Literary-Forms-of-Representation-2007

advertisement

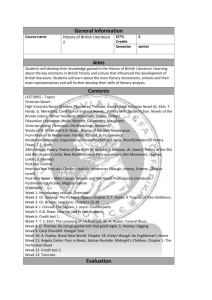

LITERARY FORMS OF REPRESENTATION HANDBOOK 2007-08 Is it possible to define ‘poetry’, ‘novel’, ‘drama’ or ‘film’? How do you decide on the ‘meaning’ of a literary, theatrical or cinematic text? What is involved in analysis and interpretation? This year long genre-based course addresses issues of this nature. It aims to acquaint you with some of the developments in the four genres and to some key critical terms. The broad aims of the course are: to encourage you to read and view closely, observantly and critically; to encourage you to think deeply about the ways the world is represented through literary and visual media; to help you to understand the relationship between form and content. You will be involved in group discussion and analysis of a selection of challenging texts, ranging from the ancient Greeks to the contemporary period, and we hope that you will be stimulated to share your own new and unique responses to these texts with us and with your fellow students. Organisation Each week there will be an hour-long lecture starting at 9.00 on a Tuesday morning, attended by all students on the course. This will be followed by seminars for which you will be split up into groups. These seminars also last an hour and will start at 10.00, 11.00 and 12.00. In term one the focus will be on poetry and prose narrative. In term two we will turn to drama and film. In the last four weeks, the course will culminate with an examination of how poets, novelists, playwrights and film-makers have represented London. Video and film extracts will be included, and visits to the theatre will be arranged. Texts for term one Poetry: The poetry we will study appears in this handbook. Short story: Three short stories also appear in this handbook. Novel: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens (Penguin) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (Vintage) Texts for terms two and three Drama: Oedipus the King in The Three Theban Plays by Sophocles trans. Robert Fagles (Penguin) A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (Cambridge or other accessible edition) An Ideal Husband by Oscar Wilde (Nick Hern) Film: Run Lola Run (Dir. Tom Tykwer) London material: A selection of poetry which appears in this handbook; Harold Pinter’s play The Caretaker (Faber); Monica Ali’s novel Brick Lane (Black Swan); and the film Dirty Pretty Things (dir. Stephen Frears). Lecture/Seminar Programme: Term One Block One: Poetry Week 1 (October 2nd): A showing of an abridged version of the film Il Postino Aims: To introduce the course and poetry Seminar: Discussion about poetry and what the film says about poetry and poets Week 2 (October 9th): Poetry 1: Methods and Techniques of Analysis Aims: To introduce some characteristics of poetry e.g. rhythm, syntax, metaphor etc. Seminar texts: Selected Poems (in handbook) Week 3 (October 16th): Poetry 2: Genres and Styles of Poetry Aims: To compare forms: e.g. sonnet, ballad, free verse Seminar texts: Selected Poems (in handbook) Week 4 (October 23rd): Poetry and Identity Aims: To consider the cumulative effect of a volume of related poems Seminar text: Excerpts from Grace Nichols, The Fat Black Women’s Poems (in handbook) Week 5 (October 30th): Political Poetry Aims: To consider how poetry can be political, and what kind of intervention it can make Seminar text: Tony Harrison, V (in handbook) Week 6 (November 6th): Tutorial week There will be no lecture or seminar this week. Block Two: Prose Narrative Week 7 (November 13th): The Short Story Aims: To introduce the form, and explore some different types of short story Seminar Texts: Selected Short Stories (in handbook) Week 8 (November 20th): The Novel 1 Aims: To introduce the novel: genre and realism, bildungsroman, narrative conventions Seminar text: Charles Dickens, Great Expectations Week 9 (November 27th): The Novel 2 Aims: Considering how to read form and content; different contexts Seminar text: Charles Dickens, Great Expectations Week 10 (December 4th): The Novel 3 Aims: Introduction to the Modernist novel; the implications for the novel form Seminar text: William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying Week 11 (December 11th): The Novel 4 Aims: To investigate realistic and non-realistic representation; subjectivity and objectivity Seminar text: William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying Lecture/Seminar Programme: TermTwo Block Three: Drama Week 1 (January 8th): Drama 1 Aims: To introduce the Classical play: theatrical context; audience; actors; masks Seminar text: Sophocles, Oedipus The King Week 2 (January 15th): Drama 2 Aims: To introduce dramatic conventions: characters, structure, action, language Seminar text: Sophocles, Oedipus The King Week 3 (January 22nd): Drama 3 Aims: To introduce Shakespeare: context, conventions, language; love and the irrational Seminar text: William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream Week 4 (January 29th): Drama 4 Aims: To explore the significance of the play-within-a-play Seminar text: William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream Week 5 (February 5th): Drama 5 Aims: To introduce the social drama of the modern age Seminar text: Oscar Wilde, An Ideal Husband Week 6 (February 12th): Tutorial week There will be no lecture or seminar this week. Block 4: Film Week 7 (February 19th): Film 1 Aims: Reading film language Seminar: New ways of looking at and thinking about film Week 8 (February 26th): Film 2 Aims: To introduce Run Lola Run Seminar Text: Tom Tykwer (dir.), Run Lola Run Block Five: London as represented in different forms Week 9 (March 4th): London in Poetry Aims: To introduce different poetic treatments of London and the Romantics’ view of the city Seminar texts: Selected Poems on London (in this handbook) Week 10 (March 11th): London in Drama Aims: To consider what role London plays as the setting of stage drama Seminar text: Harold Pinter, The Caretaker Lecture/Seminar Programme: TermThree Block Five: London as represented in different forms (continued) Week 1 (April 8th): London in the Novel Aims: To introduce postcolonial London Seminar text: Monica Ali, Brick Lane Week 2 (April 15th): London in Film Aims: To explore how London can be presented through film Seminar text: Stephen Frears (dir.), Dirty Pretty Things Block Six: Revision and Assessment Week 3 (April 22nd): Revision Lecture Aims: To prepare students for the LFR exam Seminar texts: All the texts covered in terms 2 and 3 Week 4 (April 29th): Revision There will be no lecture this week, though revision sessions may be held within seminar groups if there is a demand for them Weeks 5-7 (May 6th – May 23rd): Assessment period The LFR exam will take place during these three weeks, the date to be confirmed. LITERARY FORMS OF REPRESENTATION ASSESSMENT Terms One, Two and Three Assessment is in five parts over the whole year with weighting as follows: Term One Poetry Analysis (1000 words) 12.5% (Deadline: November 13th) Essay (novel) (2000 words) 25% (Deadline: January 8th) Term Two Drama/Film Analysis or Presentation (1000 words) 12.5% (Deadline for analysis: February 26th; deadline for presentation: the day your subject is discussed in seminar) Term Three Essay (London) (2000 words) 25% (Deadline: April 22nd) Exam 25% (Between May 6th and May 23rd) Additional non-assessed coursework As preparation for the assessment and as part of the course please hand in to your seminar tutor: (a) On October 9th an original poem, on any theme and of any length. (b) On February 19th the first page of an additional scene created by you for An Ideal Husband. Provide stage directions as well as dialogue. Use Wilde’s own practice in his play as a guide. ASSESSMENT DETAILS for Term One Poetry Analysis Choose ONE of the short poems in the handbook OR a four-verse extract from V and write a 1000 word analysis of it, using the guidelines in this handbook. You should illustrate your points through quotation from the poem; there are guidelines on how to quote poetry in this handbook. Do NOT refer to secondary sources, particularly those found on the internet. Essay (novel) Write an essay of 2000 words about EITHER Great Expectations OR As I Lay Dying in response to one of the topics given overleaf. Your essay should refer to specific incidents and passages from your chosen novel (giving a page reference for each quotation) but you should NOT refer to secondary sources, particularly those found on the internet. Topics for essay (novel): 1. Discuss the way either of the two novels you have studied experiment with narrative. 2. ‘Women in 19th century and early 20th century fiction are invariably represented as subordinate to men’. Critically examine the representation and role of women in one of the two novels studied in the light of this assertion. 3. Discuss the treatment of ‘the journey’ in one of the two novels studied. What kinds of journeys do the characters make and what kind of a journey does the reader make through the book? 4. ‘Families are a source of unity and strength.’ Examine the representation of the family in either of the two novels studied with this view in mind. How far is the quotation confirmed? 5. What does the novel reveal about social attitudes and assumptions at the time in which either of the two novels you have studied was written? 6. ‘Great Expectations is a novel about the connection between wealth and crime rather than a novel about the power of love.’ Discuss Great Expectations with this view in mind. 7. What is the significance of place and environment in As I Lay Dying? NB It is important that you refer to the guidelines on essay writing and coursework presentation that appear in the English and Performance Studies Handbook and discuss with your tutor or seminar leader any queries you have about essay writing and essay presentation ASSESSMENT DETAILS for Term Two Drama/Film Analysis or Presentation EITHER Offer an oral presentation in class lasting 12-15 minutes on a topic relating to either Oedipus the King, A Midsummer Night’s Dream or An Ideal Husband. Consult the guidelines and the list of suggested topics that appear in this handbook. Presentations will be scheduled at the beginning of the term by your seminar leader. OR Choose a significant moment in ONE of the plays studied OR in Run Lola Run. Write a 1000 word analysis of two – three pages of text if you have chosen a play, and no more than five minutes of screen time if you have chosen the film. Remember to explain what your chosen excerpt is and place it in the context in which it appears in the text as a whole; it us also important that you consult the guidelines on drama and film analysis that appear in this handbook. If you are analysing drama, you should illustrate your points through quotation from the play; there are guidelines on how to quote dramatic dialogue in this handbook. If you are writing about a play, please include a copy of your chosen section with the submitted coursework. ASSESSMENT DETAILS for term three Essay (London) Write a 2000 word essay on the following topic. When choosing the texts that you wish to compare you should bear in mind that you will need to write about at least one London text in your exam, and that you cannot write about the same text in two different assessments. 1. Compare and contrast the way London is represented or used in two texts. NB It is important that you refer to the guidelines on essay writing and coursework presentation that appear in the English and Performance Studies Handbook and discuss with your tutor or seminar leader any queries you have about essay writing and essay presentation Exam The exam will last two hours and you will be required to answer two questions, both on work covered in terms two and three. Part One will offer a choice of questions on texts studied in the Drama and Film blocks. You will answer ONE question from this part. Part Two will offer a choice of questions on texts studied in the London block. You will answer ONE question from this part. You will answer TWO questions altogether. Please note that you may not use material already used for your analyses, presentation or essays. A copy of last year’s exam paper is included at the back of the printed version of this handbook. Poetry Analysis: some guidelines In poetry, the way in which something is said is as important as what is being said. The best advice to give you about analysing poetry is: read the poem. Read it again. Read it out loud. Put it down and do something else for a while. Then read it again. Poems are not designed to give up their meaning straight away; they are designed to be pondered, savoured, returned to. Meanings reveal themselves in poetry through repeated reading and careful thought. When you analyse a poem you should pay attention to all of the following, though you may not find something worth noting about each and every point listed here. 1. 2. The poem’s form and structure (a) Describe the use of rhyme, sound patterns, rhythm, the poem’s shape and appearance on the page. (b) Look at the relation between a pause or sentence break and the ends of lines and stanzas. Do they coincide? If the poem does not have a set rhyme scheme or meter (i.e. if it is ‘free verse’) ask yourself why each line is the length that it is. It will help you to identify a poem’s rhythms to read it out loud, and you might also consider counting the syllables in each line to see if a regular pattern is being followed. (c) What do you think is the relationship between the sound and rhythm of the poem and what the poem is saying? Do the sound and rhythm work to strengthen the poem’s message and, if so, in what way? Could it be that the sound and rhythm of the poem work to cast doubt on what is being said? The poem’s language (a) Identify and comment upon key phrases and statements. Are they ambiguous? Note and try to account for any unusual or obscure uses of language. (b) Be aware of the language that is factual and descriptive and the language that is figurative, where the poet has used simile, metaphor or imagery. What light does the figurative language used shed upon what is being described? (c) Is the language of the poem intended to remind us of other uses of language? What kind of a tone does the language of the poem convey, and can we infer anything about the personality, status or mood of the person who might be speaking? Is this a personal or a representative voice? Who might the poem be addressed to? 3. Does the poem have an ‘argument’, i.e. is there a point being made?What would you say that point is? How is the point emphasised or brought into question by the way in which it has been expressed in poetry? 4. Think about your experience of reading the poem. What was clear to you straight away, and what took time to become evident? Are there aspects of the poem that remain a mystery to you? Might this be deliberate? How to Quote Poetry Remember that in poetry the arrangement of the lines is important. Don’t set the poem out as prose. There are two ways to quote poetry. If you just want to quote a couple of lines, or individual words, do it as follows: The opening of ‘Make-Up’ is initially confusing: ‘ran cranberry over logan/Japanese ginger orchid’. There is no punctuation and the words do not seem to make sense. The verbs ‘ran’, ‘stacked’, ‘mixed’ in the poem suggest an order. Notice: The title of the poem is placed in inverted commas The quote is placed in quotation marks, and individual words from different parts of the poem are placed in separate quotation marks A dash (/) is used to show where one line of the text ends and another begins The sentence of which the quote is a part makes grammatical sense The poem’s words, spelling and punctuation appear exactly as in the original If the quotation exceeds a couple of lines set it out as follows: The opening of ‘Make-Up’ is initially confusing: ran cranberry over logan Japanese ginger orchid spice glow mandarines frost light clearly There is no punctuation and the words do not seem to make sense. Notice: A space is left before and after the quote The quote is indented (meaning that there is a wider margin on the left-hand side of the page for the duration of the quote) Quotation marks are not used The poem’s words, spelling, punctuation and layout on the page appear exactly as they are in the original Giving a presentation: some guidelines and suggested topics We encourage students to give presentations in class because it gives valuable experience of addressing a group in a relatively informal situation. The aim is not so much to convey information as to set out some areas for further discussion. A good presentation is lively, engaging and stimulating, and you are encouraged to put something of your own personality into it. Some quick guidelines Although we expect you to know roughly what you are going to say in advance, we don’t encourage you to read from a prepared script – that can be rather dull to listen to. Work from notes, but remember that you are talking to the group; explain your ideas in your own words and maybe throw in a joke or two. Make sure you have about the right amount of material; some students prepare far too much and can’t squeeze it all in, while others don’t have enough to say and end up trying to pad it out. Have a practice at home and time yourself. If you can use visual aids such as OHP slides, Powerpoint or handouts that will help you to get your points across more clearly and make the structure of your talk more easy to follow. It will also give your audience something to look at other than you! Suggested topics for presentations For Oedipus the King a) How does Oedipus learn the truth about himself? b) Consider the roles of Creon, Tiresias and Jocasta in relation to the play’s themes and to Oedipus. How does each character express him or herself and what is the natuire of the conflicts that arise? c) Comment on the various functions of the Chorus. What does theior presence add to the drama? For A Midsummer Night’s Dream a) What is the significance of the play’s title? How are we made conscious of ‘dream’ elements? b) Discuss different attitudes to love and power that are expressed in the play. c) What is the relationship between the human world and the supernatural world in the play? d) What is the function of the play-within-a-play? e) Select one character and consider his or her function in relation to the play’s action and themes. For An Ideal Husband a) What is the relationship between money, status and morality as presented in the play? b) Is Lady Chiltern wrong to blame her husband? c) Consider either Lord Goring or Mrs Cheveley as an outsider figure. What sets them apart from the society of the play, and how does that change the way we respond to them? d) What is the relationship between humour and seriousness in the play? Drama Analysis: some guidelines All the different elements of drama – the visual as well as the verbal – contribute to the play’s meaning. Some of these elements are there for you to see on the page; others you need to imagine in performance on the stage. Stage directions tell you how the play is intended to look and sound, but bear in mind that different directors and actors will present the same play in different ways. This is called interpretation of the text. When analysing drama you should pay attention to all of the following, though you may not find something worth noting about each and every point listed here. 1. Stage directions Stage directions are instructions to the production team. They appear in italics and are concerned with the action, set, lighting, costume, sound effects, music, tone of voice etc. In Greek and Shakespearean drama the stage directions have been added later by editors of the text to make it easier to follow; writring materials were in short supply when Sophocles and Shakespeare were working and the playwright would have been on hand to explain what needed to happen when. Even when there are no stage directions for a given passage, remember that all the time the audience is being presented with a visual spectacle. Think about what is happening, how it might look, what impact the visual or aural aspects of the play might have, and how that changes the way in which the play’s themes will be understood. 2. Characterisation Different dramatists writing at different times have had different ideas of what ‘character’ might mean. ‘Psychological realism’ is a phrase that would have meant nothing to Sophocles or Shakespeare and little to Wilde. Nonetheless, each playwright has created characters with their own consistent personalities, and which may develop as the events of the play proceed. Ask yourself how a character is established, how he or she speaks, appears and acts. What status does a character have in the society depicted and how important is he or she to the story being told? What sort of a person is this? What might have made them that way? Do they remain the same throughout or do they change? 3. Language Remember that dramatic language is written to be spoken, so think about what it might sound like to an audience. What is the suggested tone, what is the rhythm of what is being said? Is there humour, irony, emotion of some kind? If there are pauses, think about why they are there and what might be happening during them. 4. Structure or dramatic shape Think about how the play is put together. Does one thing follow on from another, or are the audience asked to make the connections themselves? Is the play divided into Acts or scenes? Is there a satisfying climax? How to quote dramatic dialogue in poetry and prose All three of the drama texts studied on this course make use of poetic verse, and the Shakespeare and Churchill plays also incorporate passages of prose. It is important that quotations from the plays are set out correctly on the page, and this section shows you how to do that. The best advice is to copy the original exactly in terms of spelling, punctuation and grammar. The editions used below are: Sophocles, The Three Theban Plays, trans. Robert Fagles (Penguin); Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Cambridge School Shakespeare); and Churchill, Plays One (Methuen). The edition of the text you use should always appear in your Bibiography. Here is how to quote a long speech by a single character: Tiresias’ final words are full of defiance. At this crucial point in Oedipus the King he announces in clear terms once again that the murderer of Laius is in Thebes: I will go, once I have said what I came here to say. I will never shrink from the anger in your eyes – you can’t destroy me. Listen to me closely: the man you’ve sought so long, proclaiming, cursing up and down, the murderer of Laius – he is here. (p. 185) As Oedipus enters the palace, Tiresias proclaims that it is the king who is the killer. Notice: You introduce the quotation with a colon (:) You leave a space before and after the quotation You indent the whole quotation (which means that there is a wider margin on the lefthand side of the page for the duration of the quotation) and set it out as poetry exactly as it appears in the text, with the correct punctuation used in your edition You start a new line where a new line is started in the original text, thus preserving the rhythm of the verse; usually each new line of poetic dialogue is begun with a capital letter, although that is not the case in this instance You give a page reference (Make sure that your Bibliography gives the edition of the play you are using, otherwise the page reference won’t make sense) If you are referring to the title of the play you use italics - Oedipus; if you are referring to the central character you DON’T use italics – Oedipus. If you want to include dialogue (two or more characters speaking) you should set it out as the following example shows you. Shakespeare shows the pressure that is exerted upon Hermia in Act One to marry a man she does not love. Although the situation for the characters is serious and intense, the moment could be treated as humorous: DEMETRIUS: LYSANDER: Relent, sweet Hermia; and Lysander, yield Thy crazed title to my certain right. You have her father’s love, Demetius; Let me have Hermia’s – do you marry him. (p. 9) At this point Egeus intervenes and makes clear the power he possesses as father. Notice: You introduce the quotation with a colon (:) You leave a space before and after the whole quotation You indent the whole quotation You include the names of the characters who are speaking using capitals, followed by a colon You begin each line with a capital letter You reproduce the punctuation of the original exactly You give a page reference (the edition you are using will be in the Bibliography) If you want to quote a line or a few words you integrate them into your own writing: The opening scene of Cloud Nine, which makes use initially of rhyming couplets, is dominated by Clive. Clive introduces his black servant Joshua, who is to be played by a white man, as a ‘boy’ and ‘fellow.’ Joshua reveals how he has internalised white values and attitudes when he says: ‘My skin is black but oh my soul is white./ I hate my tribe. My master is my light’ (p. 251). Notice: You use quotation marks. (N.B. You DON’T use quotation marks for the longer, indented quotations illustrated above) You give a page reference (making sure the edition used is in your Bibliography) You ensure that the sentence that includes the quotation makes grammatical sense Where poetry is quoted but not indented, the line breaks in the original are marked by a forward slash (/) If you are quoting prose you follow the guidelines as outlined for poetic drama, but you do not begin each line of a long speech with a capital letter as you normally would with poetry. The following should help you, and also illustrates how stage directions should be quoted: Clive’s sexist preference for men over women leads to a crucial misunderstanding between him and Harry: CLIVE: CLIVE: HARRY: CLIVE: HARRY: Think of the comradeship of men, Harry, sharing adventures, sharing danger, risking their lives together. [HARRY takes hold of CLIVE.] What are you doing? Well, you said – I said what? Between men. [CLIVE is speechless.] (p. 282) Clive is aghast that his sexist heterosexuality could be confused for a moment with homosexuality. Notice: You introduce the quotation with a colon (:) You leave a space before and after the whole quotation You indent the whole quotation You include the names of the characters who are speaking using capitals, followed by a colon You include any stage directions that appear, placing them in italics You reproduce the punctuation exactly New sentences but not new lines begin with a capital letter, unlike the poetic passages in Shakespeare and Churchill You give a page reference (the edition you are using will be in the Bibliography) Remember that the most important thing is always to quote the text exactly as it appears in your edition, and always to provide a page reference. Run Lola Run Directed by Tom Tykwer (1998) When you are engaging in film analysis, you need to become a different kind of spectator: you need to watch more closely and try to remain more detached than when you are simply enjoying a film. When you watch Run Lola Run it might help to focus your analysis if you can try to answer the following questions. 1. Note points in the film where the narrative shifts in the way you’d notice a new verse in a poem, a new chapter in a novel or a new scene in a play. When you’ve seen the whole film, try to think about its form, the way it’s structured. Do the events flow in a linear way? Does it challenge the expectations a viewer would normally have of a film? Can you desdribe the genre of the film? 2. Note examples of the film’s mise-en-scène. How does the film situate its narrative and characters in terms of the physical world shown on screen? 3. Note examples of unusual shots – close-ups, for instance – and any moments when the placing or movement of the camera takes on a narrative function. 4. Note examples of significant editing. How does the editing effect the pace of a given sequence? Are more than one aspect of the plot juxtaposed through an unexpected cut from one to the other? Are there moments when more than one plot strand appears on screen at a given time? 5. Listen to what’s going on too: what use does the film make of diegetic and nondiegetic sound? What does the sound add to the viewer’s experience at particular moments? Dirty Pretty Things Directed by Stephen Frears (2002) This film, set in London, is about two illegal migrants who are struggling to make a life for themselves. As you watch the film, try to jot down your responses to the questions given below. 1. This is a London of many cultures. How does the film show the interaction of different cultures? Does it show a clash of cultures? 2. This is a London where everything is for sale – including body parts. Inb what ways does the film show exploitation of the body? Is this connected to other kinds of exploitation? 3. The film centres on characters who don’t officially exist. How does the film make ‘invisible’ people visible? 4. The characters can be said to exist in a kind of underworld. How does the film develop this idea (you might want to think back to U.A. Fanthorpe’s ‘Rising Damp’)? 5. How are your reactions to what you see on screen shaped by different uses of film technique? 6. What do you think the film is trying to tell us about contemporary London?