came to be a key area in the discussion of the chronology of early Mesolithic throughout the 20th century. My case study has given me the opportunity to study how the conception of the early Mesolithic changed during the first part of the 20th century. I could also see how the relationship changed during this period between private collectors, such as Johannes Carlåhs and his brothers Oscar and Amandus Johansson, and semi-professional archaeologists, such as Johan Alin and Axel Stene. I was also able to discuss the relationship between the field surveys of the 1920´s and 1930´s on the one hand and the excavation of the same site in 2002 on the other hand. Another conclusion which can be drawn from the study is that the history of a site can be understood better, if we pay more attention to how the site has been examined throughout the years. Mapping Kalawao: Two Seasons of Intensive Survey in an Early Hawaiian Leprosarium James L. Flexner, University of California, Berkeley Many early treatises on archaeological fieldwork treat survey as a necessary first step towards the meat of any archaeological project, excavation. Initial research design for a historical archaeology project in Kalaupapa National Historical Park, Moloka'i, Hawaii reflected such a bias, despite the strong tradition of settlement pattern studies in Polynesia. Survey was intended to identify late-19th century house sites suitable for excavation. These houses are to be studied as loci where deeper cultural beliefs and social structures were created and transformed through daily practices. However, two years of surface survey in Kalawao have revealed that the surface remains in the area can tell us far more than simply where to dig. The project's developing survey methodology, which includes the creation of detailed maps of the research area’s stone architecture, helps to inform a developing theoretical emphasis on space and place. This paper will examine the value of maps created during archaeological survey as an analytical tool. This approach is especially useful given Kalawao’s history as a place of exile for inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands who were diagnosed with Hansen’s disease (commonly known as leprosy) between 1865 and 1900. Scholars have often noted the spatial manifestation of power in institutions such as leprosaria. Thus, looking to the surface in Kalawao can provide a window into the ways in which power was experienced and enacted by people living in the past.